Before Cathedral Square: Dig Lich Street

- 2nd November 2018

All analysis of the Cathedral Square excavation is now finished and a report has been produced. As the report is very long and technical, we thought we’d summarise our results here too. The Dig Lich Street blog is also still available.

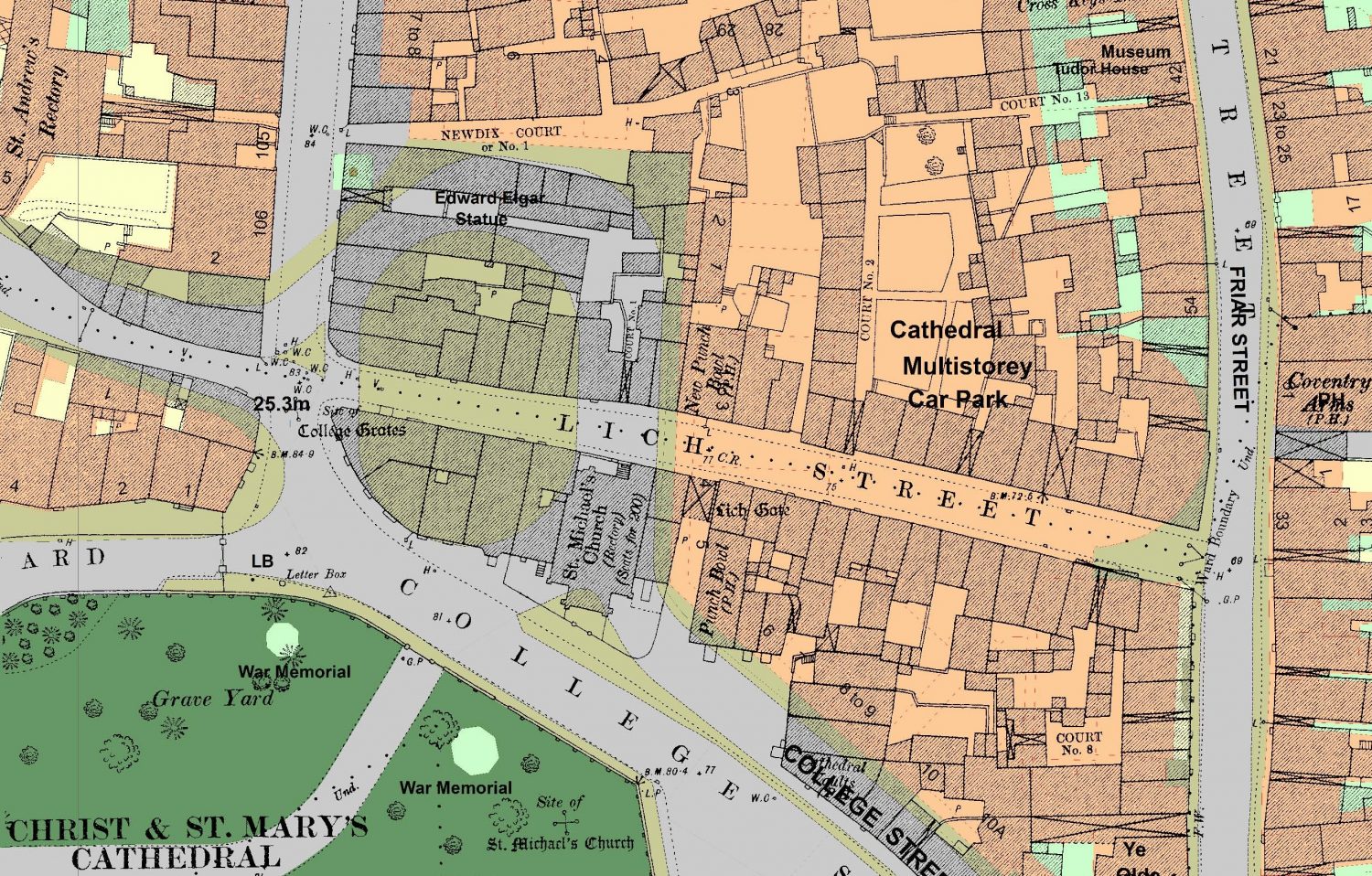

In 2015, an archaeological dig took place prior to the Cathedral Square redevelopment. Our excavation area was confined to the former roundabout, at the junction of High Street and College Street. This site lies east of the River Severn on a gravel ridge, along which the historic core of Worcester grew. Prehistoric and Roman activity is known have taken place in this area, as well as medieval and later buildings. Records show that the southern half of the roundabout formerly lay within the medieval cathedral precinct and was later built over by properties fronting on to College Street and Lich Street.

