The Charles Archive: Controversial Conservation at The Commandery

- 18th December 2018

This is the nineteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating the life and work of timber-frame building specialists FWB ‘Freddie’ and Mary Charles. Funded by Historic England, the ‘Charles Archive’ project aims to digitise and make more accessible the Charles collection.

The story of The Commandery restoration is rather protracted, one which involves plunging headlong into file upon file of planning history, roll after roll of building surveys and site notes and thousands of megabytes of HER data, including photographs, press cuttings and correspondence. Knowing what a large and complex site this is, I was rather prepared for never finding a true narrative, but rather to be bogged down by the weight of material. However, my research was rewarded by a tale of polarized opinions, gnashing teeth and locked horns. The challenge now is to keep it succinct, though I would recommend a good read of the archive if you ever get the chance!

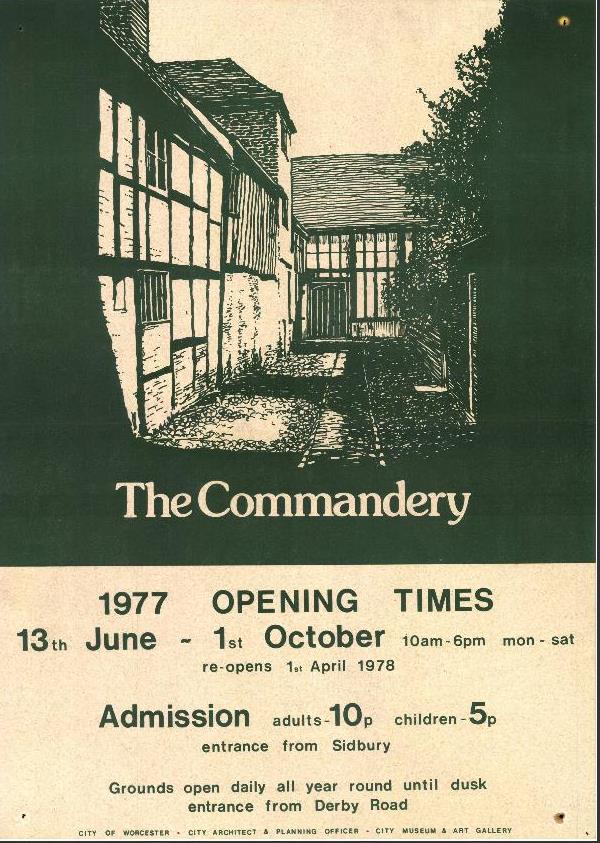

To go back a few years before the Charles practice enter the fray, in 1973 the long-established printing firm Littlebury & Company, finally closed The Commandery doors and shut down their presses. The loss of more than 50 jobs at the site was blamed on the introduction of Value Added Tax and the Worcester Press as it was known, was dissolved. The Littlebury family had been relatively careful and interested custodians of the 1000-year-old site, since its purchase in the late 19th-century and it would seem, were keen to see the historic buildings enter public ownership. After a few months of discussion, press speculation and juggling of budgets, Worcester City Council finally purchased the former Hospital of St Wulstan’s and Civil War HQ on October 4th, 1973 for £180,000. A year later, the Worcester Evening News proclaimed ‘Battle HQ to be given new look’ and reported on a scheme to convert the building into a ‘cultural and leisure centre’, whilst using the building for short term exhibitions, meetings and lectures. Initial works were expected to cost around £128,000 and included demolition of the canalside printworks and kitchen block to the north, reroofing of the 15th-century Great Hall and extensive restoration of the Oriel window. By 1977 the building was officially opened by His Grace The Duke of Hamilton and Brandon.

