Find of the Month – January 2019

- 5th February 2019

It’s fairly common to find animal bones on archaeological sites. Most often there’s a range of different bones from an assortment of animals, left over from cooking or butchery. So when the finds trays start filling up with just one or two different bones, it’s a cue that something particular was going on.

Animal bone assemblage from a tanning pit – thanks to our volunteers for washing and processing many of our finds.

This was the sight that greeted all who walked into our finds processing room last week: trays filled almost exclusively with sheep metapodials (long foot bones, just above the toes and hoof). Why were so many found together? And where?

The assemblage is tanning (leather production) waste and was found in a pit cut into the backfilled Civil War ditch around Worcester. Tanneries are most readily identified by large collections of foot bones and horn cores, as these inedible parts were often left attached by the butchers who sold on raw hides. As soon as the skins arrived on site, these additions would have been cut off.

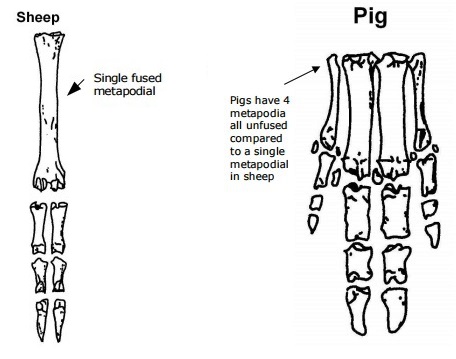

Bones within sheep feet look distinctive from those of other animals (taken from Animal Bone Identification resource created fro the Jigsaw Project).

Traditional methods for producing leather are lengthy, messy, smelly and require easy access to water (you can read more about the process here). As a result, tanneries were usually located on the edge of towns alongside a stream – not good news if you lived downstream. Despite the unpleasant nature of tanneries, in the absence of plastics and synthetic fabrics, leather was a vital material for making shoes, bottles, bellows, harnesses, saddles and a host of other items.

A selection of the sheep metacarpals (front foot bones) and metatarsals (back foot bones) found. Some of the bones come from young animals where the end of the joints hadn’t yet fused.

Due to the importance of leather, many specialist jobs and distinctions between types of leather working were made during the medieval period and following few centuries. Whilst tanners had the right to purchase cow hides, those who did not – and worked with sheep, goat, deer and pig skins – were known as tawers. Despite the odd cattle bone and fragment of pig jaw, most of the bones are from sheep; suggesting it was a tawer, not a tanner who operated on this site.

Organic materials don’t survive well in the ground (although they can do if charred or in extremely dry, cold or waterlogged conditions), so the archaeological record is only a partial picture of the past. Look carefully for clues though and the gaps start to fill in.

Post a Comment