Willing Worcestershire

- 5th August 2021

Rhonda, our Conservator, does amazing things to repair and conserve our documents and ensure they last and can still be available for people to use. Currently she is working on 15 boxes of wills, thanks to funding from National Conservation of Manuscripts Trust. We caught up with her and asked her about what is involved, and to take us through the process of conserving one document.

After a stop-start year in Conservation, it’s great to be back in the studio and getting my hands wet on some very satisfying Conservation work.

After a stop-start year in Conservation, it’s great to be back in the studio and getting my hands wet on some very satisfying Conservation work.

In November WAAS was successful in being awarded a grant from the National Conservation of Manuscripts Trust (NCMT) to work on our collection of Wills. Consisting of over 1050 boxes, the collection includes Wills, Inventories, Letters of Administration and other papers relating to the Consistory Court of the Bishop of Worcester and the Worcester Probate Registry, dating from 1493. They were deposited at the Worcester Record Office in 1958, after spending 30 years at the Birmingham Probate Registry following closure of the Worcester Probate Registry in 1925.

Over their many years of life, the items have suffered from prolonged poor storage which has resulted in a combination of damage, including areas where the paper is powdery/flaky and susceptible to further damage when handled, however carefully, as well as water staining, surface dirt and creasing. Insect and rodent damage are evident on some items. Surface dirt and creases make the documents difficult to read, whilst attempts to remove creases may result in further damage with potential loss to the document.

Some conservation work has previously been carried out on the collection. A total of 308 boxes dating from 1493 to 1611 have been flattened and backed onto laid paper. Conservation records of this work are vague but suggest work was carried out on an ‘ad hoc’ basis with work progressing chronologically through the collection. No further work has been carried out since at least 1998. Approximately 175 boxes dating from 1611-1676 remain in such a fragile condition that they cannot be issued in the searchroom. Researchers are encouraged to use self-service microfilmed copies of the material for consultation, however original material is referred to when the microfilm is of poor quality. However, significant gaps exist in the microfilmed material where the items were too fragile to be filmed.

NCMT funding will allow 15 boxes of Wills to undergo conservation treatment, enabling the documents to be consulted for the first time in many years. Treatment involves gently removing surface dirt with a latex smoke sponge or soft brush, and then washing and repairing the damaged papers. Due to the age of the documents, all the paper is handmade, which tends to be of a higher quality than modern mass-produced paper. This means it responds well to conservation treatment and produces a good result which will hopefully keep the documents in good condition for at least another 400 years.

