Discovering Ice Age Worcestershire

- 22nd October 2018

As earth’s deep history and the evolution of species began to be debated and slowly accepted, researchers within Worcestershire started to investigate the particular history and geology of this region.

Some of the first to do so were Hugh and Catherine Strickland. During the mid-19th century, they discovered the remains of ancient animals, including mammoth, hippopotamus and elephant, around the River Avon and further afield. Inspired in part by the Stricklands, leading geologist Rev. William Symonds conducted fossil-hunting expeditions along the River Severn, wrote a guide for young naturalists and set up Malvern Naturalists’ Field Club and the Woolhope Club of Herefordshire.

Many of the earliest stone tools to arrive in Worcester’s collections came from key sites in France that were excavated in the mid-19th century: St Acheul, Le Moustier, and Aurignac. These tools were found in cave deposits containing the remains of extinct creatures, proving that humans had lived alongside Ice Age animals.

Despite earlier discoveries of ancient animals, by the Stricklands and others, it was not until the early 20th century that the first traces of Ice Age humans in Worcestershire were identified. In January 1915, news of the first Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) artefacts discovered in Worcestershire was announced in a lecture by W. H. Edwards.

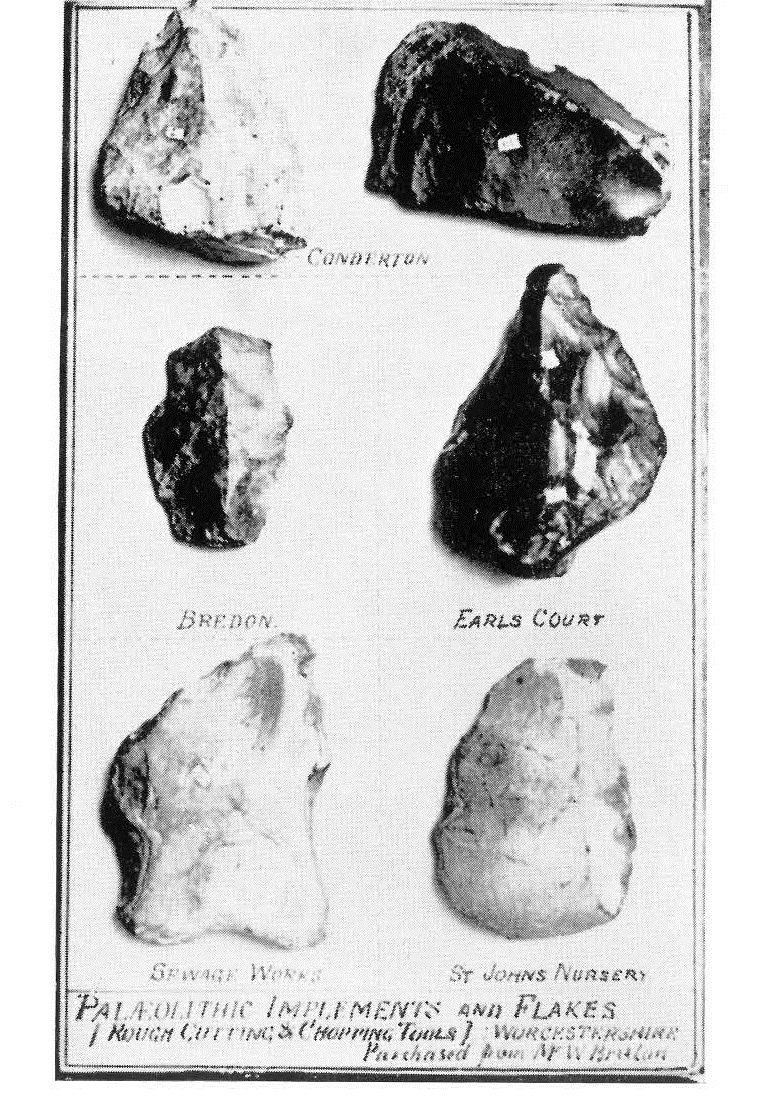

Contemporary image of worked flints found by William Bruton, displayed on W.H. Edwards’ handwritten board

They were found – not by professors or learned gentlemen – but by a tailor from St Johns, Worcester, called William Bruton. Many of his finds were made close to his home in St Johns, in the soils of the extensive plant nurseries. Others came from further afield: Bruton recognised the significance of Bredon Hill to early humans, and made a number of discoveries around Conderton.

W.H. Edwards was the curator of Worcester Museum in the early years of the 20th century, before moving to Birmingham Museum. Edwards recognised the significance of Bruton’s collection of prehistoric stone tools. He acquired many of them, and carefully arranged and labelled each one.

Artefacts from Worcestershire were featured in an influential 1922 paper by Reginald Smith. They caused great excitement. Up until then it had been thought that Palaeolithic artefacts were only to be found in deposits to the southeast of a line running from the Bristol Channel to the Wash. Smith included a handaxe found at Henwick Pit, close to the eastern entrance to the University of Worcester’s St Johns campus.

