The Bromsgrovian botanist who earnt His ‘Majesty’s admiration’

- 12th March 2021

A discovery in our archive reveals how a local scientist contributed not only to popularising horticulture in the 19th century but significantly during his life to the people and town of Bromsgrove. In fact, held in such high esteem, he later earnt his ‘Majesty’s admiration’ from the King of Prussia.

A selection of ‘Library Pamphlets’

Whilst having to adapt delivery of our service during the Lockdowns it has given us an opportunity to use the time to undertake projects at home, such as cataloguing, research, promoting our service on social media and working with my team on specific projects. One of the collections I’m currently working on is creating an accurate list of a diverse range of original and copies of programmes, journal articles, diaries, newspaper articles, archaeological reports and other pamphlets which came from Worcestershire History Centre before the service moved to The Hive in 2012.

These were items which the then Local Studies Librarian felt should be catalogued as archives, rather than stored on open shelves as books. However, there was no kind of list as she removed them, so we have no idea what the boxes contain and whether we already have them in our collections somewhere or not. If we already have them, we may not wish to keep them as maintaining storage for future collections is just as important, alongside taking stock of what we already have.

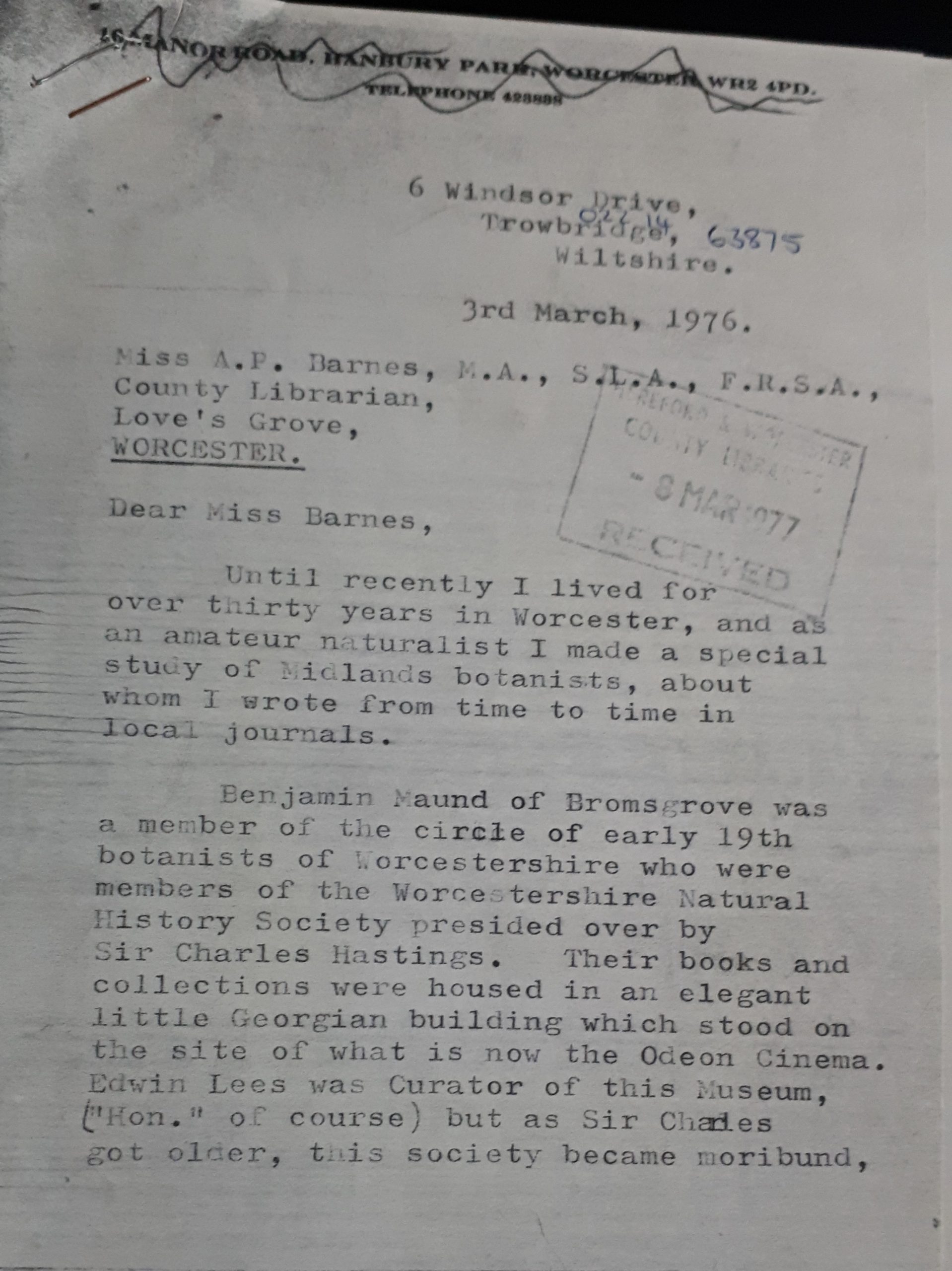

First page of the letter of Mrs Mary Jones to the County Librarian dated 3rd March 1976

Alongside my passion for wildlife I have a particular interest in the history of Natural History and having reached Box 21 (of 55 boxes!), the discovery of a letter by a Mrs. Mary Jones to the County Librarian dated 3rd March 1976 requesting a display to celebrate a local botanist piqued my interest. Benjamin Maund, a ‘son of Bromsgrove’ she argued was not well-known or honoured in Bromsgrove. In her letter she explains Maund was part of a group of local naturalists who were members of the Worcestershire Natural History Society founded in 1833 by Hon. Curator Edwin Lees, which later became the Worcestershire Naturalists’ Club whose Transactions of the field meetings, I had explored in our Reference collection on Level 2.

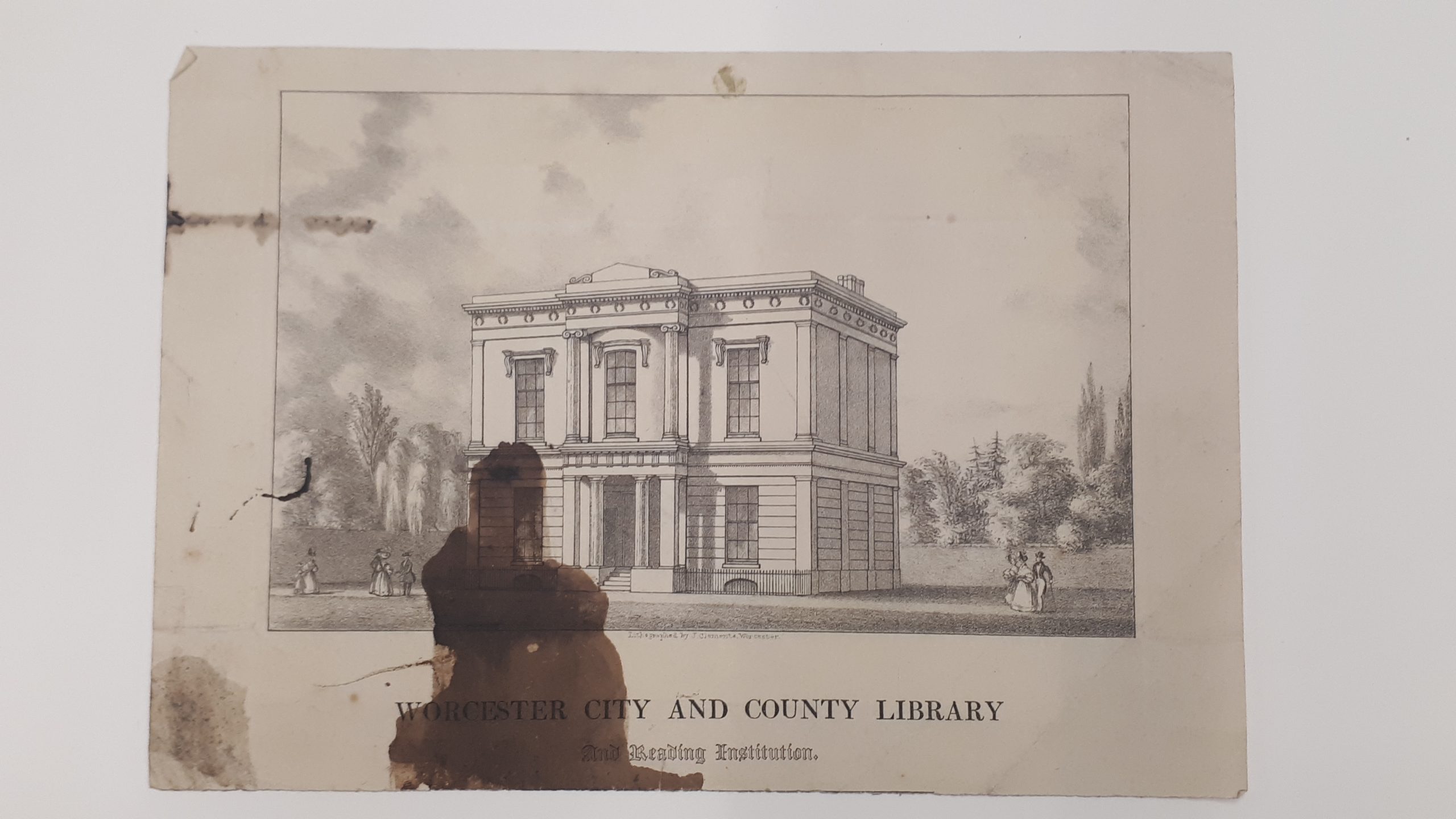

Lithograph of Worcester City Library & home of Worcestershire Literary & Scientific Institute founded on 12th January 1829 held at Ref b 899:1584 BA14868 (i) 7

Mary noted that ‘their books and collections were housed in an elegant little Georgian building which stood on the site of what is now the Odeon cinema’ in Foregate Street. I wanted to see if I could establish these events using our archives and after some digging I was delighted to find a lithograph of the building at Ref BA1484 (i) 7 described as the City and County Library held with the Minute book of the Worcester Literary and Scientific Institute founded by Lees who was joint Secretary.

The contribution of Benjamin Maund who would make his home for nearly 50 years in the town of Bromsgrove had largely been forgotten from history until a plaque was unveiled in 1928 by Bromsgrovians keen that his legacy should be honoured in the local Parish church. We will explore Maund’s life and work through documents held at WAAS, books and other sources including particular events in Maund’s personal life.

