Titanic – Samuel Ernest Hemmings – Crew member

- 6th May 2021

Samuel Ernest Hemming, originally from Bromsgrove, was a member of the crew, working as a lamptrimmer on the Titanic. Samuel was one of the first people to realise the ship was sinking after it hit the iceberg. He was rescued on a lifeboat and spoke in the American investigation before returning home to his family in Southampton. He was a lamp trimmer, ensuring the lights were lit on board and keeping them lit throughout the nights. This was quite a manual role involving 73 under-trimmers on the Titanic, only 20 of whom survived the sinking. He was ordered to ensure all 15 lifeboats had lit oil lamps, making it easier for survivors in the water to be seen by rescue ships.

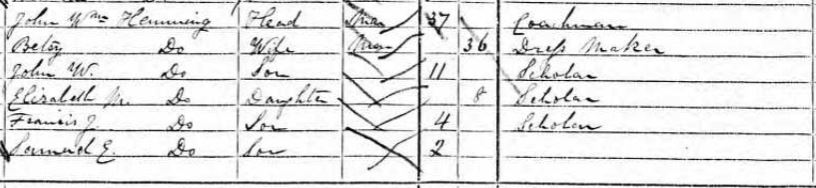

Born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, on 24 December 1868, Samuel Ernest Hemming was baptised in February the following year, the son of John William Hemming (1834-1894), a coachman of Bromsgrove, and his wife Elizabeth “Betsy” (b. 1835), of Droitwich. His father had previously appeared on the census as an ostler (1861) and a groom (1851). His mother was a dressmaker. Samuel had seven siblings, John William (b. 1859), Frank (b. 1861), Elizabeth May (b. 1862), Ellen (b. 1864), Francis Joseph (b. 1866), Harry (b. 1870) and John Walter (b. 1879). They lived first at New Road near Catchems End Bromsgrove, and by the 1881 census had moved to Francis Yard on Bromsgrove’s High Street, which included four properties near the Golden Cross Hotel now at 20 High Street.

Census 1871 crown Copyright

Samuel’s Career

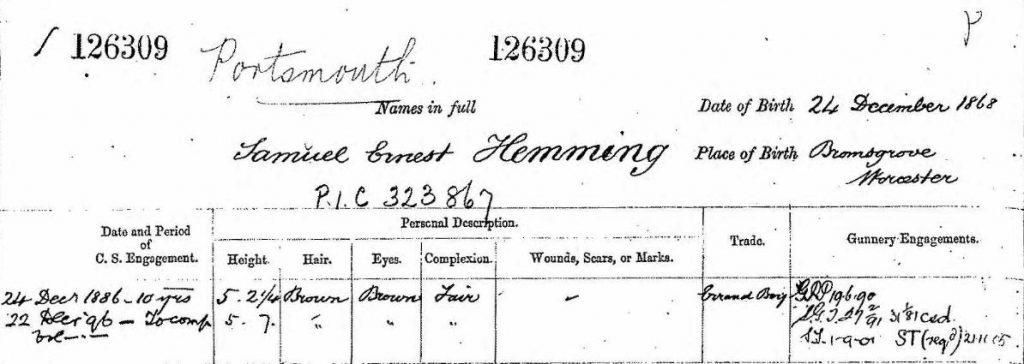

In his youth Samuel worked as an errand boy before he joined the Royal Navy on 12/2/1884 at just 15, based in Southampton. He was just 5”2’with brown hair and eyes and his first ship was impregnable. He would also serve aboard Lion, Leander, Duke of Wellington, Excellent. By the 1891 census he was aboard at Brompton, Kent with the Royal Navy, with other men on board Mildurn, and by now he was an Able Seaman. He also served on the Curacoa, Victory I, Vernon and Boscawen. When on board SS. Powerful his wages were to be paid to his brother Francis. He also served on the Clyde, Cossack, Triumph, Revenge and Mercury. In 1899 Samuel was awarded the Queens South Africa medal and Kings South Africa medal for serving in the Anglo Boer War on SS Powerful.

Samuel married Elizabeth Emily Browning (b. 30 August 1881) in Portsmouth in 1903 before they moved to Southampton and went on to have three children at 51 Kingsley Road, Shirley, Hampshire, Ernest Harry (b. 1904), Jessie Dorothy (b. 1906) and Thomas Robert (b. 1909).

