Discovering Lost Landscapes – The William Smith Geology Map

- 7th August 2018

Emma Hancox, Sam Wilson and John France

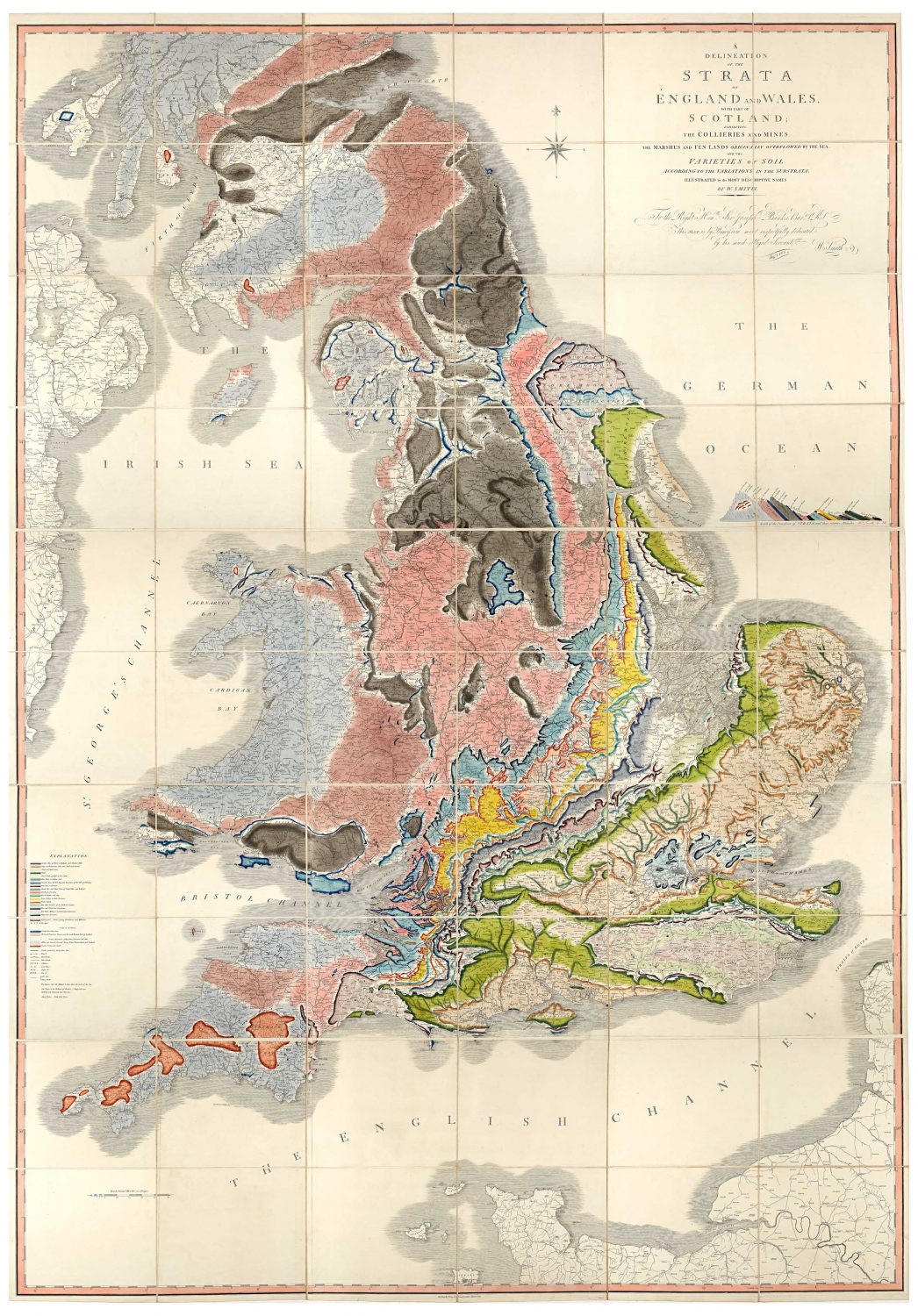

This summer, as part of the Lost Landscapes project, we are exhibiting a copy of the first geology map of Great Britain, produced in 1815 by William Smith. A private donor is kindly lending us his copy of this rare map for the Ice Age exhibition in the Art Gallery and Museum. We also have a giant print of the map in The Hive as part of the Origins of Us exhibition.

