Plague in Worcester 1637

- 9th September 2020

When lockdown started in March, Dr Pat Hughes, local historian and regular in the archives, looked into a previous epidemic, the plague of 1637. She probably knows the city archives better than anyone, an even without access to the original documents she still was able to write and send us this fascinating look at what happened in the city.

In response to the coronavirus, and in a very uncalled for reference to my age, one of my granddaughters suggested that I should get out my plague mask! It prompted me to look again at the great plague outbreak in Worcester. While listening to endless news bulletins I thought I saw some parallels to behaviour in an earlier epidemic.

Although the national outbreak took place in 1665, Worcester suffered its own major plague epidemic in 1637. There had been spasmodic episodes in the 16th century and the early decades of the 17th century. The 1637 plague does not appear to have affected the surrounding towns; both Droitwich and Tewkesbury were in a position to send aid to the city.[1] (See below)

The measures put in place for these episodes provided a framework for the much more serious situation in 1637. By this time isolation attempts were in place, and some financial arrangements to help, via taxation, ‘towards the reliefe of the howses now infected or hereafter to bee infected’,[2] inns were being closed; the Bell in Broad Street was closed down when the innkeeper, Mary Holder ‘having her house visited by the infection did keep the same secret without makeinge the same knowne to the great danger and damage of many people’.[3] The remaining buildings of the Franciscan friary to the east of the city, city property, which had been let to tenants, were requisitioned and used as a pest house (the city tried to retain the Friary as a workhouse after the outbreak claiming that they had spent money on it!!).[4]

All these interventions, and more, were entered in the Chamber Order Book between 1603 and 1626. I was therefore surprised to find no entries concerning the 1637 outbreak until 1638 and 1639 when a handful of references related to the epidemic.

Only when I looked at the dates of the council meetings did the reason for this become clear. Although the number of council meetings per year always fluctuated according to the business to be transacted, it is notable that no meetings took place between March 24th and November 17th.1637. The city administration was in abeyance for eight months, although the elections for civic appointments did go ahead in August.[5]

