Darwin and The Water Cure – Part 2 Darwin, Malvern & Barnacles

- 1st September 2020

Did you know Charles Darwin had links to Malvern? In this three part blog we look at his visits and connections to the water cure using some of the books and information in our collections.

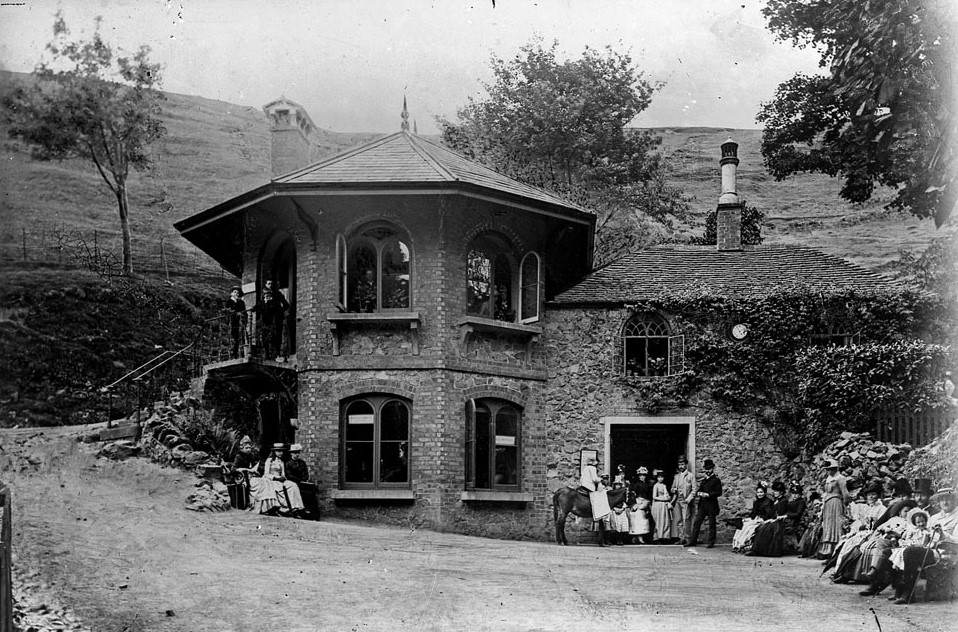

Whilst Charles Darwin was undertaking treatment for the water cure, he and his wife Emma explored Malvern and the wider countryside with their children. One of the popular places to visit in Malvern was St. Anne’s well. As Rebecca Stott writes in Darwin and The Barnacle ‘Mrs Thorley, the Governess will give the older children their lessons and has then promised them a donkey ride today with Emma, over the hills to St. Anne’s Well, the cold-water spring.’ (Stott, 2003) Henrietta (Etty), the Darwins’ second eldest after Annie also recalls in an account here how ‘I remember the little china mugs we got at St Anne’s Well & drinking the water at the well.’

Glass Plate Negative of St. Anne’s Well, early 20th Century © WAAS

The journalist Joseph Leech (1856) describes the scene vividly at St. Anne’s Well:

‘The Water itself, which dribbles away into a carved stone basin at the rate of about a glass a minute, through a kind of penny whistle placed in the mouth of a pleasant dolphin, is quaffed by crowds in a little house which is half a peddlar’s shop and half a pump room, attached to a cottage where knives and forks are hired out to tourists, and kidney surreptitiously grilled between meals for hungry patients under water treatment.’

Since at least 1817 donkeys were used to carry visitors up the hills and by 1852 there were numerous donkey hire stands. One particular donkey named Old Moses carried a young Princess Victoria to St Anne’s Well where she officially opened a new path from Nob’s (now St Anne’s) Delight to Foley Walk. As shown below, whilst donkeys are noticeably absent today, the scene at St. Anne’s relatively unchanged, though the basin where the mineral water flows into is no longer drinkable.

Image of St. Anne’s Well, July, 2020 © Anthony Roach

During their stay in Malvern, their son William went for lessons with a local clergyman, and there were dancing lessons on Friday for the children. Emma and Annie shared a love for the music at Malvern with weekly piano and orchestral recitals, jaunty polkas and waltzes played in Dr. Wilson’s ballroom (Stott, 2003). Whilst Darwin was taking the cure, he did spend time with his children as George recalls a visit with his parents to what was probably Henry Lamb’s Royal Library and Bazaar which sold fancy items, books, stationery with a music saloon with pianofortes for hire and a reading room where he says ‘They bought me a little jingling organ which made a twanging with wires stretched inside.’ (Keynes, 2001). Annie followed her father’s treatment with interest and Darwin’s letter to Susan (written in Emma’s hand) says ‘Annie was telling Miss Thorley all her Papa had to do about the water cure & how he liked it’ “And it makes Papa so angry”.

