Adding a New Layer: 20th Century Heritage in Worcestershire – Education

- 23rd September 2020

Remember your schools? Sites, buildings, structures and features relating to the provision of knowledge and skills are one of the most distinctive and often innovative examples of 20th Century architecture, particularly in terms of how their planning expresses developing ideas about children and society.

Over the past two years Worcestershire’s Historic Environment Record has been working to identify, record and better understand the significance of 20th Century buildings and public places across the County. Many more await discovery and assessment!

Funded by Historic England, this project has also aimed to strengthen the public’s awareness and appreciation of ‘everyday’ 20th Century heritage, its conservation, value and significance.

From County Small Holdings and Schools to Village Halls and National Chain Stores, this blog will – over the next couple of months – explore the diverse range and legacy of our 20th Century heritage and celebrate the extra layer of richness it brings to both our lives and landscapes.

Late 19th century educational reform laid the foundation for mass education and Local Education Authority (LEA) school boards with responsibility for educational provision, including school building. State-funded education, as opposed to that sponsored by churches, charities or private benefactors, became predominant ‘leading to one of the most important campaigns of public building ever undertaken in the country’ (Historic England, 2017, 3). The drive for higher standards of education, which was supported by late 19th and early 20th century campaigns for more widespread social reform, gradually raised the standards of school building.

Late 19th century Board Schools, with their characteristic gables and high roofs, incorporated large windows and more spacious workspace, although came in a variety of designs.

