The Charles Archive: A Pioneering Approach to Understanding Timber Buildings

- 7th September 2018

This is the eleventh in a series of blog posts celebrating the life and work of timber frame building specialists FWB ‘Freddie’ and Mary Charles. Funded by Historic England, the ‘Charles Archive’ project aims to digitise and make more accessible the Charles Archive collection.

The work and ideas of Freddie Charles can go a long way to illustrate the development of timber structures and their regional variation. In particular Charles was of the school that many of the timber techniques used within our region are variations based originally on cruck framed structures as outlined in Medieval Cruck Building and its Derivatives (Charles 1967) and Conservation of Timber Buildings (Charles and Charles 1984). Whilst some of these ideas now seem out dated, many still hold weight with modern researchers (Alcock and Miles 2013).

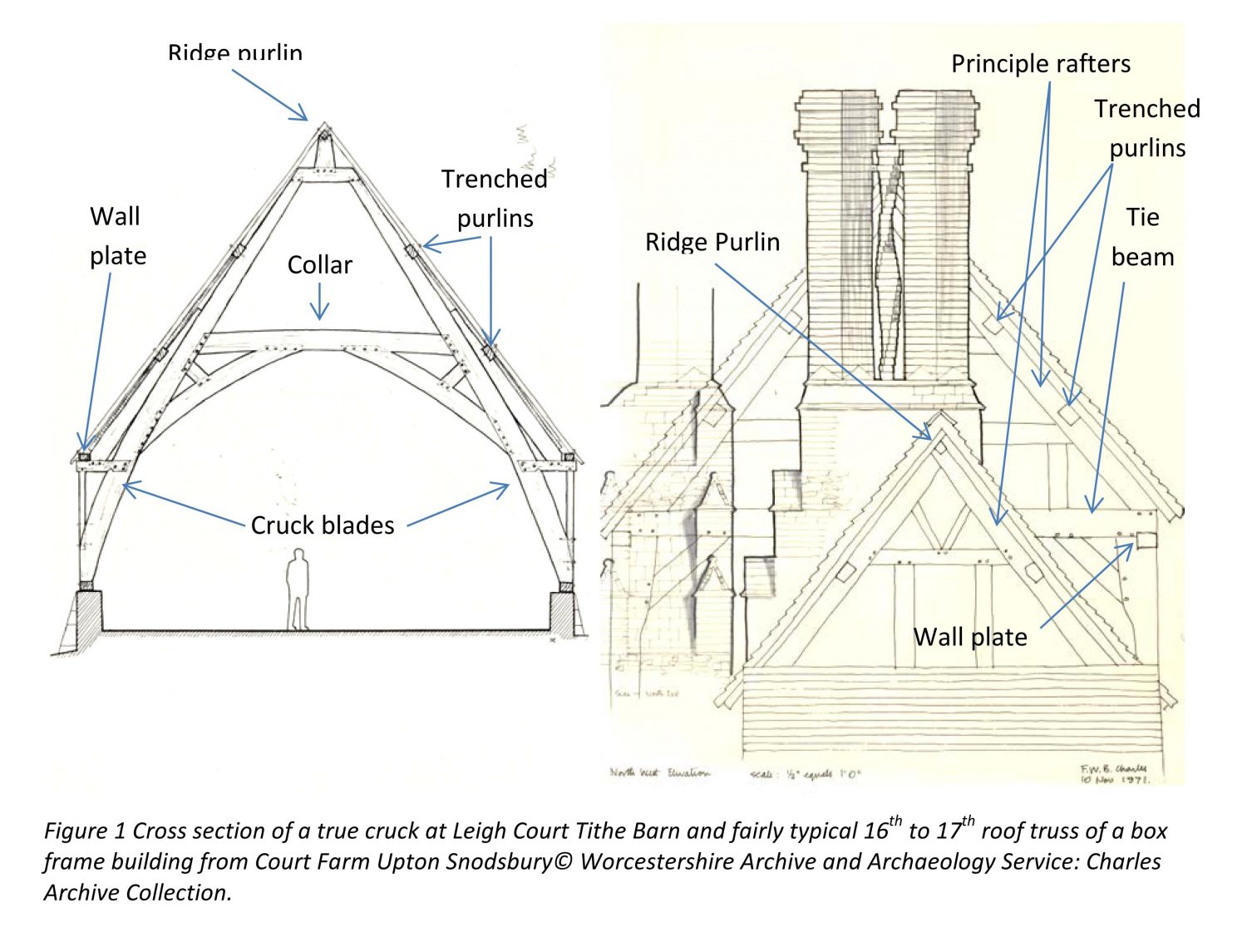

Charles regarded the “true cruck” structure, as in the example from Leigh Court Tithe Barn on Figure 1, as likely to have been archaic (a “true cruck” being a cross frame truss with a single timber on each side running from the floor or a low cill wall and supporting the apex of the roof). In most basic form it could have been poles placed on or dug into the ground and lent together to create the roof truss. He cited documentary evidence for the type from 8th century Ireland as well as corbel built stone structures, also from Ireland, which create the same profile. No conclusive direct evidence for such timber structures exists in the below ground archaeological record. The earliest known true cruck dates to 1262 from Cottingham, in Northamptonshire (Hill 2005), with the later end of the tradition around 1550 in Shropshire (Moran 2003) as is broadly similar in Worcestershire. These buildings remain present across much of Britain, with the notable exception of the south-east of England.

