Mapping small wetlands in Worcestershire

- 24th July 2013

Worcestershire is probably not an area that you would associate with important wetland archaeology. The Sweet Track, a Neolithic timber trackway preserved in a Somerset bog, or the Bronze Age settlement of Flag Fen found in the Cambridgeshire fens are more likely to strike a chord. These sites are both found in areas of extensive wetland, something not evident in Worcestershire. What we do have, however, is a myriad of small discrete wetland sites, in which valuable archaeological and landscape information can be found. They include cultural features such as fishponds, moats, and osiers but also natural features such as marshes, reed swamps, ponds of no known specific use, relict river channels, pronounced river meander loops and cut-off meanders.

Harvington fishponds

Though small and discrete, they are often at far more threat than the largely better documented and protected large expanses of blanket peats in England, yet contain unique and important evidence. Using these sites we can potentially research into our past environment by analysing waterlain deposits which are often organic. We can look at pollen, plant remains, any wet artefacts like leather, timber structures and even the sediments themselves. Though small, these wetlands are localised and increasingly highly vulnerable to destruction by housing and business development, quarrying, water extraction, flood mitigation measures, climate change and sometimes wetland restoration.

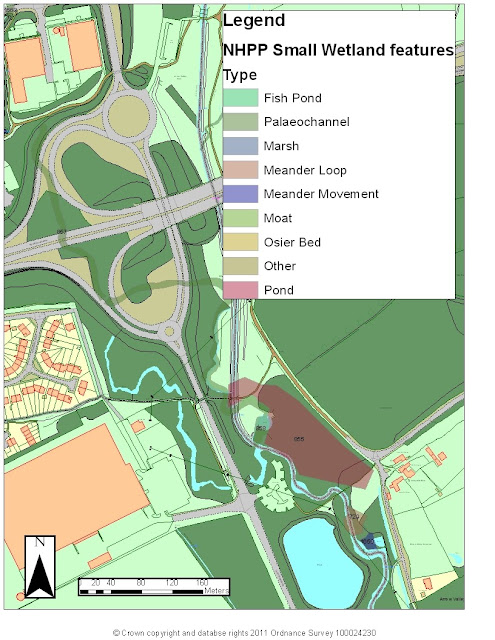

Worcestershire Archaeology has recently finished a project which set out to refine a method of mapping and assessing the archaeological potential of small wetlands in Worcestershire using a digital mapping toolkit. The work was funded through the English Heritage National Heritage Protection Programme (or NHPP) and was also greatly helped by a group of volunteers who carried out ground-truthing survey work.

The aim was to raise the profile of these sites as archaeological or historic environment assets. We can rapidly map them using a Geographic Information System (GIS) and assess them in a way that integrates the information into our Historic Environment Record (HER). You can find the HER on the 2nd floor of The Hive.

An essential part of the project has been the ground-truthing of sites using volunteer help. Our volunteer team are our ‘feet on the ground’ who photograph and take basic notes on sites that we have seen on our digital maps. Sometimes it is difficult to visualise what these sites look like (from our viewpoint in the office), and whether our assessment of these as ‘high, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ archaeological potential is correct.

We are mapping sites which are at least 100 years old and are shown on 1st edition Ordnance Survey maps. We can create a map like this on modern maps.

Arrow Valley Country Park, Redditch

We look at their size and how much they have been affected by more recent woodland cover, development (buildings and hard surfaces) or changes in standing water.

Aerial photographs and LiDAR (a remote sensing technique) can help us, but, in addition, having someone visit the site can give us a good idea of how well our desk-based methods work. This is a relatively large osier bed (willow plantation) east of Lower Astley Wood. It looks completely densely covered by woodland on an aerial photograph but viewed from a bridleway is much more open and marshy on the ground.

Aerial photograph of the osier east of Lower Astley Wood

Osier east of Lower Astley Wood as viewed from a bridleway

Osier beds (managed willow stands producing willow for basketware, wattle fencing etc) are very common in Worcestershire and some cover large areas of land. Although many were established in the 19th century, they are likely to be sited on previously marshy ground, and we can see from LiDAR images that some overlie old silted up river channels. Beneath the tree roots could be well preserved pollen sequences that record hundreds of years of landscape change, charting the felling of woodland for early prehistoric settlements and arable fields over time, and conversely renewal of woodland when settlements dwindled and passed out of use.

We can find waterlogged timber lining old river channels or relating to mill structures, or waterlogged artefacts in moats and ponds. At Bordesley Abbey near Redditch, waterlogged wooden cogs, pegs, wedges were found from excavations of the mill race, and from the bypass channel, weaving apparatus – a ‘heddle horse’, winding peg and warping paddle.

As well as providing a sink for plant debris that is essentially a record of past landscape, these structures and sometimes medieval domestic rubbish, can also survive remarkably well. Making sure we have these small wetlands on our Historic Environment Record and improving our knowledge about their potential is an important task.

Waterlogged wood from Bordesley Abbey. Image supplied courtesy of the Council for British Archaeology Research Report 92.

A summary of our findings will be forthcoming on this blog soon.

?