ArchI’ve Unearthed – Archaeological Archives

- 24th November 2017

We’re an unusual organisation: a joint archive and archaeology service. A marriage of muddy boots and spotless strongrooms. The word ‘archive’ has a different meaning for the archaeologists among us. An ‘archaeological archive’ includes the paper and digital records produced during an archaeological project.

Many archaeologists don’t dig: for those working on landscape surveys, recording historic buildings, or doing desk-based research, that paper and digital archive is the crucial primary record of their endeavours. But when we do dig, excavations are a destructive process: once a site is dug, you can’t go back and replicate the experiment. However, if records are meticulously created and preserved, you can reconstruct, re-examine, and revise your understanding of a site, long after it has disappeared beneath a housing estate or shopping centre.

When the spade goes into the ground, the archaeological archive also includes the artefacts discovered: traces of past lives such as fragments of pottery, building materials, animal bones, or stone tools. It also contains the evidence we gather to build our picture of landscapes and climate in the past: organic remains such as seeds, pollen samples, and residues from carefully sifted soil samples.

A pile of documents is not an archive until it is sorted, catalogued, stored, and made accessible by the efforts of archivists. Likewise, a boxful of broken pots is not in itself an archive. They need to be identified, recorded, labelled, and placed in the care of an institution that will make them accessible: to go on display, or into storage to answer the questions posed by future researchers. Ideally, archaeological archives will find their permanent home in the collections of a museum.

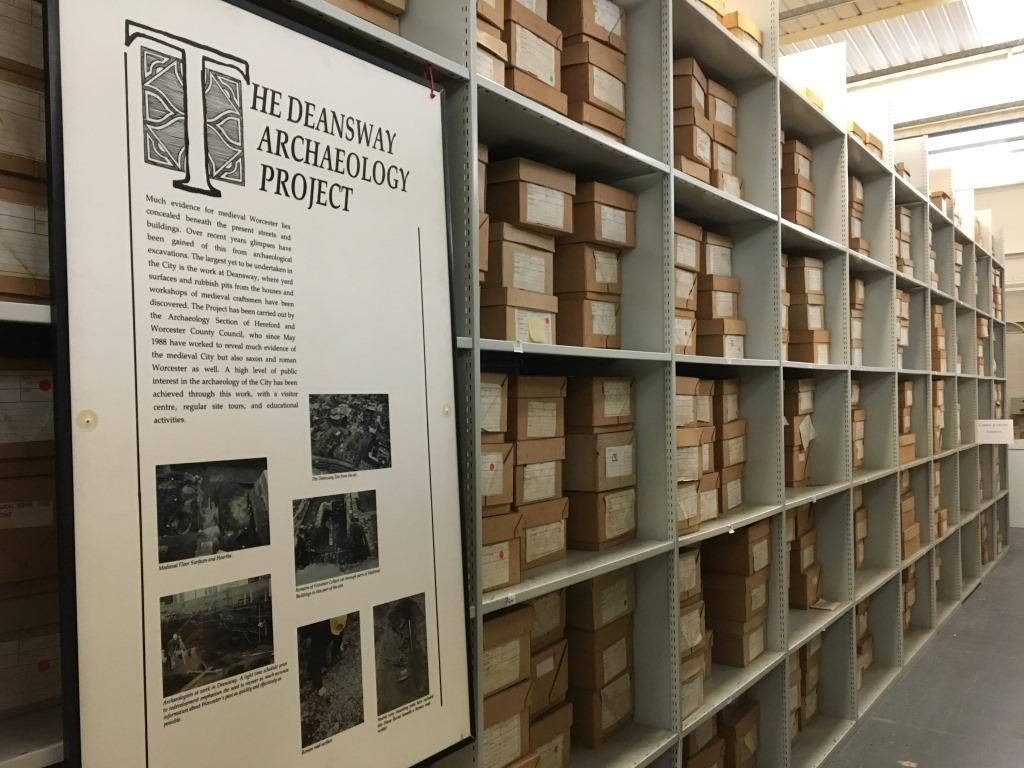

But museums in Britain are under pressure. Many have had to stop collecting archaeological archives. Of those who are still collecting, two-thirds expect to have to close their doors to new archives within the next five years. The volumes involved can be eye-watering. Perhaps the most famous archaeological site within Worcester was the 1988-9 ‘Deansway’ dig during the construction of the Crowngate Shopping Centre. It yielded 140,000 pieces of pottery and 115,000 fragments of animal bone. The animal bone alone fills 500 boxes.

