Charles Darwin & The Water Cure – Part 3: Anne Darwin, ‘Origins’ and Darwin’s return to Malvern

- 6th October 2020

Did you know Charles Darwin had links to Malvern? In this three part blog we look at his visits and connections to the water cure using some of the books and information in our collections.

Darwin returned to Down House in July, 1849 and in his letter to his cousin William Darwin Fox on the 7th writes ‘I go on with the Treatment here, just the same as at Malvern, though in a somewhat relaxed degree, so as to avoid bringing on a crisis.—2 I am building a douche, for Dr. Gully tells me I shall have to follow treatment for a year. I consider the sickness as absolutely cured.’

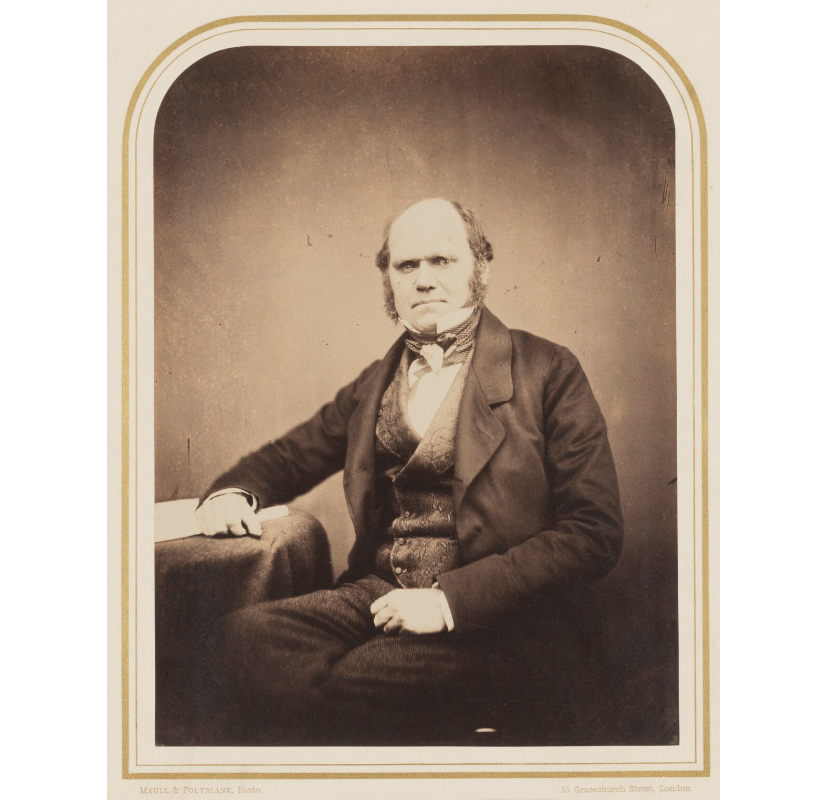

Charles Darwin, by Maull & Polyblank, albumen print, circa 1855, NPG P106(7), mw01725, © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