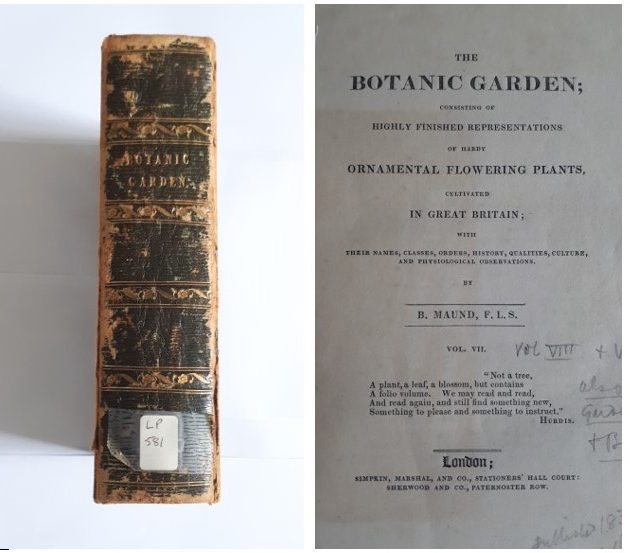

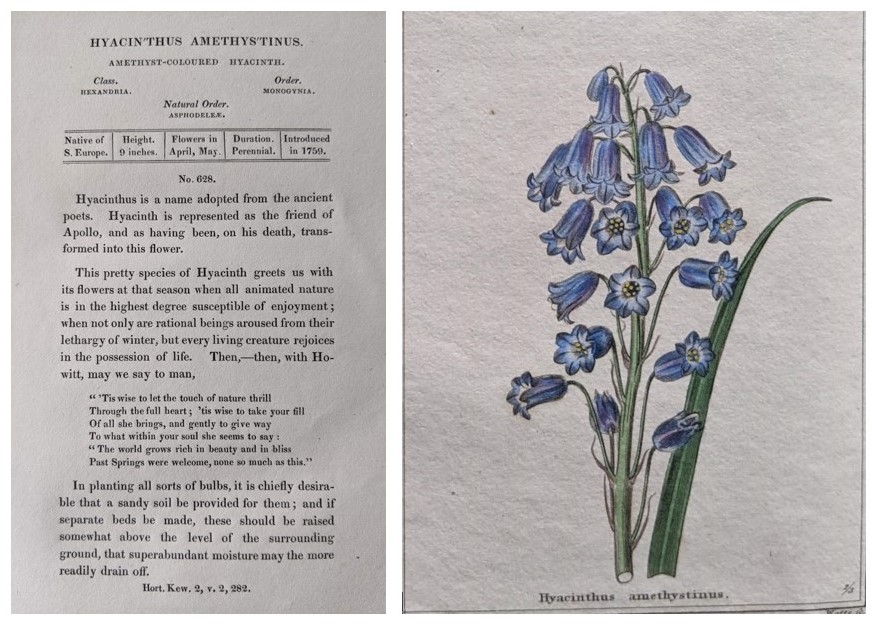

Spine & Title page of Volume VII of Maund’s The Botanic Garden at Ref LP 581

By 1832 and already a fellow of The Linnean Society of London, the most distinguished natural history society of the day, Benjamin Maund had written, printed and published four volumes of The Botanic Garden from his own press at Bromsgrove in Worcestershire. Volume VII of which is held within our Palfrey collection at LP 581. His aim in producing The Botanic Garden was a work that everyone could afford and information that would be both useful and interesting (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998). A good example of this is in his description of Amethyst-coloured Hyacinth Hyacinthus amethystinus, a bluebell native to the Eastern Mediterranean that is similar to the non-native Spanish bluebell H. hispanica that freely interbreeds with the native common bluebell H. non-scripta. Besides his literary or cultural references Maund includes most, if not all, of the information that you would find today in modern plant reference books such as flowering period, size, plant type and soil conditions for planting. Monty Don himself I’m sure would be very impressed by Maund’s books that blend literary references, illustrations with practical horticultural advice.

Description of and plate of Hyacinthus amethystinus from Maund’s The Botanic Garden Vol VII, p. 3 at Ref LP 581

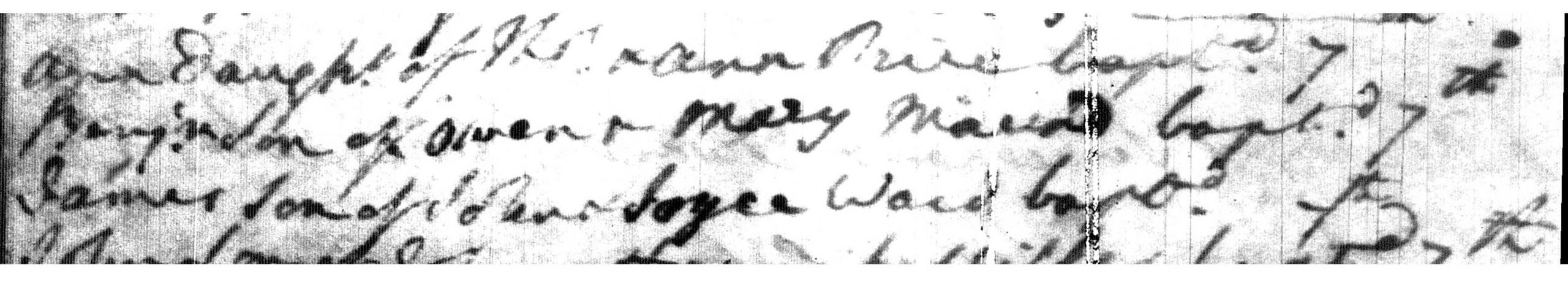

Maund, like many, had a modest start to life, baptised in 1790 to Mary and Owen who according to Margaret Cooper in an account of Maund’s career ‘farmed just inside the small town of Tenbury on Worcestershire’s western edge, an area for centuries famous for its fruit and hops.’ (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

Baptism entry

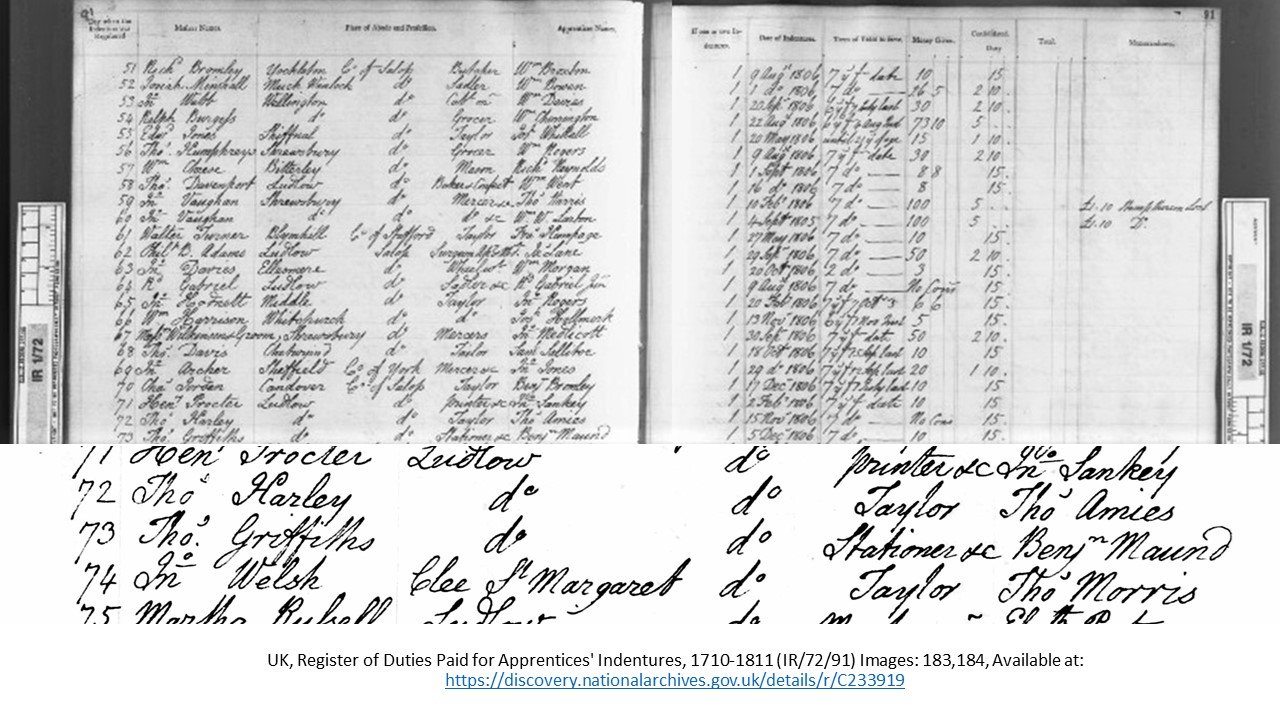

A surviving record of Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices’ held by The National Archives and also searchable via Ancestry shows that he was apprenticed to Stationer Thomas Griffiths with stamp duty recorded as being paid on 5th December 1806 under Ref: IR 1 /72/91. Griffiths wasn’t the leading bookseller of his day, however, after only 7 years, Maund was now a stationer himself and master of his own destiny (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