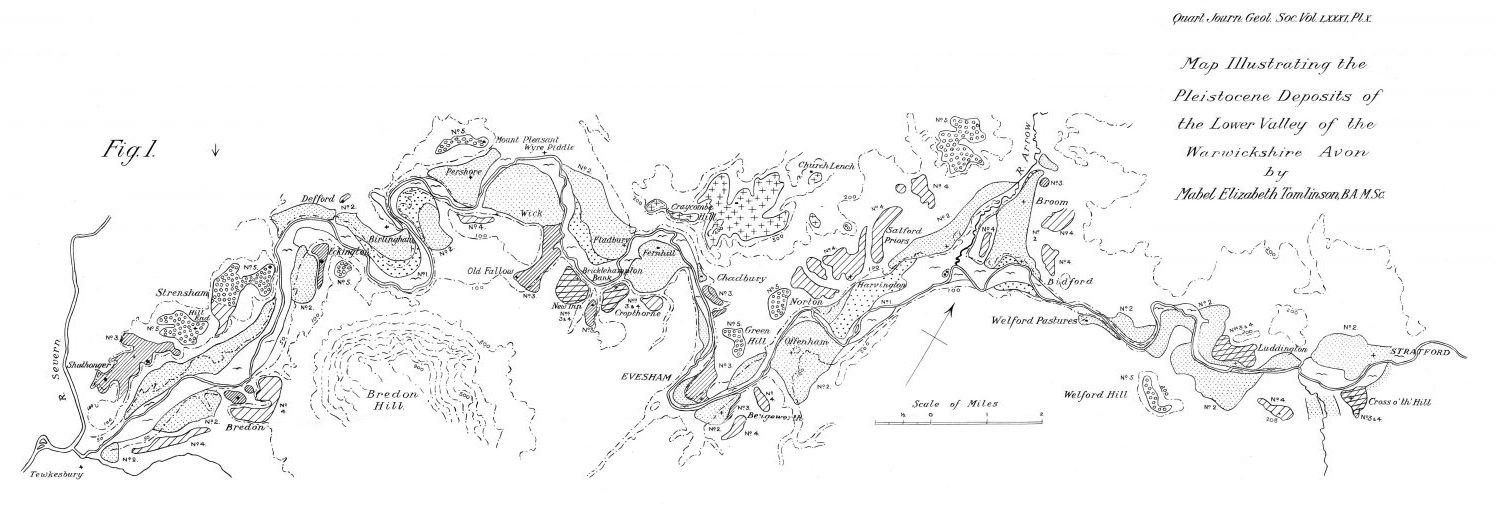

Alongside Bruton’s discoveries, we owe a lot to the work of Dr Mabel Tomlinson for deciphering the Ice Age gravel terraces of the River Avon in Warwickshire and South Worcestershire. After a first degree in Combined Arts, Tomlinson went on to gain a second degree, in Geology, and followed this with a master’s degree, doctorate and higher doctorate. She carried out her research in the 1920s and 30s, setting out from Birmingham to tour the Vale of Evesham on her bicycle, mapping the landscape as she went.

Tomlinson’s map of ‘Pleistocene Deposits of the Lower Valley of the Warwickshire Avon’

Tomlinson also published the discovery of some impressive mammoth and woolly rhinoceros remains within the Vale of Evesham. In her clear, concise style, accompanied by beautiful illustrations, she revolutionised our understanding of this region.

All of this was undertaken alongside her teaching career. ‘Doc Tom’, as she known to her pupils, was an inspirational teacher. She taught at Yardley Grammar School for 42 years from 1917. Her influence was profound: she taught a generation of geologists who have gone on to become leading figures in their field.

Dr. Mabel Tomlinson (‘Doc Tom’)

Further evidence of Ice Age landscapes continues to come to light – in May 2018, a mammoth radius (lower forelimb – see photo below) was reported to Worcestershire Archive & Archaeology Service during our regular monitoring work in Tarmac’s Whitemoor Haye Quarry, and in June fragments of mammoth tusk were identified.

In 2013, Historic England funded a project to bring together all records of Ice Age deposits, finds, and artefacts from Worcestershire. The results were then fed into the Historic Environment Record (HER), a countywide digital database of all archaeological finds and significant locations. This made many publicly accessible for the first time, and ensured they are considered during the archaeological checks that form part of the planning system.

Because evidence is so scarce, this is a field where a single find can change everything. Many of the most significant finds – especially stone tools – are made by keen-eyed members of the public. If you think you’ve discovered something, you can report your find to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, where it will be recorded and added to a national database.

Find out more at finds.org.uk

More is waiting to be found: proximal (elbow) end of a mammoth radius, found in May 2018 – 50cm scale

Post a Comment