The Charles Archive: The Plough Inn – The one that got away

- 9th July 2018

This is the sixth in a series of blog posts celebrating the life and work of timber-frame building specialists FWB ‘Freddie’ and Mary Charles. Funded by Historic England, the ‘Charles Archive’ project aims to digitise and make more accessible the Charles Archive collection.

In this piece we will be looking at a building that no longer survives – a building that fell victim to the redevelopment of the east side of Worcester City Centre in the early 1970s, making way for City Walls Road.

One might be forgiven for believing that the Plough Inn in Silver Street was rather unimportant – ‘a wholly unprepossessing Victorian travesty’ as Freddie himself puts it in his rather dramatic way. The building had clearly been heavily altered over the years and what was left at the time of demolition in 1972 was a rather tired-looking, back street boozer, clad in early 20th-century mock Tudor framing.

View along Silver Street (from the north) before demolition. The mock-Tudor framing of The Plough can be seen at the end of the street. (The Worcester City Historic Environment Record Conservation Photograph Collection).

The Plough in 1951. (The Worcester City Historic Environment Record Conservation Photograph Collection).

Noake believed that the Plough, once known as the Archangel or Angel, dated to around 1715, however, what remained of the building appears to have predated this by at least a century.

The Plough Inn, Silver Street, partially demolished (with thanks to the Changing Face of Worcester)

The file in the Charles collection relating to the Plough Inn is not at all substantial, but is rather revealing in its content nonetheless. It emerges that Freddie arrived on the scene of this building’s impending doom when already partly demolished. He was able to rapidly assess what remained of the structure and from there produced an idea of how the original structure may have looked, drawing on his experience of timber-framed buildings from across the city, including Warndon Court Farmhouse and Nash House in New Street, where he had an office for some years. He notes:

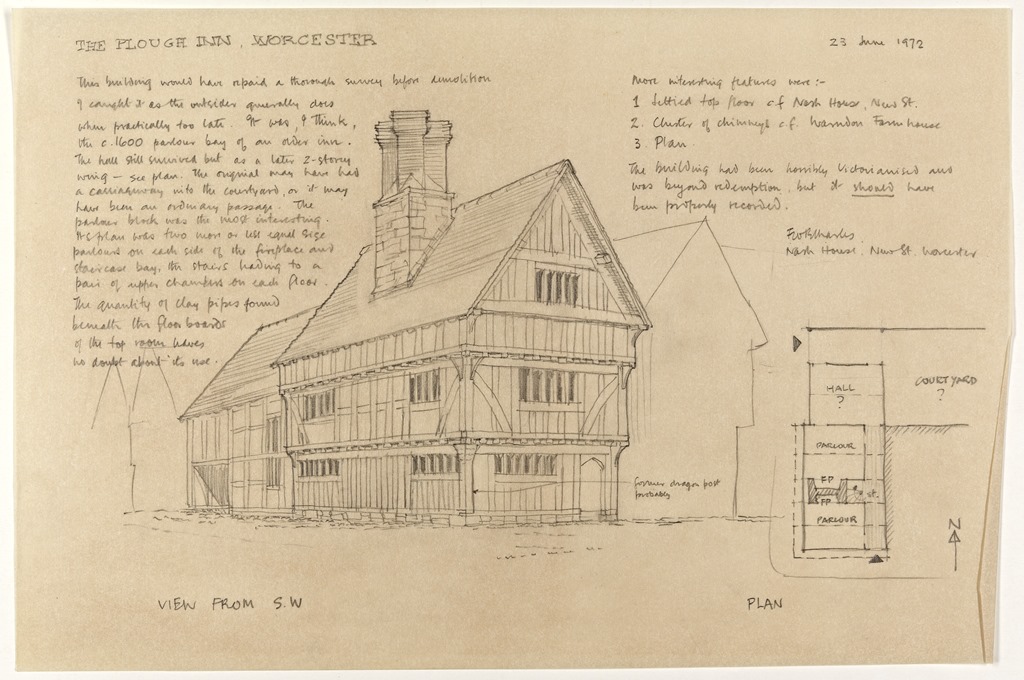

“This building would have repaid a thorough survey before demolition. I caught it as the outsider generally does when practically too late. It was, I think, the c1600 parlour bay of an older inn. The hall still survived but as a later 2-storey wing – see plan. The original may have had a carriageway into the courtyard or it may have been an ordinary passage. The parlour block was the most interesting. Its plan was two more or less equal size parlours on each side of the fireplace and staircase bay, the stairs leading to a pair of upper chambers on each floor. The quantity of clay pipes found beneath the floor boards of the top room leaves no doubt about its use.”

Reconstruction drawing and notes on The Plough Inn, Worcester by FWB Charles © Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service Charles Archive Collection.

In many ways what is even more interesting is Mr Charles’ views that come through in the dissemination of this survey. He signs off the sketch survey drawing with his opinion of what transpired here:

“The building had been horribly Victorianised and was beyond redemption but it should have been properly recorded.”

The fervency of his view seems to be emphasised by the underlining of the word ‘should’, but was further emphasised by a handful of copy letters that he had sent to various people. He writes with passion to both the Ancient Monuments Records Section in London and Mr McKee at the Corporation of Worcester, stating variously that “the Local Authority takes absolutely no notice of anything unlisted” and expressing his concern (or more likely outrage) that “the building had disappeared without any official record. This shows the fallacy of listing buildings as has been shown a thousand times before”. He rather downplays the value of his work through these communications however, referring to his “rather inadequate sketch” which the reader might like as “a momento rather than a record”.

Whether inadequate or not, his work remains perhaps the only record we have of a building whose survival beyond the Civil War was somewhat miraculous. Archaeological evidence from recent excavations at the St Martins Quarter precinct suggests that the Plough Inn seems to have survived the destruction of the Civil War, when all around was levelled to deny besiegers hiding places near the city walls. This was surely the result of its location within a bastion rampart, part of the Civil War defences just outside St Martins Gate. Most likely it was partly buried by the soil dug from the bastion ditch (which was re-excavated by archaeologists in 2010) and used as accommodation by the forward gunners during the defence of the city. A cannonball found during the excavation may have come from one of the Parliamentary guns stationed on Shrub Hill during the 1646 siege of Worcester. As Mr Charles emphasised, this building really should have been properly recorded!

This is a guest blog by Sheena Payne-Lunn, Historic Environment Record Officer for Worcester City Council, who has been working with us on the project.

![]()

I love these timber framed buildings so much so that we purchased a timber framed cottage some years ago. It was situated near Leintwardine and Hopton Heath. but I can’t remember if it came under Worcestershire or Shropshire.