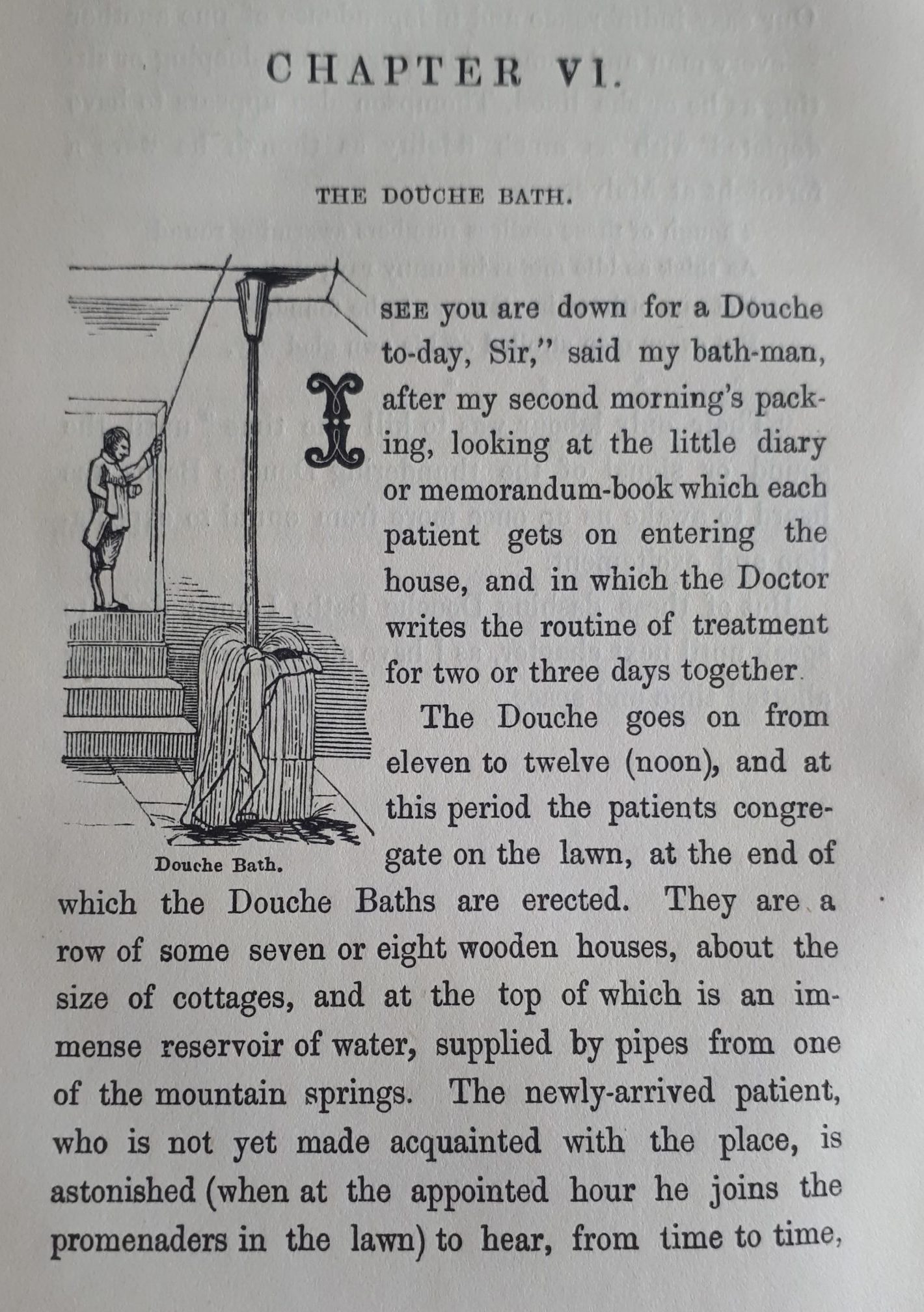

Keen not to relapse in health and following Dr. James Manby Gully’s advice Darwin erected a wooden hut for ‘The Douche’ near the well in his garden at Down. His daughter Etty recalled how she and Annie used to stand outside to ‘listen to the groans’ and an image of his coming out half-running and half frozen to take his usual walk in the Sand-Walk (Darwin’s thinking path), where they accompanied him (Keynes, 2001). A graphic description of ‘The Douche’ is provided by Joseph Leech in his account of the water cure in ‘Three Weeks in Wet Sheets’ (1856) from our Palfrey collection at LP 615.853. In Darwin’s letter to Fox in January, 1850 he explains ‘You ask after water cure.— I go honestly on & had the douche 36o to 37o for 5 minutes & the shallow bath with water at 39o for 4 minutes this very morning: it is sharp work, but not half so sharp as you would think & admirably invigorating.— My health is better than when you were here.’

‘The Douche’ in Leech’s Three Weeks in Wet Sheets (1856) from our Palfrey collection at LP 615.853

Just as things were improving for Darwin, tragedy struck. In October, 1850, Annie and Etty went to Ramsgate for a seaside holiday with their Governess Miss Thorley, joined two week’s later by Charles and Emma. Emma at the time noted Annie’s ‘bright face on meeting us at the station’. Etty spent time with her father on the beach and the children had collected shells of all kinds ‘piddocks, limpets, tellins and scallops’ with Charles later adding shells he had collected on the Beagle voyage that no-one desired to describe to their collection. Within a few days of Charles and Emma’s arrival, Annie developed a fever and headache. A fierce autumn storm led Charles, Etty and Miss Thorley to return home, with Emma following with Annie a few days later when well enough to travel. Annie became seriously ill in the months that followed. After a second visit to their physician Dr Henry Holland, Emma writes in her diary ‘Annie began bark’ (Keynes, 2001).