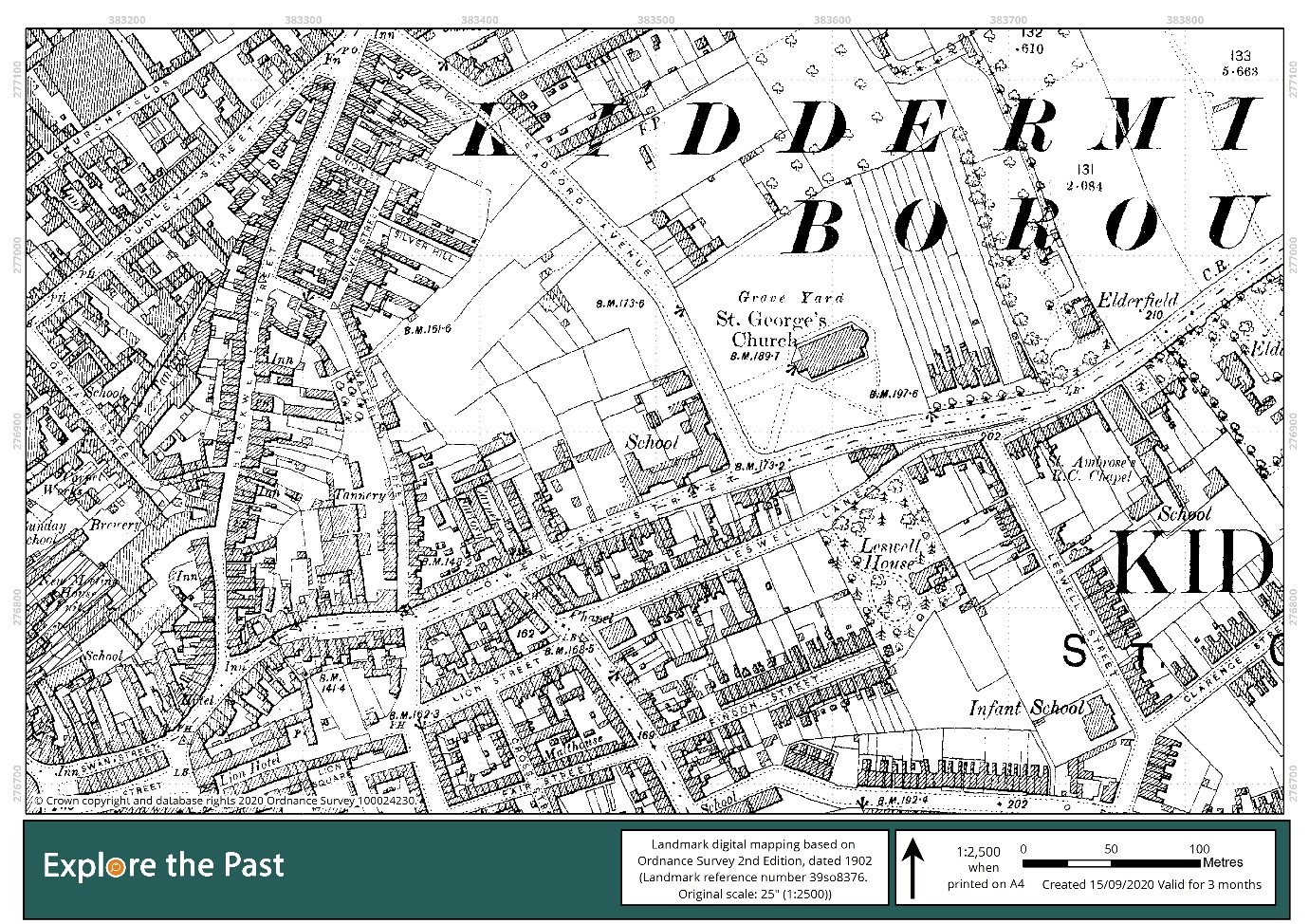

Coventry Street Board School in Kidderminster (in the centre of the map) was one of several Victorian Board Schools in the town. Only one building, now a Children’s Centre, remains extant; it is recognised as a building of local significance on the Kidderminster Local Heritage List. An old photograph of the school can be seen here on the Kidderminster Civic Society website.

From the 1870s school building adopted greater standardisations in design. The Queen Anne Style, with its distinctive red brick form and decorative detail, was widely adopted and greater thought was given to lighting and ventilation. Some school boards began to experiment with separate classrooms with a central room or ‘hall’ – a plan form which came to dominate school design up until the 1920s (Harwood, 2012, 39) – and many also provided special schools or blocks for disabled or ‘disturbed’ children (Harwood, 2012, 46).

Early 20th century designs began to take more account of educational theory—including designing from the point of view of the child—as well as good hygiene, and schools began to move away from the central hall plan towards individual blocks—often in a neo-vernacular design— around a central courtyard. Cross ventilation and covered or open verandas encouraged fresh air and exercise (English Heritage 2010, 53).

Holyoakes Field First School and Nursery in Redditch was built in 1913 to a design by A.V Rowe, who also designed the Grade II listed Parkside High School in Bromsgrove. © WCC

Trinity High School (formally County High School) in Redditch, was completed in 1932. Designed by H.W. Simister of Birmingham the original school consists of a brick building centred on two courtyards, lined with cloistered walkways. © Trinity High School

Open Air Schools, built to combat tuberculosis, became more popular from the 1930s to 1950s, promoting fresh air, vigorous exercise, rest and a wholesome diet as well as outdoor learning opportunities. From 1925 the Birmingham Local Educational Authority began opening Open Air schools, including in north Worcestershire. Cropwood Open Air Residential School in Blackwell, with its farm, open air swimming pool and sleep-time garden, was gifted by Barrow and Geraldine Cadbury to the city of Birmingham in 1925. Hunters Hill Open Air School, built on land near Cropwood, opened in 1933. The classrooms and dormitories were built around a square courtyard onto which opened wooden verandas. In 1980 Hunters Hill amalgamated with Cropwood; the two sites still function as a school for children with special educational needs. Skilts Open Air School in Redditch was the last of Birmingham’s Open Air schools. Opening in 1958, in a 16th Century manor, the school continues to function today. Rose Hill Open Air School in Worcester opened in 1926, on Windermere Drive in Warndon. It later became a special school before closing in 2007. Regency High School now occupies the site.

The rising post-war birth rate, coupled with the creation of many new communities as part of the housing programme, the wider movement for social architecture and the extension of the school leaving age to 15, led to a further explosion of public school building in the 1950s and 1960s. Limited budgets and stringent building regulations stimulated simple, practical, International modern designs and the use of lightweight, prefabricated steel frames, asbestos and glazing, which a young generation of architects in private practice had started to tentatively explore pre-World War II, albeit in less standardised forms (Harwood, 2012, 68 and 69).

