The Charles Archive: 43-49 St John’s – The one that almost got away

- 30th August 2018

This is the tenth in a series of blog posts celebrating the life and work of timber-frame building specialists FWB ‘Freddie’ and Mary Charles. Funded by Historic England, the ‘Charles Archive’ project aims to digitise and make more accessible the Charles collection.

In some of our previous posts we have explored buildings where Freddie was involved in recording works but where ultimately the building was demolished. Here we look at a building where he provided critical support to a local campaign to save an important historic building in the heart of St John’s, Worcester.

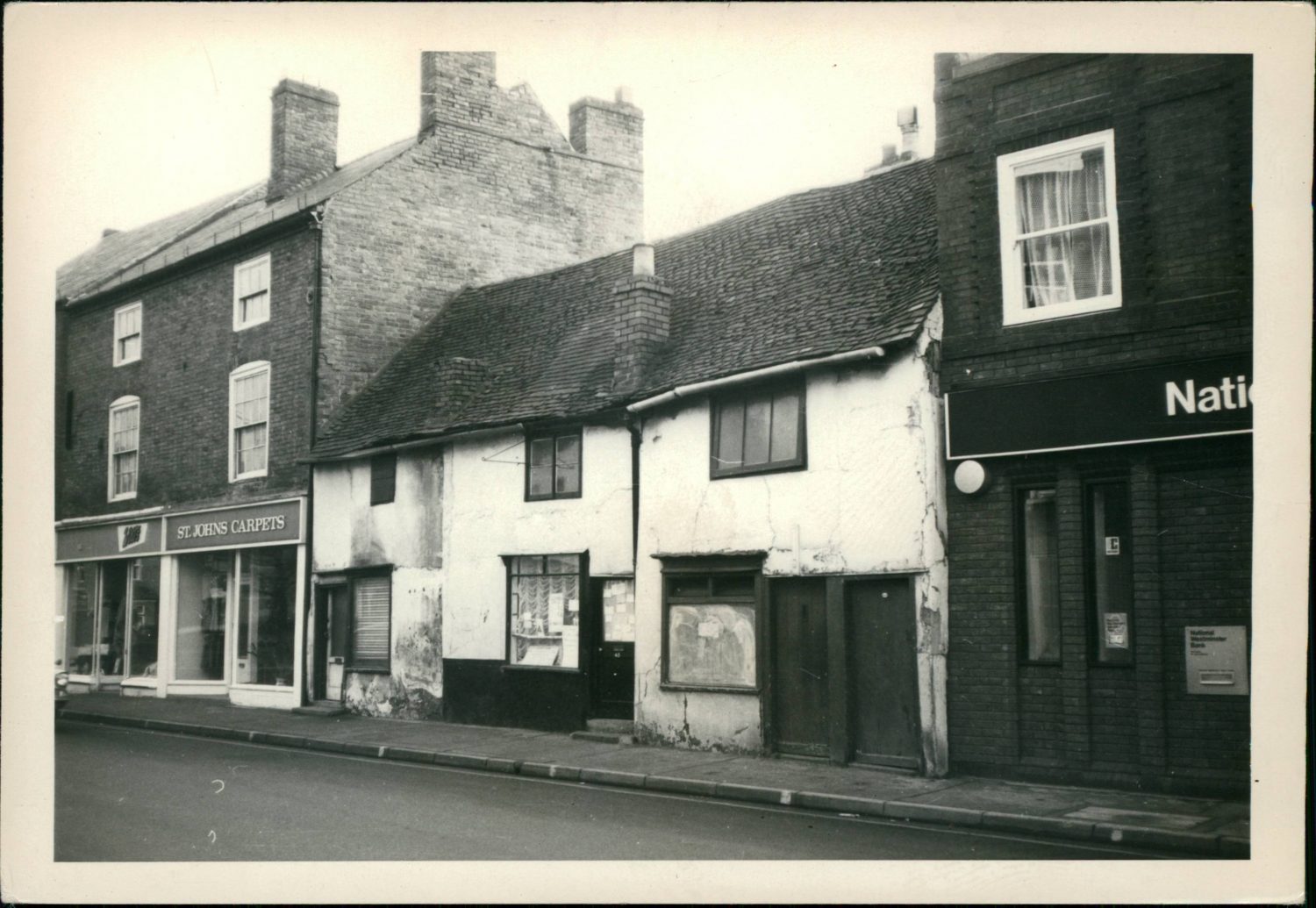

In 1973, a small, neglected row of properties on the main street through St John’s was proposed by its owners Giffard Mercia Ltd, for demolition. The land agents managing the site submitted an outline application shortly followed by a Listed Building consent application for demolition with a covering letter stating that ‘the present buildings have reached the end of their useful life and have no particular architectural merit’. The buildings had been listed in 1971 as ‘probably 17th-century with alterations’.

