Archaeology 50: Adrian Tindall

- 24th October 2019

Our 4th County Archaeologist was Adrian Tindall, who shares these memories.

The River Severn was frozen over when I first arrived in Worcester in Christmas 1986. Shivering by an electric fire in Henwick Park lodge, with the water pipes frozen, in an unfamiliar city, I briefly doubted my decision to leave my young family temporarily in Manchester to take up the job.

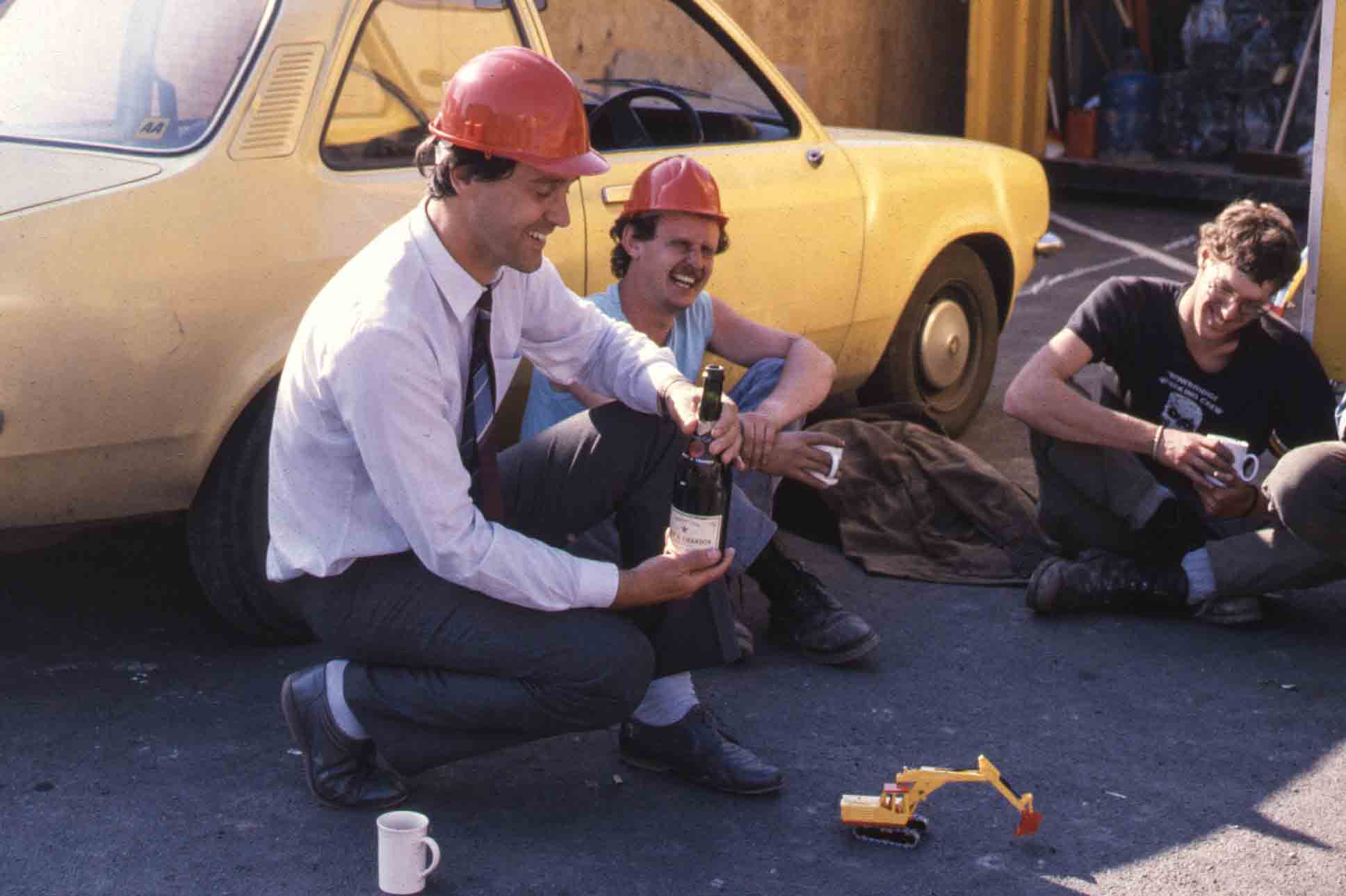

Adrian Tindall, Malcolm Cooper & Robin Jackson

The county archaeology service had been through a period of painful upheaval, its relationship with the county council (then Hereford and Worcester, an unhappy marriage between two proudly-independent counties) remained fractious, and its future insecure.

