Redditch Tribunal Project: Employees and Employers

- 19th April 2021

In this blog we will consider those applicants to the Redditch Military Service Tribunals who we know of as primarily employees, either because they held exemption certificate for the whole of the war due to their jobs, or because we have not located military records. We will also look at who employed them. We have included a couple of case studies of workers in Redditch whose stories illustrate the increasing demand made on those workers who were exempted from fighting.

Employers

Overall, we have counted 216 different employers, covering 801 workers. However, some men had multiple employers as they either had several jobs at the same time, or because they switched employers during the course of the Tribunals, so this number includes some people twice. For others we have no employer listed either because it was not recorded, they worked for themselves or their applications were not relating to their employment.

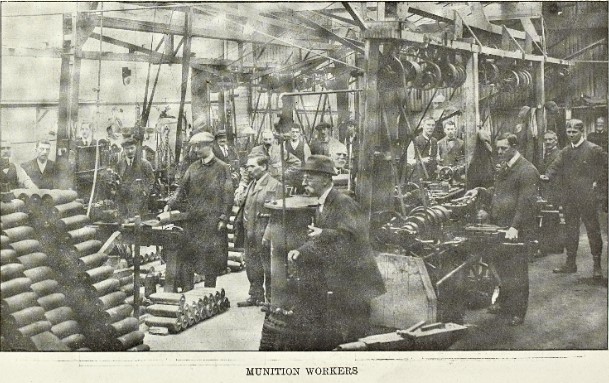

Therefore at least 80% of individuals seen by the Redditch Local Tribunal had applied for an exemption based on their employment. The biggest employer represented at the Redditch Tribunal was Henry Milward & Sons, who over the course of the registers had 104 of their employees apply for an exemption; Samuel Allcock & Sons had 80 employees and Abel Morrall Ltd. had 46 employees apply. The most common industry amongst applicants therefore was needle and hook manufacturing, but there are also applications from the spring, motor, building, food, and paper industries amongst others. Many of these firms were also repurposed to perform essential war work including munitions, as well as fulfilling government contracts. We have added an index of the names of all the employers we found represented in the Tribunal Registers to our resource section on our website at the link below.

Munition Workers: Berrow’s Illustrated Supplement 3 June, 1916.

Case studies

Below are a few case studies of workers in Redditch whose stories illustrate the increasing demand made on those workers who were exempted from fighting.