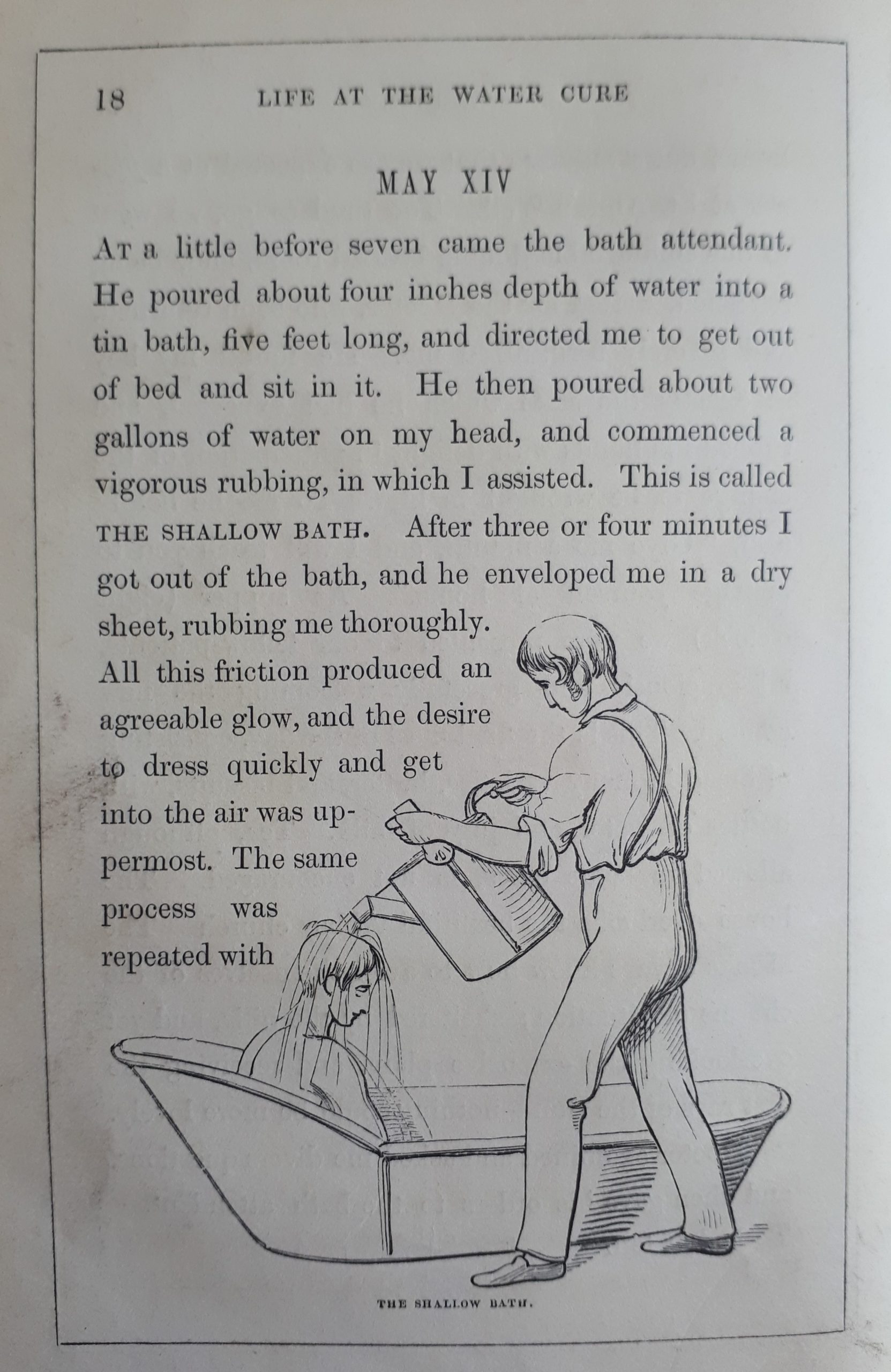

‘The Shallow Bath’ treatment as illustrated in R.J. Lane’s Life at The Water Cure 1846 at LP 615.853

With Dr. Holland unable to help Annie, arguably Darwin’s most beloved of his children, he turned to Dr. Gully who suggested she come to Malvern in the Spring for water treatment. Darwin was himself still taking ‘The Cure’ and was reporting his own progress daily. In March, 1851 Darwin writes to his cousin Fox ‘I have brought my eldest girl here & intend to leave her for a month under Dr. Gully; she inherits I fear with grief, my wretched digestion. I return in a day or two home.’ Amongst the treatments previously described, Annie was given the dripping sheet and spinal wash and every three to four days underwent ‘Packing’, once a week sweated by the lamp, and in a change of treatment for mid-February was given a shallow bath and footbath every morning (Keynes, 2001).

Darwin used his training as a naturalist to record Annie’s progress from ‘well very’ to ‘well almost very’, ‘well’, ‘well not quite’, ‘good’, ‘pretty good’ and ‘poorly a little’ to ‘poorly’. Darwin’s letters to Emma, such as the letter of 19th April, 1851 gave a detailed report of Annie’s health. The aim was simple, to find out what was affecting her and for Gully to find a pattern of treatment whilst keeping Emma informed daily who, now heavily pregnant with her son Horace, remained at Down House.

Daguerrotype of Annie Darwin taken in 1849

Despite their best efforts Annie succumbed to fever and died on the 23rd April, 1851. Darwin writes in his letter of the day:

My dear dearest Emma

I pray God Fanny’s note may have prepared you. She went to her final sleep most tranquilly, most sweetly at 12 oclock today. Our poor dear dear child has had a very short life but I trust happy, & God only knows what miseries might have been in store for her…God bless her. We must be more & more to each other my dear wife— Do what you can to bear up & think how invariably kind & tender you have been to her.— I am in bed not very well with my stomach. When I shall return I cannot yet say. My own poor dear dear wife.

- Darwin

The letters between Charles and Emma from the Darwin Correspondence Project here along with their Daughter Etty’s publication of letters demonstrate the depth of their relationship, the poignancy of events leading up to Annie’s death and their terrible sadness at her loss. Henrietta (Etty), writes that ‘It may almost be said that my mother never really recovered from this grief. She very rarely spoke of Annie, but when she did the sense of loss was always there unhealed. My father could not bear to reopen his sorrow, and he never, to my knowledge, spoke of her.’ (Litchfield, 1904). A week later, Darwin wrote a very moving memorial to her life here, at the end to which he writes:

‘We have lost the joy of the Household, and the solace of our old age:— she must have known how we loved her; oh that she could now know how deeply, how tenderly we do still & shall ever love her dear joyous face. Blessings on her’.