The most urgent priority was a period of stability and the rebuilding of working relationship with the county council. The service had two huge advantages, however: a rich multiperiod archaeological resource spanning two historic counties, and a team of knowledgeable and committed professionals capable of managing, investigating and interpreting it.

I vividly recall my first sight of the service’s temporary accommodation, sharing a primary school in Warndon. It was roomy and serviceable enough though hardly fit for purpose, with its minimal supply of electrical sockets and Lilliputian cloakrooms. I remember receiving a warm welcome from the staff, who must have been as apprehensive as I was. It was always a very sociable workplace.

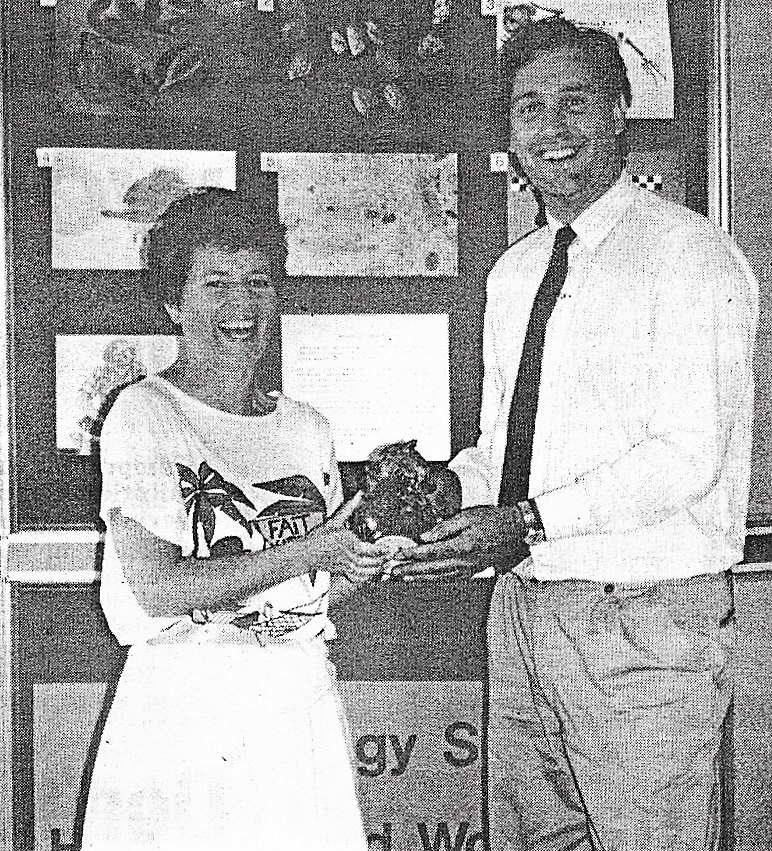

The first thing that struck me was the wealth of the county’s archaeology. On my first day in January 1987 I paid a site visit with Simon Woodiwiss to Vines Lane, Droitwich, where Derek Hurst (then Droitwich Archaeologist) was directing the excavation of a small Roman inhumation cemetery.

