Animals & Ancestors: Bones from the Pyre

- 17th July 2020

What do animals mean to you? For our second blog in the series about prehistoric landscapes, Liz Pearson, our Environmental Archaeologist, explores the tale of two Bronze Age burials, their unusual choice of animal companions and relationship with the land.

From the edge of the woodland we see four people lay the body of a young person upon a tall stack of oakwood. From a distance, for we can’t see for sure, he looks like a teenage boy. He’s well built with strong shoulders, lain on his left side, one hand draped over his chest. Around him are the bodies of a roe deer and pig, along with a large joint of meat. A crowd of onlookers stand around as one person leans forwards and sets light to a layer of birchwood, which flares up quickly, burning hot underneath the weight of the oakwood above.

A few years later, we see a similar scene. Only, this time four people lift up the body of a woman and place her on a cremation pyre. With her, they place the body of a dog.

Photo by Lesly Juarez on Unsplash

The oakwood burns steadily for some time, then cools. After they watch the pyre burn out, the people who placed the body of the boy, or young man, on the pyre came back to collect the remains. The bones have burnt white: a consequence of the pyre’s heat. They rake and winnow the bone from the pyre residue. Collecting most of the bone, they scrape it into a pit, freshly dug nearby. We don’t see what happens to the remains of the woman and the dog.

From Pyre to Cremated Bone

It’s July 2014, and we’re standing in the middle of a Bronze Age round barrow (a burial monument) on land about to become part a quarry near Meriden, Solihull, formerly owned by Tarmac. There are two complete barrows and part of a third which we think were used sometime between 3,600 and 3,400 years ago, during the middle Bronze Age. We’ve been here before on Explore the Past, collecting samples of charcoal from the mound at the centre of the northernmost barrow, contemplating the possible Thinning of the Wildwood.

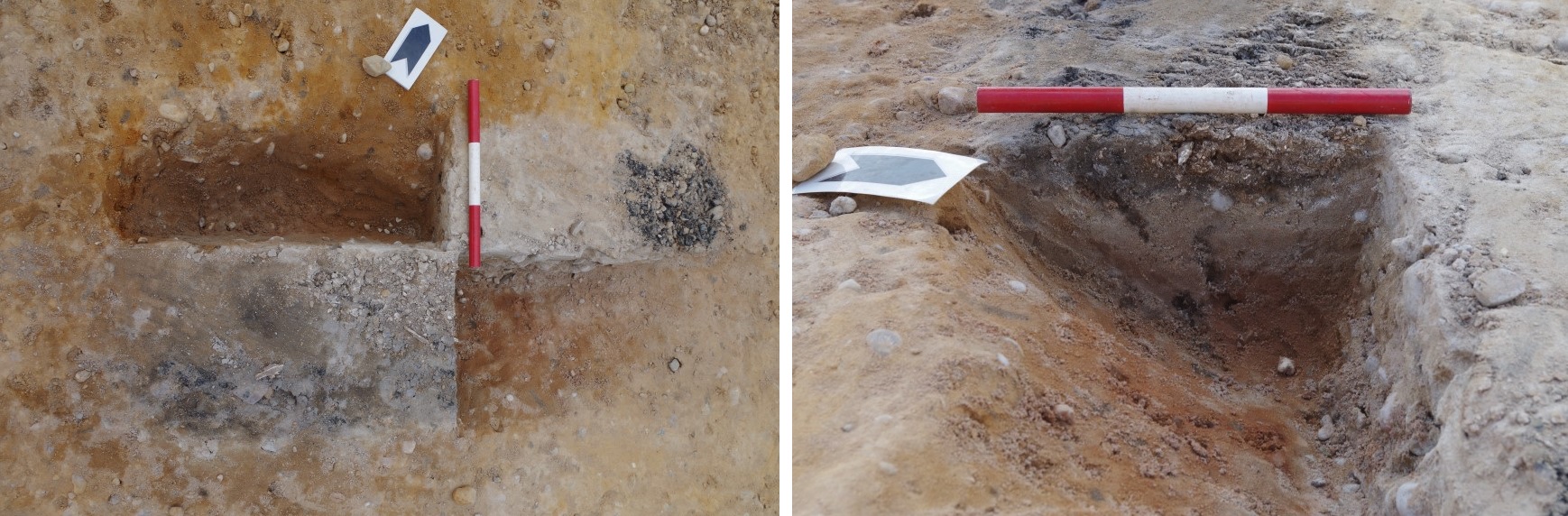

We carefully dig a burial pit in the northernmost barrow (shown below) in quadrants and spits, keeping material from each block of soil separate. Back at the offices, we process the samples by a flotation method, picking out all bone from both the light floated material and heavier residues. Like the charcoal, this burnt bone has a story to tell.