The Grave of Annie Darwin at Great Malvern Priory Churchyard © Anthony Roach

Annie was buried in Great Malvern Priory churchyard and Annie’s headstone can be seen at the Abbey church-yard at Malvern. It simply reads after her name ‘A dear and good child.’ Darwin did not attend the funeral, instead Emma’s aunt Fanny Allen attended on his behalf (at her suggestion), writing that ‘I know no other human being whom I could have asked to undertake so painful a task’.

Whilst Darwin’s health had improved as Fanny observed in a letter to her sister on 31st March 1851 writing ‘He is looking uncommonly well and stout, and certainly the water cure seems to have been effectual in his case. There is something uncommonly fresh and pleasant in him’ he never really recovered from his grief over the death of Annie. Keen to distract himself, Darwin returned to Down House and Volume 1 of his monograph on barnacles, all the while continuing his water treatment. After eight painstaking years, Darwin’s ‘Living Cirripidea’ was completed and you can find out more about the legacy and importance of Darwin’s barnacle specimens (many of which now reside at the Natural History Museum, London) from Curator Miranda Lowe in conjunction with the Linnean Society here. On 7th September 1854 he wrote to Hooker thanking him for requesting a copy saying

‘I have been frittering away my time for the last several weeks in a wearisome manner, partly idleness, & odds & ends, & sending ten-thousand Barnacles out of the house all over the world. But I shall now in a day or two begin to look over my old notes on species.’

