Find of the Month – February 2019

- 16th March 2019

Over 3000 years ago, fingertips were pressed into the damp clay of a large pot, creating a patterned band and dimpling the top. Once dry, it was fired and used before being broken – several large fragments were put into an isolated pit on the gravel ridge east of the River Severn.

Prehistoric pots, especially large decorated pieces, don’t turn up very often: it was produced in modest quantities and is often fragile due to relatively low firing temperatures. But during February, fragments of an incredibly large early or middle Bronze Age pot were found. Thanks to our observant and skilful archaeologists, these crumbly sherds of hand decorated pottery were carefully excavated, lifted and brought back to the office for cleaning and analysis.

Left: Large sherd of a decorated early-middle Bronze Age pot – the colour change from black to brown is due to differing oxygen levels during firing. Right: Careful cleaning of the fragile pot with a damp sponge.

Fingertip decorations, along with patterns created by twisted cords, are typical of pottery made at this time. Pots may have been marked purely for aesthetic reasons, but it’s also possible that the act of creating patterns and leaving lasting finger impressions on pottery held meaning.

From the recovered fragments, we can see that this pot was thick walled and very wide. Bronze Age pottery is often found in burials, as cremation urns or accompanying grave goods, but this vessel appears too large to be a burial urn. So what was it for? One key suggestion is feasting – large gatherings where food was served to a large group. It’s been argued that only some early prehistoric pottery was made for everyday use and that until the late Bronze Age many ceramic vessels were reserved for special purposes; namely, burial and social gatherings.

Prehistoric organic materials rarely survive, so it’s easy to forget that we’re missing all the baskets, wooden items, worked leather and textiles that were undoubtedly used alongside pottery. Without these objects, it’s harder to work out how the large, heavy ceramic vessels fit into the lives of the communities who made and used them. Intriguingly, several sherds appear to contain a residual layer of whatever the pot last held. A scientific technique, inventively know as organic residue analysis, may be able to give an idea of what was inside the pot, but that doesn’t necessary answer the question of why – was the pot used for storage, feasting or an entirely different purpose?

Pot sherd with black residue on the inside surface

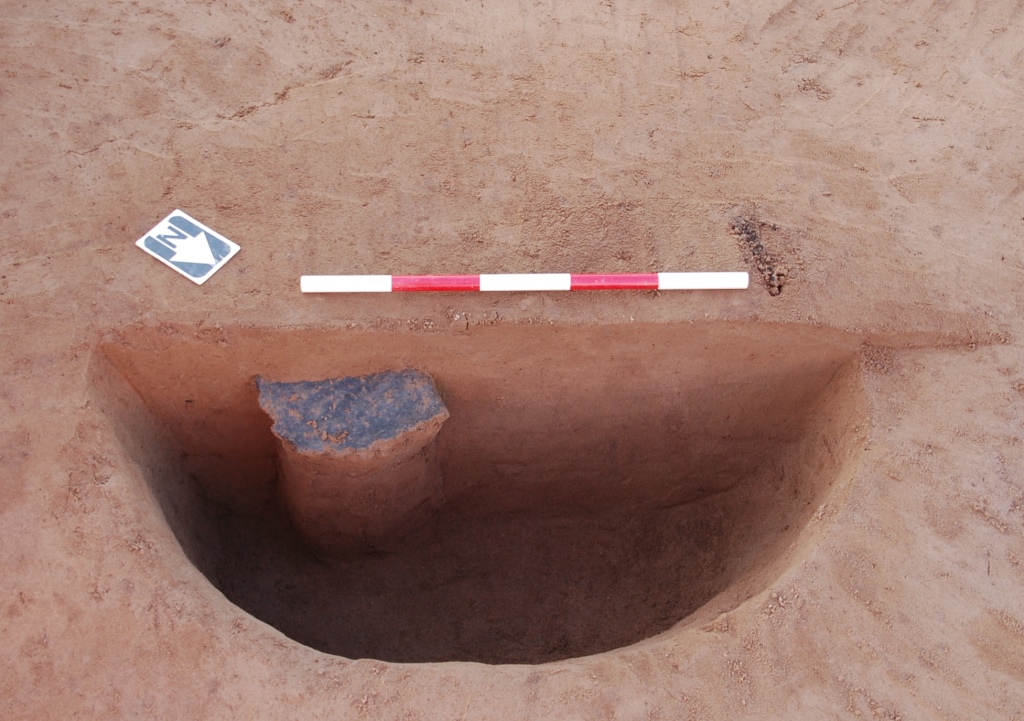

Let us return to the ridge of ground by the River Severn where this pot was found. The only known Bronze Age activity in the immediate vicinity is the pit, which contained little besides the pot sherds. This wasn’t a rubbish pit within a settlement were a broken pot could be easily thrown away – something more ephemeral was going on. Given the material the pit was filled with, it appears to have been deliberately backfilled rather than being left open to gradually silt up. It’s probable that the pot sherds were intentionally included and feasible that they weren’t just buried as waste.

Half excavated pit containing decorated pottery (50cm scale)

To go back to the idea that some pots were special, rather than everyday items, it’s intriguing to see that throughout the Bronze Age pots gradually go from being highly decorated to more lightly decorated and then predominately plain. Despite the perception of technological development as an ever upwards trajectory, the use and development of technologies changes with the values of society, as there’s no need or incentive to invest in a technology that has little value to you.

With the introduction of copper and bronze to Britain, the ways in which other materials were used changed – not just pottery, but stone, flint, wood, textiles and so on. Alongside straightforward replacement of one material for another, new technologies often bring skills and techniques that can be applied elsewhere. For instance, metal working involves creating and controlling high temperatures, which is relevant to firing pots. Change can also be a shift of purpose rather than a rendering obsolete; it’s feasible that the increased availability of metalwork caused the perception of pottery to alter, so that it became seen as a more mundane and practical material.

When damp clay was shaped into a large vessel and fingertips pushed into its surface over 3000 years ago, it was done for a reason. We can puzzle over why, but above all seeing someone’s fingerprints is an incredibly personal connection that collapses the intervening millennia and allows us to touch the past – that is what makes archaeology so special.

Touch the past – fingertip impressions on a raised band around the Bronze Age pot

Post a Comment