43-49 St John’s in 1973 (Worcester City Conservation Photograph Collection)

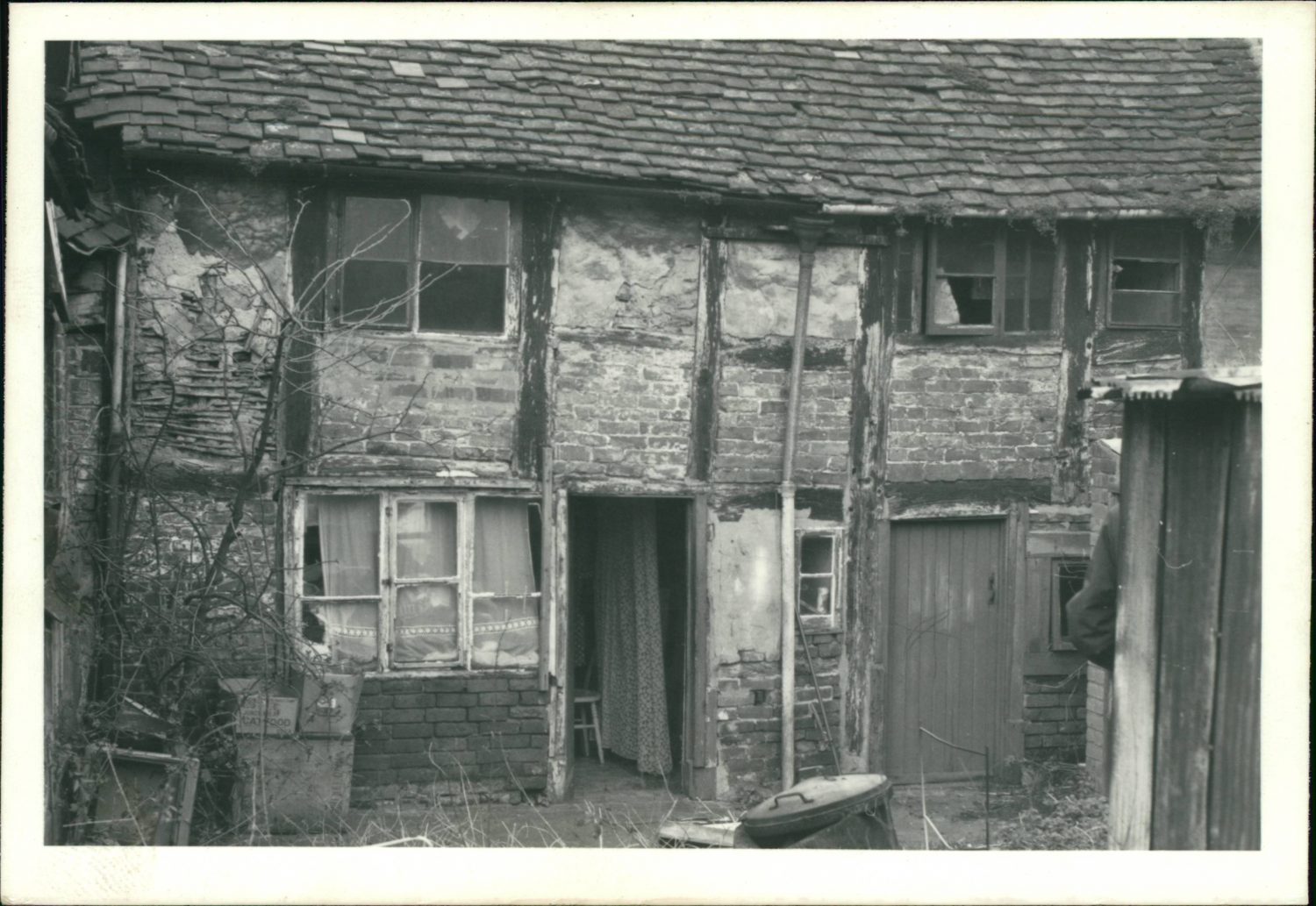

The rear of the property in 1973 (Worcester City Conservation Photograph Collection)