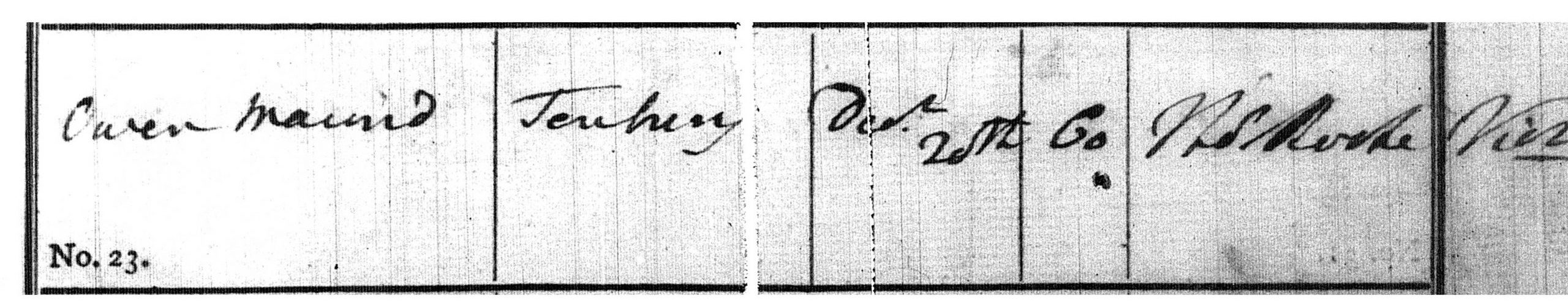

Burial entry of Owen Maund, Tenbury Wells (St. Mary), 25th December 1813

Having move to Bromsgrove, Maund had taken over the lease from the late Joseph Thompson, former printer, stationer and bookseller on Christmas Day 1813 (the same day his father was buried, as shown by his burial entry, who died without making a will). The agreement had been made with Thompson’s widow Sarah for ‘the Household Furniture, Types, utensils, in Trade and Stock in Trade…Good Will…Dwelling houses, Shops and Warehouses’ (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

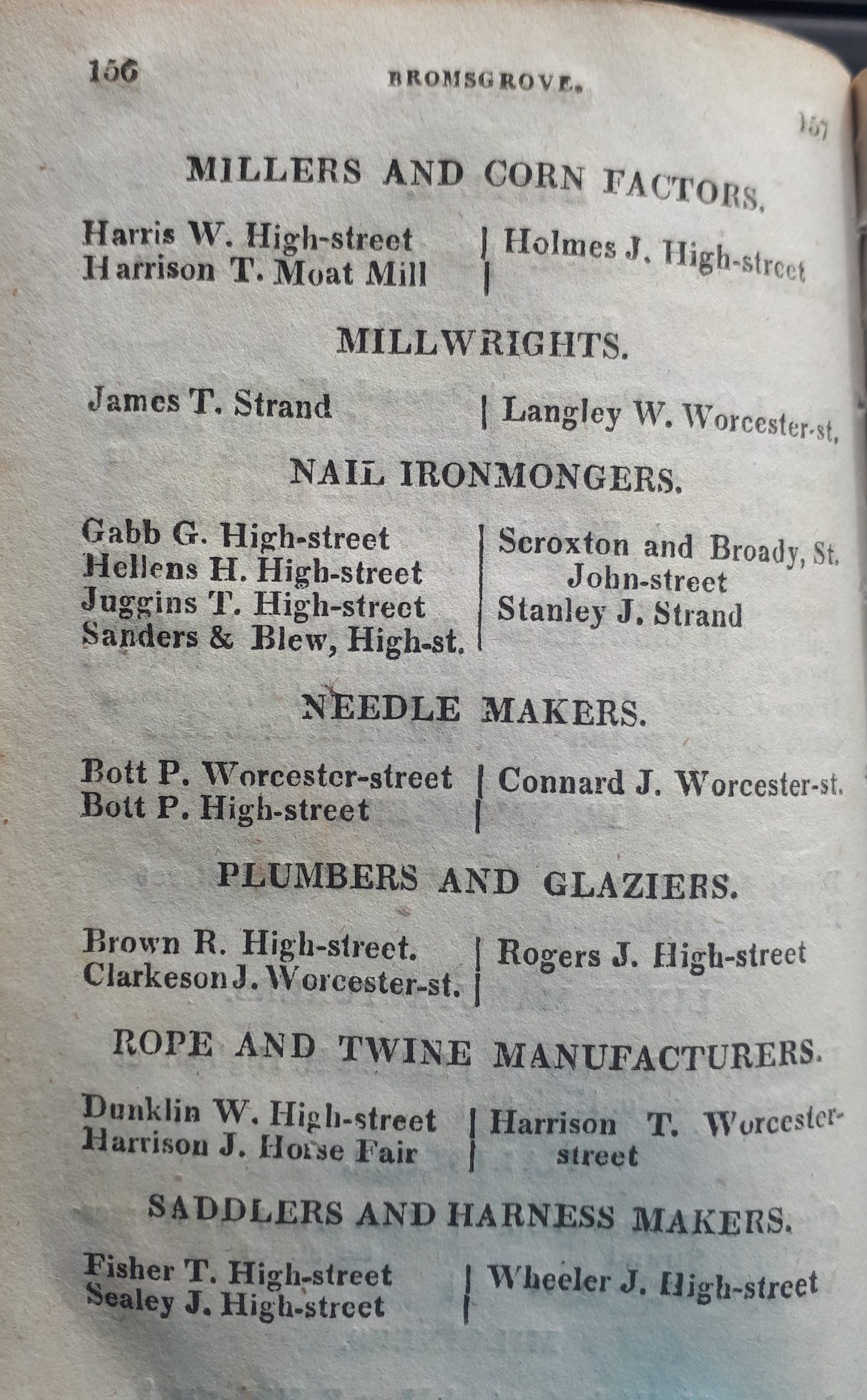

Examples of Bromsgrove Trades in Lewis, S. Worcestershire General & Commercial Directory, 1820

According to the Worcestershire General & Commercial Directory in 1820, Bromsgrove ‘contains one long street, in which are a considerable number of well-built houses’ and where ‘the principal manufacture consists in sheeting, table cloths and coarse linen; likewise in needles, nails, and other small articles in the iron trade, which gives employment to nearly one half of the population’. Bromsgrove was ideally situated half-way between Worcester and Birmingham, with a newly paved main street, with some fine houses, an ancient grammar school and an attractive hinterland (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

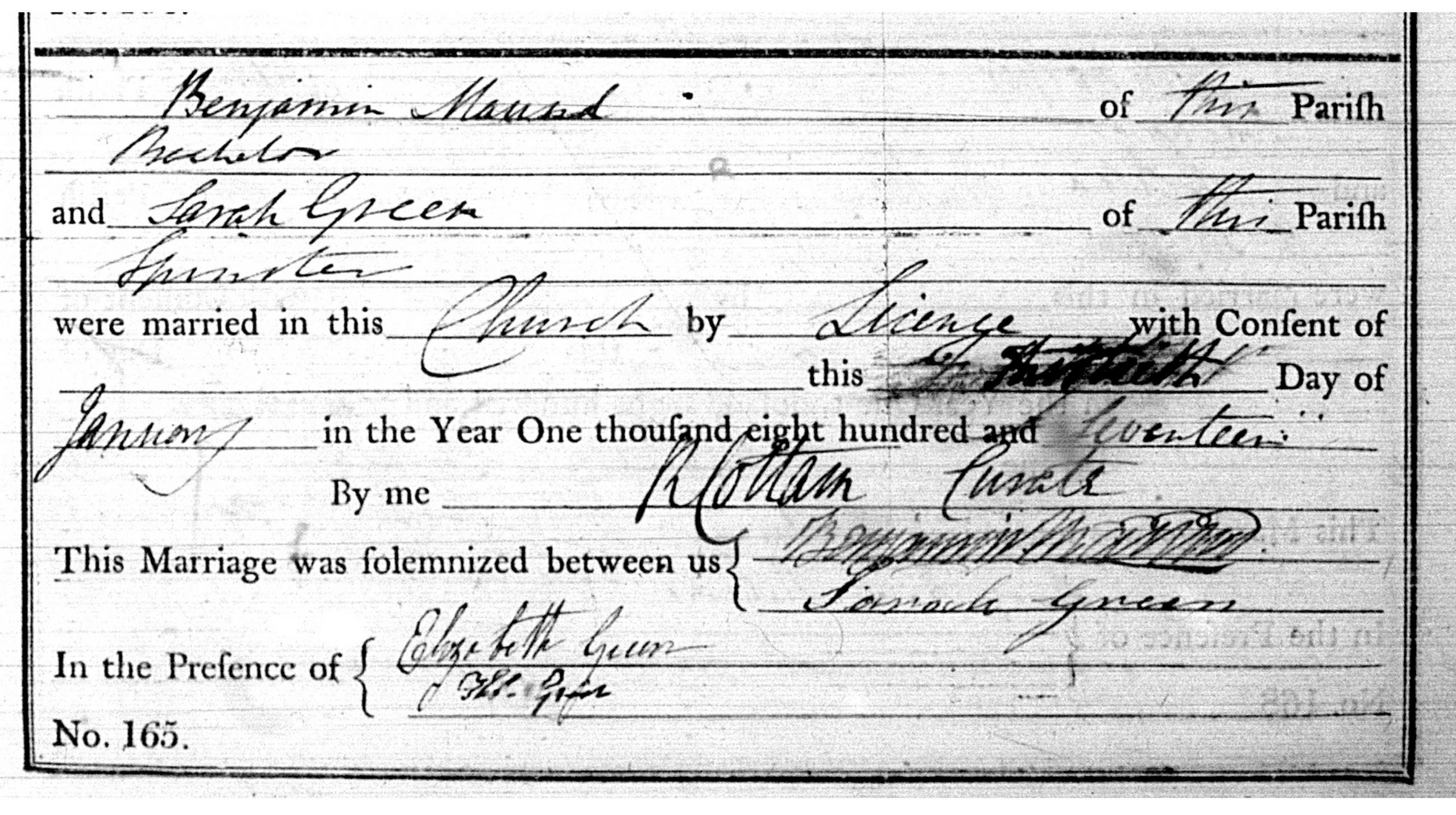

Marriage entry of Benjamin Maund, to Sarah Green, Bromsgrove St. John 13th January, 1817

Benjamin is later recorded in the Parish registers at St. John The Baptist, Bromsgrove marrying his wife Sarah (nee Green) on 13th January 1817. A year later, after establishing his business in the Market Place, he moved next door to the Crown Inn on High Street, the town’s busiest coach station and where Maund’s successor Alfred Palmer who would begin printing The Messenger (available on Microfilm at WAAS). The ground to the rear of his shop then offered the chance to develop his botanic garden (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