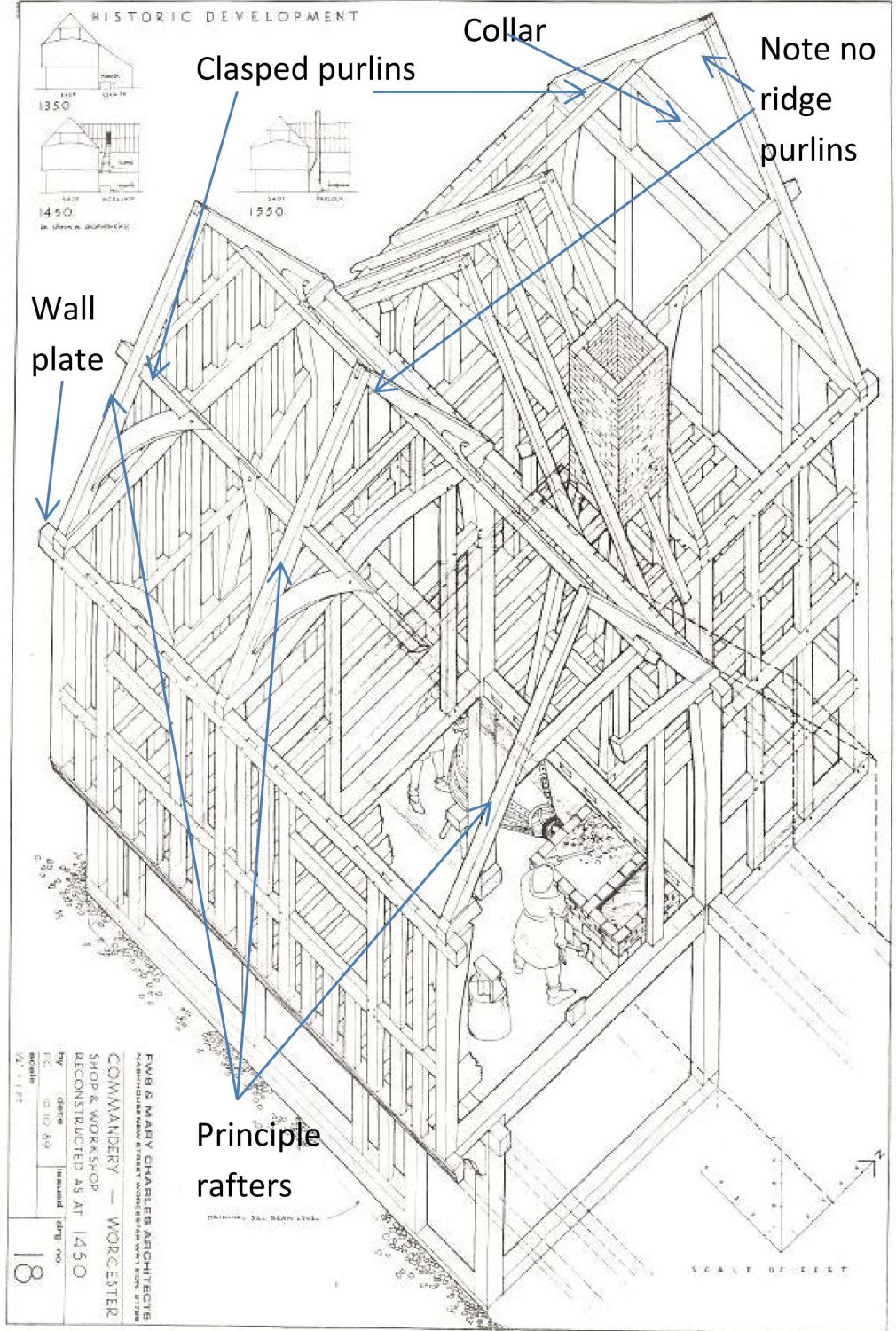

It is almost ubiquitous within our region that purlins are cut into or “trenched” into the upper side of principle rafters on box framed buildings, as is shown on the roof drawings from Court Farm Upton Snodsbury on Figure 1 above. Within the south-east of England where true crucks are not present, the “clasped” purlin continued in use even into the 19th century. Within this method of construction, the purlin was clasped between the underside of the principle rafter and the upper side of the collar. This method is certainly not unknown in Worcestershire in the later medieval period, as shown at the Commandery in Worcester, Figure 2. A further noticeable feature is that many crucks have a central ridge purlin which is again fairly ubiquitous on box framed structures of our region, see figure 1, and fits with the geographical distribution. Note that no ridge purlin exists with the clasped purlin roof at the Commandery.

Figure 2 Cutaway drawing of the Commandery, Worcester © Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service: Charles Archive Collection.