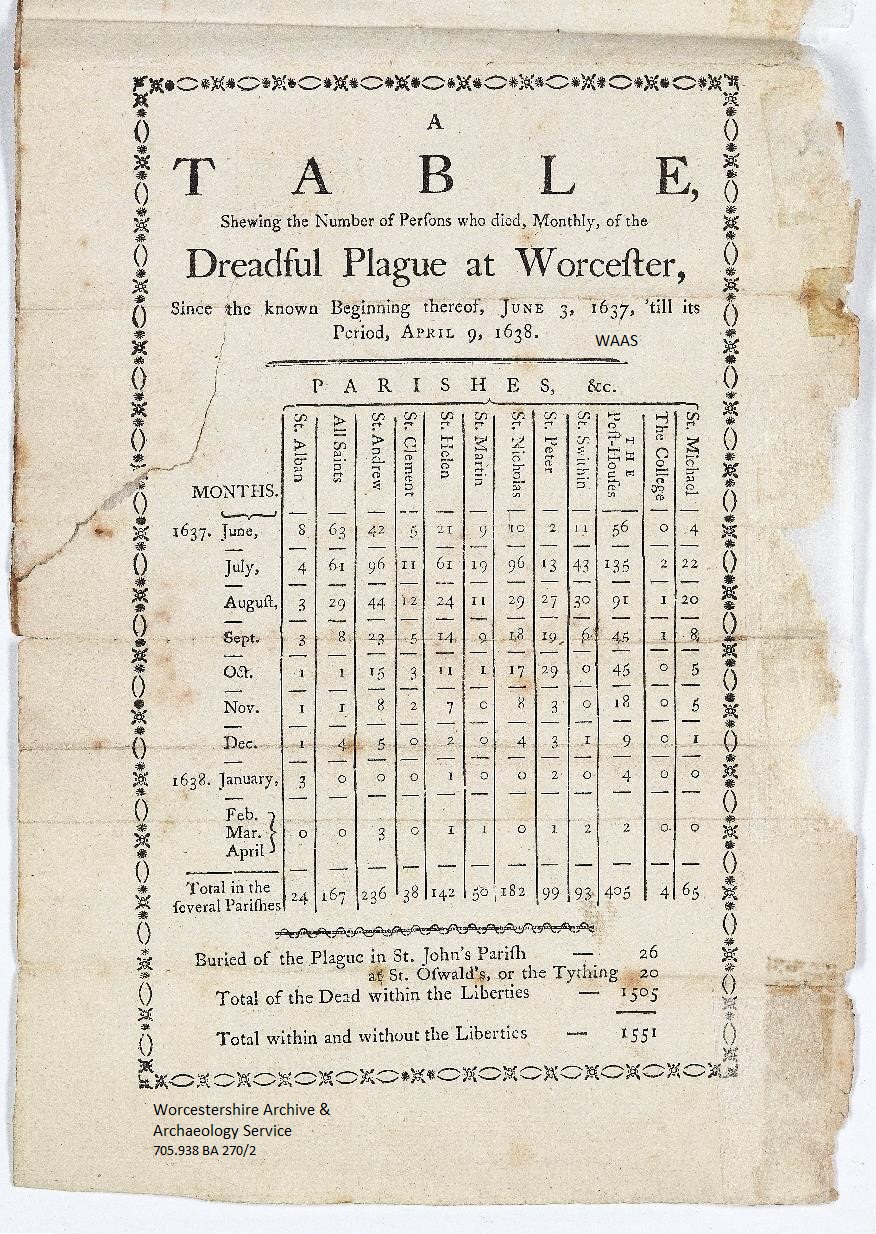

For information concerning these months we have turn to three invaluable sources. Two are contemporary pamphlets. One, by Philip Tinker, a minor canon at the Cathedral, itemises the number of deaths across the city.[6] The other by John Toy, schoolmaster, first at the city school and then at the Cathedral school, deals, in verse, with the social consequences.[7] Another source, on a scrap of paper accompanying a prayer, in the British Library, details the way the disease spread through the town.[8]

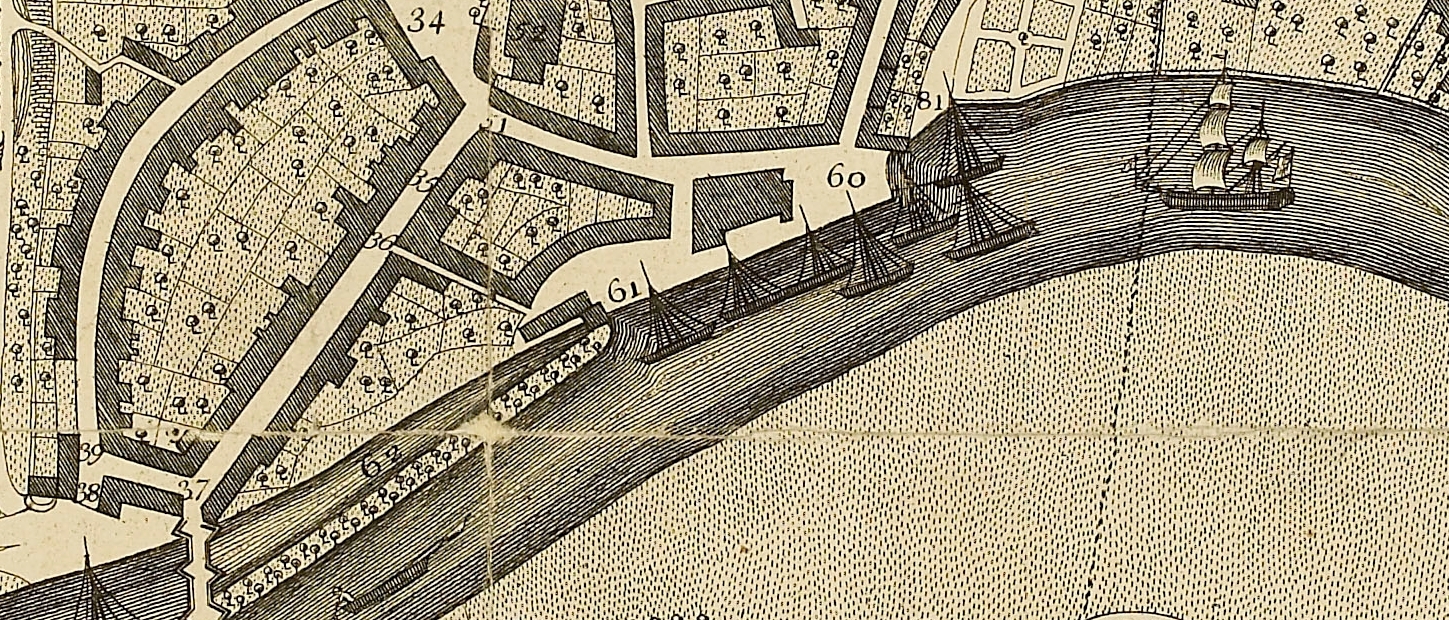

Bean’s Entry (Alley) (No.36) on Doherty’s 1741 map of Worcester. All Saints is 52, Newport St is 35. Worcester Bridge is 37, to the north of the present bridge.

