Ruardean Castle Excavations

- 26th November 2018

Ruardean Castle, in the Forest of Dean, is a nationally important site. Despite this, relatively little is known about it – when was it first built and occupied until? Did it start life as a motte and bailey castle or ringwork (defensive site protected by a ditch and bank), and when was it converted to a fortified manor house?

Excavations at important sites like Ruardean Castle (legally protected as ‘Scheduled Ancient Monuments‘) are only allowed with permission from Historic England, so it’s not every day you get to excavate a castle. Permission received, at the end of October we ran a community dig at Ruardean Castle as part of the Heritage Lottery Funded Foresters’ Forest Landscape Partnership. So, what did we find?

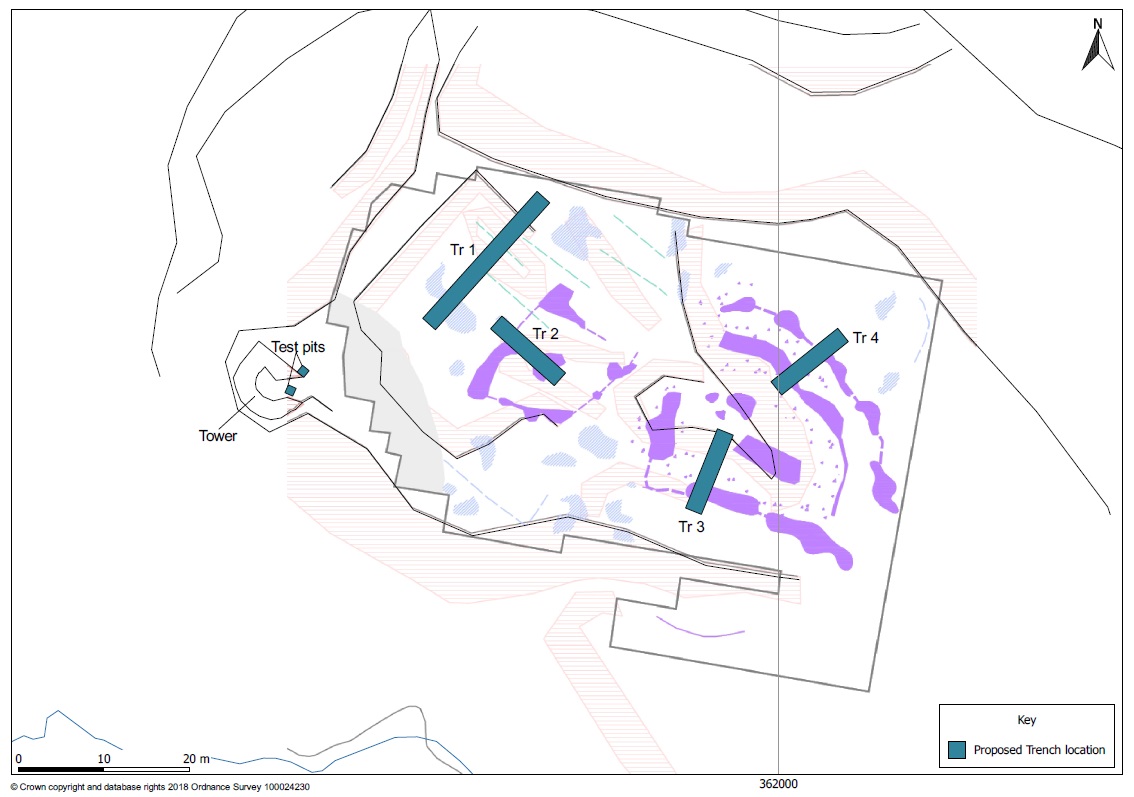

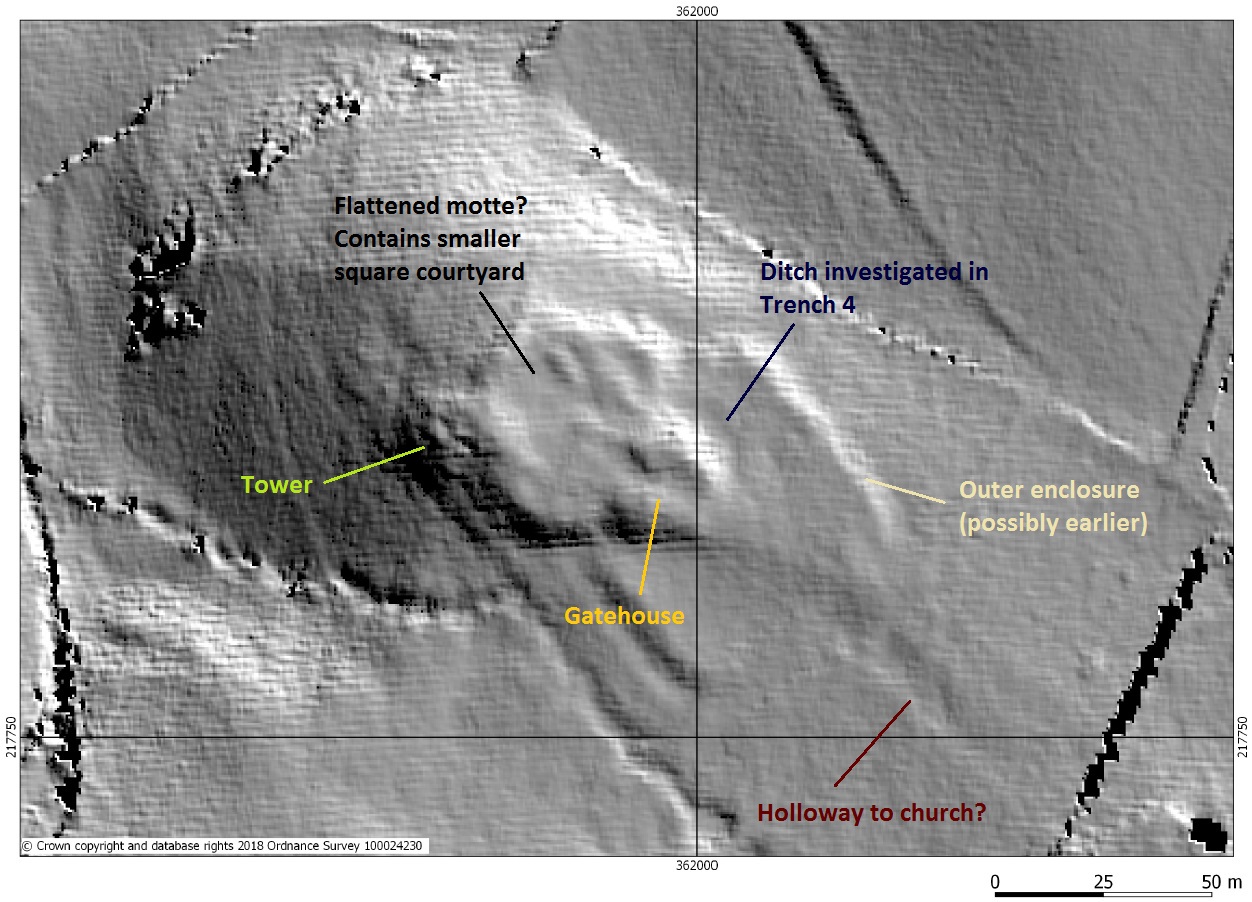

Four trenches and two test pits (1m2) were excavated across the site by a group of wonderful volunteers. Information from geophysical surveys, which detect buried features, and LiDAR imaging, which records even the slightest earthworks, were used to target areas of interest. Ruardean Castle sits on a promontory with a faint trackway running southeast towards the nearby parish church, which dates from the 12th century. Apart from ambiguous earthworks, the only above ground feature to survive is a small section of the stone tower, which we further exposed with two test pits.

Map of trench locations across Ruardean Castle, showing recorded earthworks (red striped areas) and geophysical anomalies (purple) – irregularly boxed area shows the extent of geophysical surveys.

As soon as the grass was removed, stone rubble then walls began to emerge. Trenches 1 and 2 tested a square enclosure, or courtyard, attached to the tower, whilst Trenches 3 and 4 were placed over a possible gatehouse and double ditched outer enclosure. One of the few historic documents relating to Ruardean Castle is a ‘licence to strengthen and crenellate’ (fortify), granted by the crown in 1311 to Alexander de Bykenore. Here, the building is described as a mansion but no specific location within Ruardean is given. It’s widely believed that the area referred to as Ruardean Castle was a small Norman castle later converted into a manor house, which was fortified in the 14th century, but it’s not impossible that the crenellation licence refers to a manor elsewhere in the local area.