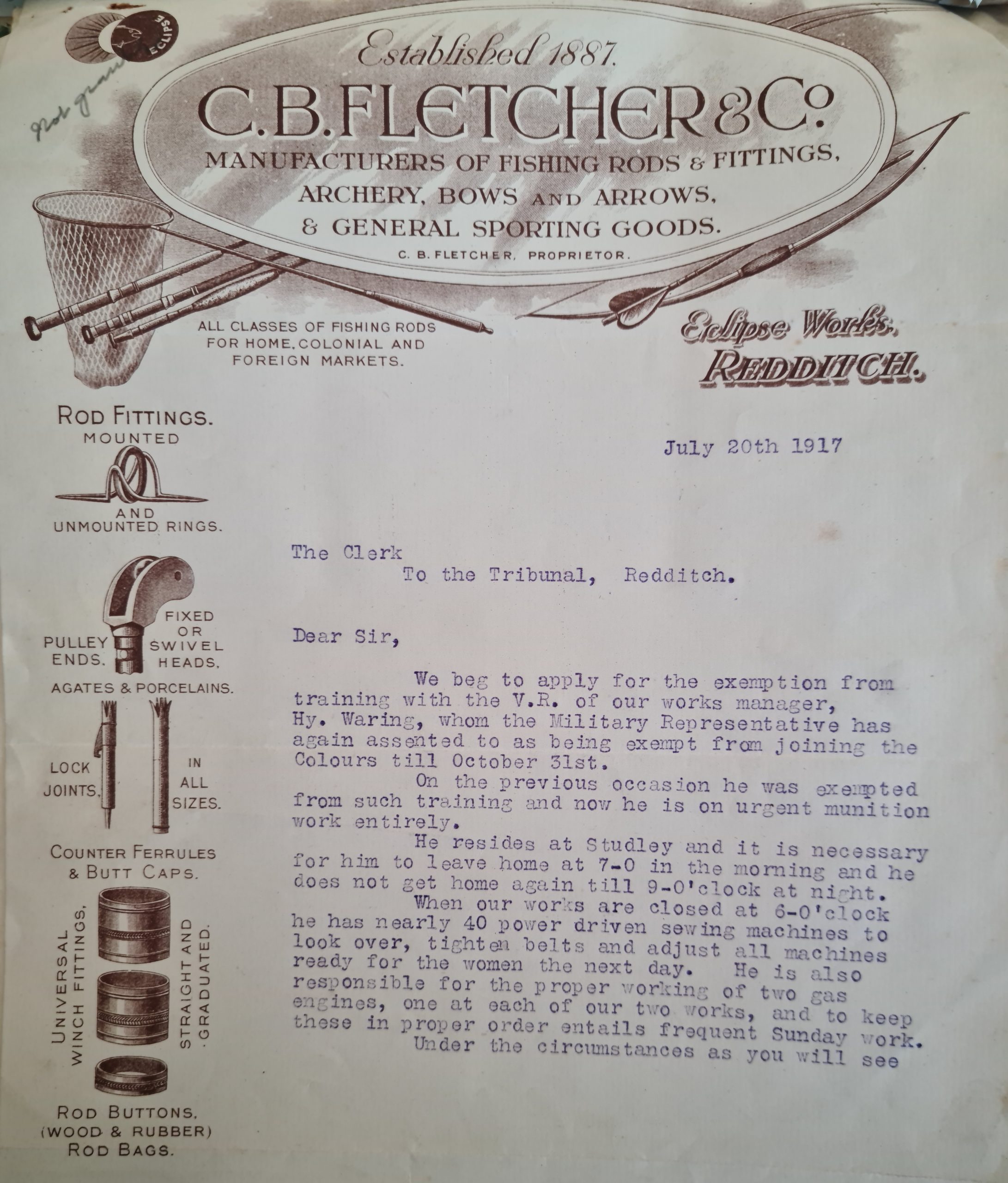

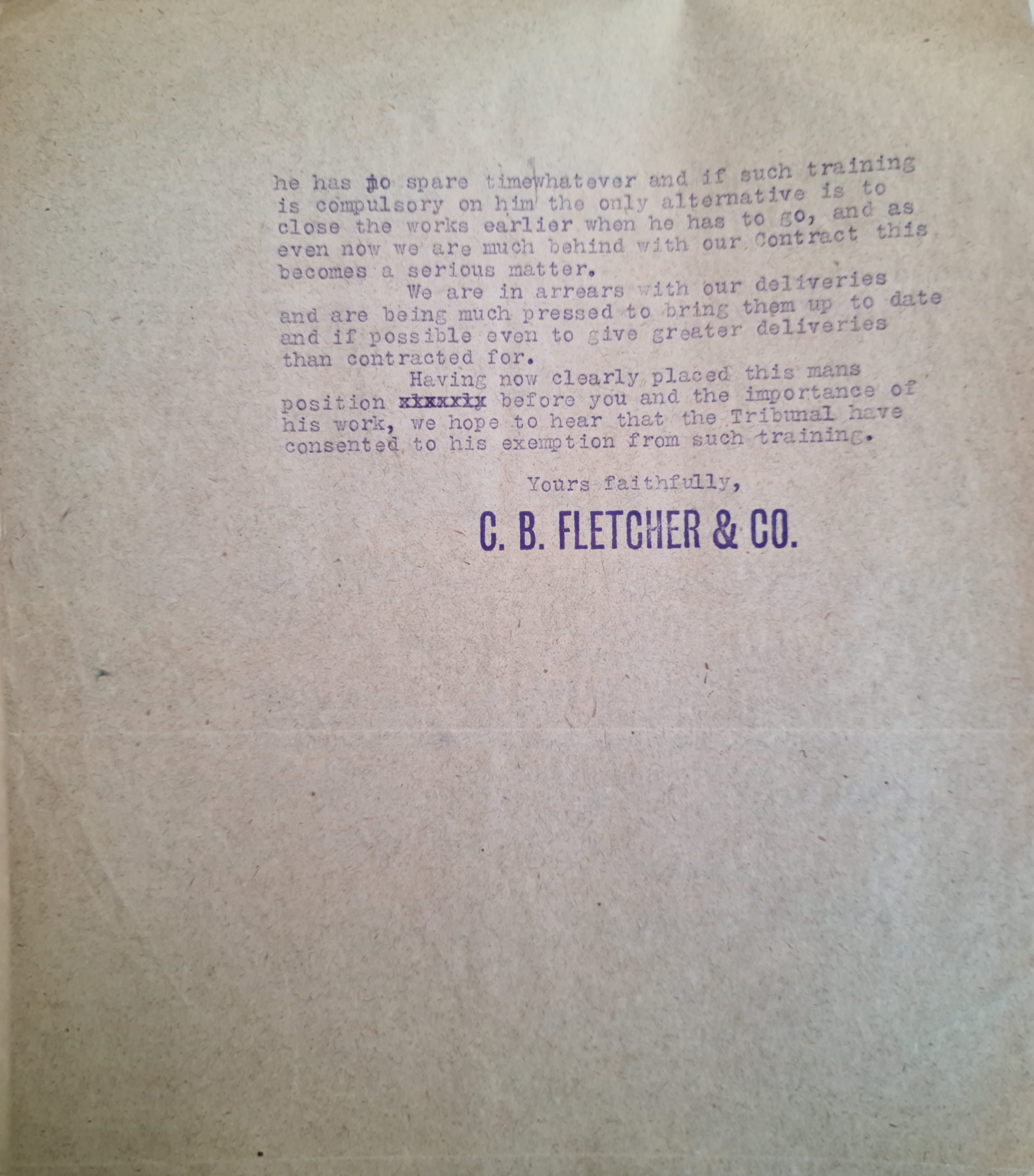

Henry Waring was a works manager at C.B. Fletcher & Co. fishing tackle manufacturers. He attested under the Derby Scheme in 1915 and applied in February 1916 for an exemption; however, due to the proximity of this application to the enforcement of the new Military Service Act, his form was returned. As a result, Henry’s first true hearing was on March 22, 1916 under the Military Service Act at which time he was given an exemption until the end of June 1916. Henry was given exemptions through to the end of October 1917 with the usual condition of training with the Volunteer Training Corps or Volunteer Regiment as it was sometimes known. What happened following this last exemption is unclear, we did not locate military records so he may have received a War Badge and continued his role at C.B. Fletcher & Co. as he was undertaking ‘urgent munitions work’ by 1917, or his military record may have been lost.

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service BA10917/33(i)/1: Letter dated July 20, 1917

In a letter from Henry’s employer to the Tribunal dated July 20, 1917 they request an exemption for him from training with the Volunteer Regiment due to the amount of work he was doing, which left him little time to train. Henry lived in Studley and left home at 7am every morning, not arriving home until 9pm:

“When our works are closed at 6-0’clock he has nearly 40 power driven sewing machines to look over, tighten belts and adjust all machines ready for the women the next day. He is also responsible for the proper working of two gas engines, one at each of our two works, and to keep these in proper order entails frequent Sunday work.”

The company argued that they had to close their factory early when he had to train, but they were already behind with their contracts and it was damaging to do so. This letter demonstrates that men who were left working in some industries ended up doing the work of several others as well as their own; Henry worked in munitions by day and in the evening and at weekends maintained the equipment needed to keep the works running.

