Lockdown day in the life … Finds Supervisor

- 17th April 2020

Today we look at a lockdown day in the life of our Finds Supervisor, Rob Hedge on 16th April 2020

Today, I’m looking at some intriguing pottery from an excavation by Wessex Archaeology North. I’ve been asked to write an assessment. This is a basic quantification of different types of pottery: what type of vessels are present, where they’ve come from, and what date they are. The assessment highlights anything special or unusual about the finds, and allows a specialist to recommend any further work required to understand them. For pottery, this could be residue analysis, scientific dating, or petrographic work (taking a very thin slice to analyse minerals in the clay). Or we may just require more time to look at the material in more detail, and carry out statistical analyses.

The time it takes to do the assessments varies – highly fragmentary or unusual material can take a long time. But for this site I’m aiming to record about about 25 an hour. I’m part time, so in normal times that would be about 150 each day, minus time for admin and other parts of my job. But these are far from normal times.

Our finds workroom in The Hive is closed, so I’ve set up a workspace in our spare bedroom/office/playroom. I’m by the window, with plenty of natural light and a view of the garden.

But before I can get started today, our youngest child needs to go to the doctor, so I’m on homeschool duty for the oldest. We collect some water samples on our morning exercise, from the River Severn, the Barbourne Brook, and our garden pond.

|

We put the WAAS digital microscope to work in a makeshift lab on the dining table, with a Calpol syringe for a pipette, and take a look at our samples under 200x magnification. |

| Scarily, this sample from the River Severn contains human-made artefacts alongside the sand and microscopic creatures: microfibres. Unmistakable markers of Anthropocene deposits. |  |

After lunch, I start work. The pottery from this excavation mostly dates to the 1st century AD, but which part? There’s some earlier material that dates back to the Middle and later Iron Age. And some that post-dates the arrival of Roman troops in AD43. Is this a long-lived settlement, well established by AD 43 and continuing uninterrupted through the turmoil of those times? Or are there several distinct phases? To unpick this, I have to check the pottery against the site records, look at the plans showing the spatial layout, and pay close attention to the condition of the material. This is why it’s so important for specialists to talk closely to the excavators.

A ditch containing pottery from the 3rd century BC does not necessarily mean that the ditch is the same date. Those of you lucky enough to have gardens may well have been digging them over the lockdown. My veg plot, in a Victorian suburb of Worcester, contains a lot of pottery from the last 150 years, and some even earlier, from when the area was farmland. But my carrots are not 150 years old. We call this kind of background material ‘residual’. Added to this is the conundrum that the infilling of an archaeological feature like a ditch often takes place after the feature goes out of use. So, let’s look at a piece of pot.

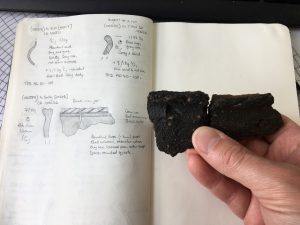

|

In total, there were 7 pieces of this vessel in a gully, probably chucked in as the gully was gradually silting up. These two rimsherds can be fitted back together, suggesting they were probably dumped in the ditch soon after the pot was broken. Conjoining pieces are rare if the artefacts are residual. You can see voids on the dark outer surface – these are where chunks of fossil shell have dissolved in contact with the soil. On a fresh break, you can see the white speckles.

Fossil shell-tempered wares occur through the Iron Age and Roman periods in the Midlands. But one thing that helps us to narrow the date down is the type of vessel. It’s a bead-rim jar, with a slight groove in the top of the rim (probably to allow a lid), and diagonal slashed decoration around the outside of the rim. Very similar shell-tempered bead-rim jars found further southeast are thought to date from roughly AD25-50. But at what date did they arrive in the Midlands? That’s the question I’m wrestling with today. Usually I’d have The Hive’s quarter of a million books and reference resources at my disposal, but only a fraction of the sorts of old site reports and monographs we use for comparison are available online. So it’s a little trickier than usual, but we’re doing our best.

We hope this site will help us untangle how trade, consumption, and daily life were affected in a period of change and upheaval around the Roman conquest. The irony of doing this work during our own time of upheaval is not lost on me. I manage about 3 hours — and around 70 sherds — before the demands of life in lockdown with a newborn and a 5-year-old take over.

Thanks for that, Rob.

Good luck with the homeschool duties!

Fascinating. Can we please have further posts on what the various staff do, both at home and in normal times when in the hidden bits of The Hive

Hi. Yes, we’ll be sharing some of the other staff are doing whilst at home shortly.