From Glass to Pixels

- 28th June 2018

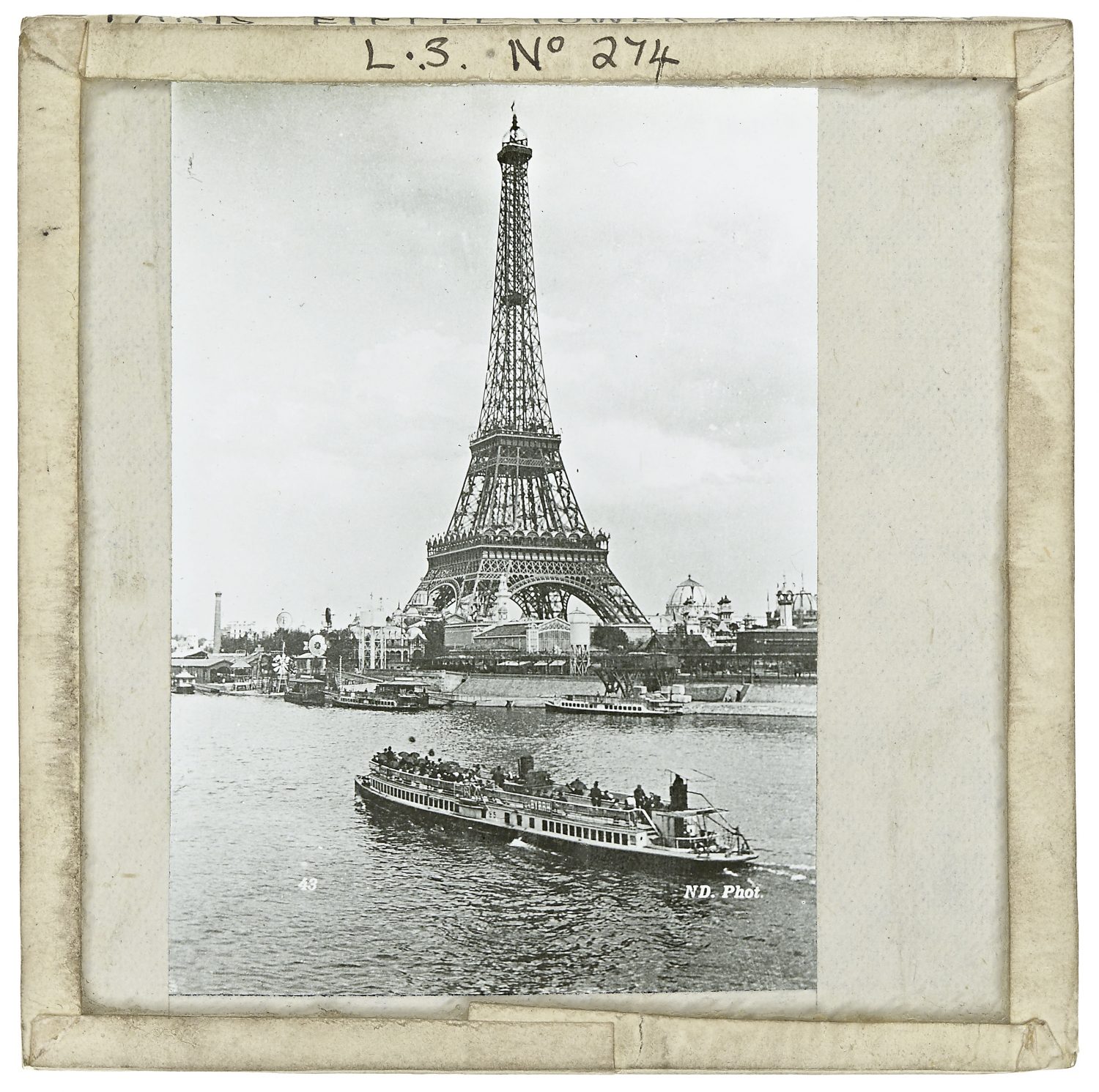

This may be difficult for some to believe but there was a time when it wasn’t possible to take a photograph with a telephone. In the pre-digital, pre-film age of photography there were no postcard-sized sleek and shiny smartphones to point-and-shoot, instantly producing an image of that perfect sunset with the ‘click’ of an artificial shutter release. No clever Apps to automatically enhance or restyle or artify the image or any social media to send it to. And, to get that all-important selfie of you and your cat at the top of the Eiffel Tower, you would first need to haul a camera the size of a bedside cabinet to your desired shooting position and hope that your back survived the trip. Worse still, the medium that the camera used to capture the image would have been a piece of glass.

Eiffel Tower, one of 2175 glass slides in the Whinfield Collection

Given the difficulties involved in using the first glass plate cameras and the obvious perils of having to use a material as fragile as glass on which to capture an image, its surprising how many plates survive today. That they do is partly because of the large numbers of plates produced by a growing number of early photographers attracted to a pastime, and profession, made more accessible by the technological advances of the period. During the mid-late 19th century, pioneers like like F. Scott Archer and RL Maddox, developed methods of hand-coating glass with light-sensitive chemicals to capture an image. This process, seen as an improvement on earlier methods like the daguerreotype, helped to attract more practitioners and the popularity of photography was given a further boost when less expensive, machine-coated plates began to be mass produced in the 1870s and cameras became smaller and little bit more portable – more the size of a tea caddy than a bedside cabinet.