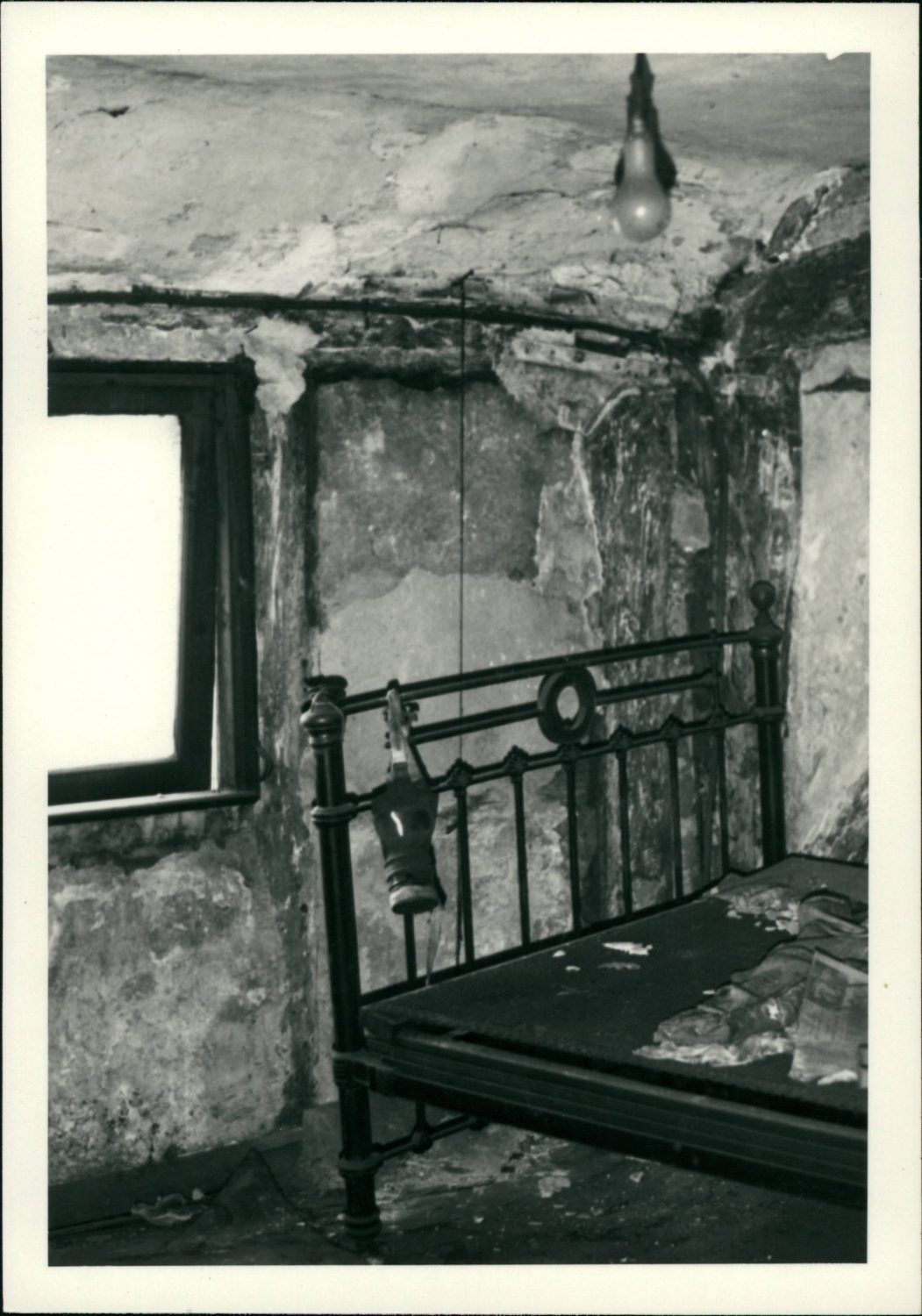

Various options for the building were considered by the City Council in reaching a conclusion over its proposed demolition, including the availability of grants for restoration. It was considered however, that under the provision of Section 10 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1972 which established the possibility of obtaining a grant from the Department for the Environment, that the building would not be eligible since the city council ‘were not aware that 43-49 St John’s was considered to be of outstanding importance’. This opinion can be found in a number of places within the planning documentation and is an interesting insight into the attitudes at that time towards those buildings listed at Grade II, that they were not considered to be of high importance. The estimated cost of restoration was considered to be too high to be economically viable and they were even advised that in view of the buildings structural condition it might not even stand up to the rigour of restoration. Further, the Environmental Health Officer advised that in order to satisfy the conditions of the Housing Act 1957 with regard to making properties fit for human habitation, it would be necessary to completely demolish and rebuild the properties.