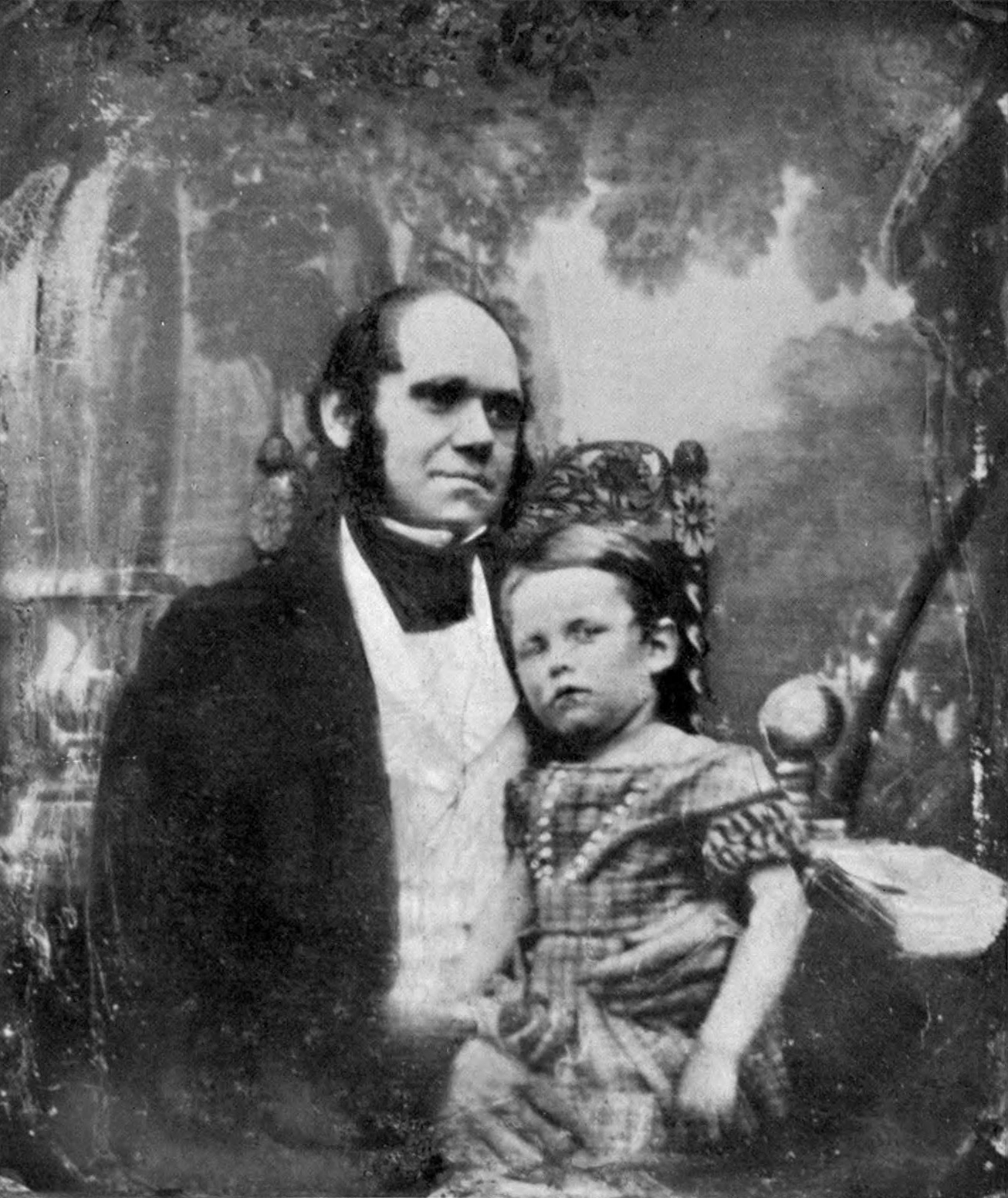

Daguerrotype of Charles Darwin and William Erasmus Darwin taken in 1842

Henrietta (Etty), the Darwins’ second eldest after Annie who was five, years later recalls how many entries in Emma’s diaries show how suffering her father’s state had become and writes ‘Emma’s diary has an entry, “29th March I went to Perristone.” ..her visit must have been a great pleasure as well as change in her home-keeping life. My father’s health now quite unfitted him for visiting or for her to leave him with any comfort, so that practically she never left home. (Litchfield, 1904, p124-5).

Daguerrotype of both William and Henrietta (Etty) Darwin both taken in 1849

Darwin felt he wore Emma down with his ills as he writes in a letter to her on 17th November 1848:

My own dear wife, I cannot possibly say how beyound all value your sympathy & affection is to me.— I often fear I must wear you with my unwellnesses & complaints.

Your poor old Husband C. D.