The Commandery opening times, 1977 (Worcester City Historic Environment Record)

By 1985 it was clear that another large programme of works would be required. At this point Freddie Charles was approved as consultant to oversee restoration works to No 1 Commandery Drive, the Georgian re-fronted, 15th-century solar wing. During these works Freddie was able to corroborate previous research by Nick Molyneux that the solar wing and Great Hall were not just broadly contemporary but had in fact been the subject of a single construction event, such was the design of the build. This phase of works was completed with a good deal of timber replacement and with the removal of a 16th or 17th-century ceiling, though the latter seems to have predated the Charles practice’s involvement. There seems to have been some discussion over the Charles practice approach to conserving the building by taking it back to the predominant building phase and installing 15th-century style windows as a replacement for the Georgian sashes. This proposal was rejected in order to retain more of the historic development of the building.

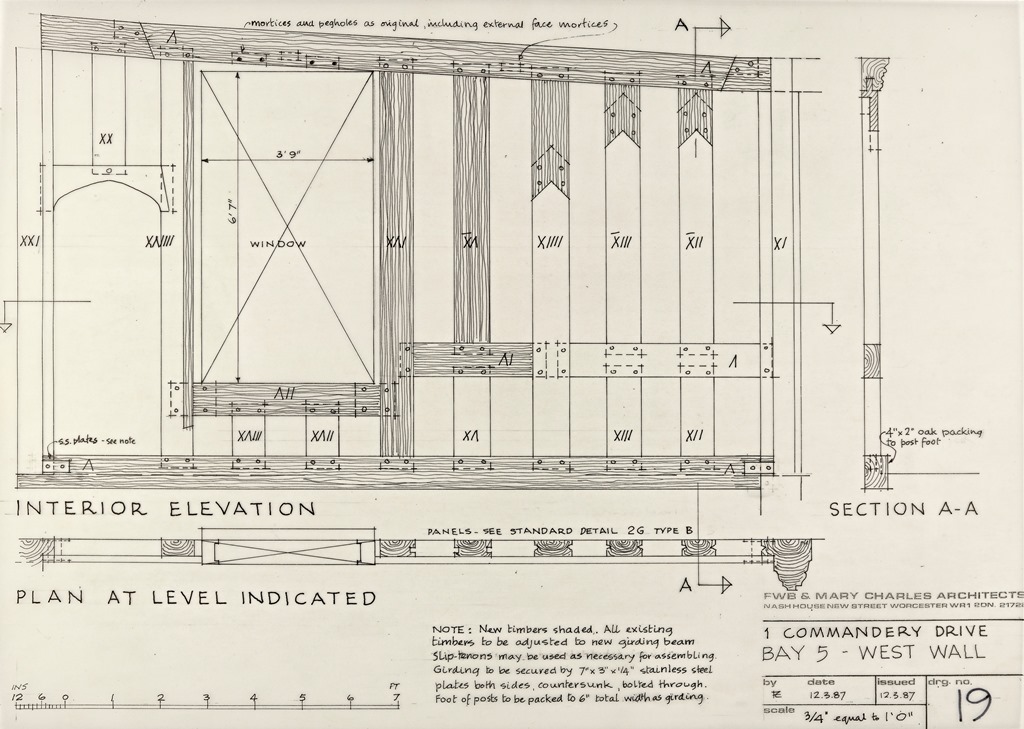

Replacement timber (shown shaded) to the interior elevation of 1 Commandery Drive, 1987 © Worcestershire County Council, Charles Archive BA13218-1-3_11

Works to the canal range in 1988 however, proved to be altogether more contentious…

As has been stated in previous posts, Freddie’s architectural practices are recognised today by other conservation architects and buildings archaeologists alike, as he set the bench mark for both practices, making it a common practice to go out to an historic building, survey and record it, then go back in to detail and survey the problem areas where conservation and restoration is required to enable a conservation strategy to be drawn up.