“Unfit for human habitation” (Worcester City Conservation Photograph Collection)

The application for listed building consent was considered by the Development Committee on 18th October 1974 and resolved to grant consent on the provision that “Demolition of the said properties shall not take place until details of the proposed development have been approved by the Council”.

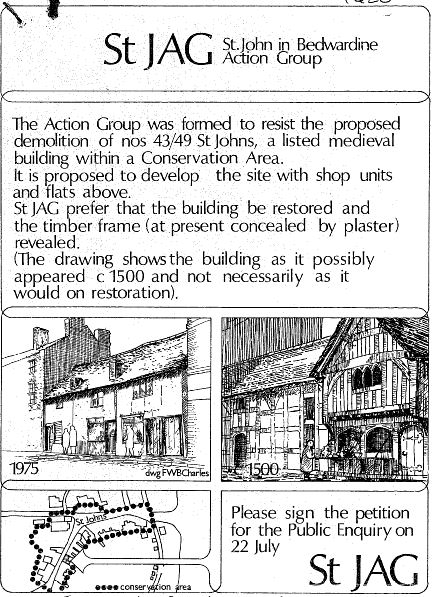

St JAG Campaign leaflet making use of reconstruction drawing by FWB Charles (from planning file 73-1420)

Following this decision and its advertisement in the Evening News, a number of objections were made and a concerted campaign began to gather momentum. Shortly after the consent was announced, St JAG – the St John’s Amenity Group was formed to fight for the survival of 43-49 St John’s. The application was called in by the Secretary of State and a Public Inquiry announced for the following year.

The first involvement that Freddie and Mary Charles appear to have had with this case was in November 1973 when Freddie wrote formally to the City Council: “We wish to object to the demolition of these three bays of interesting sixteenth century buildings. The framing except for part of the street front and one end wall is virtually complete, much of it in good order and the whole capable and worthy of restoration”. It is not clear at what point Mr Charles gained access to the buildings, but as a result of his visit he was able to reprise their understanding from a row of fairly ordinary 17th-century cottages to an important medieval hall. A detailed survey and reconstruction drawings were produced and strong proof of evidence was presented on behalf of the St John’s Action Group to the Inspector in attendance at the Public Inquiry.

In his report, Charles stated:

“I am opposed to demolition of this group of buildings on grounds that it is historically and architecturally worthy of preservation in its own right and that it is capable of repair and being brought up-to-date for modern use without loss of its true identity”.

