Monthly Mystery: Droitwich Buried Room

- 7th June 2016

The hammer pounded down once again bringing about a satisfying crack as more of the debris collapsed into the hole. “Stand back” someone called over the crowd, maybe with fear for their safety or just a hope for a better view. With a last final hit a large piece of the floor fell away leaving a hole big enough for two to fit through side by side. The group of men slowly crept forward, precariously testing their footing as they strained to peer in. At first the darkness in the hole defeated their purpose, but slowly the light from outside crept in casting an eerie gloom into the space, the air thick with dust. The light began to pick out the edges of a large room, rather than an endless void, a room forgotten by time and the depths of history. And as the floor of the room slowly revealed itself, fantastic colours and shapes melded together into the pattern of beautiful mosaics…

An opening page from a novel this might seem, yet this is something like what the scene must have been like when, at some time during the second half of the twentieth century, workers discovered a buried room beneath W. A. Lloyds (Alloys) factory which later became Wilco and then Baxenden Chemicals of Union Lane, Droitwich.

It had started as a routine installation of new machinery required by the factory for their production of ladders, but when workers broke the ground to install the new machinery they discovered a void which revealed itself as a room with mosaic tiled floors and painted walls. The factory was faced with a dilemma; if they shared this wonderful discovery with the town or alerted the archaeologists to its existence, it would be likely that the installation of the new machinery would be delayed which could severely impact on their ability to operate. And so with some regret the decision was taken to fill the room with sand and cap it with concrete slabs. Factory workers were sworn to secrecy and the room was lost to history….almost.

Over the years since, rumours of the secret room have slowly sifted through to the archaeologists and the Historic Environment Record, and on one recent occasion, one of those few present at the discovery broke their silence in the worry that the secret may soon be lost forever.

But what could the buried room with tiled mosaic floor actually be? The first possible answer that has been suggested is that the factory workers were lucky enough to have discovered a room dating to the Romano-British period, buried beneath the factory. If you are familiar with Droitwich’s past you will know this is not a far stretch of the imagination. The town of Droitwich first began to develop during the Iron Age period when its rich salt springs were first exploited on an industrial scale. Large clay lined tanks dating to this period have been discovered in Droitwich (WSM31603), and it is known that salt extraction went on in this manner (through the draining of Brine to produce salt crystals) at places like the Old Bowling Green, up until at least the 2nd Century CE (Woodiwiss, 1992). Evidence for Roman industrial activity continues throughout Droitwich well into the 4th Century CE and the Historic Environment Record contains numerous records for this period including roads (WSM30583), settlement (WSM45211), an inhumation cemetery north of Vines Lane (WSM38247), and the spectacular Villa complex at Bays Meadow (WSM00678).

Bays Meadow Villa lies less than 1km to the north of the buried room site on Union Lane. The villa was first discovered in 1849 and excavated in the 1920s, 50s and 60s. The complex has several buildings as well as a ditched rampart and associated field systems. During the 2nd century BC the main buildings consisted of two winged corridor style buildings, one of which had 18 rooms, a hypocaust system, a possible bath house and evidence for a number of high status imported pieces of furniture and jewellery. One of the spectacular finds at the villa was the remains of two fine tesserea mosaics, now held by Worcester Museum and Art Gallery. One of the mosaics was discovered by Jabez Allies in 1847 during railway construction and was made of white, red and blue tesserae with a knot at its centre. The second mosaic was expected to have filled a room 3 meters by 3 meters and consisted of a sixteen-pointed star in 6 colours. (Fox, 2011) This impressive feat of craftsmanship alongside the other recorded archaeological deposits demonstrated to archaeologists that the villa at Bays Meadow was a high status Roman building; its occupants probably made wealthy by the local salt trade. (Hurst, 2006)

(Left; Section of Bays Meadow Villa Mosaic discovered in 1920 by Hodgkinson. Photography Copyright. Worcester Museum and Art Gallery. Right: Reconstruction of the same mosaic from Hurst, 2006).