Recording the cremation deposit of a teenage boy found in the centre of a Bronze Age round barrow (burial monument) at Meriden Quarry, Solihull

Pit containing cremation deposit excavated in quadrants (30cm scales)

The Devil in the Detail

Once with the human bone specialist, several characteristics that are peculiar to this cremation jump out at her. Skull fragments are common, and most of them are from the right side. She notes unfused ends of long bones and there are many small bones of the hands and feet, along with bones from all elements of the body. The shoulder blade, at the point where it anchors into the muscles at the back of the shoulders, is fairly robust for a young person. Curiously too, there are some wormian bones, formed from extra bone growth at the sutures, or joins, of the skull.

Animal remains are quite common in Bronze Age cremations, but they’re particularly frequent amongst the remains of this boy or young man.

Researchers think that finding skull bones mainly from one side of the head reflects a body lain on its side. One side, facing upwards, remains more accessible for collection after the pyre has burnt out and collapsed. Unfused ends of long bones suggest a young person, but not a child; and those wormian bones, possibly trauma just after birth. We find bones for all parts of the body, which the guardians of the cremated remains must have carefully collected. We know some details about his life, but not how and why he died, or if any trauma just after his birth affected his long term health.

The bones of the woman look worn and chalky, and little survives of her body. They may be a memento mori burial, the remainder of the cremation being buried elsewhere, and a token amount left behind. And, what of the dog? Was that her dog? Perhaps she was a young female hunter, or a shepherdess?

Animals, Wildwood and Farm

The roe deer, the pig and a beef joint burn with the boy: three animals to transport and accompany him into another life. Animals from wilderness and farm, representing a life lived with animals. And, most likely, a life where the cycle of life and death is in plain sight much more than it is today.

Were the animals of special meaning to the boy? Or, were they part of a burial rite, in the same way that we throw flowers into a grave today? Researchers think these are symbols of the close connection of people with animals, rather than necessarily being the actual animals that a person shared their life with. They are too, symbols of the landscape around them: in this case, of wildwood and farm.

In burials of the earliest farmers in the British Isles, of Neolithic to early Bronze Age date, we’re more likely to find parts of wild animals – skins, teeth, claw and horns: seemingly, the remains of mortuary costumes. Yet, by the middle Bronze Age, we find both wild animals (mostly deer) and whole domesticated animals like sheep, cattle, pigs and dogs. Life has changed. The forest is becoming more distinct from the farmland outside the door. The forest or wildwood is ‘otherness’, but still closer than today; still covering vast expanses of land.

By Ungeurran Urban on Unsplash

Retreating Woodland

We’re looking at a changing landscape even more so today. The forest is retreating further away – not just physically, but in our own minds. We are today, somewhat disconnected with woodland and to a degree with animals. Most of our experience of animals is with those that are our pets, as few people work with animals or farm them for food.

Animal remains found in prehistoric burials show us how much the lives of people were intertwined with animals; how they represented cycles of life, and how the local community were dependent on them for their livelihood. It’s likely that they cared for, and even revered them, despite culling many for their food. A life lived with animals – you could say that it’s written into our DNA.

People living in this Bronze Age landscape depended on regeneration of woodland, soils, animals and plants – all together, because all are connected. They were conservationists in a past age, looking out on a woodland pasture landscape, the wildwood beyond. Both trees and pasture knitted together fragile loamy and sandy soils. As the woodland receded, farmland expanded, but animals (livestock) have remained important in a landscape with less than perfectly fertile soils.

Over a thousand years later, we find people, not from this area, walking small black cattle, sheep, pigs, chickens and gaggles of geese along droveways and across ridgeways past Meriden, to distant farms, and towards cattle markets in the east. There are signs that they walk ancient byways, with their roots in prehistoric times. Coming up soon: we explore ways in which we can investigate the wanderings of people, and animals.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Tarmac for funding this work, and to Jacqueline McKinley of Wessex Archaeology who reported on the cremated human bone from this site.

More tales from Meriden:

Fascinating stories are found in the smallest of archaeological clues: charcoal and pollen. Recent analysis illuminates the prehistoric landscape at Meriden and choices made by our ancestors 3,500 years ago. To kick off this blog series, we begin by setting the scenery – literally!

Tales from a Prehistoric Landscape

Looking for an overview of the archaeology at Meriden Quarry? This online talk, given for the Festival of Archaeology 2020, runs through the whole human story written across this incredible landscape – from Mesolithic campers to a trend setting Neolithic community, the sorrow and love of Bronze Age mourners, then the arrival of Iron Age landscapers.

Post a Comment