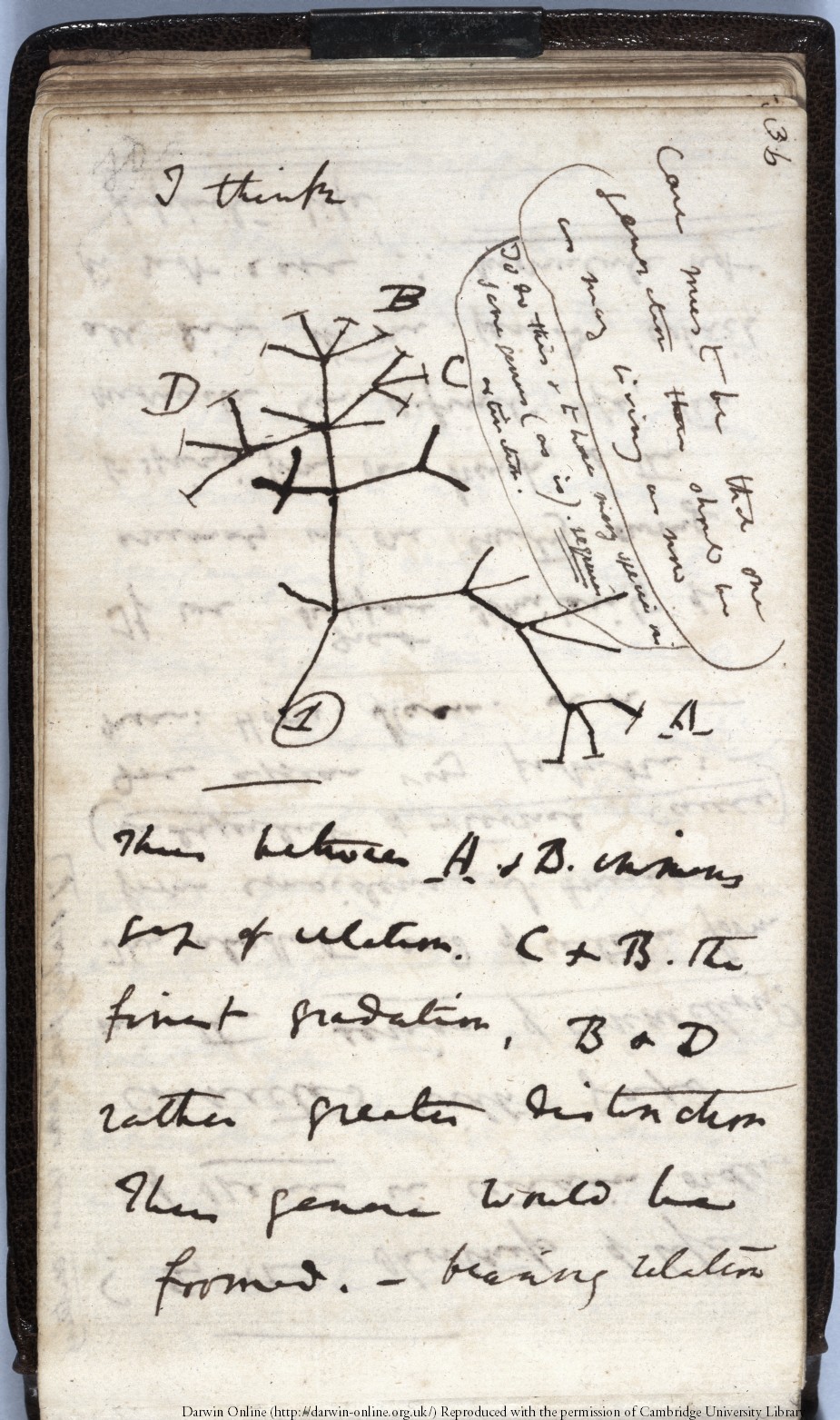

Charles Darwin’s now infamous sketch of an evolutionary tree and the words ‘I think’ taken from Notebook B: [Transmutation of species (1837-1838)]. ‘commenced. . . July 1837’ from Darwin Online

Two years before, Darwin had made an important decision. Since 1837 he had been working up a sketch of his species theory which he had begun to formulate on The Beagle. Upon his return he had corresponded with many scientists and naturalists to describe his many specimens in writing up his notes and observations of the voyage. Hardly a sketch, it was an immense 231 pages and amounted to eleven simple words: Species are mutable. Allied species are co-descendants of common stocks. This was a hypothesis; an idea in embryo and in order for his ideas to be accepted they had to be rooted in everyday things: common sense; empirically observable truths (Stott, 2003).

In a letter to his naturalist friend, the botanist Joseph Hooker in 1844 (who later read his sketch) he writes: ‘At last gleams of light have come, & I am almost convinced (quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable.’