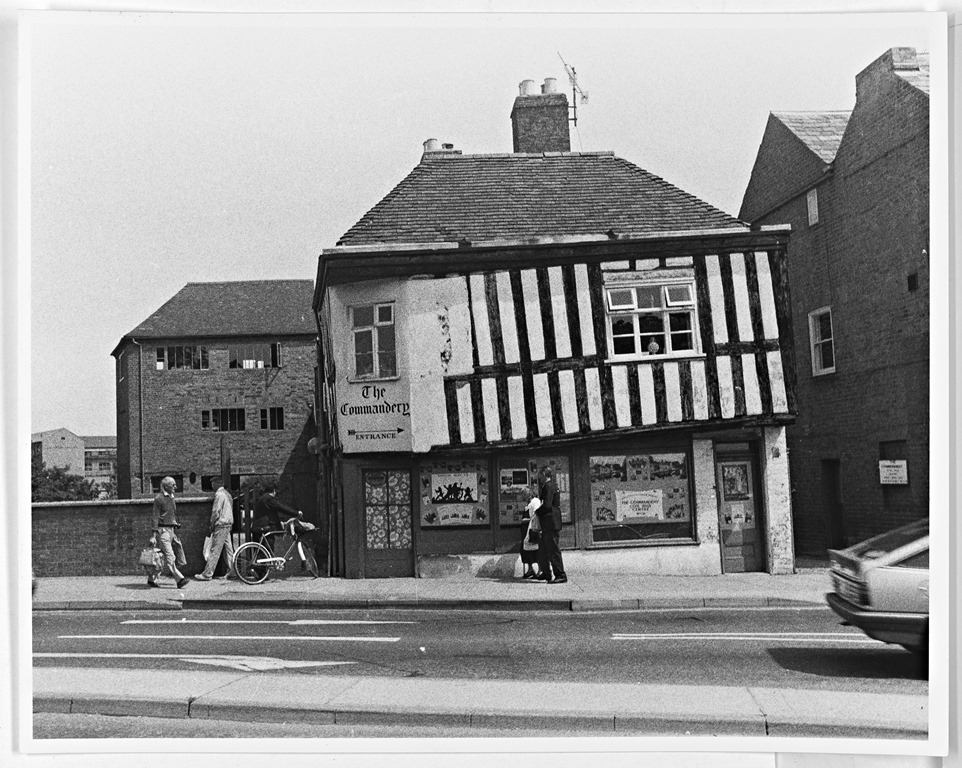

In January 1988, a detailed structural survey report was produced relating to the reconditioning of the Canal Range, including Sidbury shop, workshop and warehouse. This was submitted in support of a Listed Building consent application which stated that the existing building was currently unsafe. Indeed local councillor Geoff Carpenter later commented that “the whole building was resting on a jar of dolly mixtures in a sweet shop”. This new phase of works was to bring the sweet shop and wool shop fronting on to Sidbury, in to use by the museum, giving the complex much more of a public presence.

The canal range and frontage shops had been structurally compromised in the early 19th-century with the building of the canal and locks which run parallel to the site. The long range of buildings running north from the frontage shops had been rapidly shored up and infilled with cheap brick at that time, while the south-west corner of the shop frontage took on a rather slumped appearance that was never fully rectified. By the 1980s, it was clear that radical intervention was required.

View of the Commandery Canal wing towards Sidbury (c1985) (Worcester City Conservation Photograph Collection)

Commandery Sidbury frontage in the 1980s © Worcestershire County Council, Charles Archive BA12857-14-10_01

Freddie’s proposals for the canal side warehouse and workshop were broadly met with approval and passed by the local conservation team and English Heritage inspectors with only minor comment. His vision for the range as seen in the drawing below seems largely to have been as delivered.

Possible Reconstruction of the Commandery Canal Range © Worcestershire County Council, Charles Archive BA12857-14-15_04

Proposals for the frontage shops however, were less popular. Extensive works were required to secure the building which seems to have been in danger of collapse. Freddie applied his distinctive style to the design, proposing that the 19th-century alterations be taken out in favour of a return to the predominantly 16th-century nature of the building. The approach was not universally popular and comments from the then Director of Avoncroft Museum of Buildings echoed the sentiments of many: “Whilst accepting that the structural implications are considerable, we find the proposed loss of the present appearance of the shop is to be deplored. The way in which the building has been altered at various times with the incorporation of sash windows and hipped roofs gives it a charming if somewhat quirky appearance. The proposed reconstruction is charmless and uncompromising.” The Ancient Monuments Society on the other hand merely commented: “Another model FWB Charles Scheme!”.