It tells us that it started in Bean’s Alley, a track, lined with cottages, on the south side of Newport Street, leading to the Quay. It then spread into the city, up Newport Street and Quay Street, Cooken (Copenhagen) Street and Birdport (now under Deansway) and throughout St Andrews Parish where it was ‘so very hot … that some saye they were afraid to goe to take a bill of the dead’. It then spread first to Fish Street, then to the High Street, where it was centred on the Earl’s Post next to the Guildhall. Pump Street, the Shambles and Goose Lane (St Swithun’s Street,) were all affected and finally the houses down Sidbury and in the Frog lane (King Street and Severn Street). Most of these areas were heavily built up, with many of the once large back gardens being turned into courts of small dwellings. When the mill pond in Frog Lane was drained as part of the subsequent Civil War defences the local inhabitants petitioned that it should not be reinstated. They blamed the disease on the miasma from the pond although rats from the mill were the more likely problem.

Philip Tinker’s statistics show that the emergency probably started before deaths were recorded at the beginning of June in 1637, peaking in July/August, and lasted until April the following year, with a total of 1146 deaths in Worcester parishes alone. The earlier pesthouse had been reinstated and 405 victims died there. According to Dyer the total was probably about 10% of the population[9].. The highest incidence of plague and the highest death toll in the city itself was in the built up parish of St. Andrews, which sloped from the High Street to the river.

There is very little information about how the pesthouse functioned. It was probably no more than an isolation area with boards provided for beds. In fact during the winter there were complaints about the ‘poore people infected’ destroying drying racks in the surrounding fields to get fuel to keep warm.[10]

Just as public figures are currently affected by the virus, so the plague was no respecter of persons. Roger Seaborne, mercer, who was Sheriff in 1636[11] and Mayor in 1637 survived to serve as alderman in 1638, but his wife and family in Goose Lane (St Swithun’s Street) were infected and it is not known if they recovered.[12]

