Juliana la Pottare

- 8th March 2019

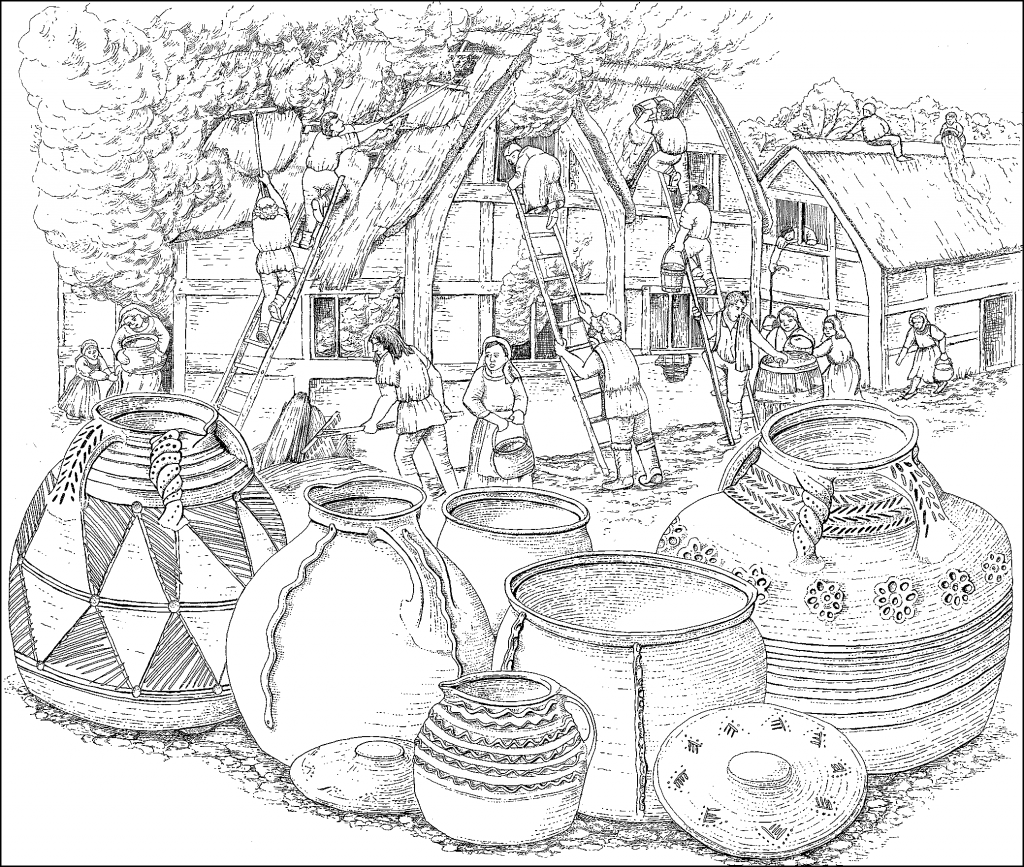

Dig a hole in any medieval town or village in England, and you’ll find pottery. On most medieval excavations, potsherds are likely to be the most abundant type of artefact. Popular ideas about medieval crafts such as pot-making are dominated by images of bearded men in dirty aprons, such as this extract from this article about medieval clothing:

“A coif, a linen or hemp bonnet that fit close to the head and was tied under the chin, was usually worn by men undertaking messy work such as pottery…”

But there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that women could play a significant role in the workshops and kilns of medieval Europe. Matching the archaeological and historical evidence offers a glimpse into the life of Juliana, a potter in late 13th-century Worcestershire.

We know a lot about the use, distribution, and styles of medieval pottery in Worcestershire. But we know very little about the people who made it. Potting was a relatively low-status occupation in medieval England; there were no potters’ guilds, and documentary references to the craft are rare. It is a curious paradox: we can see the potter’s fingerprints and follow the smudge of their thumbs as they put the finishing touches to a vessel, but we know so little about who they were and how they worked.

From the late-11th to the 14th century, pots were often made in small workshops in rural areas. In Worcestershire these seem to be sited near woodland, for ease of access to fuel for the kilns. They were also close to sources of Mercian Mudstone or Lias clay, and had good links by road or river to the markets at Worcester. Some kiln sites have been discovered in the area of Hanley Castle, near Upton-Upon-Severn. ‘Malvernian’ pottery was produced here from the 13th to the early 17th century. But we know from documentary sources that Worcester-type wares were made in a number of places, including Northwick, Sidbury, Inkberrow, Bromsgrove, Kempsey, and White Ladies Aston. Their wares included crude handmade cooking pots, but also elaborately glazed decorated pitchers and jugs.

Pottery found in a house that burned down about AD 1250 in Deansway, Worcester

The Kempsey potters

References to the Kempsey potters are particularly interesting. In the summer of 1275, four royal justices came to Worcester. Over six weeks, they heard hundreds of cases, many of which are recorded in the Worcester Eyre. Among the defendants was Henricus le Potter de Kemeseye, arrested — alongside 21 others — on suspicion of larceny, an offence roughly equivalent to theft. Fortunately for Henry the Potter, all were acquitted by the jury.