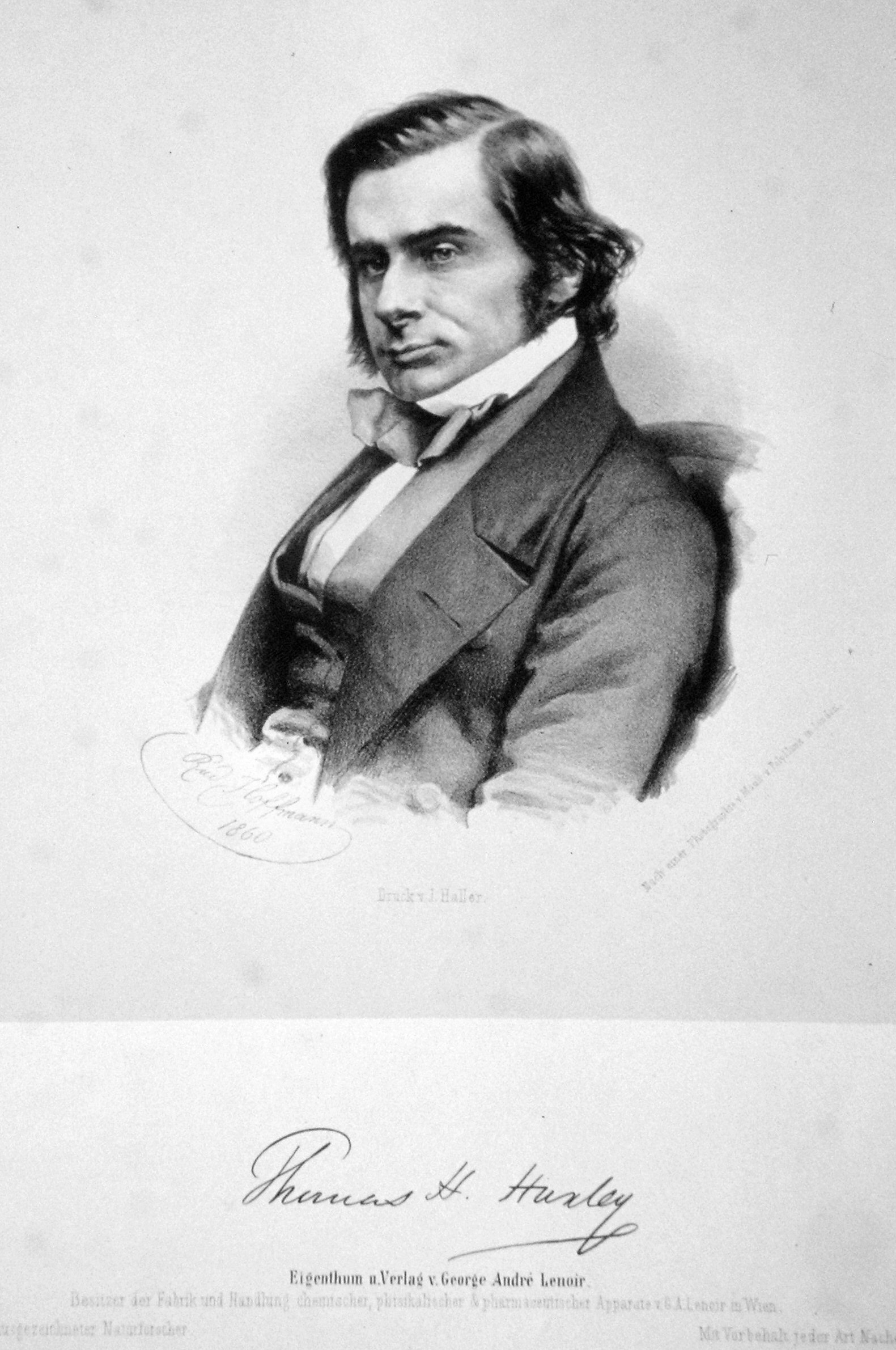

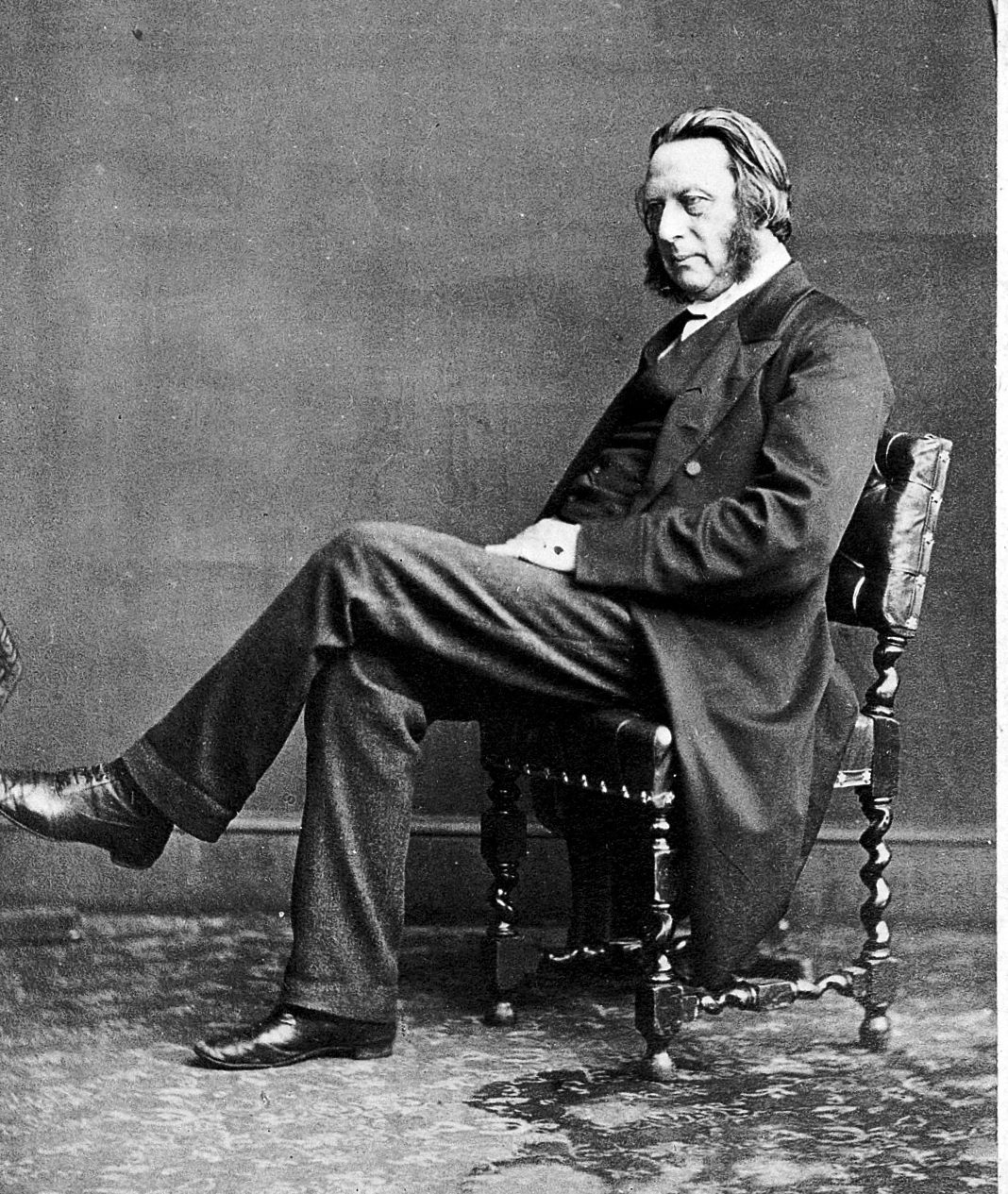

Thomas Henry Huxley, Lithograph by Rudolf Hoffmann (1860)

10 years had passed since Darwin had considered publishing his ‘Origins’ manuscript and the idea of the fixity of species came under considerable pressure during the barnacle years with 34 different scientists publishing on the species question since 1800. Darwin’s barnacle research was also well received by the Zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley stating ‘Mr Darwin’s present work shows him to be as able an observer of nature on the small as on the large scale’ (Stott, 2003). Huxley – a self-taught expert on vertebrates and Professor of Natural History of the Royal School of Mines would become Darwin’s most ardent supporter of ‘Origins’ and nicknamed ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’.

As Darwin began to review his notes, he had to provide evidence to a multitude of different problems and expected-criticisms of his theory, which alongside his worries about shaking the Christian foundations of society was perhaps another reason for delaying publication. For instance, if as Darwin theorised that life had evolved from common ancestor(s), how could species so similar to one another occur on completely different continents. This he addresses in a letter to Hooker on 8th July 1856 asking for plant species to cite cases that favour multiple creations. Darwin’s friends were keen that he publish, at least something and soon. Charles Lyell says as much in a letter on 1st May 1856 ‘I wish you would publish some small fragment of your data pigeons if you please & so out with the theory & let it take date—& be cited—& understood’.