He went to work for the White Star Line in 1907 when he was pensioned off from the Navy, by now standing at 5”7’. He served aboard Teutonic, Adriatic and Olympic as boatwain’s mate, lamp trimmer and boatswain. His family were shown on the 1911 census living at 51 Kingsley Road, Shirley, Hampshire where Samuel was described as a naval pensioner seaman.

Hemming served on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. He was a Lamp Trimmer, responsible for keeping the lamps in order and burning in all weather conditions. Such skilled men were employed in town streets, for railway companies and very large houses. On-board a ship a ‘lamp trimmer’ took care of both the cabin and navigational lights working in all weathers and situations. He worked from a small room known as a ‘lamp locker’ containing tanks of oil, rolls of wick, chimneys, burners, scissors, reflectors, and cotton waste for cleaning purposes as well as spare lamps, including the boat lamps which were square lamps about 10 inches high that burnt Colza oil. The lamp trimmer was often given the nickname of ‘Lamps’ or ‘Lampey”, and he had to be a very competent seaman.

Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services; at The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey

Samuel’s Testimony

Interestingly we can quote Samuel Hemming in his own words because he gave evidence on day 7 of the United States Senate Inquiry to chairman Senator Smith. On his return to Britain he also testified for the British enquiry on 24 May 1912.

Samuel described his duties on the Titanic as mixing “the paint, and all that kind of thing for the ship, and to look after all the decks, trim all the lamps, and get them in proper order. That is all, I think. To put the lights in at nighttime and take them off at daybreak.”

On the night of the accident he was in his bunk asleep. he was awakened by the impact. He said, “I went out and put my head through the porthole to see what we hit. I made the remark to the storekeeper “It must have been ice.” I said, because I could not see anything… I went up under the forecastle head to see where the hissing noise came from… I opened the forepeak storeroom; me and the storekeeper went down as far as the top of the tank and found everything dry… I came up to ascertain where the hissing noise was still coming from. I found it was the air escaping out of the exhaust of the tank… At that time the chief officer, Mr. Wilde, put his head around the hawse pipe and says: “What is that, Hemming?” I said: “The air is escaping from the forepeak tank. She is making water in the forepeak tank, but the storeroom is quite dry.” He said, “All right,” and went away.

“We went back in our bunks a few minutes. Then the joiner came in and he said: “If I were you, I would turn out, you fellows. She is making water, one-two-three, and the racket court is getting filled up.”… Just as he went, the boatswain came, and he says, “Turn out, you fellows,” he says; “you haven’t half an hour to live. Keep it to yourselves, and let no one know

“It was about a quarter of an hour, from the time the ship struck… I went on deck to help to get the boats out. On the port side… My station was boat No. 16 on the boat list… I went and helped turn out; started with the foremost boat, and then worked aft… I went on the boat deck. They were turning the boats out. As I went to the deck, I went there where were the least men, and helped to turn out the boats… Then I went to the boats on the port side, to do the same, until Mr. Lightoller called me and said, “Stand by to lower this boat.” It was No. 4 boat. We lowered the boat in line with the A deck

“I had an order come from the captain to see that the boats were properly provided with lights. I went away into the lamp room lighting the lamps, and I brought them up on deck. Then I lit the lamps and brought them up, four at a time, two in each hand. The boats that were already lowered, I put them on the deck, and asked them to pass them down to the end of the boat fall. As to the boats that were not lowered, I gave them into the boats myself. For the boats that were not lowered, I gave them to somebody in the boats… After I had finished with the lamps, when I made my last journey they were turning out the port collapsible boat. I went and assisted Mr. Lightoller to get it out…

“I went along the port side and got up the after boat davits and slid down the fall and swam to the boat and got it… about 200 yards… With no a lifebelt on… [at the lifeboat I] tried to get hold of the grab line on the bows, and it was too high for me, so I swam along and got hold of one of the grab lines amidships. I pulled my head above the gunwale, and I said, “Give us a hand in, Jack.” Foley was in the boat. I saw him standing up in the boat. He said, “Is that you, Sam?” I said, “Yes;” and him and the women and children pulled me in the boat… It was full of women. With four men these were Quartermaster Perkis, and there was Foley, the storekeeper, and McCarthy and a fireman, two young ladies and a little girl. I did not see the babies at all when I got in the boat. About 40, all told, I should think, at that time.