Originally built as a Secondary school in the 1950s, Sion High School in Kidderminster later became a Middle School. It was built to the designs of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect who completed the Grade I listed Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool. Designed around a grassed quadrangle, it represents a continuation of the pre-war International Style in its strong and modular horizontal form. After being derelict for approximately 10 years the site was recently redeveloped. © Paul Collins

In the post-war period, school design was widened to include the work of architects with a national portfolio. Two notable examples in Worcestershire were Birchen Coppice County Primary School, Kidderminster (1953), and Bewdley County Secondary School (1955), which were both the work of the Modernist firm of Yorke Rosenberg & Mardall, whose other works include Gatwick Airport and the University of Warwick. From the late 1950s onwards open plan interiors were favoured for Primary and Junior schools, particularly those with mixed year classes. Classrooms were built, often in a circular plan, around a shared activity area, such as a library. Pavilions were erected to support outdoor learning (Harwood, 2012, 80). As well as private architectural practices, municipal architects have also left an impressive legacy of schools.

The Chase High School in Malvern opened as a Secondary Modern in 1953 and incorporates an earlier communal building built as part of a large purpose-built engineering unit for the Telecommunications Research Establishment. © WCC

The Edinburgh Dome at Malvern St James Girls’ School is Grade II listed for its rare method of concrete construction. Named after the Duke of Edinburgh, who opened the building in 1978, the dome was designed by Michael Godwin and is a ‘parashell’ concrete structure. John Faber of Oscar Faber acted as the engineer. The ‘parashell’, was invented by Italian, Dante Bini, in 1967. The construction company Norwest Holst bought the sole rights to market the system in England but only two were ever constructed. The building was nationally listed in 2009 after being threatened with demolition. © Historic England Archive DP138177

Many newly constructed post-war schools embraced the use of public art in communal areas. The Society for Education in Art argued that art had a vital role to play in education and the learning environment. The Bewdley County Secondary School which was designed by Yorke Rosenberg & Mardall, in the modern style, opened in April 1956, and was decorated with a wall mural by the celebrated English print maker, painter and art teacher Michael Rothenstein. A photograph of the mural is part of a collection of photographs showcasing the school, taken by Reginald Hugo de Burgh Galway, in 1955, that are now part of the Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

Few schools were built in the 1980s and 1990s; a drop in the national birth rate and changing socio-economic factors, encouraging the adaptation of existing buildings and the addition of new blocks to existing schools, to meet single use needs such as Science, Modern Languages and Drama. Late 20th and 21st Century initiatives to modernise and improve the environmental credentials of schools—including the national ‘Building Schools for the future’ programme has led to the loss of many late Victorian and 20th Century school buildings. The sale of school playing fields, often to raise revenue for refurbishment or re-development, is also of increasing concern.

The Robbins Report in 1963 resulted in the building of many more universities, colleges of technology and further education. These were added to earlier generations of mostly Domestic Revival and neo-Georgian buildings including the ‘red brick’ universities dating from the end of the 19th Century. They include some striking examples of modernist architecture by leading practitioners on the national and international stage, universities being particularly distinctive in this respect. The ‘modern’ library, as we understand it today, was also a development of the 20th Century. The 1919 Public Libraries Act gave County Councils the power to become library authorities, making provision in rural areas more realistic, albeit this provision was generally small scale or even mobile. Libraries were often combined with a museum and gallery or later integrated within larger Civic Centres, which incorporated a wide range of local services and facilities at the heart of post-war re-developed town centres or newly developed suburbs. Neo-Georgian styles were favoured in the Inter-War period – but became less formal as provision for children increased – with post-war libraries embracing simpler European modern styles and a greater flexibility, with space for exhibitions and events, and tables and chairs for reading in the library.

Worcester College of Technology buildings, designed by Richard Sheppard, Robson & Partners, in 1960-1973, are recognised on the Worcester City Local Heritage List. © Philip Halling, licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Redditch’s Library, designed by the John Madin Design Group of Birmingham, is described by Pevsner and Brooks (2007, 90) as the best 20th Century building in town.

Historic England Guidance

Education Buildings: Listing Selection Guidance. (2nd ed. 2017) [Accessed 2018 – 2019]

Harwood, E 2012 (Reprint) England’s Schools: History, architecture and adaptation. Swindon: English Heritage

The English Public Library 1945-85 (2016) [Accessed 2018 – 2019]

Local Heritage Lists

Kidderminster Local Heritage List (n/k), Wyre Forest District Council [Accessed 2019]

Worcester Local List of Heritage Assets (2017), Worcester City Council

Post a Comment