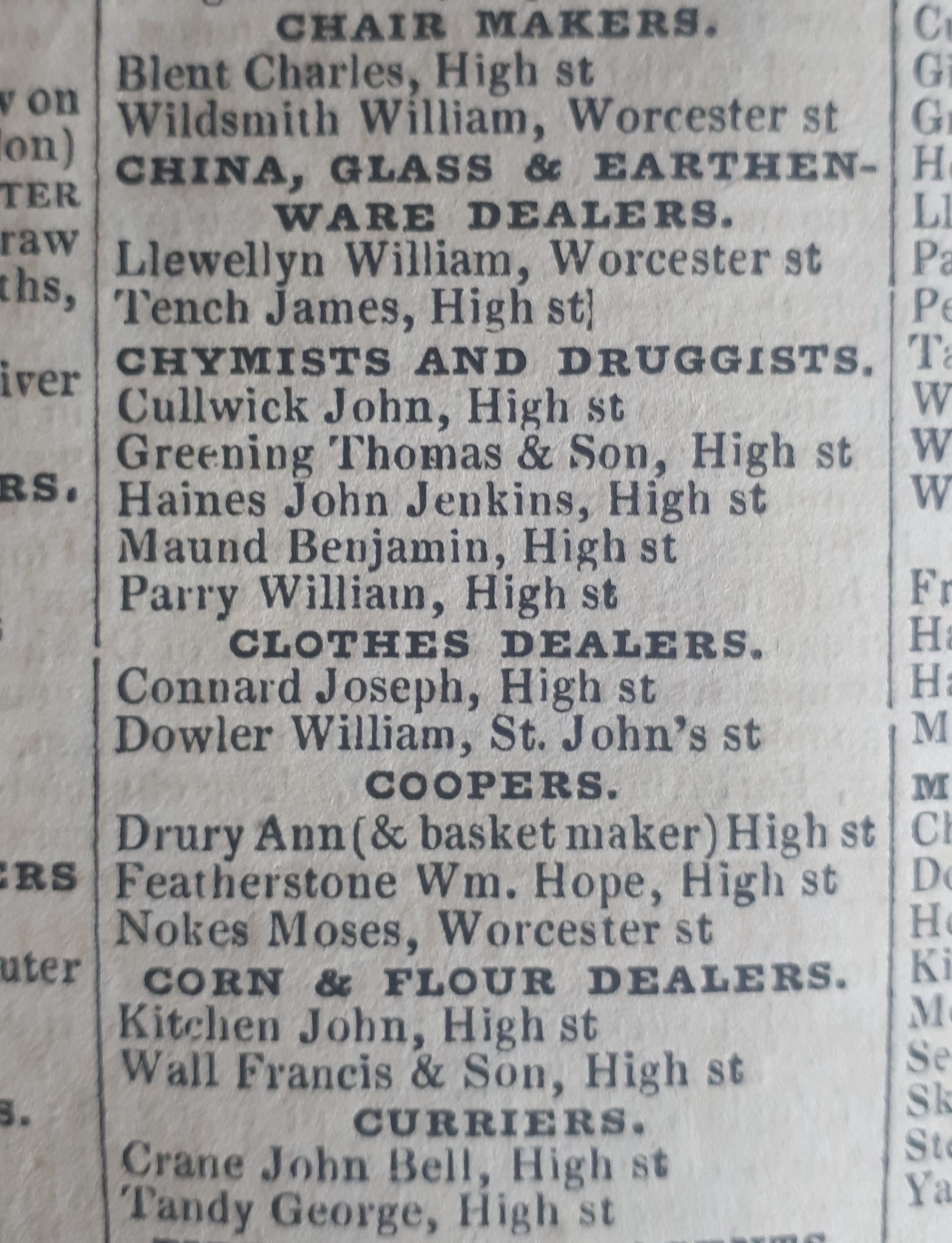

Evidence of Maund as a Chymist & Druggist in Piggot & Co. Commercial Directory, 1835

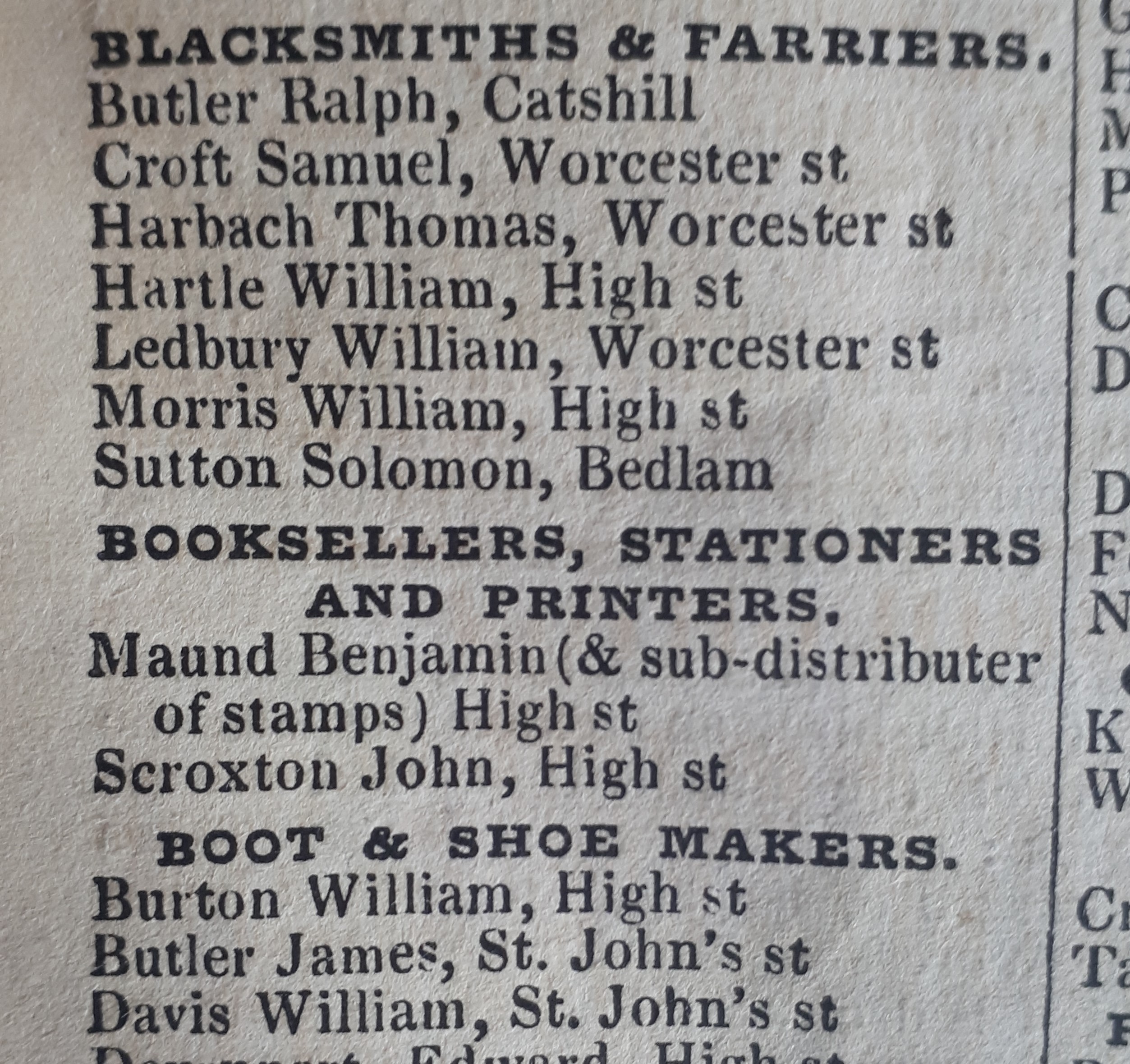

From records of Maund’s activities that do survive he seems to have had a natural flair for business as well as looking for new opportunities, whilst pursuing his passion for plants. A search of our Trade directories at The Hive illustrates this well. At the start of his career in 1820 he is listed as ‘Printer & Bookseller, High-St.’ in Lewis’ Worcestershire General & Commercial Directory. In 1835 he is listed as a ‘Chymist and Druggist’ in Piggot & Co. Commercial Directory and later took advantage of the new-fangled stamp described as ‘Bookseller, Stationer and Printer (& sub-distributer of Stamps) High-st.’ in Slater’s Directory of 1850.

Mention of Maund’s business in Slater’s Directory, 1850

Moore’s Almanack of 1842 reveals a lot about what was sold in his store. A good range of stationery as well as drawing materials, sheet music, musical instruments, penknives and brushes (hair, tooth and nail) as well as cordials, household cleaning agents, and personal hygiene items such as toothpaste, hair oil and shaving soap. It was the list of over 150 patent stock medicines that Maund specialised in, including those for sheep, cattle, horses and domestic pets such as his ‘universally approved sheep dip’ that demonstrate his scientific and entrepreneurial skills. Having been the son of a farming family he was interested in agricultural matters and is reported to have read widely on scientific matters, conducting all manner of practical experiments (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

It didn’t always go Maund’s way though and whilst undertaking printing for the Mechanics Institute, a mix-up with a parcel addressed to Mechanics Institute ended up at the Scientific and Literary Institute in error and may have cost him the business. John Scroxton who also was a printer on the High Street (as shown in our directories) stepped in (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