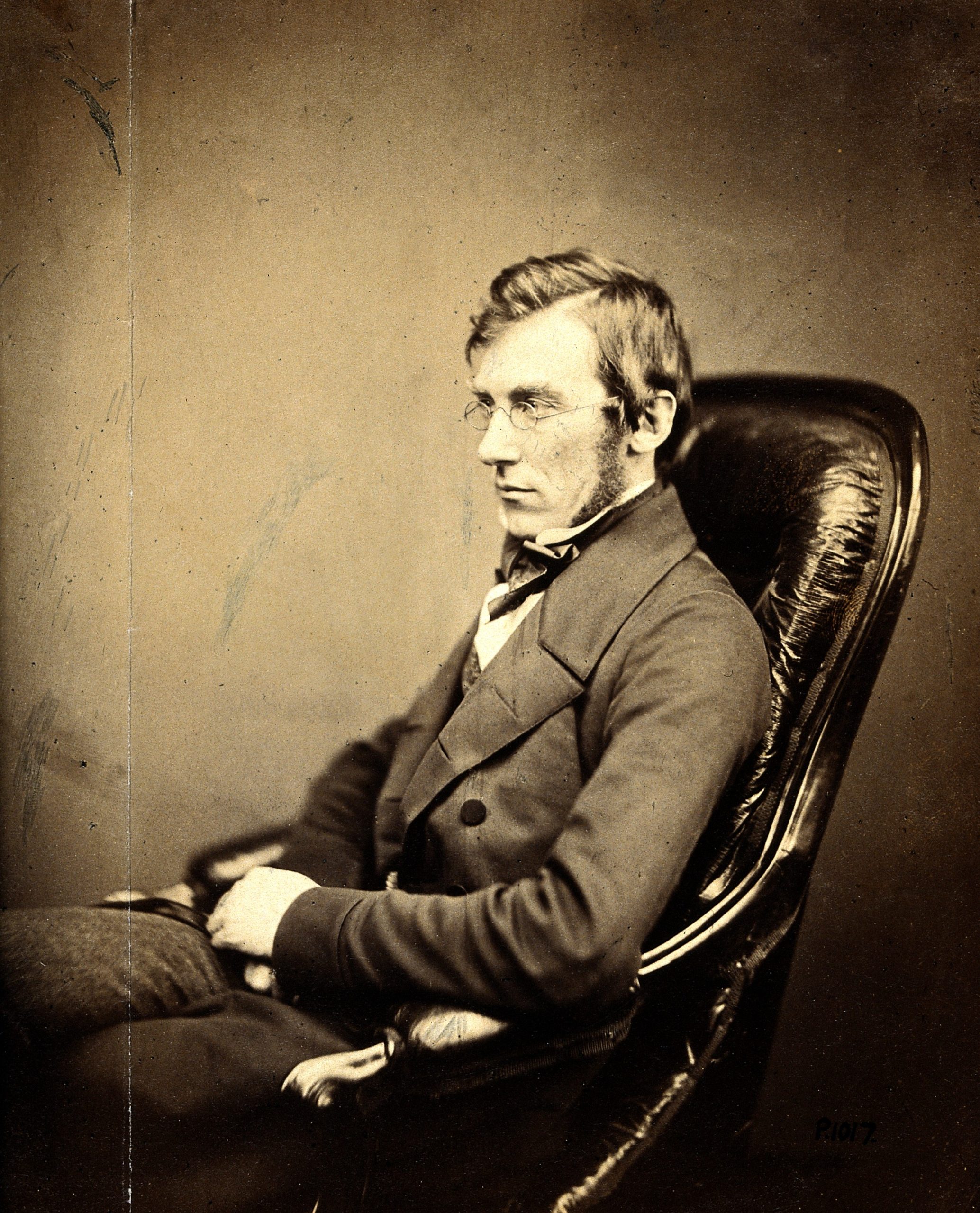

V0026577 Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images http://wellcomeimages.org Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons

That same year, Darwin wrote a letter to his wife Emma, who in spite of concern for his religious salvation and waning religious belief remained supportive of her husband’s work throughout his life, helping to facilitate his scientific work and correspondence. In this affectionate letter he entrusts Emma, along with friends to ensure his species theory would be published even if he died suddenly.

Poised to publish his findings that year Darwin was acutely aware of the impact of what some would argue ‘heretical’ ideas, both within the scientific establishment and when belief in God and the divine creation of the Earth were the bedrock of society. Apart from Hooker and Charles Lyell (whose book ‘Principles of Geology’ so inspired Darwin’s ideas during the Beagle Voyage but it is unclear to what extent Lyell knew about ‘Natural Selection’) the only other person he shared the detail of his big idea (he often cloaking the term in letters to others simply as his ‘species work’ or work on ‘varieties’) was his beloved wife Emma, herself a fervent Christian. Emma wrote to her husband about his religious doubts in 1839 fearing his work may lead him to discount what cannot be proved and advised that there are some things which “if true are likely to be above our comprehension”.

