Pets in the Archives

- 23rd November 2018

As today’s theme is #archiveanimals this blog will look briefly at the history of the animals in our homes, our pets, and the special place they have held in our hearts for centuries through some of our documents here at the Hive.

| As today’s theme is #archiveanimals this blog will look briefly at the history of the animals in our homes, our pets, and the special place they have held in our hearts for centuries. Keeping animals however purely for the sake of companionship is a relatively recent social development, becoming particularly important from the 18th century. The earliest use of the word pet in the Oxford English Dictionary dates is from 1539 and relates to the hand rearing of lambs in the home, which therefore implied a favoured position in the domestic space. By the 19th century this term had expanded to include other animals which were increasing being invited into the home.

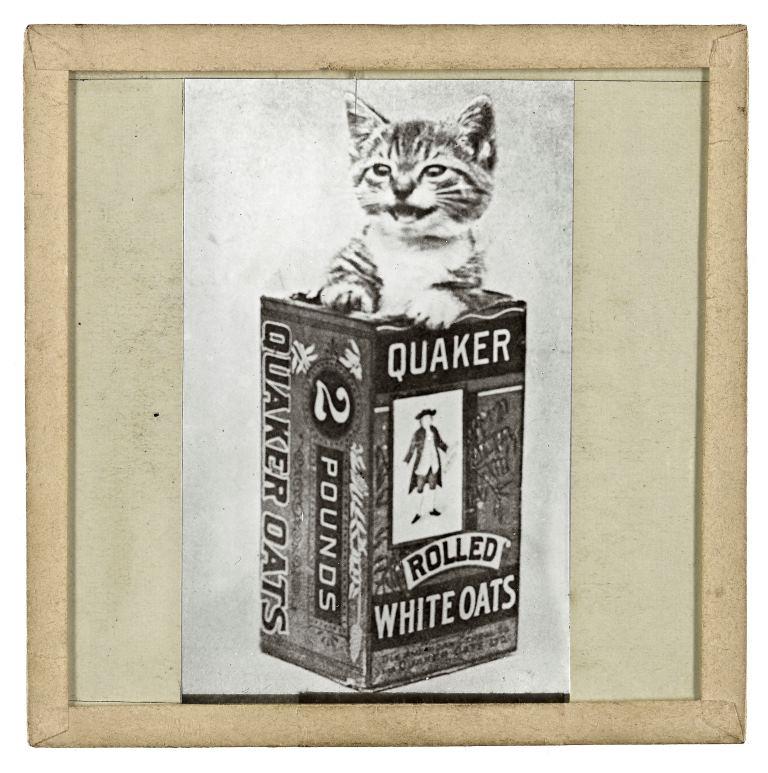

Ingrid Tague (2008) in looking that the characteristics of pet ownership and the development of this in the 18th century states that ,’pets have two defining characteristics: they live in the domestic space, and their primary purpose for humans is entertainment and emotional companionship’. Alongside the sharing of the space designated as human she argues it is the disposable income required to keep animals, which are not working or providing food for us which makes pet ownership distinctive. The growth in the economy and related consumer industries in the 18th century let to a more wide spread ability to keep animals as pets.  Reproduced from original Whinfield lantern slide collection, courtesy of Worcester Diocesan Church House Trust

A couple of letters in the Croome collection here at the Hive hold letters relating to puppies as pets for the Countess of Coventry. Although these are spaniels which may have also had a role as gun dogs in hunting they certainly held the position of pet in the Coventry household as can be seen in this description below of the puppy being in the Countesses private chambers and describing the character of the dog as entertaining.

“My Dear Lord, I have sent the puppy according to your directions and I shall think myself very unfortunate if it does not prove to Lady Coventry’s fancy – I could have sent ones much larger from the same litter but I particularly chose this as best suited for her Ladyships purpose for I am already so well acquainted with his merits and entertaining mischiefs that I shall not despair of seeing him in possession of a good birth in Lady Coventry’s own dressing room. Having now acquitted myself with the regard to the little animal, I should release you; if I did not think it incumbent on me to thank you in the best manner I can for the kind instructions you were so good to give me to guard against the consequences of my amours;….” 705:73 BA 14450/288/15(7) Croome Collection

In this late 18th century or early 19th century letter the author seems to give a puppy as a gift in thanks for advice from the George William Coventry the 6th Earl of Coventry. This was written from Middleton Park which was the seat of the Earls of Jersey. This could be from the Earl of Jersey who in the late 18th century was George Bussey Villiers the 4th Earl. However the signature is not clear and looks more like an F than a G which could actually make the puppy a gift from Francis Villiers, née Tywsden, the Countess of Jersey, who was famous as a socialite and the mistress of the Prince regent (later George IV) in the 1790’s. Unfortunately this letter is undated so it is not clear when exactly this was sent. The value of the pet is clearly quite high at a time when social indiscretion could have ruined the author and thus is given in exchange for valuable advice.