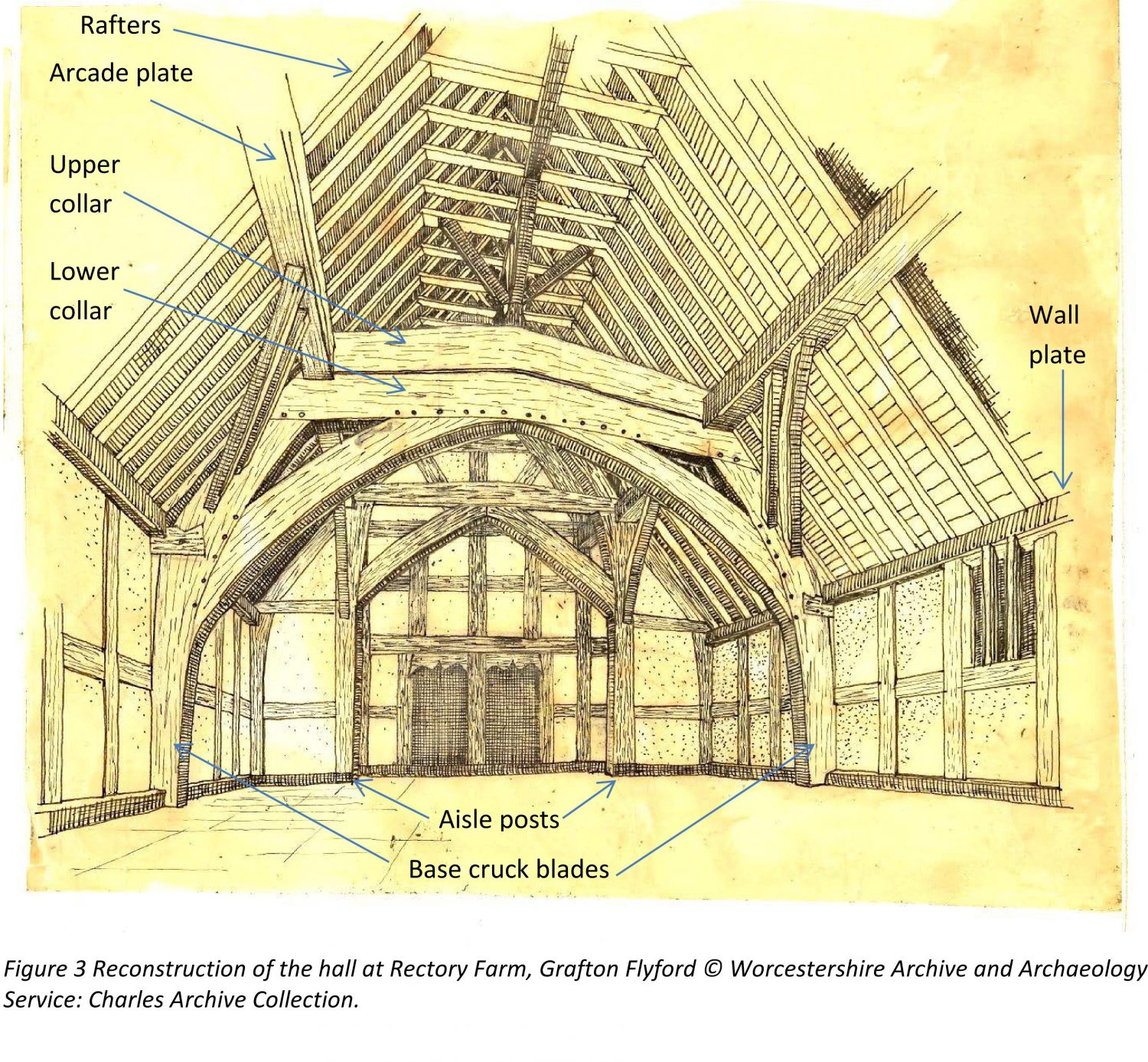

A further variation on the “true cruck” is the “base cruck” which had a relatively short span of use from around 1250 to 1350. This was an amalgam of cruck and aisled building forms. The base cruck again started at floor or cill wall level but extended only to mid-way up the roof to support an arcade plate (see diagram below). It is noticeable from Charles’ reconstruction of the hall at Rectory Farm, Grafton Flyford, Figure 3, that this arcade plate runs directly into an cross frame constructed with aisle posts. Aisle post constructed buildings are demonstrably archaic, with numerous examples existing in the archaeological record from the prehistoric period onwards.