It’s hard to be sure if Darwin’s health had improved sufficiently to write well. A letter to his cousin W.D. Fox nearly a year later gives a sense of Darwin’s continued affliction, ‘Nervous Dyspepsia’ or otherwise saying ‘I am well convinced that the only thing for Chronic cases is the water-cure.’ as he writes about taking the cure again, but this time at Moor Park, Surrey with Dr. Edward Wickstead Lane. He goes on saying ‘But I, also, think it highly probable that we all shall move to Malvern this summer, not for my sake, but for Etty’s, who has now been out of health for some six or 8 months’….‘I believe that I worked too hard at home on my species-Book, which progresses, but very slowly.’

Statue of Alfred Russell Wallace at the Natural History Museum, London © Anthony Roach

Out of the blue, Darwin then received a letter from a naturalist in Celebes, South East Asia, who he corresponded with previously for animal specimens. It was Alfred Russell Wallace, who, whilst in a malarial fever, had come to the same conclusions as Darwin on the origin of species. Darwin in his letter to Wallace of 1st May 1857 ‘This summer will make the 20th year (!) since I opened my first-note-book, on the question how & in what way do species & varieties differ from each other.— I am now preparing my work for publication, but I find the subject so very large, that though I have written many chapters, I do not suppose I shall go to press for two years.’ Darwin, gracious to the last in his letter to Charles Lyell says ‘There is nothing in Wallace’s sketch which is not written out much fuller in my sketch copied in 1844, & read by Hooker some dozen years ago’. He asks whether he can honourably publish his sketch now Wallace has come to the same conclusions saying ‘I would far rather burn my whole book than that he or any man shd. think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit.’

Whilst some feel Wallace was perhaps treated unfairly and you can read more about the whole story here, Wallace appears to have agreed graciously to the suggestion put forward by Hooker and Lyell who wrote to the Linnaean Society that they jointly publish an abstract of Darwin’s sketch alongside Wallace’s article on “The Laws which affect the Production of Varieties, Races, and Species”. This is shown by Wallace’s response to Hooker on 6th October, 1858 in Alfred Russell Wallace, Letters from the Malay Archipelago as he writes ‘I must thank you again for the course you have adopted, which while strictly just to both parties, is so favourable to myself’ (Van Wyhe & Rookmaaker, 2013, p181).

A well-thumbed sixth edition of Darwin’s The Origin of Species available at Ref 575.0162 DAR

As Darwin had been pondering the question for 20 years, Lyell felt Darwin should have prominence. A reading of the two papers occurred at a meeting of The Linnean Society on 1st July 1858 with little, if any impact on its audience at all. Wallace’s annotated copy of the paper is shown here. On November 24th 1859, Darwin finally published ‘The Origin of Species’ and it sold out immediately. A sixth edition of the book is available at The Hive at Ref: 575.0162 DAR. Whilst some argue that Darwin had hastily published, whilst his hand had been forced, he was anything but hasty as Rebecca Stott in ‘Darwin and The Barnacle’ points out in Darwin’s preface to his book as he writes:

‘After five years’ work, I allowed myself to speculate on the subject, and drew up some short notes; these I enlarged in 1844 into a sketch of the conclusions, which then seemed to be probable: from that period to the present day I have steadily pursued the same object’.

Unsurprisingly, Darwin’s book received criticism from contemporaries including the Bishop of Oxford Sam Wilberforce (who would famously argue with Huxley in the Oxford Great Debate of 1860) and Richard Owen, Superintendent of the British Museum (Natural History), later The Natural History Museum, London who refused to believe species could change over time without divine intervention. However interest in society at large to debate the origins of life and subsequently through Darwin’s later work The Descent of Man where he explored the evolution of humans, Darwin’s theory gained support in the years that followed.

The Natural History Museum, London conceived by Richard Owen as a cathedral to the natural world with the aim of explaining the divine order of nature to its visitors © Anthony Roach

Despite facing down many obstacles to publish his theory, Darwin continued to struggle with illness and in a letter written to his cousin W.D. Fox on 16th March, 1863, he writes solemnly

‘I suppose we must go to Malvern; but it breaks my heart’

Darwin’s sadness over Annie is evident in his reply as he refers to Dr. Gully’s establishment in Great Malvern. However, Gully himself was seriously ill and unable to practise at the time and instead was treated at the hydropathic establishment of James Smith Ayerst (who in conjunction with Gully had set-up at Old Well House, Malvern Wells), though it was publicised in Ayerst’s name. Gully eventually gave up his own practise in the late 1850’s.

William Darwin Fox, second cousin of Charles Darwin © Wellcome Trust (CC BY 4.0)

Darwin instead visited with his son Horace for treatment and the family stayed until the 12th or 13th October, 1863. Indeed, in a previous letter to Fox just five years after Annie died, his grief at Annie’s loss was very strong as he writes ‘Thank you for telling me about our poor dear child’s grave. The thought of that time is yet most painful to me’.