Now let’s get back to the archaeology. A nice, well faced wall quickly appeared at the northeast end of Trench 1 (see below). It overlies an earlier wall and was constructed from a mix of limestone, red and green sandstone. No buildings were found against the wall, showing that this was an outer enclosure or curtain wall, rather than a range of courtyard buildings, which re-used stone from earlier structures on the site or nearby. The underlying wall is on a slightly different alignment, implying that this part of the site was not just repaired but remodelled.

Walls exposed in Trench 1 – the large stone on the right may be blocking an older entranceway or be part of adjoining wall

Further west, Trench 1 crossed a second low bank. Excavation demonstrated that this was a mound of stone rubble, possibly from collapsed structures or the robbing of building materials for re-use. Below this mound, keen eyed volunteer Ian Evans spotted a rare find: an antler gaming piece. You can read more about this lovely find in a blog entirely dedicated to it (here), but suffice to say that it was probably made between the 11th to 14th centuries and is similar to other known medieval chess pawns.

Gaming piece found at Ruardean Castle – the oval section on top is a separate plug over the antler’s honeycomb interior

Another fascinating find turned up in Trench 2 – a copper alloy key. This emerged beneath another layer of rubble, which was widespread across the site, and on top of a beaten earth surface. Could this be the key to the castle? Sadly, it is a little small for a door key. It may have been a more personal possession though, as it resembles casket keys made during the medieval era and 16th – 17th centuries. Alongside the earthen surface, a roughly constructed stone wall was found in Trench 2. This is hard to interpret, as only a small section was exposed, but may be part of a building inside the curtain wall.

Trench 2 under excavation as wall emerged and key (insert)

Just beyond the inner courtyard, those working in Trench 3 were rewarded with a glimpse of the gatehouse structure. Two buildings, either side of the entrance, are thought to have formed the gatehouse – Trench 3 appears to have covered the entrance gap and clipped the edge of a stone building. A layer of iron working waste was also found in this trench, which may be a cobbled surface or later dump of waste. Finds dating from the 18th century to present day were found within the topsoil and stone rubble, highlighting how frequently the site has been visited and used – to dump rubbish or as a source of good building stone – since it fell out of use.

Last, but by no means least, we reach Trench 4. Located across geophysical anomalies of a possible double ditch, this trench proved that the outer was not an archaeological feature. The other ditch around the gatehouse was 3m across, but didn’t contain many finds. A second possible, significantly larger enclosure beyond the gatehouse is visible on the LiDAR survey as an earthwork. We didn’t have time to investigate this, but it may be earlier as it’s on a slightly different alignment to the rest of the site.

LiDAR survey of Ruardean Castle with annotations (original image (c) Peter Crow. Forest Research; source, Cambridge University ULM (2006))

The oldest known map of Ruardean, dating from 1608, depicts all buildings as little 3D sketches except for the castle, which is shown in plan as a square courtyard with division (possibly a building) in one corner and two external protrusions – one corresponds with the location of the tower. Due to this difference in illustration, it’s been suggested that the fortified manor was already a ruin by 1608. Finds are still being washed and analysed, so we’ll have to wait a little longer to know for sure, but this seems to broadly fit with our results. Despite later pottery and artefacts being present, these primarily came from the topsoil and rubble layers.

Thanks to our fantastic team of volunteers and staff, the first modern excavation of Ruardean Castle has proved that stone walls, surfaces and medieval finds still survive across the site. Several phases of alterations were visible from the exposed walls, demonstrating that the site was occupied for a long time and at least partially remodelled. Given limits of time and the size of area we had consent to excavate, not all questions could be answered. But we were able to investigate several areas of earthworks and geophysical anomalies (and prove that not all of the latter are archaeological), as well as confirming the presence of a curtain wall that lacked courtyard buildings against the north-eastern side. This may have been similar to Stokesay Castle, in the Welsh Marches, but with a stone gatehouse and one or two outer enclosures.

Thank you to everyone who took part and visited us during the open day or schools day! Ruardean Castle is accessible to visit via public footpath, but please remember to keep to the path as the site is on private land.

Post a Comment