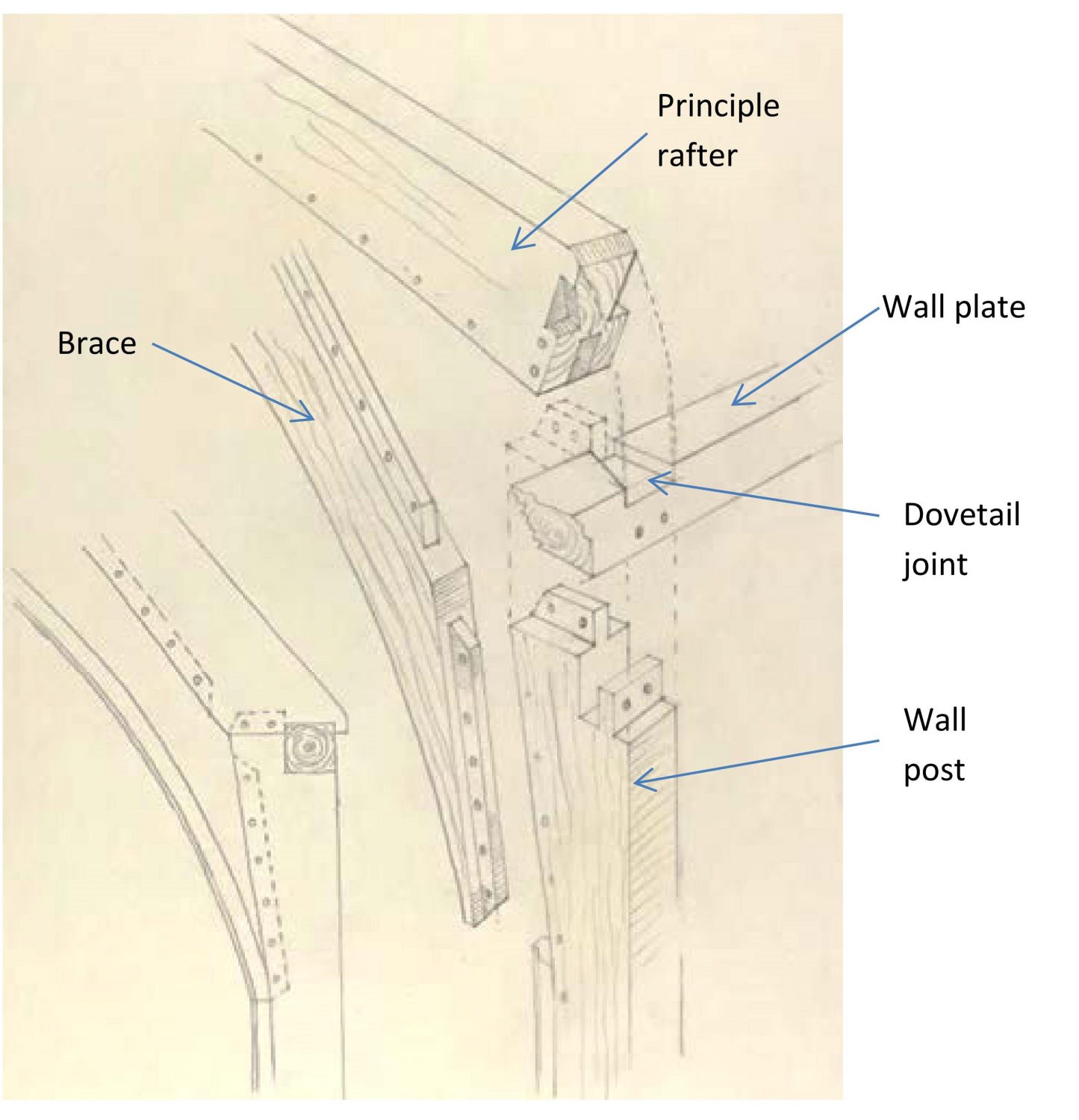

An unusual feature of base cruck trusses is the double collar, which seems unnecessary. Charles suggests though that the upper collar has the critical role of anchoring the arcade plate and preventing its rotation under the weight of the rafters and roof coverings above; much the same as a tie beam in a box framed building. Another similarity is that tie beams of box framed building are jointed to the wall plates by a dovetail joint, as is the case on the upper collar of base crucks. Such a dovetail can also be seen on the base of a principle rafter jointing a “jointed cruck” at 31-35 High Street, Droitwich, Figure 4.

Figure 4 Two dimensional illustration of a “jointed cruck” with a three dimensional blown out illustration above, from Stephens 31-35 High Street, Droitwich © Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service: Charles Archive Collection.

So whilst Charles’ suggestion that the cruck form was archaic remains as yet unproven, his drawings make it clear that he was a diligent observer of medieval and later construction techniques. Along with a detailed knowledge of structural process and a career focussed on timber buildings, he was in a unique position to outline the influence of the details of cruck construction on the timber framing of Worcestershire and beyond. His pioneering views and research remain important in understanding the timber built architecture of the region for all levels of researchers.

References

Hill, N 2005 On the origin of crucks: an Innocent notion, Vernacular Architecture Volume 36

Moran, M 2003 Vernacular Buildings of Shropshire

Charles, F W B 1967 Medieval Cruck Building and its Derivatives

Charles, F W B and Charles, M 1984 Conservation of Timber Buildings

Alcock, N and Miles, D 2013 The medieval Peasant House in Midland England

Post a Comment