1886 Ordnance Survey of Worcester, overlain with coloured layout of city in 2015 – yellow oval corresponds to roundabout (excavation area)

Once the four month excavation had finished, finds were washed, identified and analysed. Extensive research into Lich Street’s historic residents was carried out by local historian, Pat Hughes, and the recorded archaeological layers unpicked. Completing each element and pulling these strands together has taken a long time and a lot of work. But the story is finally ready to be told.

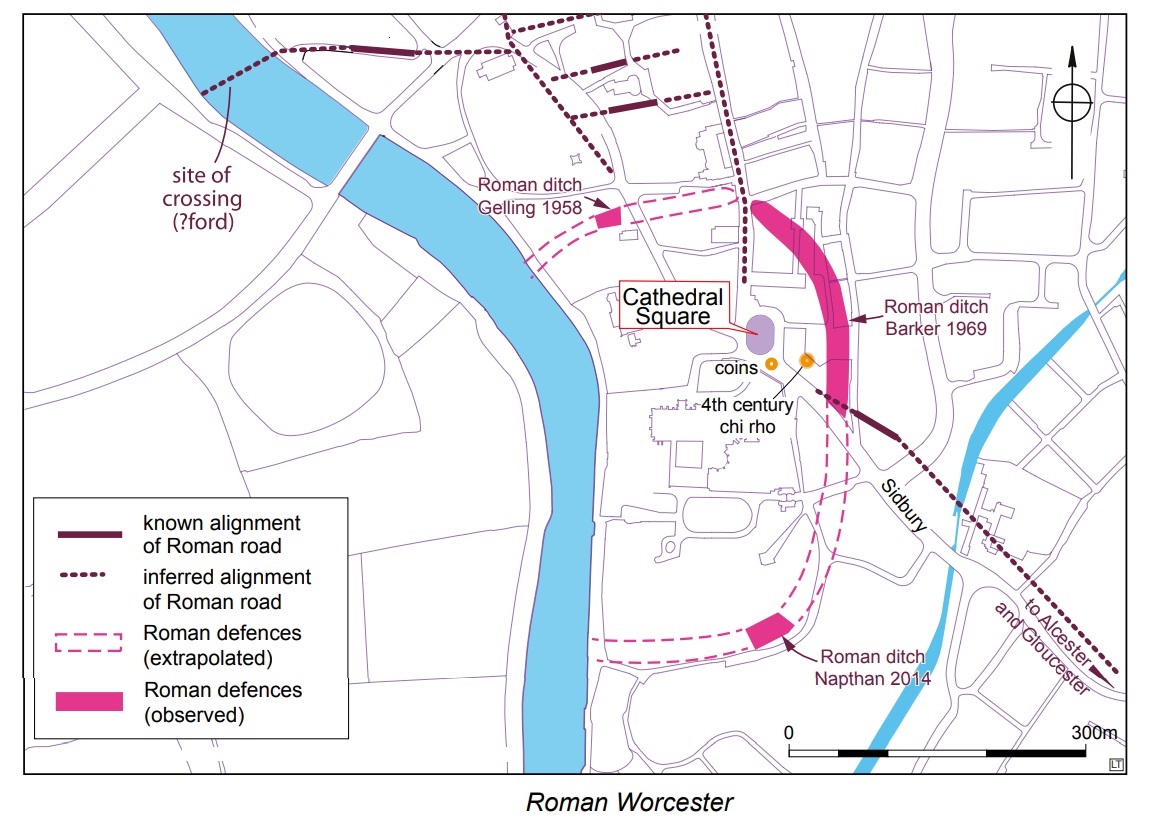

Roman Worcester

Beneath cellar walls, glimpses of Roman Worcester were seen. These layers were only visible in small areas, but are significant for proving that Roman archaeology is preserved below later occupation, despite being truncation by cellars and building foundations. Pottery, tile and iron slag (metal working waste) dating to the 2nd century AD were found within these deposits: tantalising hints of occupation and iron working, which was one of Roman Worcester’s key industries.

Map of Roman Worcester ©WAAS

Anglo-Saxons

Evidence of Saxon Worcester is elusive. Their buildings were primarily timber and leave only a light trace, whilst an apparent preference for using organic materials over pottery means that comparatively little rubbish survives to be found. In total, three fragments of late Saxon pottery were found during the excavation – all had been moved from their original location by later ground disturbance.