Known as “the map that changed the world”, the giant print forms the centre-piece of Origins of Us. This exhibition explores how we came to understand our human story. Set against the back drop of Darwin’s Origin of Species and the emergence of our understanding of the antiquity of the earth, the story of how 19th century scholars and collectors came to revelations about the age of the rocks, fossils and human-made artefacts around us, which spoke of distant aeons, is the story of how we understand what it means to be human.

William Smith (1769 – 1839) was a mineral surveyor and geologist. His life story is well-referenced as a bittersweet tale of persistence against academic adversity whose significance was only truly recognised after decades of hardship. During the course of his early work in Somerset coal mines he noticed that rock layers were always laid down in a predictable pattern, and that these layers could be found in the same pattern across great distances. He also noticed that the same fossils occurred in particular layers, and this helped to formulate his understanding of geology.

His geological map was the result of these years of work as a mineral surveyor. Though William Maclure had produced a geological map of the (then much smaller) USA six years previously, one only has to glimpse both maps to see the increased level of detail of Smith’s over such a large area. The map presented both the results of his widespread surveying and also his theory on stratigraphy that non-contiguous regions of Britain could have their strata matched through identification of similar fossil assemblages embedded in the rock. These convincingly suggest that he deserves the title of ‘The Father of English Geology’.

One of the most impressive aspects of Smith’s maps is the collation of methodologies (his map’s ‘canvas’ was based on an existing John Cary map of the British Isles) and observations derived from his own surveying in order to represent a complex and extensive set of data visually. Additional to their pleasing aesthetics, they would have served as a decent point of reference for anyone undertaking novel geological research and, considering aspects of his original map (such as a three-dimensional depiction of strata and landscape as a legend of its own) are common components of geographical practise today, undoubtedly contributed to subsequent geological discoveries since.

We created a digital version of this copy of the map as part of the Lost Landscapes project to allow it to be more widely accessible and preserve the beauty of the fragile original. About 400 copies were made originally but only a quarter of those survive and many are now damaged or incomplete. Other copies of this map have been photographed before, but this copy is particularly well preserved, and each copy is unique because every copy was hand drawn and dated by William Smith. Amendments or changes were often made on subsequent copies as knowledge increased; taken together, the maps show the evolution of knowledge at that time.

This map was borrowed for the photography in December 2017 from its permanent home at Dudley Museum at The Archives. Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service has a digitisation team in The Hive. Using state-of-the-art photographic equipment, the team produces high-quality digital copies of traditional materials including books, maps and photographic prints.

One of our digitisation team in action

The main challenge when digitally photographing any large map is how to ensure legibility and clarity of the smaller details while at the same time managing to produce an image of the whole document. In this case, the map in its original physical form is divided into three separate foldable sections which made the task of manipulating it a little easier and allowed smaller areas of each section to be photographed at a closer camera range to capture the detail.

Using a tethered digital camera, the top, middle, and bottom sections of the map were each photographed in smaller pieces producing a total of fifteen separate high-resolution images. The smaller pieces of each section were digitally stitched together to produce a full image of that section and the three completed top, middle and bottom sections were then finally stitched together to create an image of the full map. It would be possible to manipulate the digital image to hide the individual map panes and produce a seamless map, but this would not be a true representation of the original map.

You can find out more about the map in a special event on Thursday 23 August. Dr Jonathan Larwood will be delivering a talk on the origins of this groundbreaking map here in The Hive. It is free to attend, but booking required here.

The Worcestershire section of the map

Post a Comment