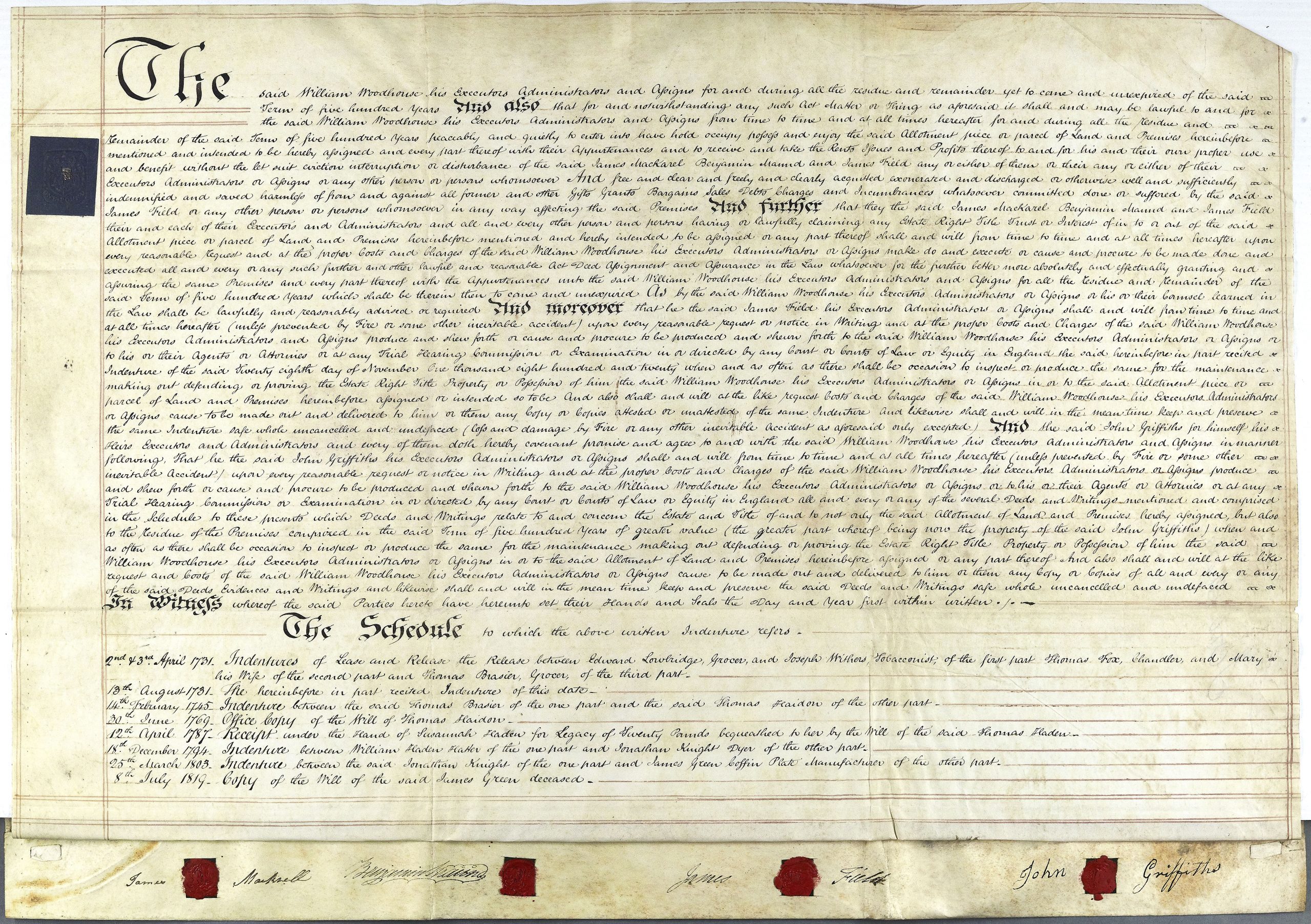

Assignment of an allotment of land at Sidemoor at Ref 705:1548 BA13566(2)

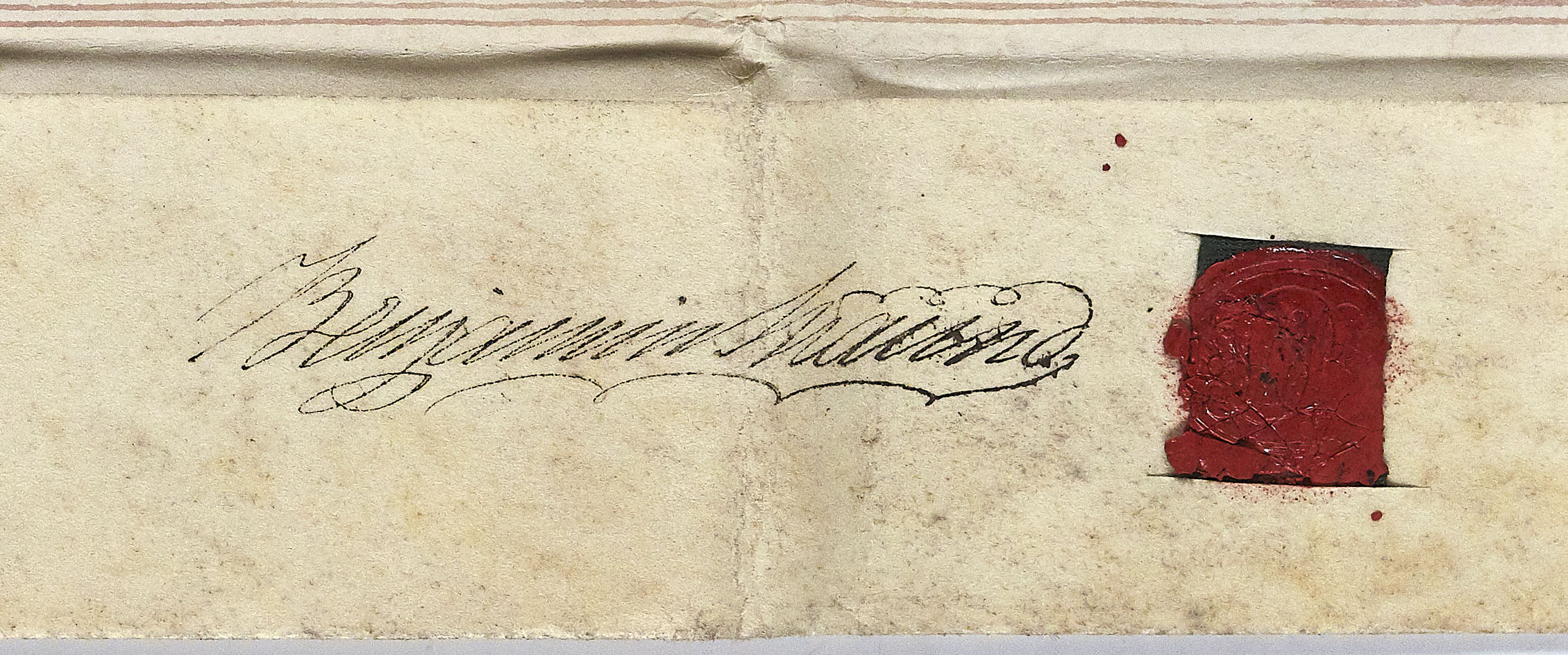

An exciting discovery adds further evidence that Maund was interested in progress, in new business ventures and in working with the people and town of Bromsgrove. An agreement in our archive at Ref: 705:1548 BA13566(2) illustrates this as Maund paid for an allotment of land at Sidemoor for the remainder of a term of 500 years between him, James Mackrel of Chaddesley Corbett, gentleman, James Field of the Chapelry of Elmbridge, gentleman and William Woodhouse of Bromsgrove for the princely sum of Sixty Pounds. Incredibly, his signature, along with the others is shown on the document and it matches perfectly with that of his Marriage entry of 1817.

Signature of Benjamin Maund at Ref 705.1548 BA13566

It is not fully clear what the land might have been used for, but two things are highlighted in the document which are of interest. The first relates to the land itself which is described as follows:

‘All that messuage (a dwelling house with outbuildings and land assigned to its use) or tenement situate lying and being at or near Sidemoor common in the Parish of Bromsgrove…’ and ‘All Buildings Barns Stables Gardens and Backsides thereto belonging together with all closed arable land, meadows and pasture ground and other appurtenances (an accessory or other item)’.

Secondly is the mention of ‘between Elizabeth Green Spinster of the first part’ suggesting a connection with Maund. Later the document explains her marriage to James Field saying ‘the then intended marriage between her and the said James Field.’ Could this be a relative of his wife Sarah Maund (nee Green) or is this just a coincidence? It turns out remarkably that Elizabeth Green is shown as a witness on Maund’s Marriage entry in 1817, thus suggesting that Elizabeth was Maund’s sister-in-law.

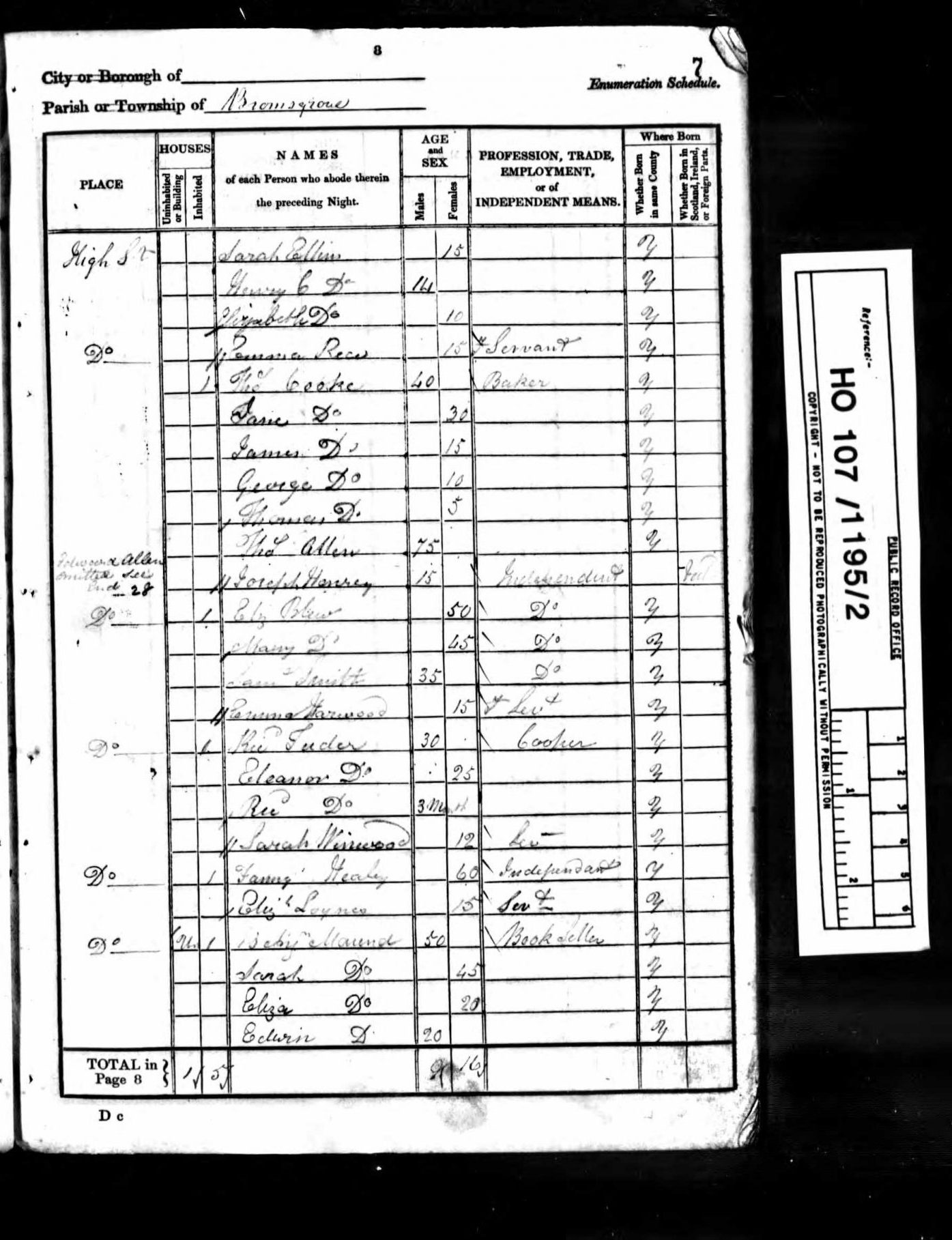

Benjamin Maund and his family (bottom) on the 1841 Census (copyright The National Archives)