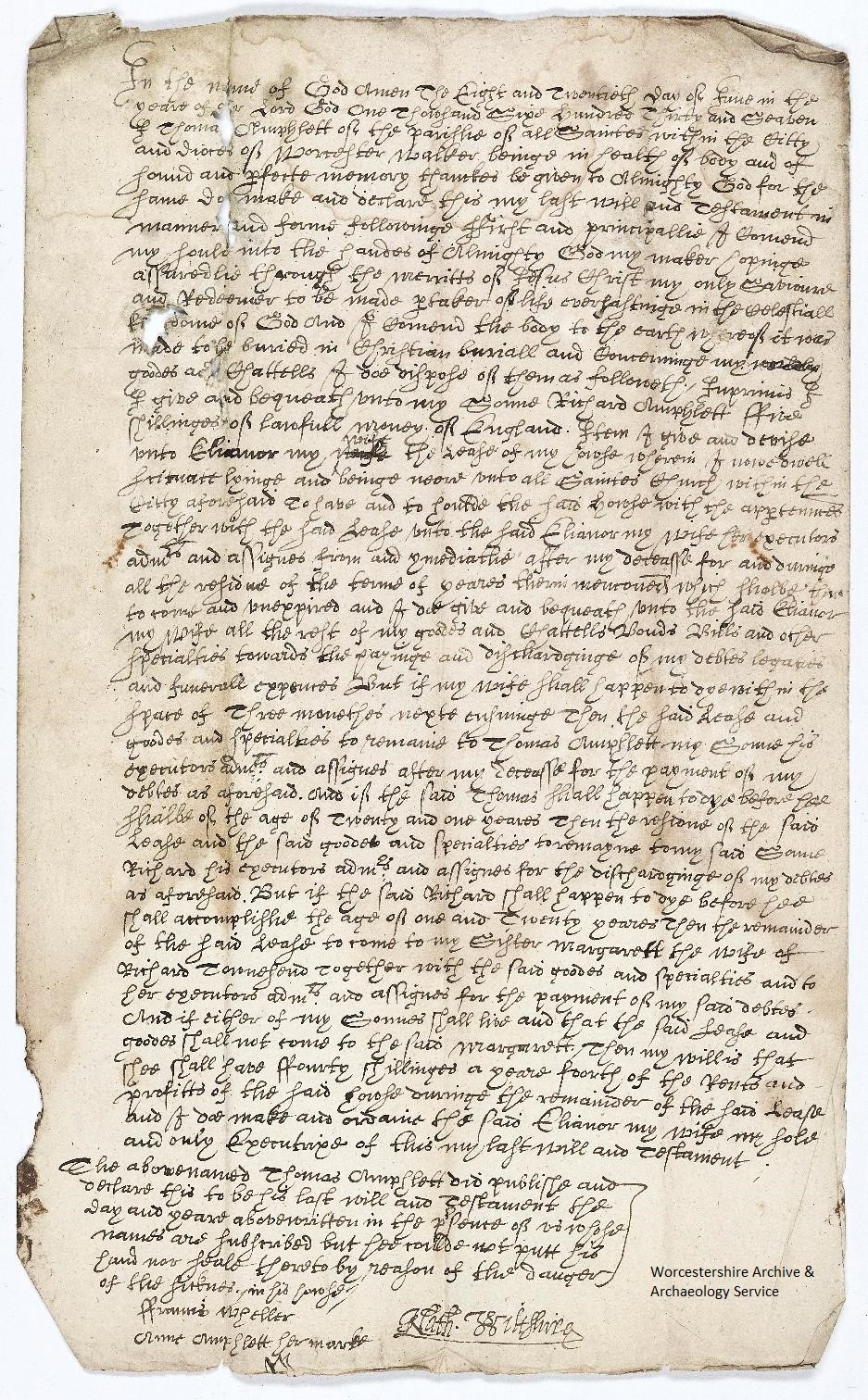

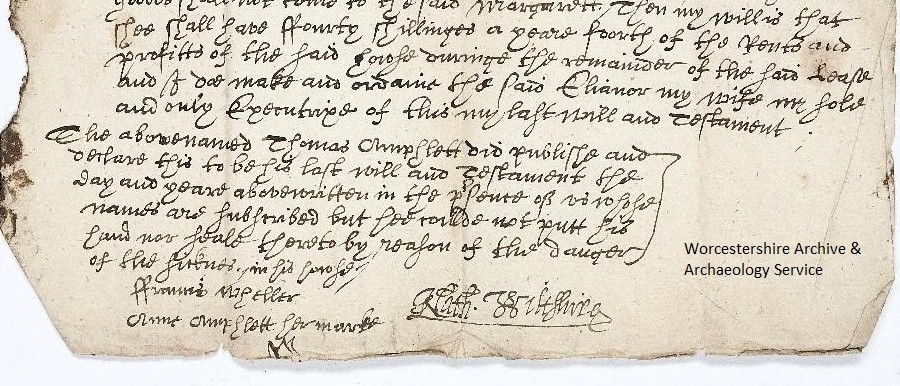

One of the most chilling documents is the will of Thomas Amphlett, of All Saints parish, a document which one can actually handle. Thomas was infected with plague and shut up in his house. He made his will, presumably via a third party, who took instructions from outside the house, but he was unable to sign it because of the contagion.

Written at the bottom of the will are these words

The above named Thomas Amphlett did publishe and declare this to be his last will and Testament the day and yeare above written in the presence of us whose names are subscribed but he could not putt his hand nor seale thereto by reason of the danger of the sicknes in his howse

Francis Wheeler

Anne Amphlett her mark[13]

Thomas Amphlett died a few days later.

The bottom of Thomas Amphlett’s will

John Toy’s Elegiac verse dealt with the appalling effect of the pestilence on the town. Looms fell silent, grass grew in the streets, those of the population, able to do so, fled. They rigged canopies over boats and slept on the river or ‘did cobble shelters’ in the fields. [14]

Nevertheless, as in the current crisis there were many acts of kindness. In his Eulogy Toy thanked the city’s benefactors. There was a real food shortage as markets were closed and fear of contagion meant that supplies were not coming in from the country. The country gentry stepped up to the mark together with towns that were not affected. In his collection of verses Toy extolled those ‘who visited the city with plenteous Almes’. Bristol, Tewkesbury and Droitwich are mentioned; together with the Bishops of Gloucester and Bristol who contributed; the Berkeleys of Spechley and Cotheridge, Lord Coventry, recorder to the city and Henry Townsend, all sent either money or cor.