Could the workers at W. A. Lloyds (Alloys) have discovered another Roman Mosaic still intact in its original room, protected over centuries by a cap of earth?

Could we have a second villa site in Droitwich prospering from the salt trade, or another high status building or even a buried temple hidden beneath the ground like the secret temple of Mithraeum found 45 feet below the Circus Maximus in Rome? (Ruggeri, 2011)

Just the possibility of this is fascinating; however the closest excavation to the site (just to the north of Union Lane) performed in 2001 only recorded Roman pottery sherds as residual finds in later deposits so there is currently little evidence to support strong Roman activity on this site. Nevertheless this is not evidence of absence and we must not yet discount the theory.

However, a buried Roman room is not the only possibility for the site. The 1839 Tithe Map of the Parish of St Nicholas shows that the field to the north of Union Lane was known as The Friars.

(1839 – Transcription of tithe map for the parish of St Nicholas in Droitwich by David Guyatt © D. Guyatt. Parcel 119 is named “The Friars”, Union Lane runs through the centre of the map.)

(1839 – Transcription of tithe map for the parish of St Nicholas in Droitwich by David Guyatt © D. Guyatt. Parcel 119 is named “The Friars”, Union Lane runs through the centre of the map.)

The Augustinian Priory of Droitwich (WSM00683) was founded in 1331 by Thomas Alleyn of Wyche with a grant of three hundred square feet, followed by numerous further grants to extend this land and further develop the buildings. No extant building survives but we know that in the 1530s the Bishop of Dover visited the site and wrote to Cromwell expressing the state of the holdings suggesting they were of poor condition but listing farm and buildings, orchard, three tenements with gardens and more than 6 acres of closes and meadow currently rented out to tenant farmers. The friary building is known to have been located in what is now Vines Park. (Willis-Bund,1971)

Could a second priory building have been located on the union lane site containing a mosaic tile floor like that found in a number of Augustinian Priory’s across the country (for example Norton Priory in Cheshire; Greene, 1989)?

Again we are faced with little archaeological evidence to support the possibility. To the north of Union Lane the same excavation performed in 2001 discovered fishponds that were thought to belong to the priory but we have little else to go on and documentary evidence is not known to mention any established priory buildings on the site.

So where does that leave us? The 1839 Tithe Map for the parish also shows us a large building on the site of the modern day chemical works; the Droitwich Workhouse (WSM10573). In 1836 an elected Board of Guardians formed the Droitwich Poor Union and created a working party whose ultimate goal was reached by the building of a new Workhouse on the road which became Union Lane. In was built by 1838 costing £4,000 and constructed to the design of the Workhouse architect Sampson Kempthorne. (Higginbotham, 2016)

Kempthorne’s “300 Pauper Model” which was simplified for rural areas. (Great Britain. Poor Law Commissioners, 1835)

Kempthorne’s “300 Pauper Model” which was simplified for rural areas. (Great Britain. Poor Law Commissioners, 1835)

The “200 Pauper Model” was a cut down version of Kempthorne’s large Square model used in urban areas with high numbers of poor, in rural Droitwich this consisted of a cruciform shape with the masters room and kitchens at it’s centre, flanked to the east and west by gender separated accommodation wings, a dining hall to the south wing and entrance block to the north with porters room and guardians board room. Work and utility blocks made up the sides of the square. An infirmary was added to the east, a vagrant’s ward positioned to the west at a later date, and a chapel was installed on the end of the south-east wing. (Higginbotham, 2016) (Droitwich DC, 1935-36).

Few photographs of the Droitwich Workhouse remain but Martley (above) was also built to the same 200 plan model and gives an idea of what it looked like. (Martley CC, Unknown Date).

Few photographs of the Droitwich Workhouse remain but Martley (above) was also built to the same 200 plan model and gives an idea of what it looked like. (Martley CC, Unknown Date).