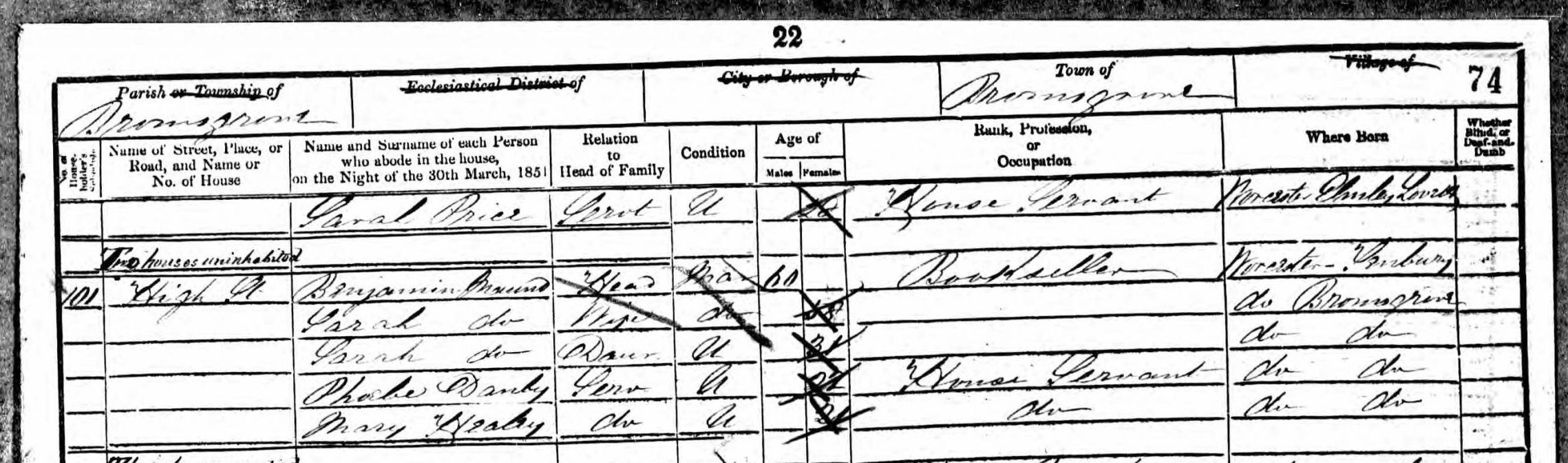

Whilst we cannot confirm what Maund and his family may have used the land for, we can infer from his business, knowledge of plants and medicines that he used some of this land or that at least the rear of his business to further his interest in plant varieties and horticultural practices. As Benjamin’s business flourished, so did his family and Census records give us some insight into Maund’s family life. By 1841, Benjamin who is 50 at this time, is listed as a Bookseller with his wife Sarah (45) and his five children, Eliza (Maund’s daughter Eliza may have been named in honour of Elizabeth, his sister-in-law) Sarah and Edwin (20), Jon (15) and Henry (10) along with Jon Lomoldey, Assistant and servants Mary Gundy and Hannah Steadman. By 1851 however there have been changes, with the other children having left home or married with only Sarah listed, along with her mother and father at 101, High Street.

Benjamin Maund and his family on the 1851 Census (copyright The National Archives)

Maund’s The Botanic Garden series was first issued in 1825 and running to 13 volumes depicted with great detail and delicacy ornamental flowering plants cultivated in the Royal Gardens (and was dedicated to the young Queen Victoria). Mary Jones in her research explained that Maund is reported to have first come to the attention of the Worcestershire Natural History Society at a report of the Society in 1835 where the then President, Sir Charles Hastings M.D. who would later become founder of the British Medical Association stated that ‘Mr Maund, with his usual taste and skill, has been cultivating and improving his botanic garden at Bromsgrove.’

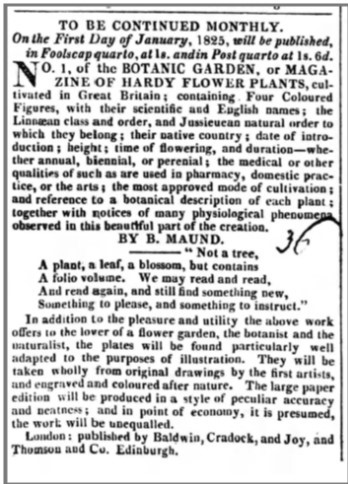

Advert for The Botanic Garden in the Berrows Worcester Journal on 25 Nov 1824

This is confirmed by Margaret Cooper in The Reach of Print that Benjamin spent a lot of his time in his garden at Crown Close, an open area to the rear of his premises where he carried out numerous experiments. He acquired seeds and plants from individuals, societies, botanic gardens and nurserymen and even complete strangers such as receiving Peroffski’s Erysimum in 1838 – just introduced in England – from St. Petersburg by ‘BPG’ who had seen it flowering in the imperial garden (BG Vol 8, 711 in Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

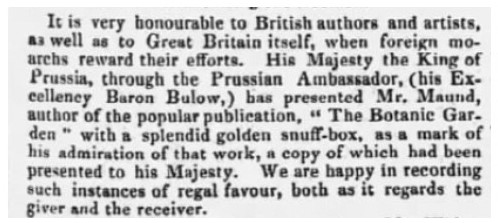

Reference to Maund being given a Golden Snuff-Box by the King of Prussia in The Bury and Norwich Post, 1834-03-12

Issued as a supplement to The Botanic Garden were 70 numbered prints under the title of The Fruitist. Each of these was a hand-coloured engraving and description of a particular fruit. The periodical attracted favourable comment from the outset and when Maund came to produce The Botanist in 1837 a botanical journal, the goal of which was to educate gardeners (which included five volumes of lavish hand-coloured illustrations) he was able to enlist the support from some of the most distinguished botanists of the day including Rev. John Steven Henslow, Professor of Botany at Cambridge who had recently published The Principles of Descriptive and Physiological Botany (1835) (famously Charles Darwin’s mentor and friend who recommended him as ship’s naturalist on H.M.S. Beagle). This was an exciting time for natural history when nurserymen, explorers and artists such as Marianne North and patrons of natural history such as Joseph Banks were encouraging naturalists to undertake expeditions all over the world to describe and gather new plants.

Maund’s collaboration with Henslow would cement his reputation. A man whose wide-ranging knowledge of plants and their physiology, interest in ornamental plant varieties and desire to popularise interest in horticulture and botanical illustration would lead to admiration and considerable notoriety in botanical circles and beyond. Cooper writes that Maund’s writing ‘reveals a natural educator, a man keen to convey his enthusiasm in as readable a manner as possible’ (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998). Examination of Maund’s legacy by James Britten at the beginning of the 20th century wrote of Maund that the text of ‘The Botanist’ achieved ‘a level unattained by any other magazine’ (Britten, J., Journal of Botany, 56 (1918) 241). However, credit for some of Maund’s success is owed to ‘The Misses Maund’- the daughters Eliza and Sarah whose lives remain largely undocumented as reported by Cornell University and other botanical artists such as Augusta Innes Withers.

Gladiolus floribundus on Plate 2 of Vol VII of Maund’s The Botanic Garden painted by Miss S. (Sarah) Maund & Nemophila insignis on Plate 3 of Vol VII of Maund’s The Botanic Garden painted by Miss (possibly Eliza?) Maund at Ref LP 581

Mary Jones reported that an old Bromsgrovian who remembered the Maund family said ‘that he understood that the hand-coloured plates were painted by Mr. Maund’s sister and daughters at a house in Church St., Bromsgrove’. Whilst I cannot confirm Mr Maund’s sister’s involvement, evidence of both Sarah and Eliza’s involvement is documented on the individual plates, as shown above.