Another letter from Lady Rockingham to the Countess of Coventry, Barbara St. John describes the trade of specific breeds of dog. She offers a puppy from one of her own dogs in exchange for a dog Lady Coventry had given to her and the particular preference of Lady Coventry for red and white spaniels over black and white

“… in return for the very obliging and flattering manner in which Ly Coventry was so good as to relinquish the other like dog, she may depend upon Ly Rm Begin affective to the earliest opportunity in her power of presenting her Ladys With a whelp of her own breed of spaniel, and begs to know whether she is right in supposing that no colour but red and white would be acceptable…” 705:73 BA 14450/287/11(4) Croome Collection

This trade highlights what Sarah Amato (2015) calls the ‘commodity state’ of pet ownership where the pet becomes, by the end of the 19th century, a ‘mass consumerist enterprise’. She argues that’ the possession of a pet involved simultaneous imperatives of love, companionship, moral enhancement, utility, discipline, abuse, investment, and profit’ which provides a more complex view of pet ownership.

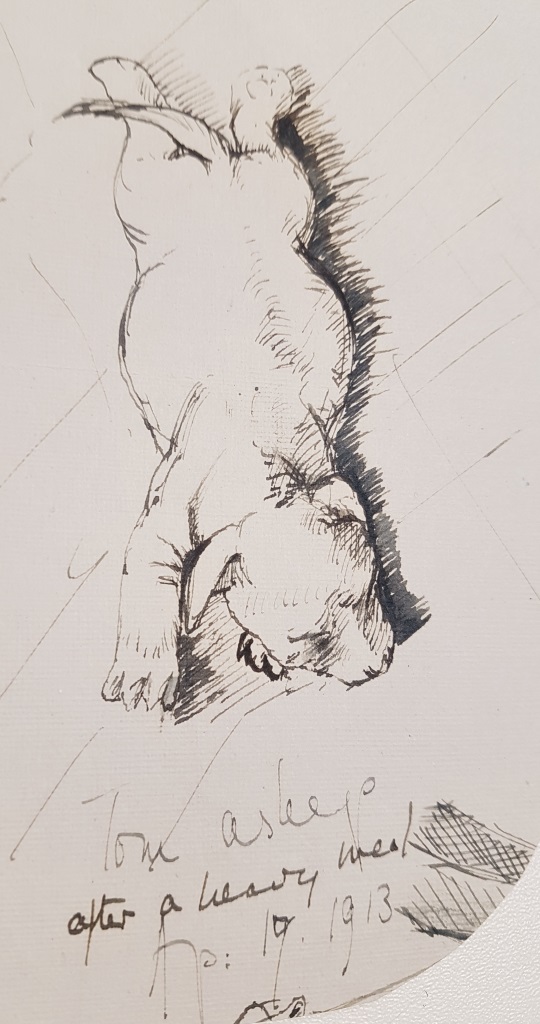

In the early 20th another letter this time in the collections of the Lyttelton family written in 1913 from Maud Wyndham née Lyttelton in South Africa to her mother, includes a drawing of one of the puppies named Tom, whose brothers she mentions where known as Dick and Harry.  ‘Picture Tom asleep after a heavy meal Ap:19 1913’ Reproduced from the Lyttelton Collection Courtesy of Lord Cobham

As pets became an important part of the household their loss was often keenly felt. Ingrid Tague (2008) explores the growth of literary culture in the 18th and 19thcenturies and the phenomenon of writing elegies to dead pets as people began to mourn the animals which had become in many cases like family members. In May 1812 on the death of one of the families dogs, the Earl of Coventry following this tradition of eulogising pets, commissions a poem for his spaniel, Tray who although one of his hunting dogs is described as his ‘faithful friend’ and the poem promises never to forget him. ” The Dying Spaniel

In sorrow dear Tray I visit thy bed; In sorrow they weakness disclose; Poor Fellow thou liftest thy languishing head To look on thy master once more …… Think not with this life that thy mem’ry will end Til mem’ry shall vanish from me; I ne’er can forget a faithful old friend and that faithful old friend will be thee

Whene’er at our club brother sportsmen I join Who the power of their spaniels display, The province so pleasing shall always be mine To dwell on the merits of Tray.”

705:73 BA 14450/358/5(8)

In these archival examples we can see the special relationships we have long had with our pets and emotional attachments which can be found in the records. |

| Amato, Sarah (2015) ‘The Social Lives of Pets’ in Beastly Possessions: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture. University of Toronto, pp.22-23

Tague, Ingrid H. (2008) ‘Dead Pets: Satire and Sentiment in British Elegies and Epitaphs for Animals’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 41, No.3 (Spring, 2008) p.290 |

Post a Comment