Worcester Volunteers off for a field day: Berrow’s Illustrated Supplement April 29, 1916

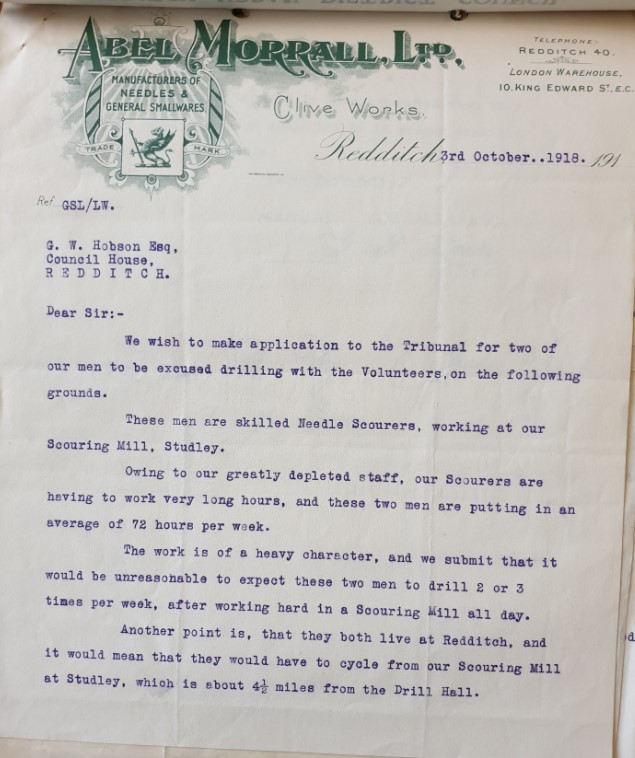

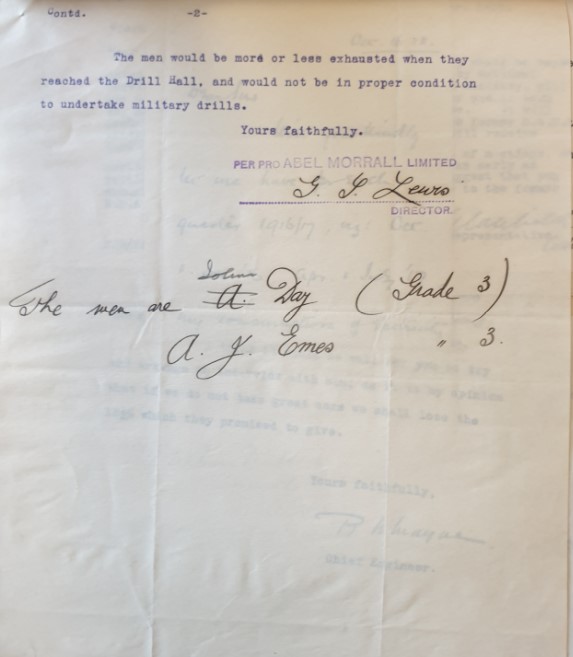

In another case study John Day and Albert James Emes share a similar story and were close in age. They both worked for Abel Morrall Ltd. as needle scourers in 1911 and continued in this work through to 1916 when the Tribunals started. The applications for both John and Albert were submitted by their employer and their serial numbers regularly follow on from one another or are very close together in the registers. Abel Morrall submitted the applications for all their employees on their behalf and did so in batches, receiving similar temporary exemptions for many of their employees.

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service BA10917/34(ii)/2: Letter dated October 3, 1918

Both John and Albert were given exemptions, with the condition that they train with the Volunteer Regiment until June 1918 where they were relieved from this training. One their next application a letter from Abel Morrall requests a further exemption for them from training, explaining that by October 1918 both men were working 72 hours a week at heavy labour due to the reduction in staff at the works; they would then need to cycle 4.5 miles to the drill hall in order to train. Their employer argued that they would be so exhausted that they would not be ‘in proper condition to undertake military drills’. The last application from Abel Morrall for both these men was submitted on November 16, 1918 and as such no hearing needed to take place due to armistice on November 11, 1918.

Both these case studies provide us with an insight into the lives of those exempt from Military service due to their professions. Such exemptions did not mean that the men had an easy war, in many cases the work they did was very difficult, tiring, and stressful due to a reduced workforce and the increased hours and responsibilities placed on them because of this. Above all though it was essential work which kept the military machine and economy in operation.

See our project page for links to other stories about the Redditch Military Tribunals.

Post a Comment