“They had been backing her away, to get out of the zone from the ship before the ship sank… After the ship had gone we pulled back and picked up seven. Stewards, firemen, seamen, and one or two men, passengers; I could not say exactly which they were; anyway, I know there were seven, there was one seaman named Lyons, and there were one or two passengers and one or two firemen. Dillon, a fireman, was one of them. I know one was a third class passenger. He spoke very good English, but I have an idea that he was a foreigner of some sort… They swam toward the boat, and we went back toward them.

“We hung around for a bit [because] we did not know what to do… We heard the cries; yes, sir. We were moving around, constantly, sir. Sometimes the stern of the boat would be toward the Titanic, and sometimes the bow of the boat would be toward the Titanic. One moment we would be facing one way, and a few moments later we would be facing another way; first the bow, and then the stern toward the ship.

“We made for a light… one of the boats’ lights. We pulled toward them and got together, and we picked up another boat and kept in her company. Then day broke and we saw two more boats. We pulled toward them and we all made fast.

“We heard some hollering going on and we saw some men standing on what we thought was ice. Half a mile, away as nearly as I can judge. Twenty, I should think. Standing On the bottom of this upturned boat… Two boats cast off – us and another boat cast off – and pulled to them, and took them in our two boats… [Second Officer] Mr. Lightoller was on the upturned boat…

“We pulled away. We went away a bit. Then we pulled up until we saw the Carpathia, and we pulled to the Carpathia. It was daylight then. All passengers were got board. Then I went on board myself, sir…. [we] saw icebergs that morning… not very large… About a moderate size, I should think they would be 12 or 14 feet. And field ice extended right across, as far I could see, sir. It was cold… It made my feet and hands sore.

Titanic departing Southampton on 10 April 1912

After the Titanic

Hemming was later reunited with his family and soon returned to sea.

As the First World War began, Hemming rejoined the Navy in August 1914. He rejoined Victory and served throughout the duration of the conflict as 1st Class Petty Officer, mine-sweeping. He served aboard Roedeau which was struck by a mine and sank in January 1915 but he escaped. He joined the Whitby Abbey in July 1915. His last ship was Victory I before he was discharged in March 1919 and he was decorated with the General Service and Victory Medals.

After the war he returned to work on merchant ships. He travelled on the White Star Line’s Olympic as a storekeeper. He sailed on the same ship in July, September and October 1920, March June August and October 1921. He transferred to the Homeric still with the White Star Line as Petty Officer, sailing in August 1923, June 1925, September 1926, and November 1927

Samuel spent his last years living at 47 Cecil Avenue in Shirley before he moved to Blighmont Nursing Home. He passed away on 12 April 1928 aged 59. His widow Emily who was with him when he died married in 1929, to Edwin J. Courtney, but when she died in 1940 she was buried with Samuel in Hollybrook Cemetery in Southampton.

Samuel’s daughter Jessie was never married and had already died in 1924. His son Ernests and Thomas married and lived in to the 1980s.

Hemming’s set of keys from the Titanic were sold at an auction at Christie’s in London in 2016, for £20,000. The keys bear a brass tag bearing the words “Lamp-trimmer and Storekeeper”. Auctioneer Andrew Aldridge said: “The keys themselves played a part in the story as they were actually used in those last desperate hours.

NOTES:

Tibballs, Geoff (Ed), Voices From The Titanic: The Epic Story Of The Tragedy From The People Who Were There

Alastair walker, Four Thousand Lives Lost: The Inquiries of Lord Mersey into The Sinking of the Titanic, The Empress of Ireland, The Falaba and the Lusitania

encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-survivor/samuel-hemming.html, titanic.fandom.com/wiki/Samuel_Ernest_Hemming, irishtimes.com/news/titanic-keys-to-be-sold-at-auction-1.704922, news.justcollecting.com/titanic-keys-bring-20-000-in-christies-out-of-the-ordinary-sale/, nolamackey.wordpress.com, Titanicinquiry.org

Museums Worcestershire have an exhibition, Titanic: Honour and Glory, running from Monday 17 May – Saturday 11 September. Our Titanic letter will be part of this.

Post a Comment