Front page of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation by Robert Chambers 1884

The publication of Robert Chambers’ Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, however, threw a spanner in the works. The anonymously authored book which Rebecca Stott describes as ‘telling the story of the Earth from its beginning, spinning through time and space….from simple marine invertebrates up through fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and man. It was a sensation. […] ‘We started out as fish?’ people were asking. How ridiculous. How fascinating.’ (Stott, 2003) You can find out more about society’s reaction to Chambers’ book by reading James A. Secord’s book Victorian Sensation available in our Main Collection at The Hive under 306.450941 SEC.

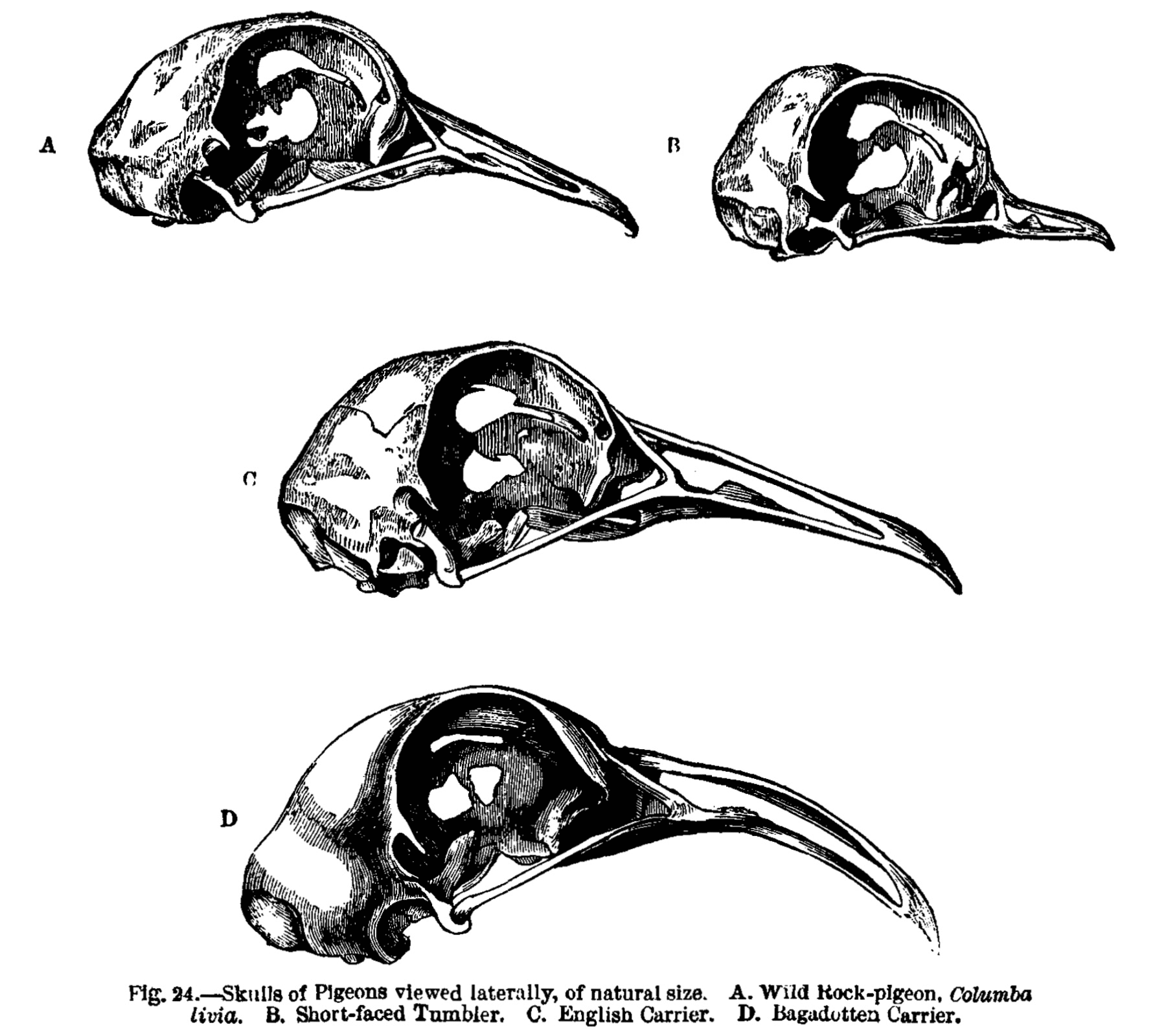

While people from across society discussed its implications, Darwin was concerned this book would supersede his theory, but upon opening it realised it had been a botched job, as he says in a letter to his friend Hooker ‘the writing & arrangement are certainly admirable, but his Geology strikes me as bad, & his zoology far worse’. It was savaged by commentators at the time and judged dangerous by the political establishment (Thompson, in Huxley, 2007). It was a blow for Darwin, some even attributing the book to him, who was both ‘flattered and unflattered’ as he writes in his letter of April, 1845 to his cousin William Darwin Fox. Darwin recognised the need to accumulate clear evidence and one way he did this was breeding pigeons to demonstrate artificial selection in contrast to ‘Natural Selection’. In just one of many experiments that Darwin undertook he enlisted Fox’s advice on pigeon breeding as shown in his letter of March, 1855.

