The Charles Archive: The Freddie Charles Method

- 27th December 2018

This is the twentieth in a series of blog posts celebrating the life and work of timber-frame building specialists F.W.B ‘Freddie’ and Mary Charles. Funded by Historic England, the ‘Charles Archive’ project aims to digitise and make more accessible the Charles Archive collection.

This blog explores the methods and techniques Freddie Charles used within his architectural practice when conserving, renovating and restoring historic timber-framed buildings.

Freddie Charles’ most important legacy to architectural conservation was the requirement for any building conservator to understand the form of a timber building within its historical and archaeological context. This is clear from the various drawings and plans that have featured in previous blogs.

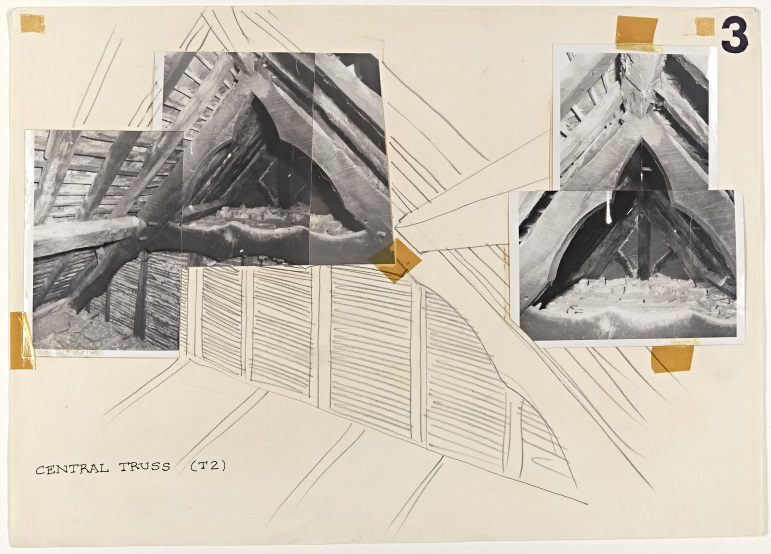

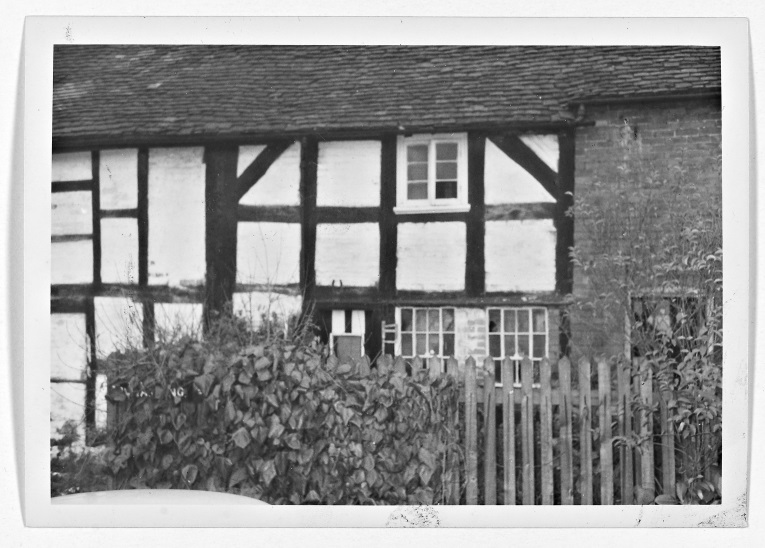

The common theme behind his techniques for historic building restoration is to take the building back to its main building phase, whatever period that happens to be. An example of this can be seen here at a building called Strand House that once stood in Bromsgrove, where Freddie noticed that although originally medieval, as seen in the photograph of the decorative elements of a central truss, more of the later 17th century alteration and construction survives, as seen in the photograph of the external view of the timber frame, so it made more historical and architectural sense to reconstruct this building exactly as it stood in the 17th century. Unfortunately it was demolished so this did not happen, but Freddie’s principles are clearly demonstrated.

Digitised photograph and sketch of possibly medieval central roof truss from The Strand House, Bromsgrove (CA_BA12857-5-17_03 :Demolished) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection

Digitised photograph of external timber frame of The Strand House (CA_BA12857-5-17_06: Demolished) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection

Charles saw well beyond the overall plan and form of a building, to the analysis of joint types, structural principles, the form of and nature of individual timbers to details such as historic carpenter’s tools usage. He drew heavily upon a detailed knowledge of these historic features to inform his conservation practice.

