Find of the Month – Historic Wall Paintings

- 20th August 2020

This month we have something a bit different to share with you. Whilst our Find of the Month blogs tend to feature interesting archaeological finds discovered by our field team, we also have staff specialised in recording historic buildings. These projects usually take place when a building of historic interest is refurbished, developed or demolished. A little while ago, we carried out another phase of recording at a building in Monmouth with some rather nice wall paintings dated to about 1600. We can now share the story with you.

Our historic buildings specialist, Tim Cornah, explains:

View of the Kings Head frontage from Agincourt Square

The Kings Head in Monmouth may not look medieval from the outside, but appearances can be deceptive. The building has played an important and well documented role within Monmouth’s history – Charles I supposedly stayed here during the Civil War in the 1640s. A bust of Charles, added to the ground floor in the 1670s, certainly makes clear the Royalist leanings of the owners. Long held local rumour also suggests that the Kings Head was built over filled in civil war defences; our findings challenged this.

Bust of Charles (probably Charles I) added to the ground floor of the building, probably in the 1670s

One of the joys of historic building survey is accessing the forgotten space of buildings and revealing that which has long been hidden. This building did not disappoint. In a first floor room, behind studding for a modern ensuite bathroom and layers of wall paper and paint, was an original stone wall. Over this remnant of a circa 1600 building was the original layer of lime render with faded paintings just visible. Closer inspection revealed the possibility that these paintings spread across much of the wall behind later coverings.

Wall paintings as initially seen showing a possible column top and other decoration (scale shows distance in centimetres from the floor).

It initially seemed that these paintings formed part of a frieze at the top of the wall, with a possible column top to the right of the scale. Whilst this in itself gave little information, most domestic wall paintings were located in principal rooms and the majority of these within first floor chambers, as is likely to be the case here. Across the Welsh Marches, the majority of wall paintings date from 1575-1625, as many medieval buildings were modified in the wake of the Reformation. Around 1625 there appears to have been a change in style, with examples prior to this date typically spreading across the whole wall and being of fairly crude execution; both are characteristics seen here. Earlier wall paintings often used vegetation as a decorative border motif as well. In comparison, later paintings were more typically restrained to panels, increasingly architectural in theme and more competently executed. All styles of decoration would have been relatively expensive and placed within the most socially significant areas of the building (Davies 2008) – it is notable that these paintings are located directly above the bust of Charles, on the floor below.

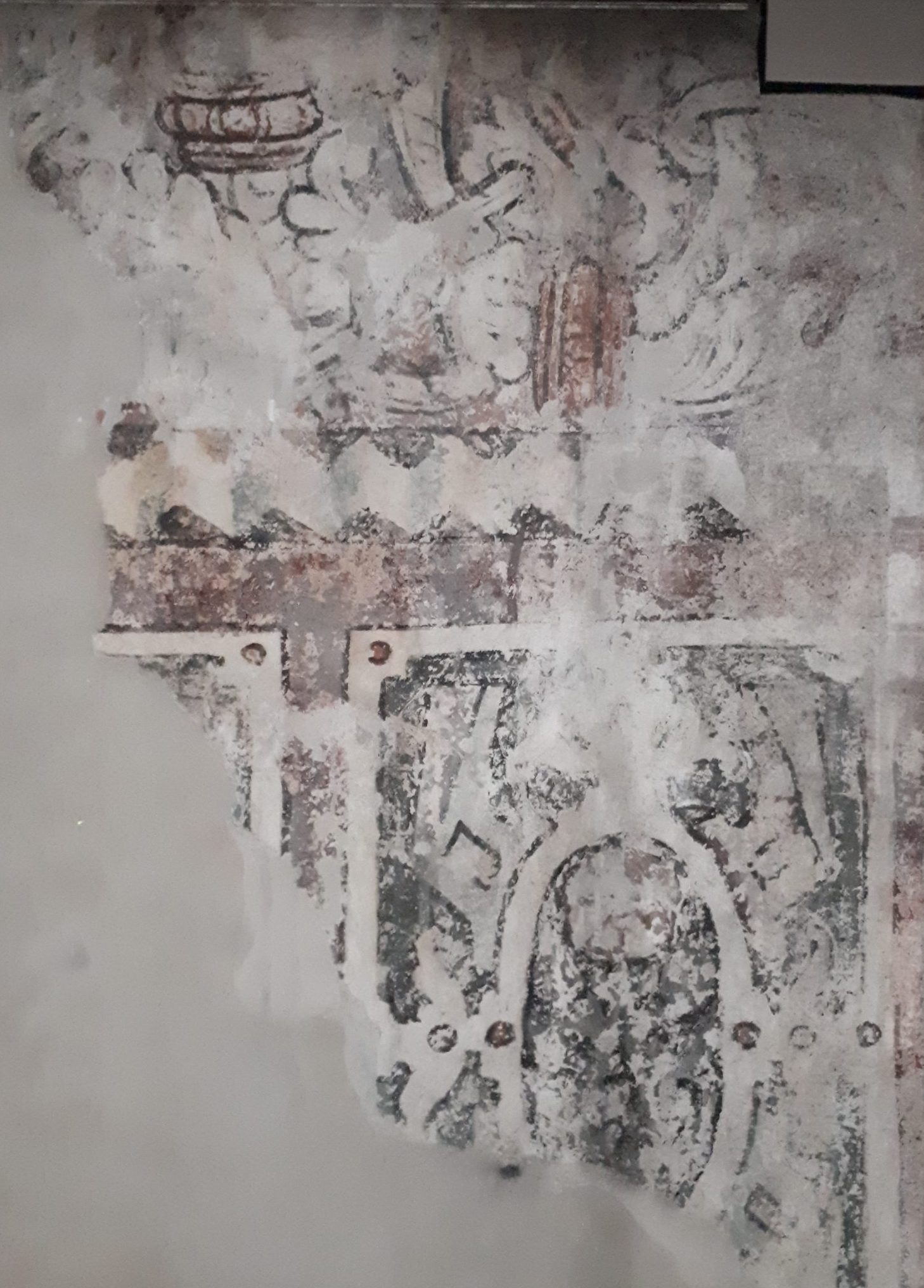

After a period of extensive and painstaking conservation the wider motif became visible within parts of the room, showing a high degree of vegetation in the borders surrounding panels, which was intended to mimic wood panelling with a dado rail above. To a large degree this confirmed our earlier speculation on the style of the paintings and putting them broadly into the 1575-1625 date range. A further interesting feature is a faded “fleur de llys”. Perhaps this is evidence of royalist leanings in the owners prior to the later bust of Charles? It should not be forgotten that the traditional home of the House of Tudors was at Raglan Castle, 10km to the south west.

The date range of these paintings also overturns the suggestion that the Kings Head was built after the Civil War on in-filled defences. A detailed survey of the structure further supports an earlier date for the building, as a potentially late medieval phase of the timber frame was identified. Further glimpses of this possible medieval building remain hidden, boxed in by later walls and their coverings – understanding the building’s full character must await a future opportunity.

|

|

|

The wall paintings as conserved, with a faded blue fleur de llys at the bottom (righthand photo). |

|

Thank you to Wetherspoons who commissioned us to work on the wall paintings and ensure they are recorded and understood.

References

Cornah, T 2017 Building recording at the Kings Head, Monmouth, Monmouthshire, Worcestershire Archaeology, Worcestershire County Council, report 2454

Davies, K 2008 Artisan Art: Vernacular Wall Paintings in the Welsh Marches, 1550-1650

Post a Comment