Reconstructing Lost Landscapes

- 26th October 2018

How can we visualise lost landscapes?

We start with the evidence. Scientific dating techniques and geological deposit mapping help us to work out how the hills and rivers changed over time – this gives us the basic lie of the land. The bones of large mammals can then tell us which species inhabited the landscape, which also gives us a general idea about the vegetation that might have grown. Below is a reconstruction of Neanderthals hunting reindeer at Kemerton, just over 40,000 years ago. In order to produce this image, illustrator Steve Rigby drew on the discovery of hundreds of bone fragments and stone tools found around Bredon Hill.

Neanderthal hunters at Kemerton, Bredon Hill (by WAAS illustrator)

Geological deposits and animal bones are valuable clues, but how can we find out exactly what type of vegetation and plants grew? Microscopic plant remains, especially pollen, and the remains of tiny creatures can provide astonishing details about the immediate area: the abundance or absence of trees and whether bodies of water were still or fast-flowing. Unlike larger animals, many species of insects and snails are adapted to live in very niche, specific habitats. Identifying which of these tiny species were present gives us a much more precise picture of the immediate environment.

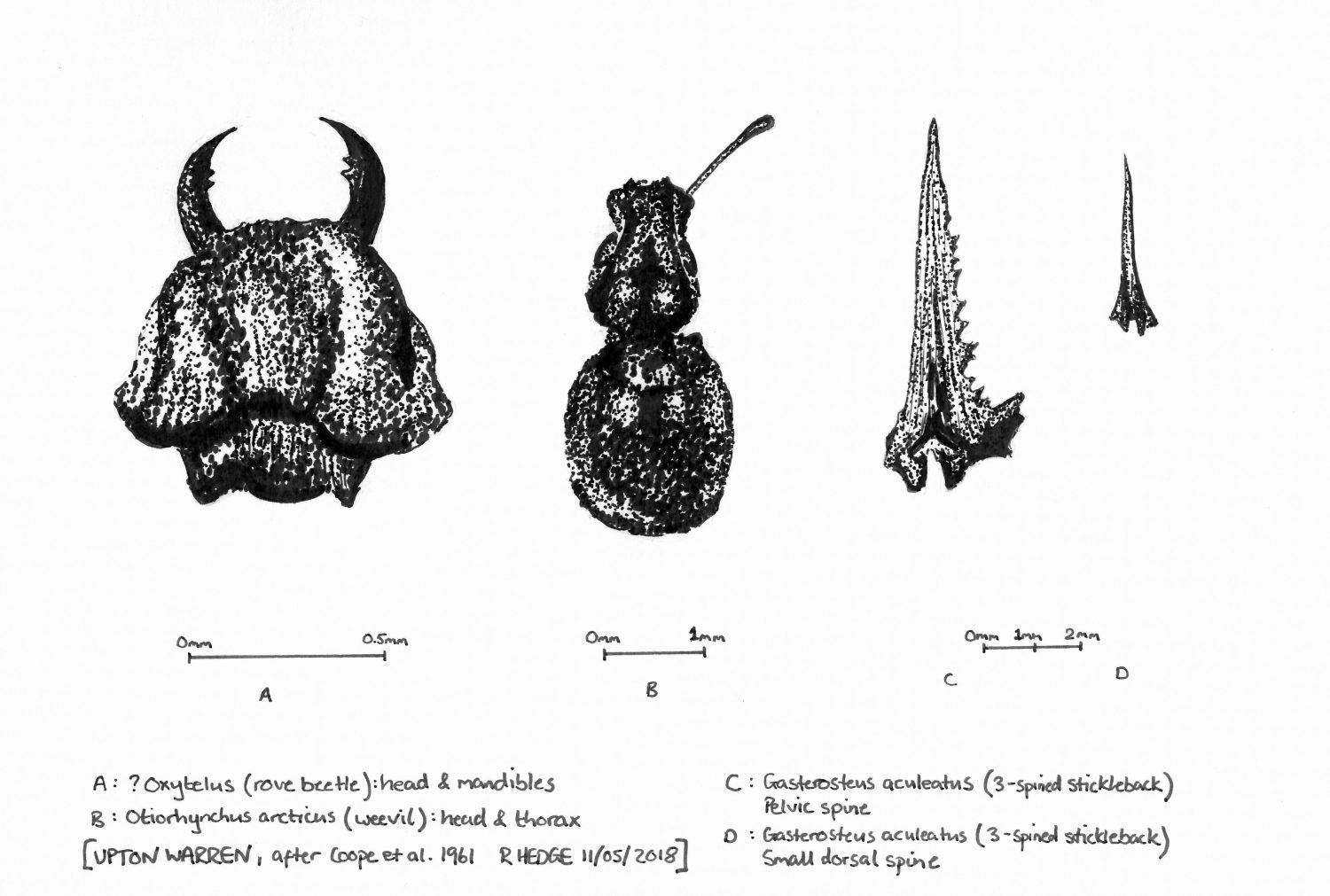

80,000 years ago, the lakes at Upton Warren, Wychbold, were still, salty pools. Woolly mammoth, reindeer, and bison came to drink. Silted up and buried for tens of thousands of years, the site was uncovered by gravel extraction in the 1950s. The miniscule remains of insects and fish from Upton Warren were discovered thanks to painstaking sieving of 600kg of mud. Amazingly, 80,000 years after they were buried, the insects still shone as they emerged from the mud. Researchers carefully noted the colours before the specimens dried and faded.

80,000 year old insect remains from Upton Warren sailing lake and nature reserve

Similar analysis of the sediments around Millicent, a young adult mammoth discovered during the construction of Strensham Services on the M5, revealed cold-adverse mollusc species. Mammoths tend to conjure up images of snowy barren tundra, but as these temperate snails showed, large mammals can live in a relatively broad range of environments – they are not the most helpful indicators for reconstructing lost landscapes.

Alongside Millicent and the cold-adverse molluscs were pollen grains trapped within the silty sediments. Plants produce pollen of different shapes and sizes, making it possible to identify which species they come from. Due to the small, dense nature of pollen grains and their hard surface, pollen can survive in the ground for thousands of years. Careful analysis of the sediments found at Strensham Services revealed evidence of an open and relatively dry grassland with a few shrubs and trees: 200,000 years before the motorway was built, daises, pinks, buttercups, pine, birch and oak grew. Living in this open grassland and temperate climate, similar to today, were mammoths and red deer.

Mammoths at Strensham 200,000 years ago © Pighill Reconstruction (opens in a new tab) – click and drag to pan around the landscape

In addition to the topography, flora and fauna of lost landscapes we can add another layer – human activity. As organic materials soon rot away, stone tools are our primary evidence for the presence or absence of human activity. Stone tools also offer an insight into the technology our early ancestors used and activities they undertook: what type of animals did they hunt and how? Combine these strands of evidence together and Worcestershire’s long-lost landscapes start to come to life.

Thanks for sharing this interesting post.