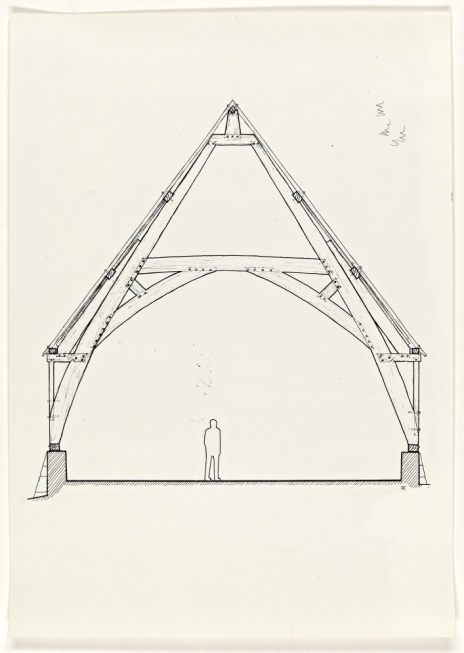

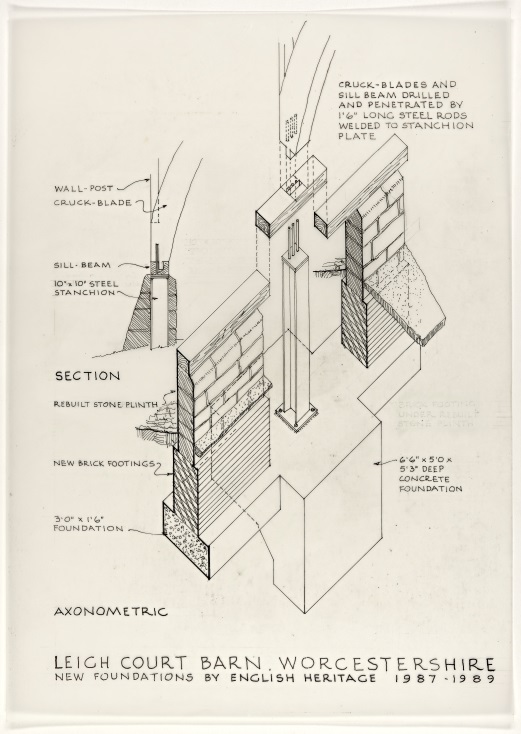

As someone who closely studied timber buildings he was aware of the timber resources originally used, noting within his book (Charles and Charles 1984) a surprising number of cases where medieval carpenters had squared a whole tree in creating an individual member of a building. This was the case not only for the massive cruck blades of Leigh Court tithe barn, but also many of the smallest parts, such as rafters, implying a large number of small, young oaks were cut from managed woodland within the region. Such information may seem irrelevant but may be deemed important for making like for like repairs, through finding a source of oak anything like the medieval equivalent may prove impossible in a modern context.

Leigh Court Barn (CA_BA12857-10-2_02) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection.

