A tale of two structures: ovens and wells in Medieval Evesham

- 5th March 2018

Stone structures are a tangible example of archaeology, often easy to see and appreciate. Being visible doesn’t make them any easier for the archaeologist to understand though.

A lot of the time, when people see archaeological sites it can be difficult to grasp what is going on. Archaeologists’ focus on what we call ‘features’, which can mean anything from pit to ditch, or wall to well. We set up string all over the place and dig odd seeming shapes out of the ground. There’s always method to this, as the relationships between features are often best seen in the side of the excavated slot created by our digging (‘section face’ in archaeological patter). Hence the string. Actual structures made of stone are much more tangible and usually offer a clearer picture to both the archaeologist and the casual observer. But sometimes they don’t. Back in the summer, we excavated a small site in the center of Evesham, where we discovered structures of both types – clear and unclear.

Medieval well excavated at Evesham, note the different coloured backfill deposits (1m scales)

The first structure was a lovely stone-built well. It is rare that we get to fully excavate a well to depth; they can go down beyond 8m, and to safely dig that deep one must step the ground – if you want to dig a metre down, you have to step a metre out. Very quickly you end up in a large crater. Also, most modern development won’t impact upon the lower levels of a well, so it can be preserved in situ. We managed to excavate to a depth of 2.2m by hand (and some judicious use of a mechanical excavator) and achieved an auger depth of a further 2.75m. Augers are narrow, hollow metal tubes you push into the ground to extract a sample of buried deposits. The well was probably built in the 13-14th century and fell out of use by the 17th century, after which it was backfilled with various soils and rubbish, including a lot of roof tiles and a leather shoe.

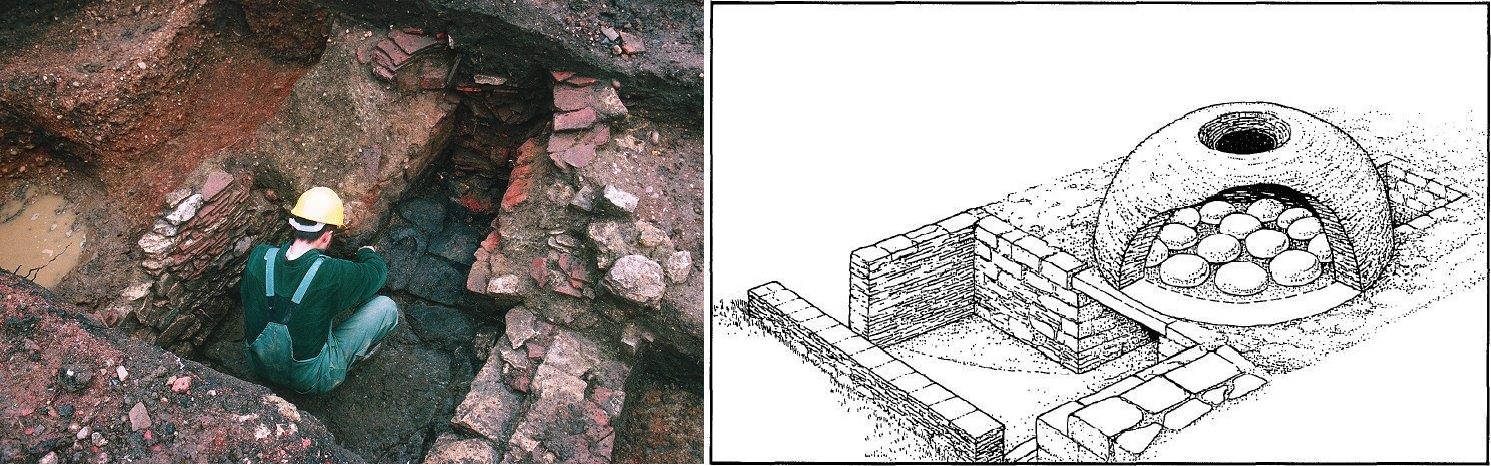

Medieval bread ovens – only the base remains (1m scales)

The other stone structure was a series of intercutting ovens, probably for baking bread on an industrial scale. These features are nowhere near as clear as the well, the survival of which has obviously benefited from being mainly underground. The ovens, by contrast, generally survived to just one course high. They were stone built, with the most complete oven featuring a straight flue leading into a circular fire pit. It can be very difficult to pick apart the sequence of these ovens when there are only bits of them remaining. Perhaps two or three separate structures are represented, or even four at a push. Secondly, it’s hard to develop a mental picture of what it looked like when complete. Fortunately, we dug a really good example of one in Pershore in 1994, and that enabled one of our illustrators to draw a recreation of it.

Pershore bread oven excavated by WAAS in 1994 & reconstruction illustration

So if it sometimes seems like archaeologists are making great leaps of faith in their interpretations of scrappy looking structures and random holes in the ground, remember that there’s method behind what we do.

Very interesting. Thank you!

Gosh, this stuff is so exciting. But, your description of the oven was so brief it left me clueless about where the fire was sited and whether there was a a firebox under it or the fire was lit inside the oven.

The Pershore oven had a fire underneath the floor that the food sat on, so that whatever was cooking didn’t come into contact with direct flames. In Evesham, the ovens weren’t as well preserved so it’s hard to be sure about their set up. It’s likely that they were similar to the Pershore oven though and had a floor suspended above the fire.