As far as can be seen, the parish clergy together with the Cathedral clergy seem to have remained at their posts. Several of the Cathedral clergy appear in Toy’s verses. The Cathedral organist, Thomas Tompkins received a punning tribute. ‘According to thy tenor thou didst lend us means’.

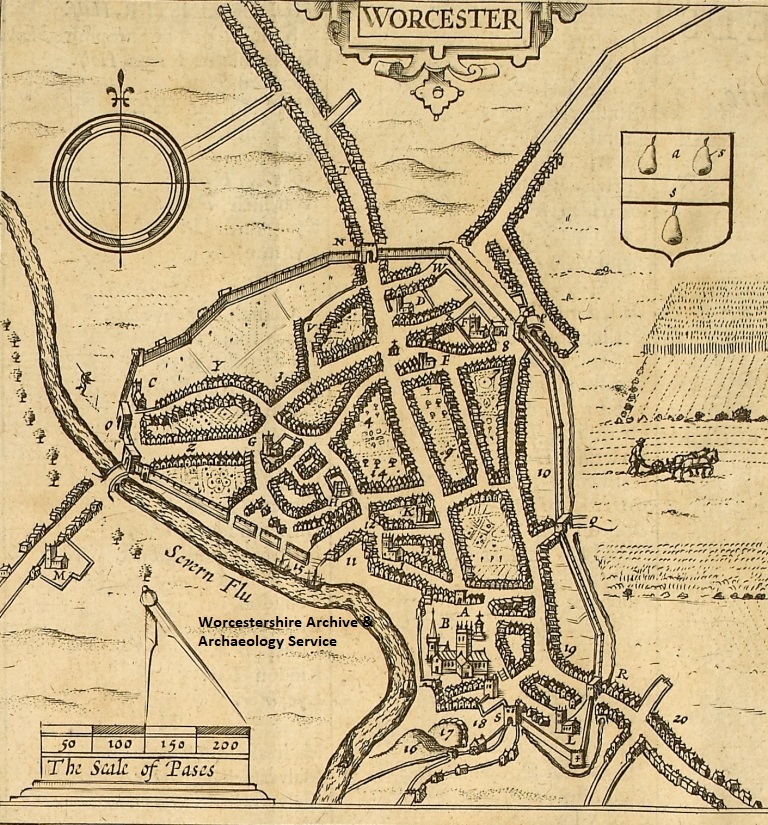

Speed’s map of Worcester 1605

By the spring of 1638 plague was on the wane; even in St Andrews parish there were only three new deaths throughout February, March and April. Council meetings recommenced and council business began once again to be transacted. Leases were granted and renewed; in July the council was even talking about rebuilding the almshouses in Dolday. Life was returning to normal.

Worcester was only marginally affected by the outbreak in 1665.

Please note that this was written when I was bored with ‘self isolating’ and with very limited resources, mainly old notes and the invaluable second Chamber Order Book edited by Shelagh Bond (WHS 1974). I have had no opportunity to check original sources and inevitably there will be mistakes and omissions.

Pat Hughes

[1] As indicated it has not been possible to check this from local parish registers etc.

[2] Shelagh Bond The Chamber Order Book of Worcester (WHS 1974) pp 80; henceforth Bond, 82,102

[3] Bond p.104

[4] TNA C8/65/97

[5] Bond pp.316 -318

[6] Tinker, Philip, Worcester’s Affliction, (J.Grundy, Worcesterc1790) available in Worcestershire Archives

[7] See John Toy, Worcester’s Elegie and Eulogy or a grateful acknowledgement of her benefactors (1638) WAAS Palfrey Library 942.44

Please note. There is a lot of detailed information in these last two works. but I have only brief notes.

[8] British Library Sloane 3723 f.67

[9] Dyer Alan, Worcester in the Sixteenth Century (Leicester 1973) p.46

[10] Bond p.321

[11] The Sheriff was responsible for the fee farm of the city, paid to the Exchequer

[12] St Swithun’s parish registers should supply the answer

[13] WAAS BA 3585 1637/1

I enjoyed this very readable account very much. Well constructed.

Thanks, we’ll pass that on to Pat

I was researching my 9th great-grandfather who died of the plague in Worcester in 1637 when I found this. So well-written and informative, and exactly what I wanted. I felt like I was there, but in a good way! Thank you, and stay healthy.

Glad you enjoyed it. Pat is a found of knowledge, knowing these sources so well, and is a great writer.