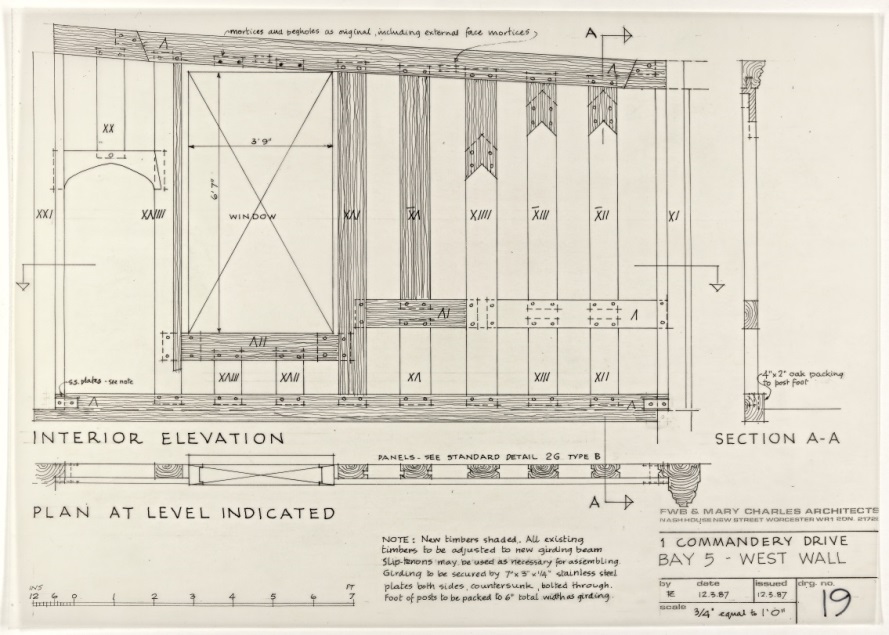

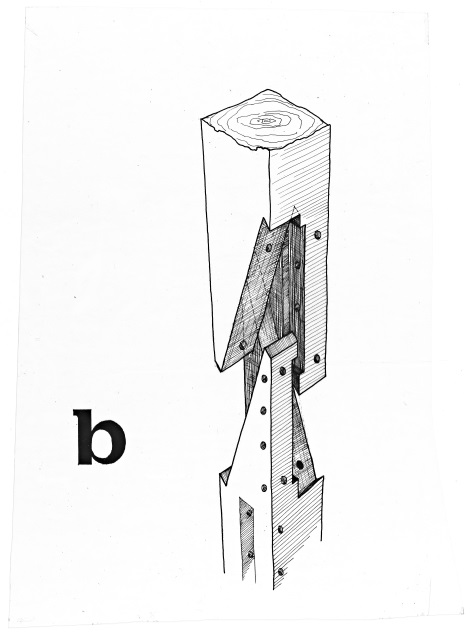

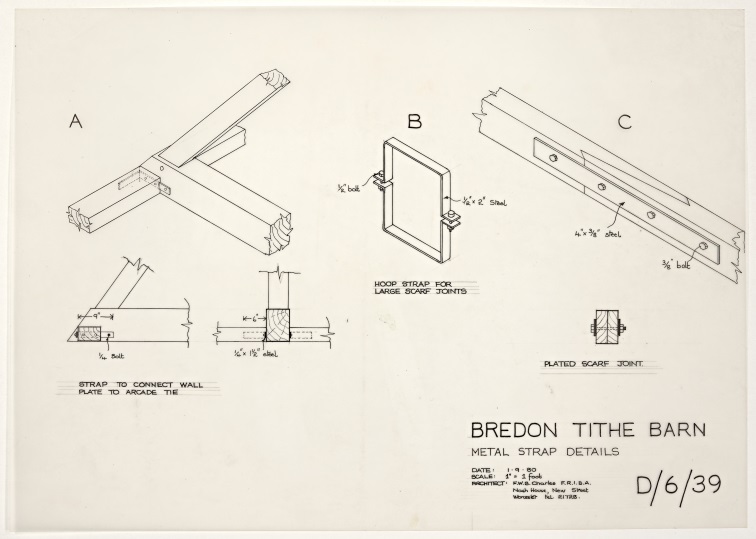

Charles predominantly used timber jointing in his repairs to match the physical characteristics of the timber, which is crucial in ensuring a continuing joint performance. This can be seen from the close matching of the fissures from a joint at the Commandery and Middle Littleton Barn.

Splicing together of old and new timbers within the timber frame at the Commandery (CA_BA13218-1-3_11) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection.

The method of splice jointing old and new timbers together, a technique used at Middle Littleton Tithe Barn (CA_BA12857-43_08, CA_BA12857-43_12) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection.

Another specification in his projects was that green, unseasoned oak was used throughout, as would have been used originally. He also employed the use of bolted iron work, which is a crude 18th or 19th century repair method, which added further support to timber joints.

Digitised photograph showing bolted iron work repair at Bredon Barn (CA_BA12857-4-7_24) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection.

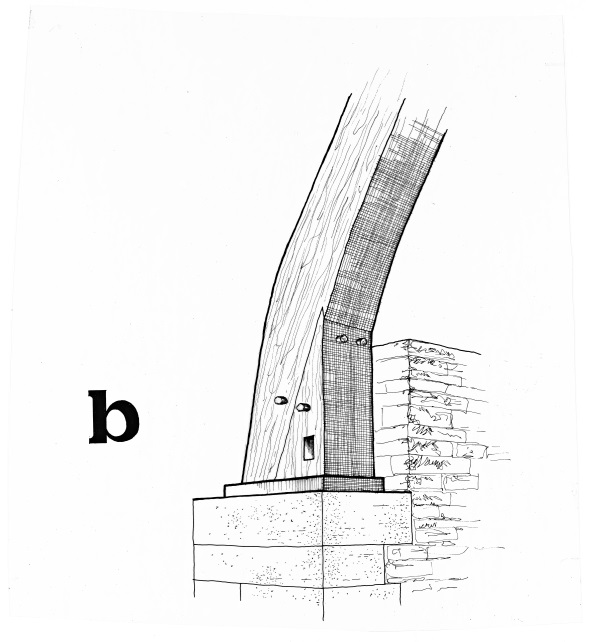

At Leigh Court Barn, he used steel stations, pins and concrete to repair a crumbling brick and stone plinth and then attached this to the bottom of the cruck. The below drawing shows how Freddie made sure these internal modern structural elements were hidden behind original or new traditional materials, so as to maintain the original character of the building.

Digitised photograph of internal repairs at Leigh Court Barn (CA_BA12857-10-2_04) © Worcestershire County Council: Charles Archive Collection.

Although techniques have moved on Freddie was a pioneer in his field who paved the way for modern conservation architects to develop the foundations he laid in repairing and bringing historic buildings into the modern world.

References:

Charles, F. and Charles, M. (2003). Conservation of Timber Buildings. London: Donhead.

Post a Comment