Medieval town

Worcester Cathedral, as it presently stands, is thought to have been started in 1084. Until the Dissolution in 1540, the site was a monastery surrounded by an extensive walled precinct and cemetery. The southern half of the excavation site fell within the cemetery, in an area reserved for lay people (non-ordained members of the religious community). Soil deposits in this location were found to contain disarticulated human remains, as well as grave cuts with in situ bone – these were recorded but left interred.

The medieval graveyard deposits were truncated by a red sandstone wall, constructed upon a rough foundation of large green sandstone blocks. Pottery recovered from the backfill of the wall’s construction cut dated from c late 11th to early 14th century, and a series of 15th to 16th century deposits had formed against the wall.

This fragment of wall is a surviving element of the first residential structures to encroach onto the cemetery. These tenements are thought to date from the 13th century and were built along the commercial frontage of Lich Street by the Cathedral to generate rent income. Documentary research revealed that in 1359 ‘a house with 4 shops at the end of the High Street… extending from the said stairs of the cemetery [College Grates] towards the Lychgate’ was leased to John the Goldsmith. Twenty six years later, he sublet some of the property to William More, his wife Agnes and son John.

As goldsmith suggests, Lich Street was a relatively high status area adjoining the Cathedral: the most important building in medieval Worcester. Whilst few early records survive, it appears that the south (cemetery) side of Lich Street was mostly built up by the mid-15th century.

Medieval sandstone wall discovered during excavation (1m scale)

Late medieval and post-medieval development

At least one of the 15th century properties is described as a timber framed building – highlighting one reason why little remains of the earliest houses along Lich Street. Many of the surviving stone and brick buildings on site are likely to have been constructed in the late medieval and post-medieval era, with subsequently repair work, extensions and rebuilding continuing into the 20th century.

Several wall foundations were constructed of (probably reused) sandstone. Further sections of early wall, preserved in pockets beneath or within later redevelopment, dated to the post-medieval era; probably the 17th or 18th century. One complete early cellar did survive in the south-east corner of the site. Built primarily of re-used medieval sandstone and church masonry, interspersed with brick and tile levelling layers of 15th to 18th century origin, the cellar also contained additional structural elements that had 17th to 18th century pottery in the wall infill.

Wall containing a reused stone, possibly from the Cathedral or a nearby church (30cm scale)

Alongside building activity, a large pit in the yard of No. 5 Lich Street also dated to the 17th-18th centuries. Tin-glazed ware, part of a pancheon (large shallow bowl), glass flask and Frechen jug were found within the pit. All are 16th to 18th century in date and some were undoubtedly imported from the continent. During the 16th century, No. 5 Lich Street and No. 2 High Street were owned by John and Elizabeth Parton. Intriguingly, a 1574 probate inventory of items left by Elizabeth includes a large number of ‘pots’ in her kitchen and luxury goods in the shop: are these the high status vessels found in the pit?

Pottery (back) and glass vessels (front) from a pit in the yard of No. 5 Lich Street

Modern re-development

Most phases of building work dated to the 19th and earlier 20th centuries. Cellars were located below at least thirteen demolished buildings along Lich Street and College Street, and several had external yard areas. In addition to numerous repairs, sub-divisions of rooms showed how the properties became more densely occupied over time. Fireplaces in several cellars suggest these spaces were turned from storage areas into living quarters, as the status of the area declined.

Stairs down into the cellar of No. 3 College Street

Demolition deposits from the area being levelled in the mid-20th century had infilled all the cellars, and some hardcore survived from the site being used as a car park in the 1960s. In amongst this demolition and made ground material were architectural fragments that appeared to have come from St Michael’s Church, which previously existed immediately east of the site.

Reinstatement and preservation in situ

The project was designed to preserve important archaeological remains in situ. Throughout the site, the depth of excavation was dictated by the development’s impact level. Many features were identified below the construction level of the new road and public square; only the uppermost surfaces and the top of walls were removed. As such, much of the site could be preserved in the ground without the need for further excavation. Floors were kept intact and covered with a layer of sand, before cellar walls were protected with boarding and polythene sheeting and foam concrete poured in. Most of the archaeology excavated, and the earlier Roman activity glimpsed below cellars, survives for future investigations.

Protecting and filling in the cellars before construction work took place

If you would like to find out more, a short booklet covering the excavation and archival research will shortly be available from The Hive. Further details are also given in the report: Bradley, R. 2017 Archaeological Investigations at Cathedral Square, Worcester. Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report No.9

Documentary research was carried out at Worcester Cathedral Library and Worcestershire Archive & Archaeology Service – references to original documents can be found in the report.

Very clear report summary. Good to see the history and to know some is preserved for the future.