Pigeon skulls, as drawn by Charles Darwin, taken from Darwin, Charles (1883) [1868] “Pigeons” in The Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication

Many have theorised about Darwin’s illness, some suggesting it was, in part, psychological. Randall Keynes explains in ‘Annie’s Box’ that the burden of ‘Origins’ contributed to his ill health and Darwin himself admitted it was ‘the main part of the ills which my flesh is heir to’ and states that ‘Charles and Emma understood that his health was often directly affected by his state of mind. When he was worried or upset about something, he could not control his mental turmoil. Underlying all his other concerns were his anxieties about the theory of evolution, the strain of living with the secret and his anticipation of the attacks when he announced it and people saw the implications (Keynes, 2001).

Portait of Emma Darwin by artist George Richmond, 1840

In 1846, Charles shelved plans for publication. Some historians have argued the reaction to ‘Vestiges’ was a disaster for Darwin. However, it gave him an opportunity as Keith Thompson explains in The Great Naturalists. Darwin understood that for his ideas to be accepted, he realised the importance of carefully building evidence and a constituency among authoritative people like Charles Lyell, Joseph Hooker and Thomas Henry Huxley beforehand (Thompson, 2007). His ideas must be backed up with sound scientific rigour, something that critics argued was missing from ‘Vestiges’. Darwin had agreed with his friend Hooker in a letter to him on 10th September 1845 ‘How painfully (to me) true is your remark that no one has hardly a right to examine the question of species who has not minutely described many.’ Whilst Hooker had not directed this accusation at Darwin, he felt that his own scientific credentials were in question. He had not ‘minutely described many’ himself so why should anyone take his views on species change seriously?

So it was in 1849, Darwin, in very poor health, was continuing his treatment from Dr. Gully, a man who he was a contemporary with at Medical School in Edinburgh. With his species theory firmly locked away, though not far from his mind, for the past three years Darwin had devoted himself to the classification of barnacles. Ironically, whose interest and attention was drawn as a Medical student in Scotland hunting for marine life in the Firth of Forth (Jones, 2009).