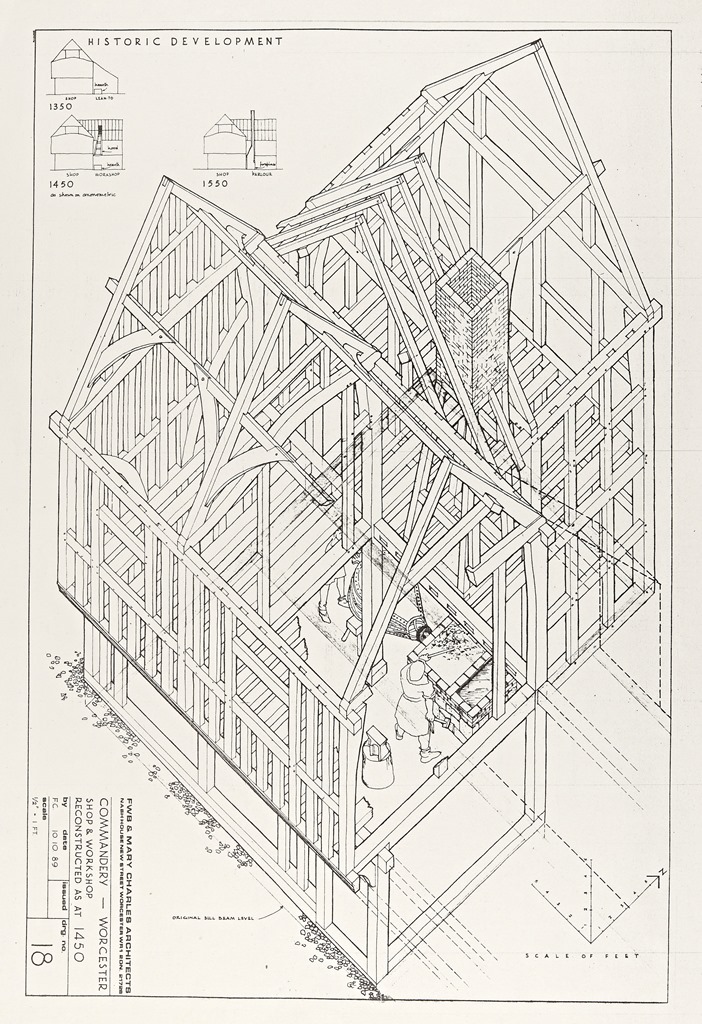

While much of the design was agreed upon, it is during this period that Freddie came in to particular conflict with the Head of Planning at Worcester City Council, Stuart McNidder and a series of letters flowed back and forth. In one such letter to Mr McNidder in June 1988 Freddie’s firmly laid out his stall: “We should not alter its design… for the sake of architectural embellishment… That would be wholly against our method and principle, which is to allow the historical structure to speak and suppress all architectural whims, whether our’s or anybody else’s”. Letters from English Heritage’s Historic Buildings Architect urged that they “resolve the difference of opinion”. Unfortunately, the disagreement continued, and the demolition of a chimney stack on Freddie’s order (without Listed Building consent) caused particular bad feeling. Freddie insisted that this was necessary to repair the joists to bay 1 (the workshop) though English Heritage demanded that this must be reinstated, something which he was very loathe to do. The situation dragged out for many months while the case was argued, until finally further research undertaken by the Charles practice provided them with the evidence to ensure that they wouldn’t after all be compromising their principles, and the stack was rebuilt.

Historic reconstruction of shop and workshop (1450), with the contentious chimney stack illustrated © Worcestershire County Council, Charles Archive BA12857-14-14_02

The resulting work while controversial to many, has ensured that the Commandery museum has remained as a well-used and well-loved landmark of the city and should continue to be so for many years to come.

Before and After

This is a guest blog by Sheena Payne-Lunn, Historic Environment Record Officer for Worcester City Council, who has been working with us on the project.

![]()

Post a Comment