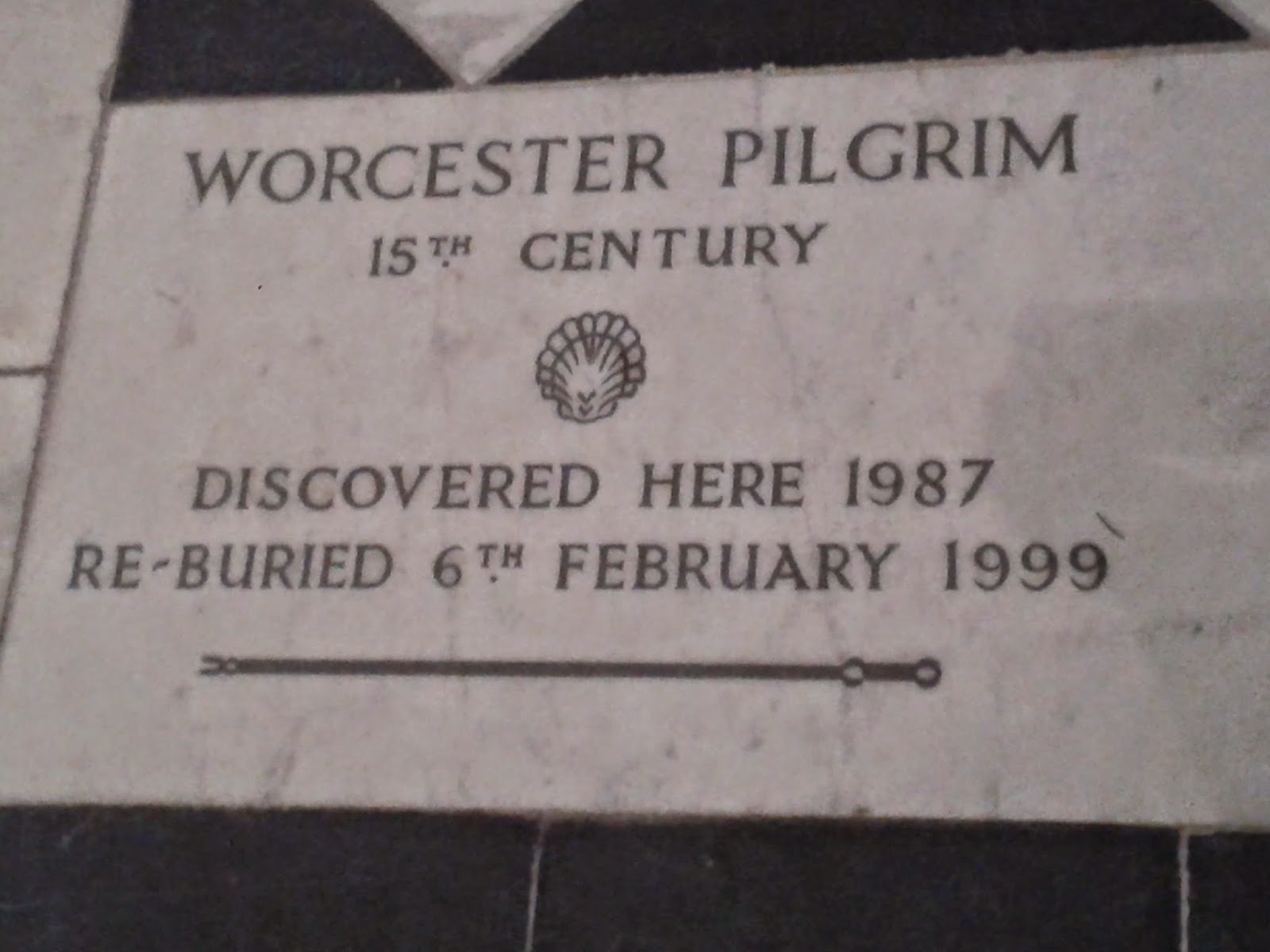

In the following months, two further significant burials came to light. In Worcester, excavations at the base of the cathedral south tower revealed the burial of a 15th century pilgrim, complete with woollen clothing, knee-length leather boots, wooden staff and cockle shell. The survival of his clothing and accoutrements made the Worcester Pilgrim a unique find. A few months later, gravel-quarrying at Aymestrey near Leominster uncovered the Early Bronze Age flexed inhumation of a young child, accompanied by a bell beaker and flint knife, contained in a stone cist. Another remarkable survival.

Behind the scenes, service staff were busily working on several major EH-funded post-excavation projects. These included reports on excavations of multiperiod salt production sites from the brine springs of Droitwich, and the extensive late prehistoric lowland settlement at Beckford, near Bredon Hill.

The late 1980s was a transformative period in British archaeology. County Sites and Monuments Records (now HERs) began to migrate from card-based to computer-based systems: a process as revolutionary as the later advent of GIS. Job creation schemes, a lifeline for the profession since the 1970s, were coming to an end, to be superseded by the first developer-funded archaeology, introduced by stealth, negotiation and bluff until its formal recognition in the planning process with the publication of PPG16 in 1990.

The most significant and ambitious of these developer-funded excavations was the Worcester Deansway Dig. It was managed by a talented team led by Charles Mundy, Malcolm Cooper and Hal Dalwood, and saw the arrival in Worcester of such stalwarts as Victoria Bryant, Robin Jackson and Laura Templeton. Sadly, of course, Charles and Hal are no longer with us – a huge loss both to Worcestershire archaeology and to the wider profession.

Deansway dig

The Deansway excavation was the largest ever undertaken in the city, covering nearly 2000m2 and revealing deeply-stratified deposits showing the urban development of Worcester from Romano-British small town to late medieval city. It was also notable as one of the first public-facing development-led excavations in the country, with a visitor centre, viewing platforms, an army of local volunteers and a year-round programme of public events and school visits. It was far ahead of its time, and set the benchmark for developer-funded urban excavations thereafter in the UK.