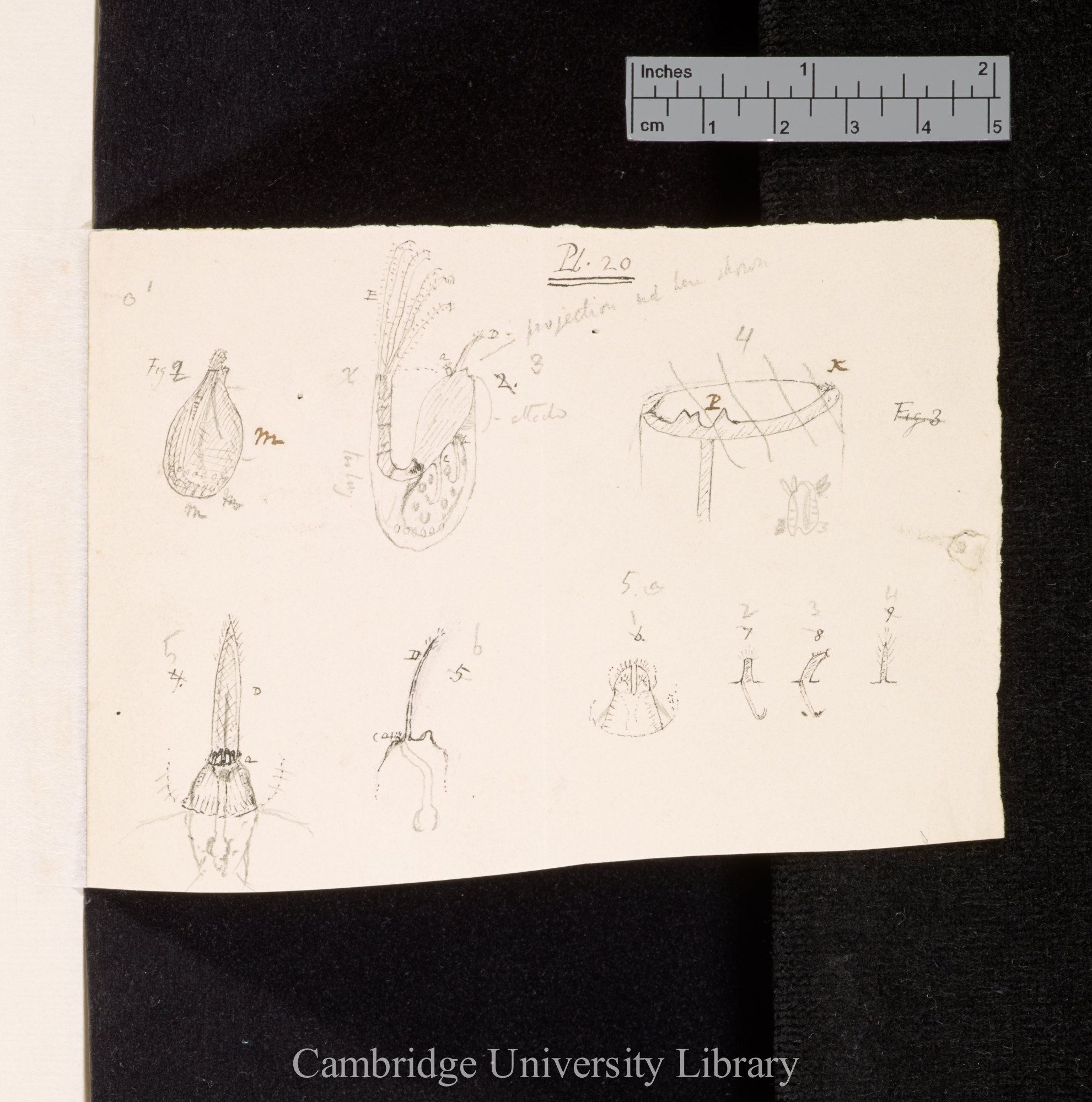

Darwin’s drawing of “Mr. Arthrobalanus” a barnacle observed by Darwin on board H.M.S. Beagle from one of his notebooks listed as ‘Shells & post Beagle zoological materials’ MS-DAR-00029-00003-000-00272.jpg (DAR 29.3, p.72ar) ‘Reproduced by kind permission of Cambridge University Library’

It was the chance discovery during the Beagle voyage on the shores of the Chonos archipelago off the Coast of Chile of a very unusual soft-bodied creature drilling into a Conch shell that would inspire Darwin. At first glance he thought it a worm, but it’s naked body belied a truth that on close inspection revealed it was indeed a Barnacle, without a shell, yet strangely similar to those found on the shores of Scotland (Jones, 2009). He describes it in detail in one of his Beagle notebooks here.

Darwin had nicknamed it ‘Arthrobalanus’ and decided that he would trace its relationship and evolutionary origins to species in Britain and across the world (Stott, 2003). After the study and classification of thousands of specimens collected from fellow scientists, naturalists and collectors however, he found there were lots of intermediate forms, as well as distinct, aberrant forms. He wondered, perhaps if all barnacles had descended from a common ancestor, which he had already suspected was true of all animals. In doing so he could provide further evidence to support his theory through practical zoology (Jones, 2009). Darwin could arguably then be taken seriously as an authority on the scientific stage.

Whilst Darwin wasn’t allowed to work and dissect his beloved Barnacles at this time, Darwin used his letter-writing allowance to request new specimens, so that they would arrive at Down by his return (Stott, 2003). On 6th May, 1849 he writes to his friend and former teacher John Stevens Henslow ‘my sickness much checked and considerable strength gained. Dr. G.,[…]…tells me he has little doubt but that he can cure me, in the course of time, time however it will take…‘We shall stay here till at least June 1st., perhaps till July 1st…’