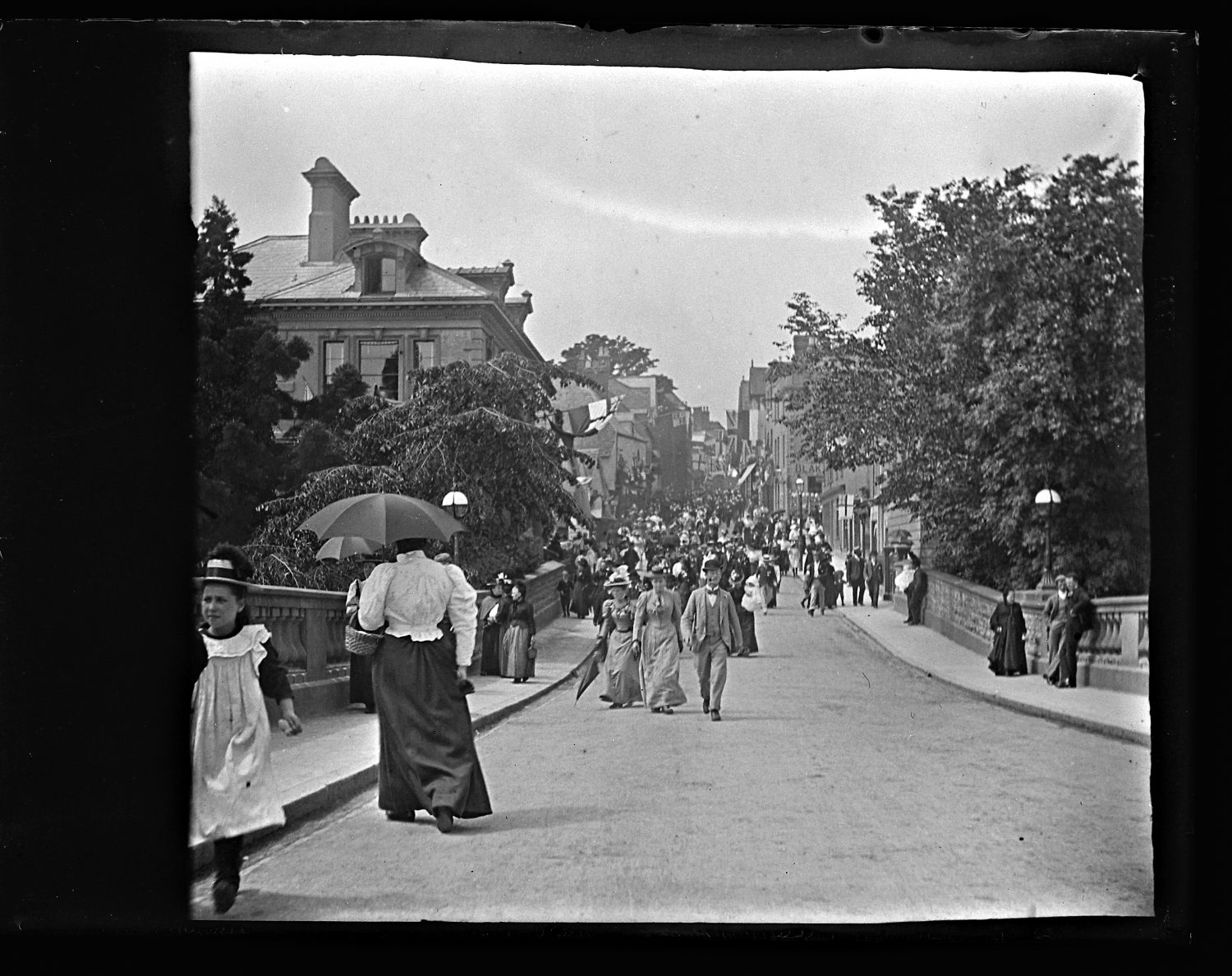

Evesham, one of a large number of glass slides held in the archives here

Here at the Hive, WAAS Digital, the archival photography arm of the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service, has recently been involved in digitising some of the thousands of plates we have safely stored in our archives including the Whinfield collection of glass magic lantern slides. Unlike some commercial digitisation bureaux we don’t mass scan glass-plates or any of the other materials or transparencies we work with like strip film and 35mm slides. Instead, each plate is individually assessed, cleaned and then photographed using a medium format camera fitted with a high-resolution digital capture sensor and the resulting image processed in specialist image capture and processing software.

By this route, and in the time it would take the chemicals on a newly coated glass-plate to dry, we are able to create, enhance, save, and make available on-line, a perfect digital copy of each glass plate. Doing so allows us to both preserve the delicate glass-plate originals by creating high-quality digital surrogates and, as in the examples shown here, open up world-wide access to some of the work of these early photographers who didn’t have telephones that can create pictures but who were adept at using the embryonic photographic technologies of their time to capture images of the different worlds around them. In a similar way, we are using our 21st century photographic technology and techniques to convert their images-on-glass into pixels to further preserve those captured moments for future generations – although we probably have it a little bit easier.

If you have glass slides and need someone to print or digitise them please get in touch using our online enquiry form.

A group of runners on Worcester High Street. One of many glass slides from over 100 years ago held here in the archives.

Yes ! but don’t you think those black and white photo’s were much clearer and sharper, much like the old black and white movies.

Yes, some of the early glass plates photos are incredibly sharp, and with some it is so hard to believe that they are 100+ years old as they look so fresh. It’s one of the reasons we like them so much.

The Evening News & Times in Worcester still used a few glass negatives in the early 1960’s. Presumably it was cheaper than using only a couple of negatives from a film.