In his letter to his cousin Fox on the 4th September, he asks the whereabouts of Annie’s headstone on behalf of his wife Emma and also explains his treatment under Ayerst writing:

‘I have had a bad amount of sickness of late & came here yesterday; & as I could get no country in Grt. Malvern we are here & I have put myself under Dr. Ayrehurst, though very sorry not to be under Dr. Gully. Emma came here a day or two first & took this house.’ ‘And now I come to the painful subject which makes me write at once. Emma went yesterday to the church-yard & found the gravestone of our poor child Anne gone…Now some years ago, you with your usual kindness visited the grave & sent us an account. Can you tell what year this was?’

It appears that Darwin, despite confirming the location for Emma, never did visit Annie’s grave himself. Following his treatment at Malvern Wells Emma writes in her letter to W.D. Fox of December, 1863 ‘I can give rather a better account of Charles this week but he is never long without attacks of sickness. The water cure seemed to do him harm & Dr Gully quite owned that he was not strong enough to bear it’. Was it Darwin’s grief over the death of Annie returning that subsequently led to a decline in his illness? Emma writes of her husband in her letter to Fox on 6th May, 1864.

‘I must tell you how ill Charles has been since we were at Malvern. He has had almost daily vomiting for 6 months & it was becoming a great anxiety that it should be stopped. About 3 weeks ago Dr Jenner saw him for the 2nd time & he has succeeded in stopping the vomiting & he has been 3 weeks free from it, but I am afraid of the least exertion bringing it on till his stomach has more recovered its strength.’

The Well House, Malvern Wells where Darwin came for treatment at Dr. Ayerst’s hydropathic establishment, Rock & Co. London, 1862

The film Creation (based on Randal Keyne’s book ‘Annie’s Box’) released during Darwin’s bicentenary year portrays the psychology of Darwin, his life and struggles. It focuses (some, may argue too much) on the close relationship with his wife Emma and his anxieties over his theory and not on his other scientific achievements. However, it does accurately portray Darwin’s struggle with illness, his visit to Malvern and a moving portrait of his attempt to save Annie’s life in Malvern through the water cure with Dr. Gully (though a moving exchange between Gully and Darwin on his return to Malvern after Annie’s death never happened in reality). We will never know what the chief cause of Darwin’s illness was, but historian John Van Whye writes that the death of Annie was arguably the most distressing event in Darwin’s life (Van Whye, 2007, Darwin Online).

Poster of the film ‘Creation’ released in 2009 which charted the life and work of Charles Darwin, played by Paul Bettany and based on Randal Keyne’s book ‘Annie’s Box’

Steve Thompson writes in ‘The Great Naturalists’ ‘It is possible that he contracted some tropical disease (Chaga’s disease is a favourite candidate), but the correspondence between ill health and mental pressure is striking’ (Huxley, 2007). Meanwhile Steve Jones in ‘Darwin’s Island’ writes ‘The cause of his illness was not known: a conflict between Christian belief and rationalism, a parasite picked up in Brazil..’ He goes on to say Darwin alone wasn’t a sufferer of the so-called ‘Demon of Dyspesia’. It afflicted many others including Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, George Eliot and Florence Nightingale leading to several pharmaceutical ventures and The Wellcome Trust which ironically paid for the sequencing of DNA (Jones, 2009).

Charles Darwin’s statue on the steps of the Natural History Museum, London © Anthony Roach

It is clear Darwin continued to struggle with illness, even after his theory was published, despite this, he continued to undertake experiments and gather evidence across the spectrum of natural sciences at his ‘living laboratory’ at Down House, Kent. Darwin’s observations, analysis and subsequent publications across disparate subjects from ‘Insectivorous Plants’ (1875) to the ‘Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms’ (1880) demonstrates he was ‘The Complete Naturalist’ (Huxley, 2007). Today many of Darwin’s specimens are on display at the Natural History Museum, London and Darwin’s statue was moved in 2009 to the central steps in honour of his achievements.