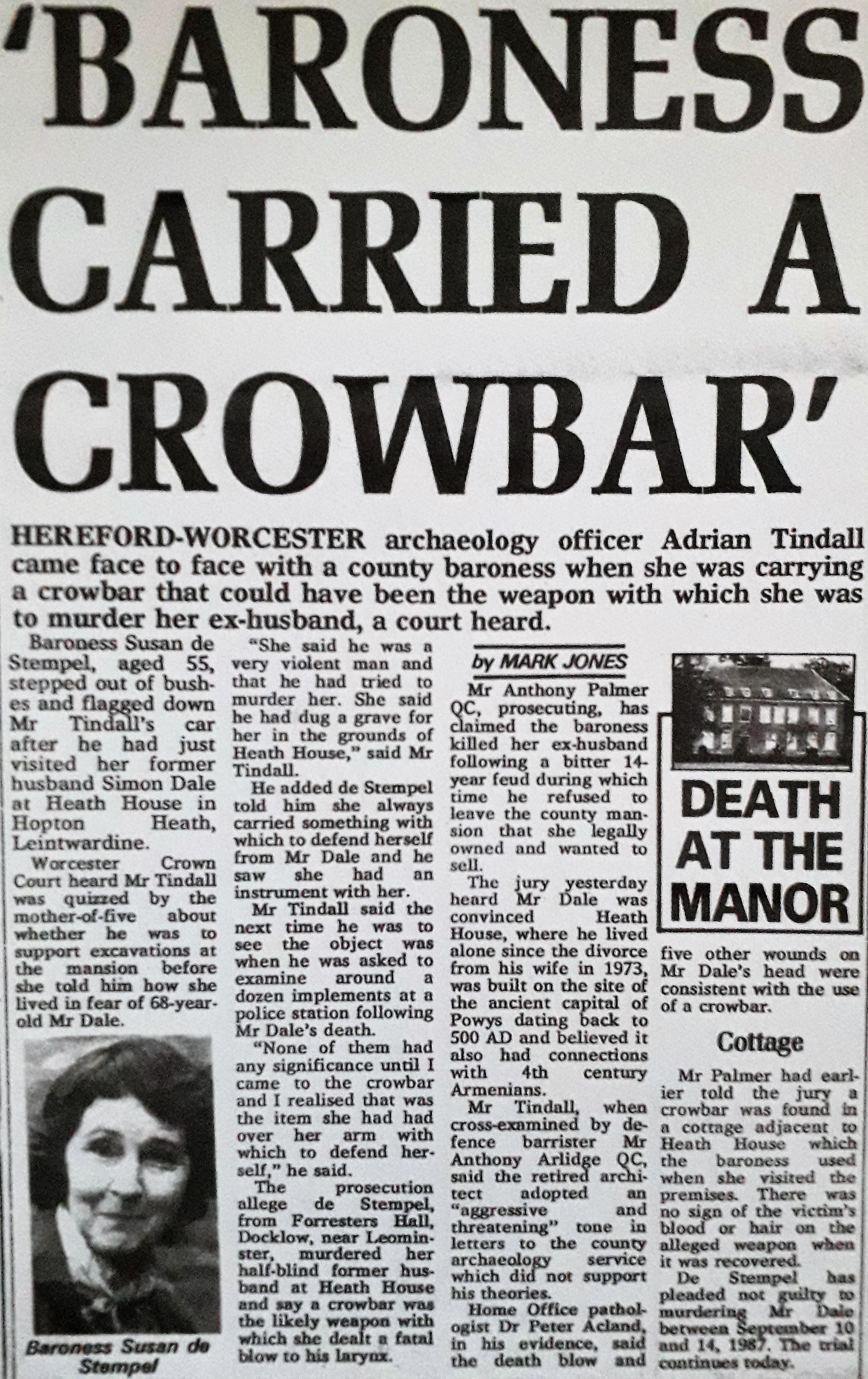

My time at Worcester was always eventful, sometimes too much so. Following the retirement of the County Museums Officer, I was asked to act in this role and undertake a review of the county museums service. During this time the County Museum at Hartlebury Castle was burgled, and I found myself standing in driving snow at 2am, surrounded by police officers and dogs, surveying a shattered and bloodied rooflight. My time in Worcester was also book-ended by the cause célèbre of Simon Dale, an eccentric recluse whose outlandish theories about the origin of his Herefordshire mansion had been the bane of my predecessor and every archaeologist in the region. My own involvement began with a site visit and a bizarre encounter in the grounds with his former wife, the Baroness Susan de Stempel, and ended some two years later in the witness box at Worcester Crown Court, where she was on trial for his murder.

Ah yes ! This is where I came in s a volunteer, working on the pottery from the Deansway with Charles Mundy. So sorry to hear he is no longer with us. Thank you for these posts allowing me to catch up with my time at the Hereford and Worcester Archaeology all those years ago.