Back from conservation – Mytton Oak cremation urn

- 18th September 2017

Around 4000 years ago a 30-40 year old woman was cremated and her remains buried in an upturned pot, or burial urn. In 2015 we found this Bronze Age burial and carefully excavated the contents back in the office. Analysis of the urn and its contents has now been completed and the urn has recently come back from a conservation lab, where it has been stabilised. Now we want to share this regionally significant discovery with you.

Mytton Oak urn with flint knife (left) and fragment (right) found inside.

As some of you may remember, we excavated the predominately medieval site in Mytton Oak, Shrewsbury in 2015 – our environmental archaeologist Liz wrote a blog about the unusually large quantity of oats found there (you can read it here).

Along with medieval corn-drier and building were several Bronze Age features – a pair of parallel ditches, probably a trackway, a pit and the cremation burial. It may not sound like much, but the trackway tells us that there must have been areas of Bronze Age activity nearby that the route connected together. Cremation burials in this period tend to occur in cemeteries away from settlements, so it is possible that the excavation area was on the very edge of such a cemetery.

It was once we were back in the office that the story of this burial began to unravel. Richard and Jesse had carefully bandaged up the urn before lifting it from the ground, which kept it safe on the journey back to Worcester. Through a hole in the top (actually the pot’s base, as it was put in the ground upside down) Jesse carefully excavated the cremation deposit inside the urn, dividing the contents by the quadrant and spit (depth) it came from. You can see a timelapse of this micro-excavation below.

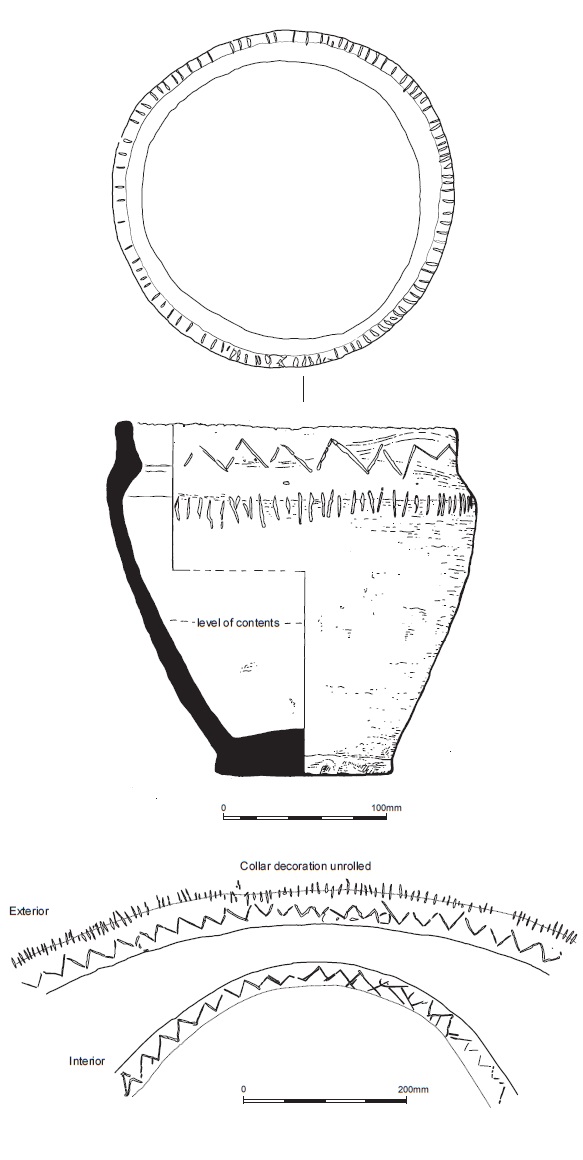

Now empty, the urn was studied by our finds specialist, Jane, and Neil Wilkin from the British Museum. They looked at the fabric of the pot (how it was made), the shape of it and decoration around the rim. It turns out that the urn is a bit of a puzzle, being the shape of a Food Vessel Urn but with decoration more typical of a Collared Urn. Both are types of Early Bronze Age funerary pots though, so we had a good idea of date. As is often the case with so called Food Vessel Urns, this pot has charred residues stuck to the inside, implying that it was used to hold food before being used as an urn. Laura, one of our illustrators, also produced a detailed drawing of the urn, creating a careful record of its exact shape and decoration.

Laura’s urn illustration

The cremated remains were sent off for analysis to Jacqueline McKinley, an osteoarchaeologist (human remains expert) who specialises in cremation burials. This work revealed that the Mytton Oak burial contains one of the greatest quantities of bone found in a single cremation burial from anywhere within Britain, of any date. Small fragments of cremated bone are often not collected up or missed, but great care was taken with this burial to collect as much as possible.

Staining on several fragments of bone suggests that copper alloy objects were also on the pyre – these may have been clothes fastening, personal adornments or small tools, such as a knife. A broken flint knife and another small piece of flint, also found in the urn, are heavily burnt and were presumably on the pyre as well. Everything collected up from the pyre seems to have been put into an organic bag, of textile or leather, before going into the urn for burial. This practice has been found in many other Bronze Age cremation burials and is identified by a tight cluster of bone within the urn, hence it’s important that the urn is carefully excavated in the first place!

Flint knife found inside urn

Less than a dozen Early Bronze Age cremation burials from the West Midlands had been scientifically dated at the last count in 2011. We have now added to this by radiocarbon dating a fragment of cremated bone and a sample of the burnt residue from inside the urn. Both samples came back with a similar date range of 1900-2000 BC, confirming that the urn and burial are as old as we thought. Another scientific technique, known as thin section petrographic analysis, identified exactly what the urn was made of. The clay and other natural resources used to make the pot can be found in the landscape near to Mytton Oak, although this in itself doesn’t prove that it was locally made.

So, now we know some facts, we are left to wonder at the human story of how and why this burial took place around 4000 years ago…

Illustration produced by Laura T

For every archaeological investigation we carry out, a technical report is produced that describes and discusses our findings. You can find the Mytton Oak report here.

Thank you for sharing this interesting excavation result.

We’re glad you enjoyed reading about it! Keep an eye out on here for future fieldwork news.

Now you can put it back where it belongs…

The land it was found on has now been developed, so it’s not possible to re-bury the cremation in the same location. What does happen, particularly to prehistoric human remains where their burial rites and wishes are not known, is a great ongoing ethical debate.