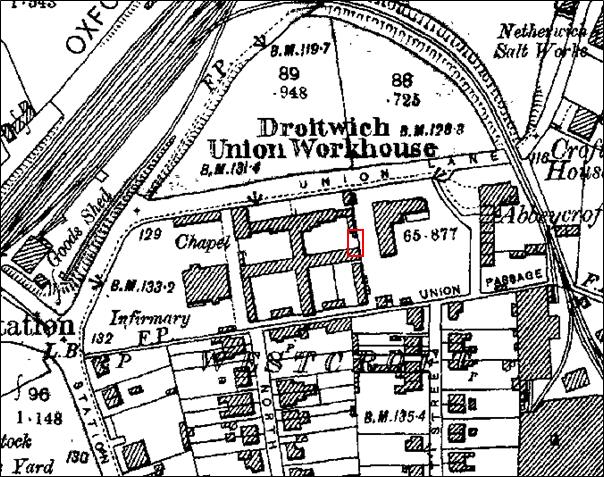

But did it have a basement? Unfortunately we do not have any detailed plan of the workhouse to tell us this. A plan accompanying sales documents from the 1930s available in the archives shows the extent of the building but provides no evidence for underground rooms (Droitwich DC, 1935-36). The 200 pauper model gives us a good idea about how the structure would have been built, but variations can be found throughout even the Workhouses built to the same plan in Worcestershire (Upton, Pershore, Martley). However, other plans produced by Kempthorne like the 300 pauper model are found to contain a basement store, usually below the Kitchen, suggesting such a room may have been built within the Droitwich workhouse. And when we overlay a map produced in the 1990s by Baxenden Chemicals on the supposed location of the buried room, onto the 2nd edition OS map dated to 1903, we can see that the buried room would have been located underneath the eastern buildings of the workhouse, just north of the chapel.

Approx site of buried room on 2nd Edition OS Map. Landmark digital mapping based on Ordnance Survey 2nd Edition, 1903 (Landmark reference number 39so8963. Original scale:25″ (1:2500)) © Crown copyright and database rights Ordnance Survey 100024230.

Approx site of buried room on 2nd Edition OS Map. Landmark digital mapping based on Ordnance Survey 2nd Edition, 1903 (Landmark reference number 39so8963. Original scale:25″ (1:2500)) © Crown copyright and database rights Ordnance Survey 100024230.

Could the secret room have been a basement in the Victorian workhouse or even a buried part of the chapel?

Would such a room in a workhouse have contained a mosaic floor?

By the 1860s geometric and patterned tile floors were becoming popular in public buildings and churches and by 1890 they were present in most terrace houses (Thompson, 2004). It is unlikely that the workhouse would have been built with tile flooring but as buildings like the chapel were added at later date a patterned tile floor may have been introduced and was certainly present in other workhouse buildings across the country. Further pursuance of the documentary evidence held within our original archive material may help to establish this fact, but this is probably the best evidence currently available for an actual structure on the site of the discovered buried room.

Overall, the evidence points strongly to the possibility that what was discovered on that momentous day was a well preserved basement belonging to the Workhouse with decorative tiled floor. But we cannot discount the Roman room theory, and if it is Roman that would be a fantastic discovery for Droitwich, the County and even the Country as intact tile mosaics from that period are rare. Of course, we may be discounting a whole host of other origins for the buried room and one way to discount the workhouse theory would be a full and proper investigation of the ledgers and minute books written by the Droitwich Board of Guardians during the time they caused the workhouse to be built. These documents are held by Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service and such an investigation may be the topic of a future blog post.

But the story might not end there. In 2013 Baxenden Chemicals announced the closure of its Union Lane plant and as of 2015 the whole site has been demolished down to slab level to prepare for future redevelopment.