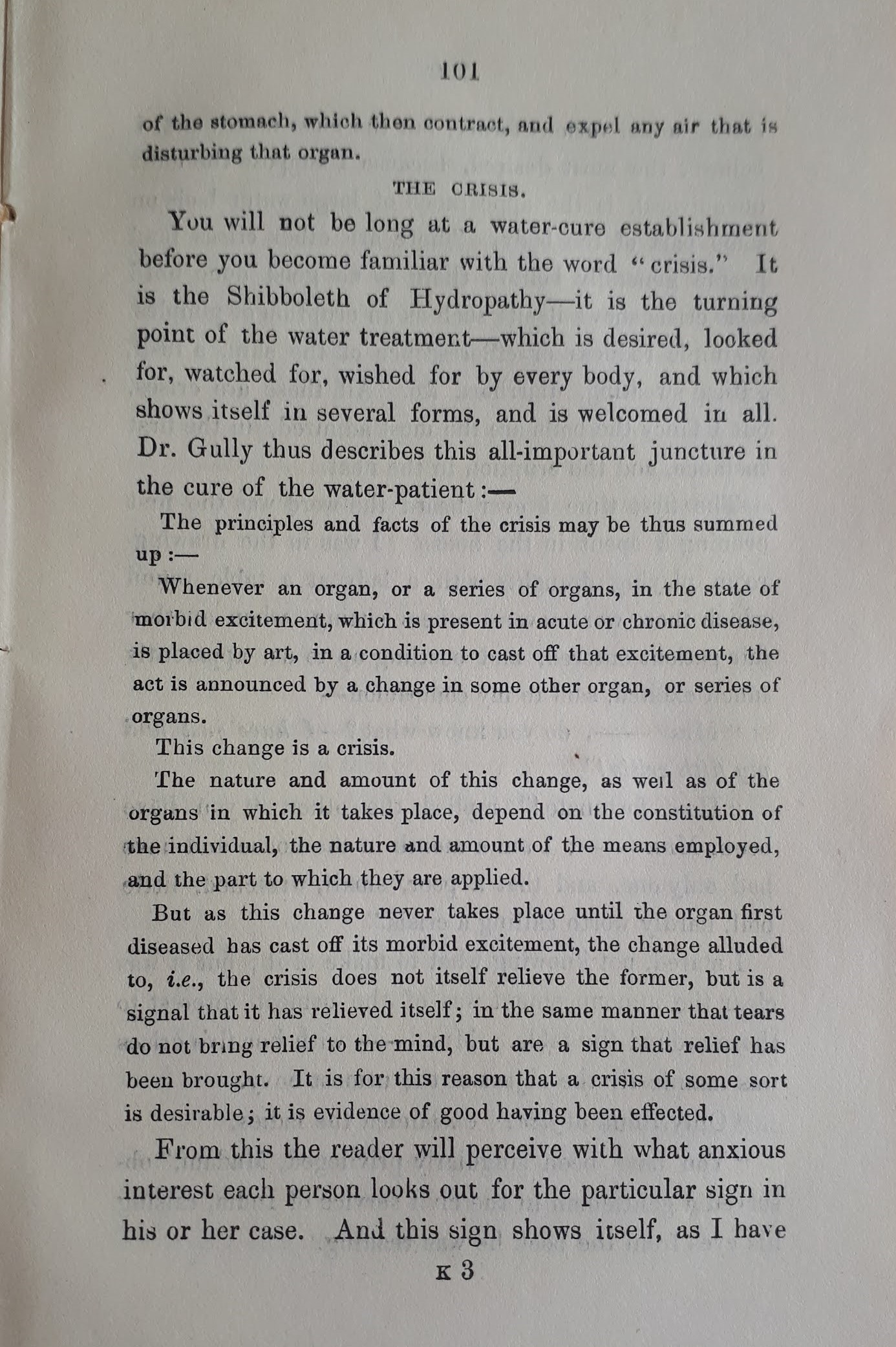

Description of a crisis in Leech’s Three Weeks in Wet Sheets (1856) available at Ref: LP 615.853

By this time, Darwin’s body had already produced a so-called ‘Crisis’ – a reaction to the treatment such as ‘an eruption of pimples, a simple redness….a rash…’ and much discussed and desired by patients. A page from Joseph Leech’s book Three Weeks in Wet Sheets describes in Gully’s own words what The Crisis meant and how a woman proudly exclaimed ‘do you know what? – I have just had my fifth crisis!”…. “You have been singularly privileged, Madam” observed a gentleman..’

Indeed, in a letter to the astronomer John Herschel on 6th June 1849, he highlights his recovery, alongside other matters, including the ‘Crisis’: ‘I have been here for three months under Dr. Gully & the Cold Water Cure, which has had an astonishingly renovating action on my health; before coming here I was almost quite broken down, head swimming, hands tremulous & never a week without violent vomiting, all this is gone, & I can now walk between two & three miles.’

Darwin was now apparently on the road to recovery.

Further Information:

The Darwin Correspondence Project: https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/

Darwin Online: http://darwin-online.org.uk/

The Water Cure in Chronic Disease

Author: James Manby Gully. 1851. – Available at Level 2: Local Lending – L 615.853

Three Weeks in Wet Sheets

Author: Joseph Leech. 1856. – Available at Level 2: Palfrey Collection – 615.853

Annie’s box: Charles Darwin, his daughter and human evolution

Author: Keynes, Randal. 2001. – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference – B DARWIN,C

Darwin and The Barnacle

Author: Stott, Rebecca. 2003 – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference

Darwin’s island : the Galapagos in the Garden of England

Author: Jones, Steve 2009. – Available at Level 3: Main Collection – 576.82 JON

The Great Naturalists

Author: Huxley, Robert, 2007. – Available at Level 3: Main Collection- 570.922

Post a Comment