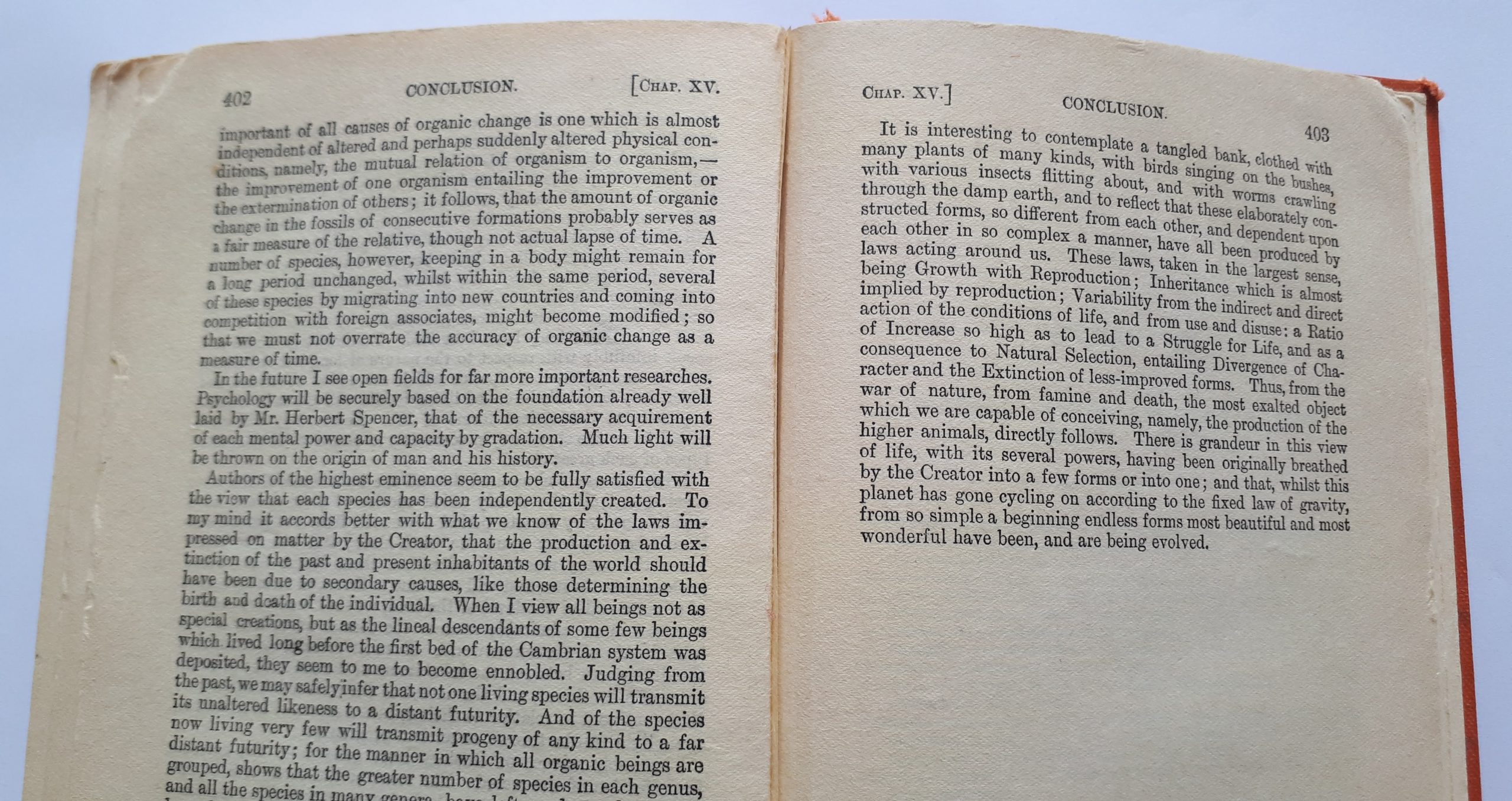

Final page of The Origin of Species where Darwin writes the now infamous words ‘endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been and are being, evolved’ available at Ref 575.0162 DAR

From the domestication of pigeons, to discussion of the structure and variation of species, their organs and their biogeography, the fossil record and its imperfection and of the vastness of geological time, Darwin’s ‘Origins’ gave us a glimpse into a vast story stretching back millions of years with all species connected in one vast ‘Tree of Life’ by common ancestors. This has now been proven by modern genetics and DNA sequencing. Naturalist Sir David Attenborough in Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life (Attenborough, 2009) summarised Darwin’s legacy saying

‘above all, Darwin has shown us, that we are not apart from the natural world, we do not have dominion over it, we are subject to its laws and processes, as are all other animals on Earth, to which indeed, we are related’.

Anthony Roach F.L.S.

Read the earlier articles:

Darwin & The Water Cure – Part 1 Mr. Darwin & Dr. James Manby Gully

Darwin and The Water Cure – Part 2 Darwin, Malvern & Barnacles

Further Information:

The Darwin Correspondence Project

The Water Cure in Chronic Disease

Author: James Manby Gully. 1851. – Available at Level 2: Local Lending – L 615.853

Life at the water cure : or a month at Malvern : a diary to which is added the sequel.

Author: Lane, R. J. 1846 Available at Level 2: Palfrey Collection – 615.853

Three Weeks in Wet Sheets

Author: Joseph Leech. 1856. – Available at Level 2: Palfrey Collection – 615.853

Annie’s box: Charles Darwin, his daughter and human evolution

Author: Keynes, Randal. 2001. – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference – B DARWIN,C

Alfred Russel Wallace : letters from the Malay archipelago

Author: Wallace, Alfred Russel, 1823-1913,

Edited by Van Wyhe, John, 1971-Rookmaaker, L. C. 2013. – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference – 508.092 WAL

Darwin and The Barnacle

Author: Stott, Rebecca. 2003 – Available at Malvern Library, Local Reference

Darwin’s island : the Galapagos in the Garden of England

Author: Jones, Steve 2009. – Available at Level 3: Main Collection – 576.82 JON

The Great Naturalists

Author: Huxley, Robert, 2007. – Available at Level 3: Main Collection- 570.922

Post a Comment