The next reference to a potter at Kempsey is from a lay subsidy assessment: a record of taxation probably drawn up sometime in the years 1276-82. It records the names of the heads of each household that possessed goods valued over six shillings and eightpence, and the amount of tax paid by each. Listed among the Kempsey taxpayers is Juliana la Pottare. Surnames at this point were generally derived from the trade or origin of each person, or sometimes a distinguishing feature or family relationship. It is often assumed that women with names reflecting trades are just the wives of tradesmen, a view informed by the expectations of many historians in the 19th and 20th centuries. In most documentary records, it is difficult to demonstrate otherwise. But the tax assessment records the head of the household. If Juliana is named, it was she who led the household, made the pots, and paid the tax. She paid 20 pence. For comparison, the same sum was paid by the village Coupare (Cooper = barrel-maker).

J W Willis-Bund and John Amphlett, who published the tax assessment in 1893, were struck by how commonplace it was for women to be listed as heads of the household:

“On looking over the list of names it is striking to see the large number of females, either widows or women, holding in their own right… the list might be extended to almost any length” (1893, vii).

No other potters are listed from Kempsey. It may be that others were less prosperous and were therefore exempted from the tax – no Hanley potters are listed, possibly for this reason. But given what we know of the small scale of this industry, it is most likely that Juliana ran the only pottery kiln in the village.

The next reference to Kempsey potters comes from the Red Book, a fascinating transcript of 12th and 13th century records of the Bishop of Worcester, published by Margory Hollings in 1934. The translation below was provided by archivist Bethany Hamblen:

Extract from Red Book, 1299 extent of Kempsey, p. 71

Henry the Potter holds six acres of land for service of 2 shillings 6 pence annually at the aforesaid four terms. And he owes in all respects just as the aforesaid Alicia. And moreover if the Lord shall have wished it he will care for his pigs. And he shall have nine dry measures of rye and barley and one piglet called Merlyngere bok*. And if he is at daywork, he will give 6 pence for the aforesaid 3 terms just as the aforesaid Alicia le Rom.

Potting was generally a seasonal occupation, and Henry evidently supplemented his income with farming 6 acres, and looking after the Bishop’s pigs, in return for rye, barley and a piglet. There’s no mention of Juliana by this date. Henry is the only potter listed, and the 1299 account is very detailed, which supports our theory that there was only one pottery workshop in the village.

So, what’s going on? If the Henry in court in 1275 is the Henry listed in 1299, why is Juliana the head of the household in 1276-82? One possibility is that there are two Henrys — perhaps father and son — and that Juliana took over the workshop after the death of a spouse or family member, subsequently leaving it to the younger Henry by 1299. It is also possible that the two Henrys are the same person, but at the time of his brush with the law in 1275 he was not the head of the household: perhaps a young man learning his trade from Juliana.

Evidence for Women as medieval potters

There are few records of how pottery workshops operated in medieval England, but archaeological evidence and parallels from the continent are useful. Production was organised around family-run workshops. The involvement of the whole family in the process is indicated by the frequent occurrence of children’s fingerprints on medieval tiles and waste products from kiln sites. The stoneware potters of Siegburg, whose wares turn up frequently in medieval England, operated a guild-system in which workshops were run by masters, with assistance from workers and apprentices. If a master died or was incapacitated, his wife was permitted to run the workshop. (see Maureen Mellor’s paper, ref. below). The custom of a widow taking over her husband’s trade is likewise well-documented in England.

Mid-15th century potter on a playing card from Bohemia. Source: Gaimster 1997

One of the most famous and striking images of a medieval craftswoman is from a mid-15th century playing card. Part of a set depicting Habsburg court staff, the card is number 2 in the suite bearing the arms of Bohemia. It shows a woman working at a potter’s wheel, using a bone tool to form the ribbed body of a stoneware jug.

We don’t know exactly where Juliana’s kiln and workshop were situated. No archaeological evidence of a kiln has been unearthed in Kempsey. The remains may be within the modern village: we’d love to hear about any medieval pottery found in people’s gardens. Without the kiln, we can’t yet distinguish the Kempsey wares from the other local workshops. Nonetheless, we’ve almost certainly found lots of Juliana’s pots in the thousands of sherds of Worcester-type medieval pottery that turn up in excavations across the county. We know so little of the lives of Juliana and Henry, but the fruits of their labours survive. Even after 700 years, the green glaze of their pots shines out from the soil, as glossy as ever it was.

The many women listed alongside Juliana in the tax rolls of the late 13th century demonstrate that women were by no means invisible. But in medieval English society, women were subject to structural sexual inequality that permeated every level of practical, moral, religious and intellectual life. Nonetheless, they persisted.

*If anyone can help us with why on earth the piglet appears to be called Merlyn, and the meaning of ‘bok’, we’d love to hear from you – it has us stumped!

Rob Hedge

Further reading

Bryant, V 2004 Death and desire: Factors affecting the consumption of pottery in medieval Worcestershire, Medieval Ceramics 28, 117-23

Gaimster, D 1997 German Stoneware 1200-1900. British Museum Press

Hollings, M 1934 The Red Book of Worcester, Worcestershire Historical Society. Available on Level 2 at The Hive.

Hurst, JD 1990 Documentary evidence for medieval potters in Worcestershire, Transactions of the Worcestershire Archaeological Society Ser. 3, 12, 247-250

Mellor, M 2014 Seeing the medieval child, in D M Hadley and K A Hemer, Medieval Childhood: Archaeological Approaches, 75-95

Willis-Bund, J W, and Amphlett, J 1893 Lay subsidy roll for the county of Worcester, circ. 1280. Worcestershire Historical Society. Available online

A good intro for those who are interested in medieval life and who maybe have a niche interest.