Harvests of the Past

- 3rd October 2017

Early autumn is a time when many take stock and give thanks for the year’s harvest. In the globalised world of today though, where supermarkets stock globally grown fresh produce all year round, harvest time has become less noticeable and, seemingly, less important to our availability of food. In a world before refrigerators, farm machinery and massive warehouses, what happened at the end of the harvest?

Over the past few decades, we have excavated many sites where people once processed and stored the cereal crops they had so laboriously harvested. As the evenings dim and weather cools, we thought that we’d share some of our most interesting sites with you.

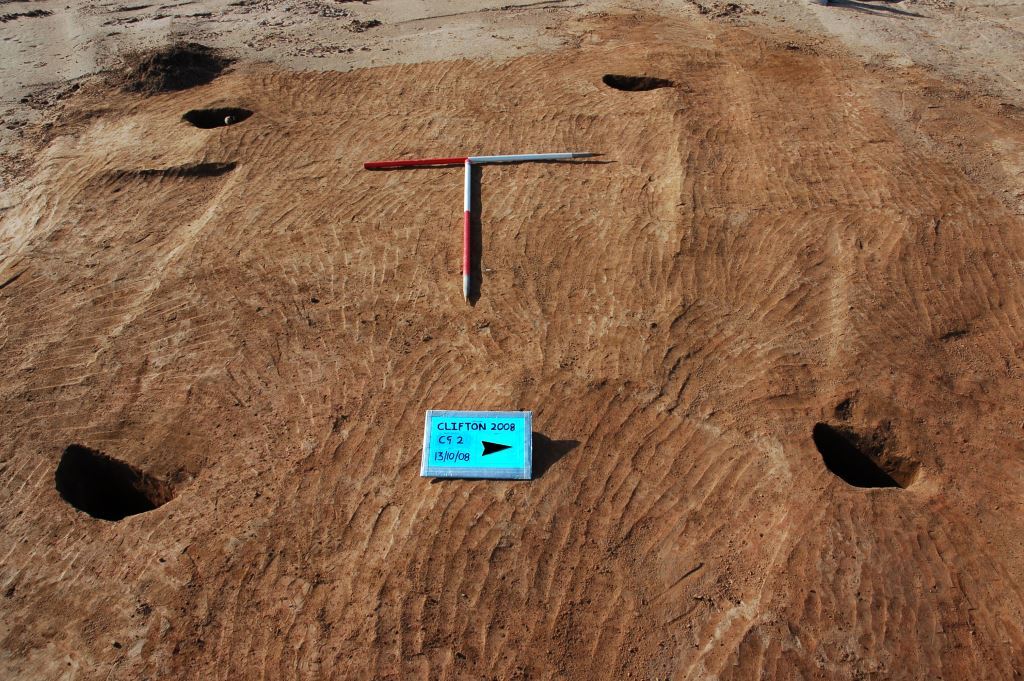

Turn back the clock to the 6th century BC and you will find Iron Age communities building and filling raised granary stores at what is now Clifton Quarry, Worcestershire. Between 600BC and 300BC, at least 89 of these so-called four-post structures were constructed. As the name implies, these smallish structures (generally 5 – 9m2) had a timber post at each corner and that’s about it. Or, at least, that pretty much all we see of them archaeologically. The lack of evidence for any walls or floor surfaces suggests that these buildings were on stilts. Occasionally, postholes of possible ladders are found too.

One of the excavated four-post structures at Clifton Quarry

What exactly these four-post structures looked like and were for has been much debated (six-poster do sometimes appear, but are comparatively rare). I would say that your guess is as good as mine, but we have one further piece of important evidence to help us understand what they are. Environmental samples taken from many of the postholes were rich in charred barley and spelt wheat, showing that both processed grain and unprocessed spikelets were stored there, away from rodents and the damp. Charred plant remains, as opposed to unburnt organic matter, are inedible to animals and micro-organisms, so can survive in the ground for millennia.

Our excavations at Clifton Quarry revealed a regionally unique Early to Middle Iron Age storage site, where harvested crops were stored in great quantities. One or two granary structures are commonly found in Late Bronze Age and Iron Age settlement, but the number of storage buildings seen at Clifton implies that a substantial community lived nearby.

Charred spelt and emmer wheat from Ryall

Fast forward several hundred years to the Late Iron Age in the region of what is now Ryall Quarry in Ripple, Worcestershire. Here we find people storing their harvested grain for the long winter in big pits rather than raised granaries, as the latter were probably more suited to short-term storage.

Liz, our environmental archaeologist, analysed samples taken by Cotswold Archaeology from six pits thought to have stored grain. A one litre soil sample containing 200 pieces of charred plant remains would be rich. Liz recorded 2000 to 11,854 fragments per litre from the Ryall pit samples, mostly of emmer wheat. Such a large quantity of charred cereal crop confirms that these pits were indeed grain storage pits. Similar deep circular storage pits have been found elsewhere in southern Britain on Iron Age sites, most famously at Danebury hillfort. Often lined and capped with clay, experimental archaeology has shown that fresh grain keeps well in storage pits over winter, as long as the seal remains intact.

Why did such a large amount of harvested crops burn? We’re not quite sure. Empty grain pits were often burnt before reuse to kill of mould and bugs, but there was no evidence of pests, such as grain weevils, and the pits seems to have been full when burnt. Whether intentional or not, a noticeable amount of the wheat harvest was lost. The grain stored at Ryall possibly weren’t from just one farm or one community though, as its location by the River Severn would have made it an ideal trading post.

Moving to our last site at Wellington Quarry, Herefordshire we find further evidence of farmer co-operating over their harvests. Corn driers have been used since Roman times to parch harvested grain before storage, and are still used today. At Wellington we found two medieval corn driers that were probably last used in the 13th or 14th century.

These large circular structures were 2m across with a sandstone floor, domed clay roof and a large stoke pit to feed them. Given the resources needed to build them, the corn driers were probably a community effort and filled with locally grown grain to dry. Whilst they’re typically found in farmyards, some were built in fields far from any settlement, as the Wellington corn driers seem to have been.

Medieval corndrier at Wellington Quarry

The nature of archaeology means that stored harvests are more visible to us than the act of harvesting, although sickles and other tools do appear in the archaeological record. The sites described here remind us though that whilst harvest time marks the end of the growing season, it also marks the start of storing food for winter.

If you would like to find out more about the sites discussed here, their publications are:

Full Ryall report available on the Cotswold Archaeology website

Jackson, R. & Mann, A. 2018 Clifton Quarry, Worcestershire: Pits, Posts and Cereals: Archaeological Investigations 2006-2009 Oxford, Oxbow Books

Jackson, R. & Miller, D. 2011 Wellington Quarry, Herefordshire (1986-96): Investigations of a landscape in the Lower Lugg Valley. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Dr Peter Reynolds, proved on our farm in the Vale of Evesham, that grains could be stored in pits, and then fed to animals. We supplied both the grains and animals in the late 60’s early 70’s for this to happen. He was proving Iron age structures, that had been found.