Baxenden Chemical Works mid-demolition (Copyright Chris Whippet 2015)

Baxenden Chemical Works mid-demolition (Copyright Chris Whippet 2015)

Currently the secret room, as far as we are aware, continues to survive packed full of sand below the concrete cap placed to protect it by the workers at the alloy factory. If any future redevelopment poses a threat to this buried archaeology it will finally be brought into the light of day through excavation. But if it isn’t threatened it will go on keeping its secrets for future generations, the story of the secret buried villa fading with time to become a myth only whispered about in the back of The Old Cock Inn ….and personally I think that will be just as interesting.

By Andie Webley,

Historic Environment Record Assistant

Note: The WSM numbers contained within this blog refer to records within the Worcestershire Historic Environment Record, if you would like to know more about these or any of the records we hold you can visit us at The Hive or contact us.

Bibliography

- Droitwich Development Committee (1935-36) Correspondence relating to the purchase of property from Hesketh Estates Limited and the Droitwich Development Corporation; Union Buildings, Union Lane (with plan). (Worcestershire Archives Bulk Accession Number: 5987)

- Fox, D. (2011) The mosaics of bays meadow Roman Villa in Droitwich. Available at: https://researchworcestershire.wordpress.com/2011/01/23/the-mosaics-of-bays-meadow-roman-villa-in-droitwich/ (Accessed: 29 May 2016).

- Great Britain. Poor Law Commissioners (1835) Annual report, volume 1. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=inkXAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (Accessed: 29 May 2016).

- Greene, P.J. (1989) Norton Priory: The archaeology of a medieval religious house. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Higginbotham, P. (2012) The workhouse encyclopedia. United Kingdom: The History Press.

- Higginbotham, P. (2016) The Workhouse in Droitwich, Worcestershire. Available at: http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Droitwich/ (Accessed: 29 May 2016).

- Hurst, D. (ed.) (2006) Roman Droitwich: Dodderhill fort, bays meadow villa, and roadside settlement. United Kingdom: Council for British Archaeology.

- Martley CC (Unknown Date) Martley Workhouse Image, Martley Cricket Club. Available at: http://martley.play-cricket.com/website/web_pages/167741 (Accessed: 01/06/2016)

- Ruggeri, A. (2011) ‘Hidden beneath circus Maximus, an underground – and secret – Mithraic temple’,Archaeological sites, 21 February. Available at: http://www.revealedrome.com/2011/02/underground-circus-maximus-mithraic-cult-mithras-mithraeum-rome-subterranean.html (Accessed: 29 May 2016).

- Thompson, P. (2004) Victorian and Edwardian geometric and Encaustic tiled floors. Available at: http://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/tiles/tiles.htm (Accessed: 29 May 2016).

- Willis-Bund, J Page, W . (ed.) A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 2, ed. (London, 1906),

- Woodiwiss, S. (ed.) (1992) Iron age and Roman Salt production and the medieval town of Droitwich: Reports of excavations at the old Bowling Green and friar street. United Kingdom: Council for British Archaeology.

I worked for Baxenden Chemicals for over 20 years and the position of the mosaic was close to where my office was! To be clear, until 1993, this area of the site was occupied by Lloyds ladders, not Baxenden. I understand that Baxenden chemicals grew out of a former Victorian soap factory situated in building 65 -877 on your plan (next door to the work house). Later, a factory was built on the opposite side of Union Lane sometime in the 1960s. Lloyds vacated where the mosaic is around 1993, and we moved in soon after. There were rumours of the mosaic, but no one knew for certain where it was. Baxenden chemicals never made alloys and no manufacturing was ever done in the building where the mosaic was. It was purely a warehouse, so there was no need to excavate beneath the concrete (thankfully!). A former colleague of mine, Mike wall, researched the history of the factory I believe. I'd be very interested to hear of any further development and of course would be happy to provide any further background knowledge that I have.

Thank you for you comment, it is great to hear from someone who worked here. Thank you for pointing out that we missed the full name of W. A. Lloyds (Alloys) in the post – we have now corrected this. We will absolutely be updating this blog in the future with any further developments on the site and would welcome comments from yourself or any others that may have an interest in the area.