500 boxes of animal bone from the 1988-9 Deansway excavations, Worcester

These archives take up a lot of space. Some require ongoing care and conservation, and even those which can sit unmonitored on a shelf cost money to store: warehouse space, lighting, heating, fire testing, purchasing shelves, arranging access… it all adds up. Charging for new deposits alleviates some of the pressure, but we’re still left with a legacy of old sites collected when budgets were less constrained. So, museums and archaeological organisations have been having difficult conversations about what sort of material we want to collect. Do we really need to keep it all?

In a word, no. In Worcestershire, we’re lucky to have a team of archaeologists and museum curators with a huge range of specialist knowledge. Even before a site is excavated, we now discuss what kind of archive may be produced, and which types of material are going to be a priority based on our existing knowledge. Roman Worcester was a centre for ironmaking; excavations here invariably produce tonnes of iron slag. We know a lot about it already, so only a small sample goes into the archive.

But what about existing collections? If we could get rid of some of those thousands of sherds of pottery, would it not free up some space? That’s the question WAAS archaeologists Derek Hurst and Rob Hedge, and Museums Worcestershire curator Deb Fox, have been grappling with this year. Historic England and the Society for Museum Archaeology commissioned research from museums across the country to look at the risks, costs, and practicalities of trimming down existing collections, a process known as ‘rationalisation’. Thanks to the herculean efforts of museum staff and volunteers we recorded 4768 boxes of finds from Worcester, from which we identified 3220 boxes that might be candidates for rationalisation according to the museum’s strict disposal criteria. The contents of those boxes were logged within 16,310 database entries, giving us a very detailed breakdown of the types of material that had been collected in the past.

Modern archaeologists frequently curse our antiquarian predecessors for keeping ‘star’ finds and discarding the everyday detritus which we prize and nurture. The big risk with rationalisation is the possibility that you’ll discard material that, with the arrival of a scientific breakthrough in ten or twenty years’ time, will prove to have been crucial in explaining the site. Recent advances in ancient DNA analysis, for example, mean that a wealth of new information can be extracted from old samples. Uninspiring lumps of charcoal in a small cardboard box from a 1957 dig on Iona have recently proved to be the key evidence vindicating the excavator’s theory that it was St Columba’s cell.

You can insure against the wrath of future archaeologists by ensuring that a sample is retained. If one pit contained 200 comprehensively recorded pieces of a common type of Roman pottery, you may be able to retain 10%. If a site has been published, it can be straightforward to identify material which may prove significant in the future. However, over a third of the museum’s collection is from unpublished sites. Even taking the time to delve into published sites can be expensive, so is a site-by-site audit a realistic solution? With a dwindling number of local authorities and museums having access to specialist archaeological knowledge, many museums won’t have anyone available who has the skills to carry out the task.

Our thoughts and findings, along with those of the other museums and archaeology services who took part in the project, will be published soon by the Society for Museum Archaeology. But along the way we’ve had the chance to peer into some fascinating stories. We’ll leave you with this one: in the mid-1980s, the Blackfriars dig (along the City Wall on the north side of Worcester’s Bus Station) encountered a large section of Roman Road; the upper layer was made from compacted iron slag. Proving impervious to picks and shovels, the resourceful archaeologists found a high-powered solution: a pneumatic drill. The fruits of their efforts were not in vain: a small and extremely heavy section of Roman road remains in the museum stores, and it’s not going anywhere!

Slag road and pneumatic drill excavation, Blackfriars, mid-1980s

I can well imagine the archive material which has built up since I was working on the pottery from the previous Deansway Excavation. I understand it must be a nightmare trying to store the huge amount of artifacts and the costs involved. Here in Crete where I worked at The Institute for Aegean Prehistory for East Crete, huge containers are either hired or bought to us for storage, with locks of course and kept outside. Just an idea you might like to think about. Best wishes. Rita

Hi Rita – yes, your Deansway material takes up a lot of space! And there’s been a lot more since, and it continues to come in. Some of the previous curators purchased some secure shipping containers. They work well for equipment storage or short-term transfer. Unfortunately, the weather in the English Midlands makes them less than ideal for long-term storage: once breached by rust damage, the contents got very damp. When we inspected them for this project, boxes had disintegrated and labels had become very hard to read!