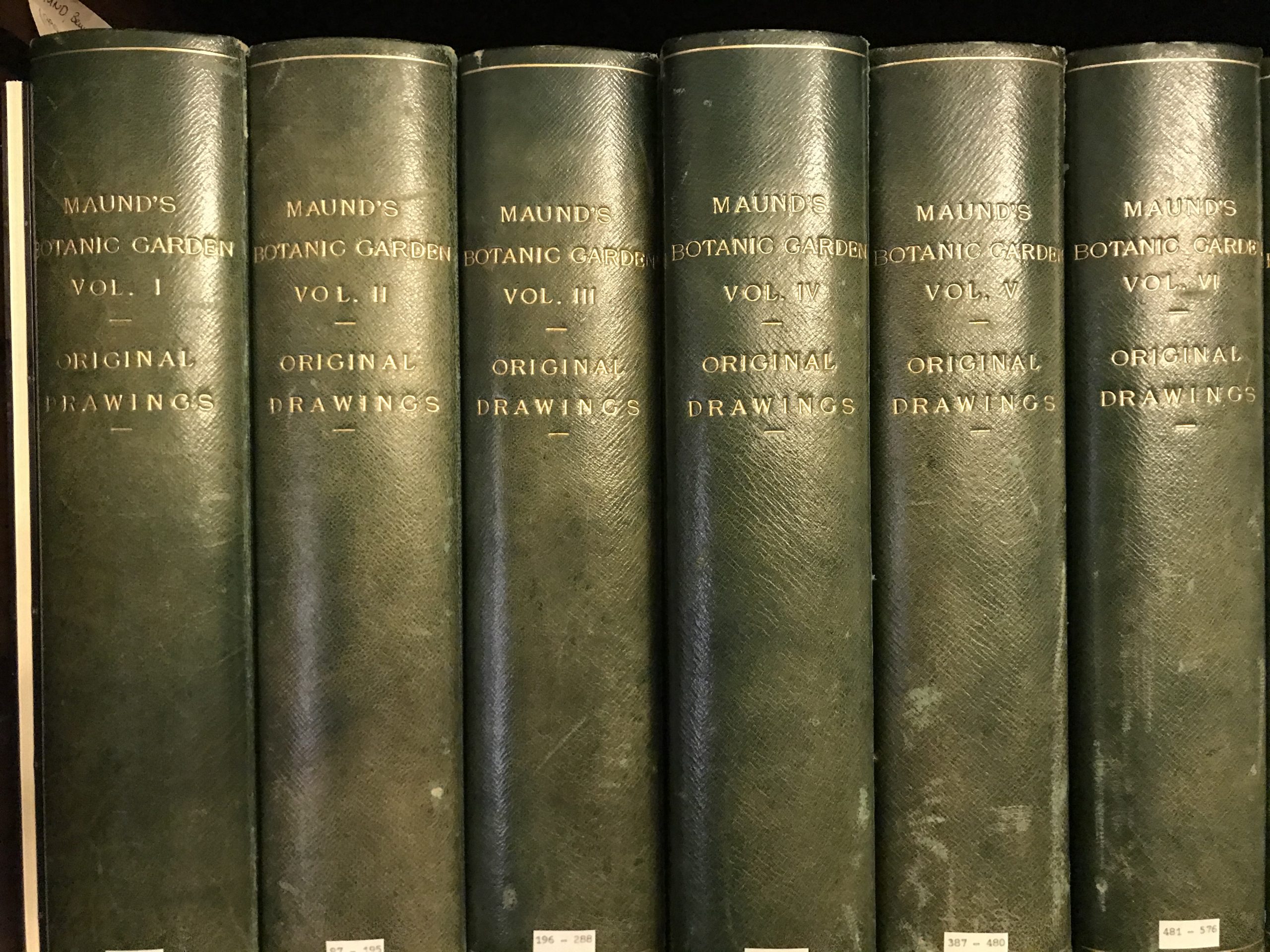

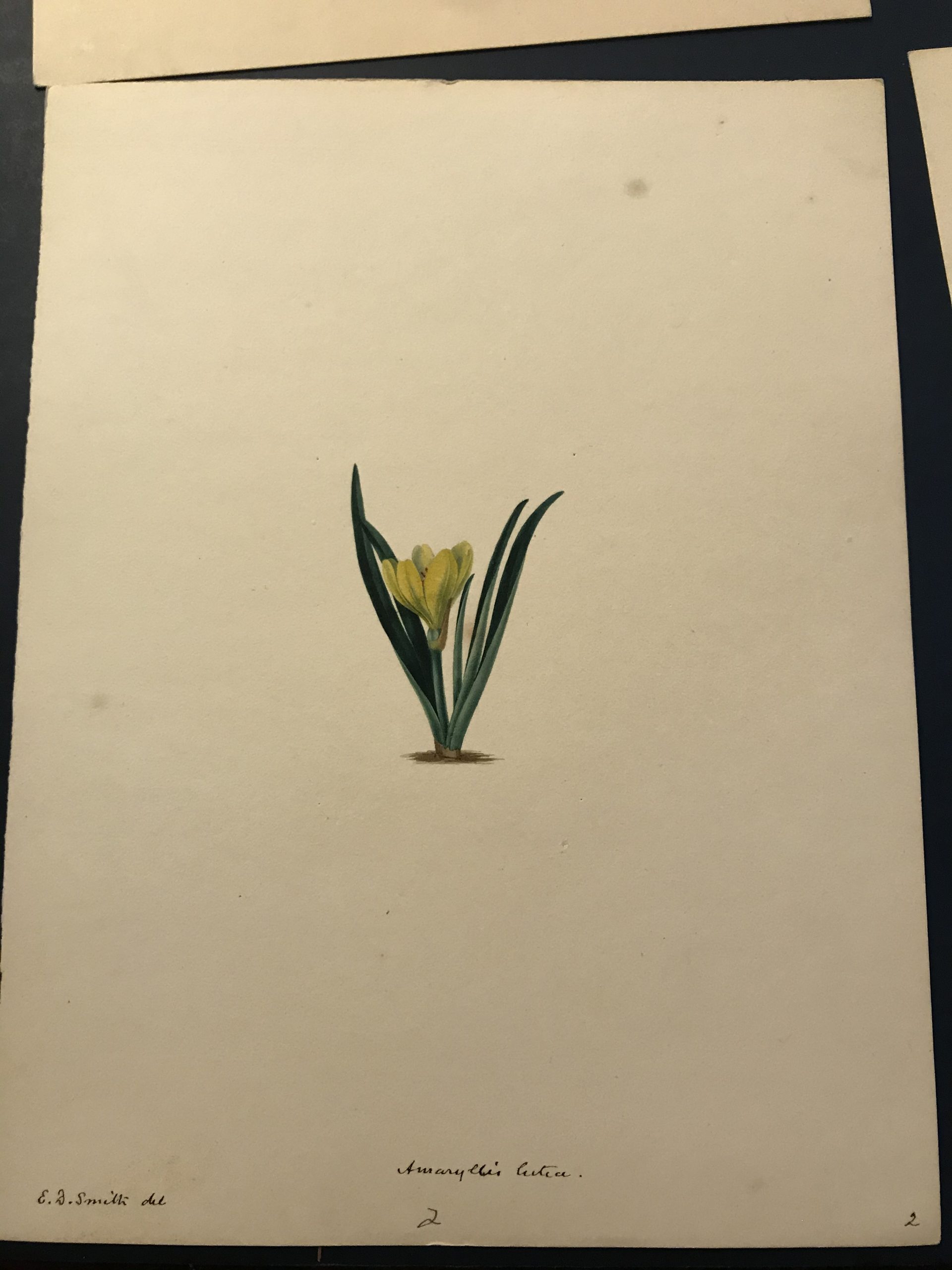

13 Volumes of Original watercolours from Maund’s The Botanic Garden at NHM Library Special Collections Botany Drawings CUPD 12

