Mystery locked volume in Lyttelton collection

- 13th June 2014

During the process of sorting and arranging the Lyttelton collection, one of the boxes was found to contain a locked volume. There was nothing on it to indicate what it was and there was no key anywhere in the boxes. It was referred to as a ‘locked volume’ in the original list which accompanied the collection so had therefore been locked for some time. This made it slightly intriguing and we pondered what it contained and how long it had been locked.

The locked volume

Our general assistant Alan was able to gently prize the lock apart without damaging it or the volume, so the mystery volume was finally open after who knows many years. We were pleased to see it wasn’t just a blank volume after all the effort of getting it open. A quick skim through revealed that it appeared to be what is known as a ‘commonplace book’.

What is a commonplace book?

A ‘commonplace book’ is not a diary or a journal. It is a kind of ‘scrapbook’ of all sorts of information such as favourite recipes, quotes, poems, proverbs, prayers, facts, ideas which form your own personal anthology. They were often used by scholars and writers as an aide memoire or reference book. Each book was unique to the interests of the author as it combined different pieces of information in an original way. They can therefore can offer an insight into the tastes and interests of the person who compiled it. They were popular with thinkers and writers from the Renaissance onwards and some universities used them as a study aid. John Milton, Thomas Jefferson, Virginia Woolf and Mark Twain all used commonplace books.

Why keep one?

You can write down ideas as occur to you. You can write down passages from books, poems etc which you are particularly interested in or like and want to be able to find again quickly. You can record quotes you want to remember and add your own thoughts and comments. Because you are writing things out again you are more likely to remember them and it gives you time to reflect on what you’ve read – hence the use as a study aid referred to earlier. Jonathan Swift says of commonplace books in ‘A Letter of Advice to a Young Poet’ (1721):

‘A commonplace book is what a provident poet cannot subsist without, for this proverbial reason, that “great wits have short memories:” and whereas, on the other hand, poets, being liars by profession, ought to have good memories; to reconcile these, a book of this sort, is in the nature of a supplemental memory, or a record of what occurs remarkable in every day’s reading or conversation. There you enter not only your own original thoughts, (which, a hundred to one, are few and insignificant) but such of other men as you think fit to make your own, by entering them there. For, take this for a rule, when an author is in your books, you have the same demand upon him for his wit, as a merchant has for your money, when you are in his.’

So what’s in this commonplace book?

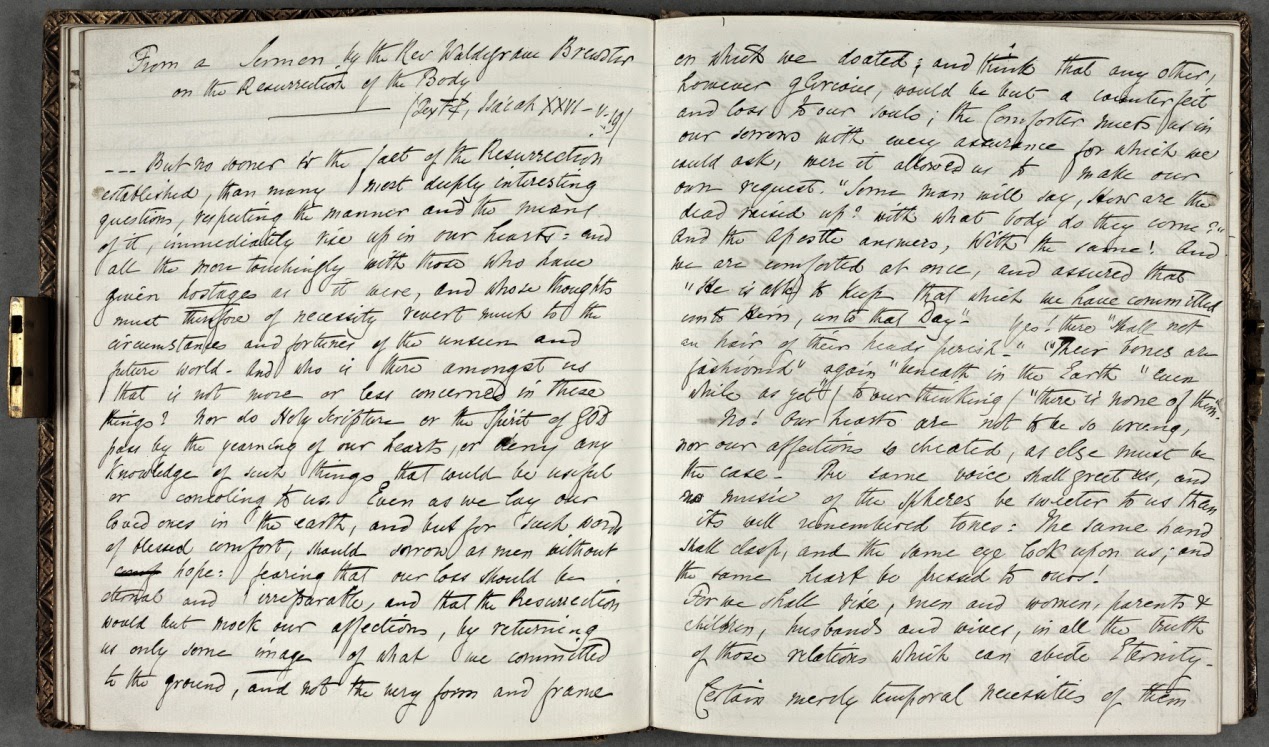

The volume contains a variety of items, some just a few lines long, others several pages. Many of the items recorded are of a religious nature such as extracts from sermons like this one.

Part of a sermon by the Rev Waldgrave Brewster on the Resurrection of the Body

There are passages from letters such as ‘Letter to a godchild’, quotes from books of the day such as ‘the Diaries of a Lady of Quality’ and inscriptions from buildings or monuments the compiler has encountered such as a German inscription from a Swiss chalet. There are also several poems such ‘The Freed Bird’ (1870) and ‘Westminster Abbey’ (1892) and a variety of hymns like the one below:

‘God is here in all my gladness’ by Rev J H Thomas

Who did it belong to?

At the moment we don’t know who it belonged to. There is nothing in the volume to indicate ownership and there are different styles of handwriting within the volume so we can’t attribute it to one particular family member. The earliest entry that’s dated is 1849 and the latest seems to be 1892, so it had been kept for just over 40 years. It’s possible therefore that it could have been kept by one person throughout their life, but equally other people may have picked up the volume and used it to record information themselves. Further research may reveal more about the compiler.

There are lots of websites about commonplace books, including advice on starting your own modern version:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commonplace_book

http://www.artandpopularculture.com/Commonplace_book

http://selfmadescholar.com/b/2009/05/15/project-start-a-commonplace-book