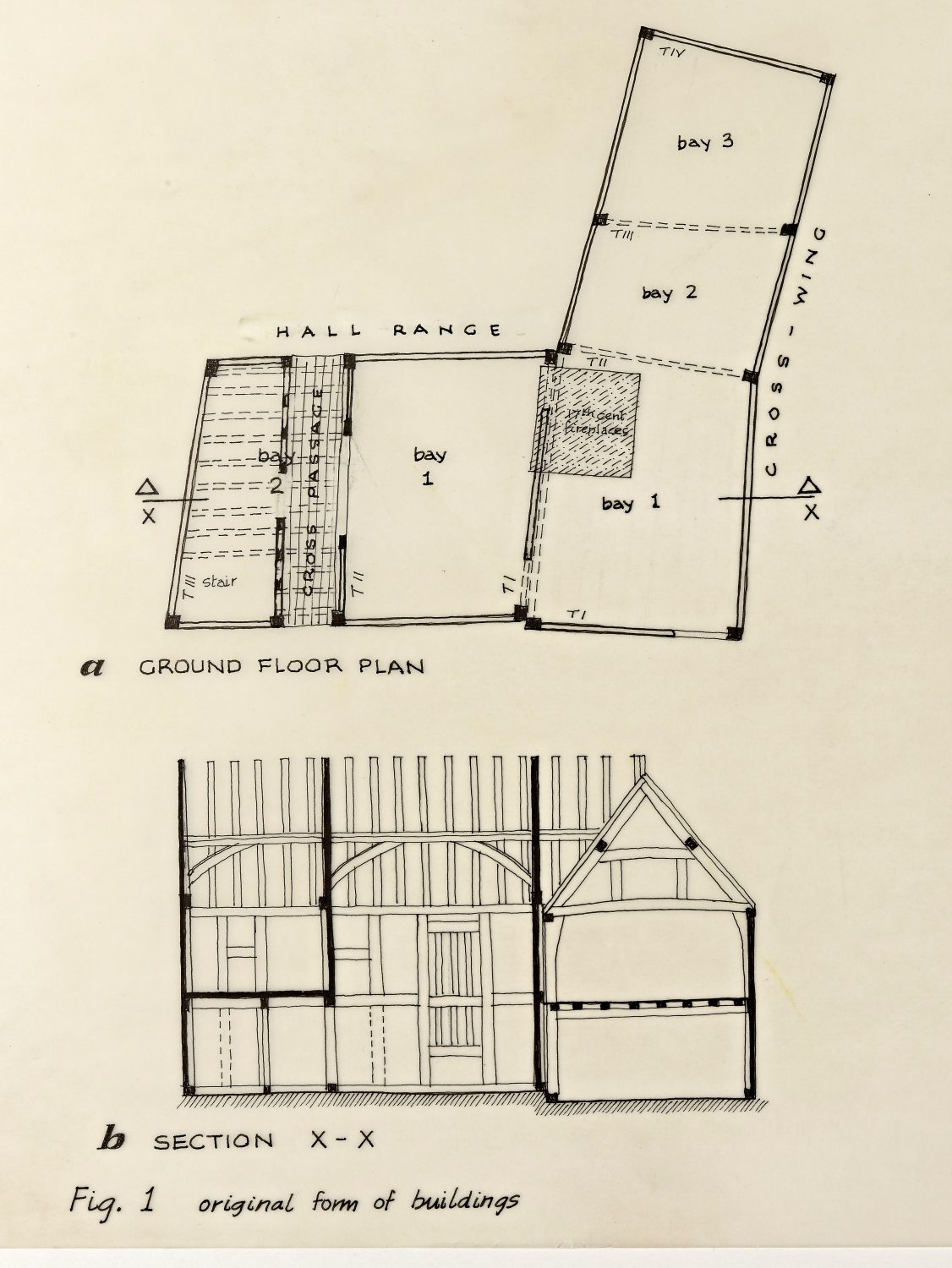

Drawings were produced in plan and section showing the form of the hall-range and cross-wing in c1500, their most likely date of construction. This was clearly evidenced and the report made reference to bay 1 being originally open from ground floor to roof, that bay 2 contained vestiges of a cross passage and that the roof structure was typical of late medieval domestic design in the region.

Original reconstruction drawing by FWB Charles (BA13218-1-15)

Building plan and section by FWB Charles (BA13218-1-15)

Freddie concludes his report setting out the case for restoration. He sets out the need to record every detail of the original construction, after which “it is a simple matter to repair and replace the defective and missing members”. He draws on his extensive experience of the value of restoration stating that “invariably the restored building in an old street becomes the main attraction in the locality, giving a lead for conservation in an area far wider than one would expect its influence to extend”. He also emphasises his philosophy that restoration produces buildings with “better commercial prospects than can generally be provided by demolition and building new. And they have the added advantage for the developer that he earns public appreciation instead of reproach and execration”!

The weight of opposition in light of Freddie’s report began to stack up, with Worcester Civic Society reversing their original support for the demolition scheme, and in an unusual twist, even the County Planning Department standing in opposition. While the Environmental Health Officer gave evidence stating that “the structure and fabric of these properties are in an advanced state of decay and are unfit for human habitation” he also noted that the buildings were included on the list of slum clearance properties approved by the ministry in 1954.

The Inspector weighed up the evidence and considered that “insufficient consideration has been given to the building being put to some public use” and that in his opinion “the demolition of the whole building is unjustified”.

He recommended that listed building consent to the demolition of 43, 45, 47 and 49 St John’s, Worcester be refused. The building lived to see not only another day, but its rescue from further decay by one Mr Alfred Taylor, a local man, who’s legacy was to be the complete restoration of this important medieval building.

This is a guest blog by Sheena Payne-Lunn, Historic Environment Record Officer for Worcester City Council, who has been working with us on the project.

![]()

Oh !! I was so pleased these lovely buildings were restored. They have such character unlike modern buildings of today.

Thank goodness for Freddie and Mary Charles & Historic England! It’s a beautiful building! Great to learn about its history.