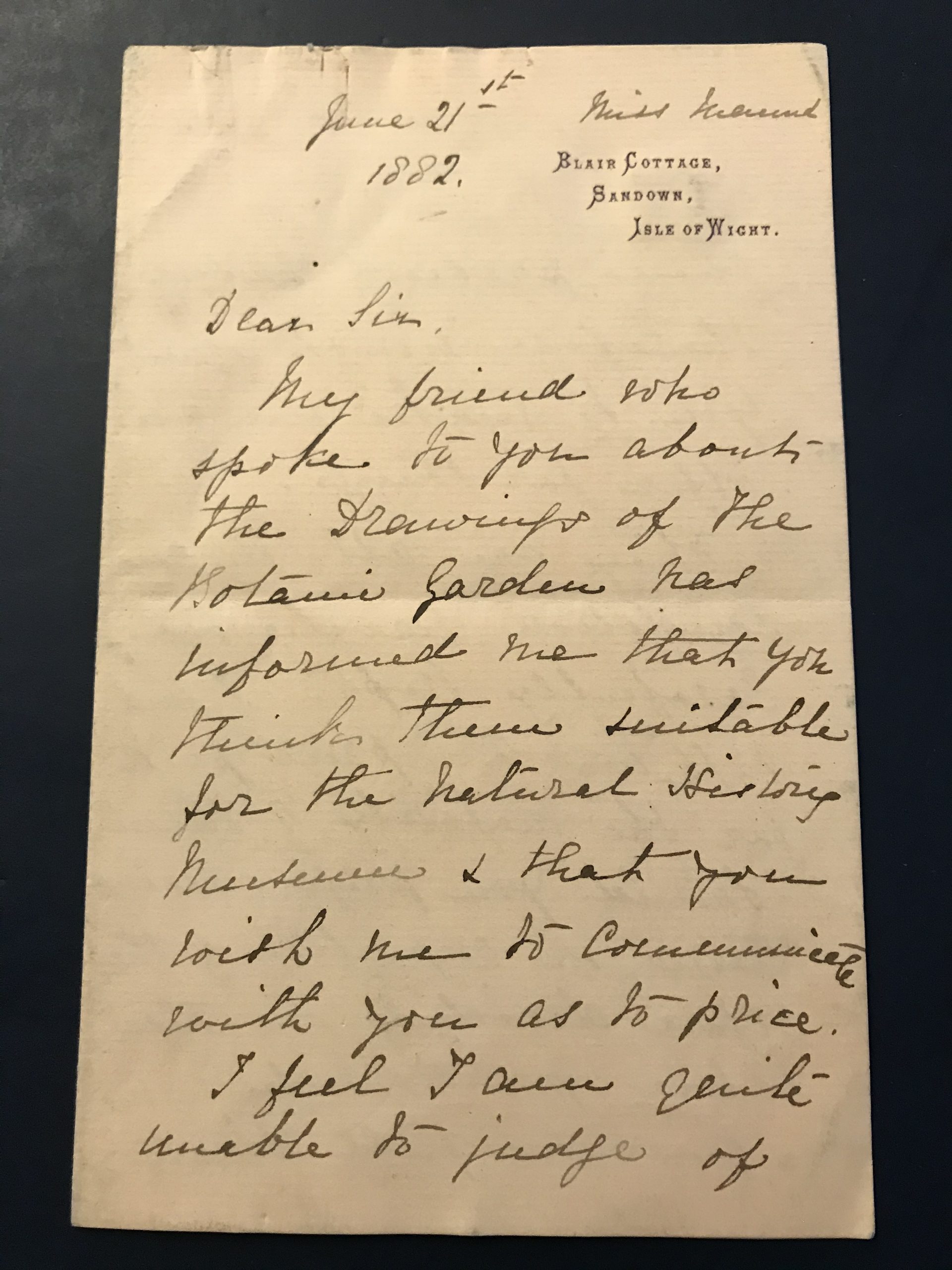

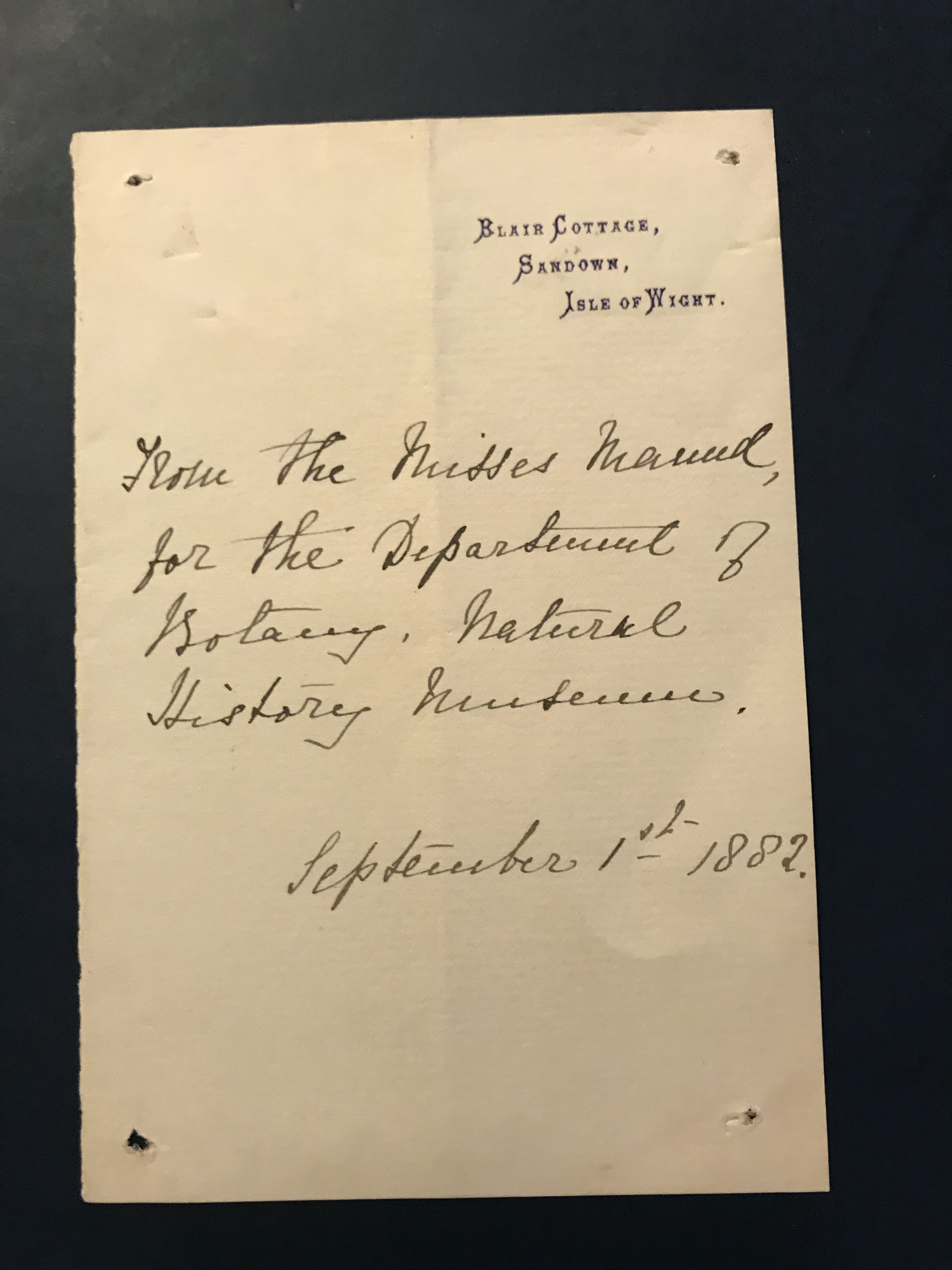

Indeed the original drawings of the plates were later bequeathed to the Natural History Museum by his daughter Sarah as shown in a letter dated 21st June 1882, Sandown, Isle of Wight to the Keeper of the Botanic Department, only a year after the museum first opened in South Kensington.

Letter from Sarah Maund dated June 21st 1882 to the Keeper of Botanical Dept. at the Natural History Museum

She writes ‘I feel I am quite unable to judge their present value therefore must request you make me an offer for them’, going on to say in a follow up letter of the 11th July 1882 that ‘I quite understand your not advising to give a larger sum for the drawings, as they serve no purpose for a scientific view – they are simply a work of art’. Ironically, their value in understanding the development of botanical art and horticulture mean a complete collection of The Botanic Garden can now fetch thousands of pounds as reported by the Worcester News. Sarah delightfully later even refers to ‘The Misses Maund’.

Note from Sarah Maund referring to The Misses Maund to the Keeper of Botanical Dept., Natural History Museum, September 2nd, 1882

As time went on, Maund’s contribution to Bromsgrove would rival that of the fictional Ross Poldark. As a committed Anglican he served as a churchwarden for nearly 40 years, later lending the churchwardens (along with four others) £500 at 5 per cent to build a new town hall and becoming a shareholder, he served on the Board of Health, in 1853 was one of four businessman who set-up a private company to develop a new site for the cattle market and for a number of years was a director of the Stourbridge and Kidderminster Bank (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

Original watercolour of Amaryllis lutea from Volume 1 of Maund’s The Botanic Garden at NHM Library Special Collections Botany Drawings CUPD 12

Maund’s interests in science were not limited to botany either. Ever the farmer’s son, he spoke to the local farmer’s club on turnip fly and the injurious effect of trees on agricultural crops. He even experimented with wheat varieties raised in experimental crossings which he exhibited at the Royal Agricultural Society in 1846 and went as far as to urge the government to experiment in agriculture and horticulture (as farmers in Europe were doing) (Cooper, M., Isaac, 1998).

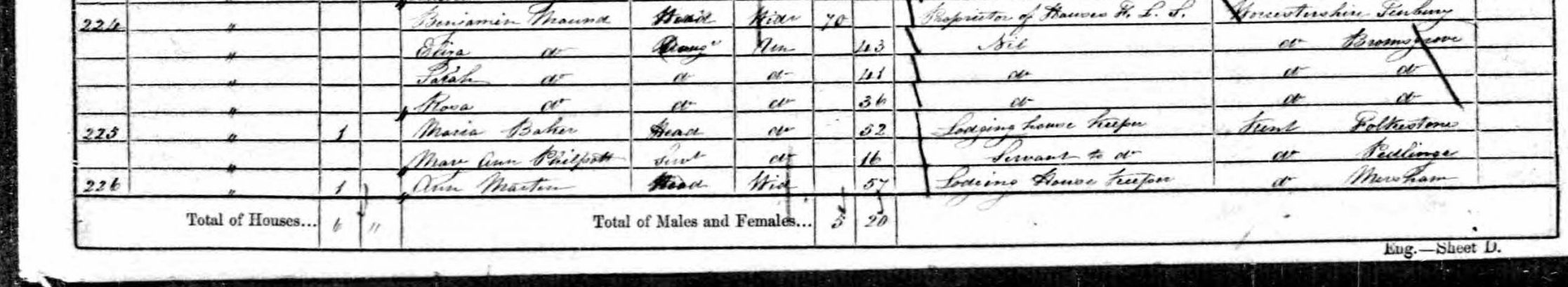

Benjamin Maund and his family on the 1861 Census

By 1861, Benjamin who is now 70 years old is a widow living in Folkestone (having lost his beloved wife Sarah in 1857) as shown on the 1861 Census at St. Mary Eanswith, Folkestone with his daughters Eliza (43) Sarah (41) and Rosa (36). He later moves to the Isle of Wight living out his life until his death on 21st April 1864. You can further explore the Maund family tree on Ancestry. Thanks to Bromsgrovians John Humpreys and Frederick Baxter a memorial plaque was presented in his memory in the Parish church in 1928 (next to the windows installed in memory of his wife and son John Maund) and was reported in the Birmingham Post on 16th April 1928.

Today (1976 and therefore over 50 years ago!) Mary Jones closes her research notes by saying ‘the Crown Close is a very uninspiring piece of municipal grass (amidst a main road!), with no mention of any sort of Maund or the flowers he once grew there. In his work, those flowers still speak eloquently of his enthusiasm – and indeed, of that of the ladies of his family, industriously colouring those exquisite plates..[..] One likes to think of them conferring there on summer afternoons, and I wish Bromsgrovians would be inspired to make it a more botanically interesting piece of ground, in memory of the Maunds’.

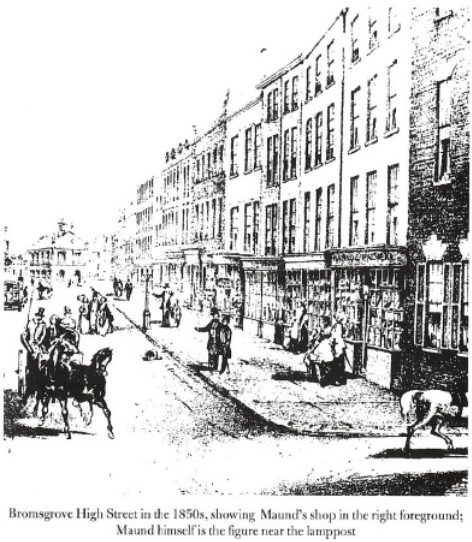

Bromsgrove High Street in the 1850’s in The Reach of Print, (Cooper, M., Isaac 1998)

Anthony Roach F.L.S.

Special thanks to Teresa Jones and Hellen Pethers at the Natural History Museum for their kind assistance with research.

Sources & Further Reading:

A Snuff-Box from the King of Prussia: The Remarkable Career of Benjamin Maund, Bookseller, Druggist and Botanist: Margaret Cooper in:

The Reach of Print: Making, Selling and Using Books

Isaac, Peter and Barry McKay (editors), Oak Knoll Press & St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1998.

Maund, B. F.L.S., The Botanic Garden, Vols 1-13, London., Simpkin, Marshall, and Co. Stationers’ Hall Court : Sherwood and Co., Paternoster Row.

James Britten, ‘Bibliographic Notes.’ LXXIII. Maund’s The Botanist (1836-1842), Journal of Botany, 56 (1918) 241, Natural History Museum, Library & Archives Service

[13 volumes of original watercolours of ornamental flowering plants for the illustrations in ‘The Botanic Garden’, 1825-51] Library Special Collections Botany Drawings CUPD 120, Natural History Museum, Library & Archives Service

Post a Comment