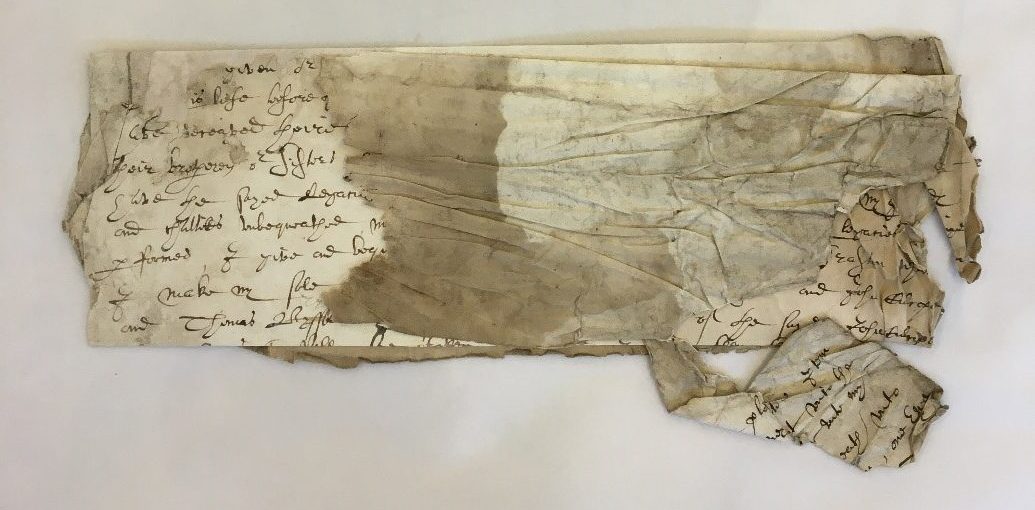

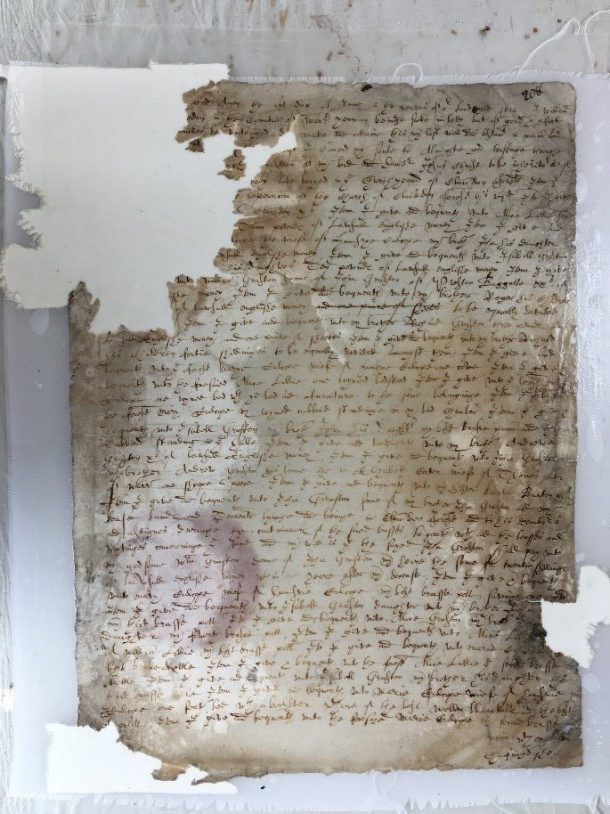

Below, I have followed William Grafton’s will ( document 008:7 BA3585/166/208) on its journey through Conservation treatment, from woe to wow.

The document as it came out of the box – folded, creased, surface dirt, water staining and even a bit of rodent damage to the right-hand side.

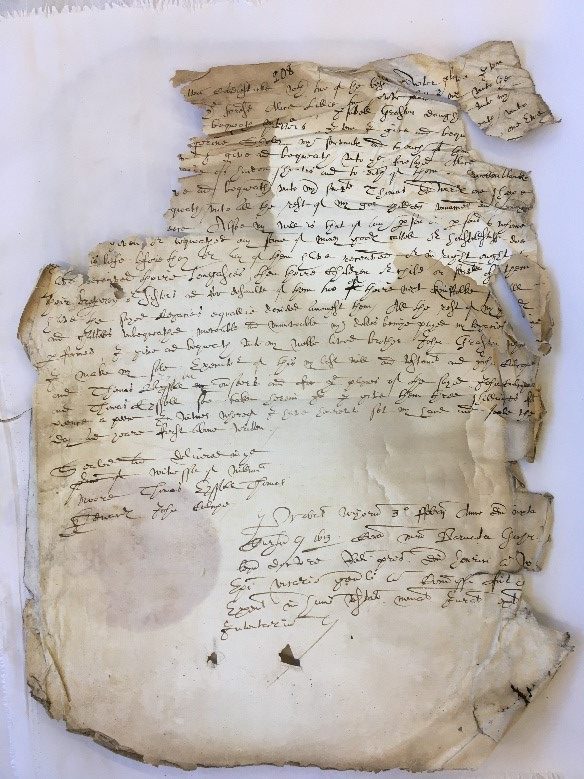

The document was carefully unfolded and then cleaned using a latex smoke sponge to remove the surface dirt. It was then placed on a piece of fabric to support the document prior to submerging it in a tray of water to wash out impurities and dirt it has picked up over the years. The fabric support also has the advantage of keeping any fragments that may be dislodged during the washing process with the appropriate document – it really is no fun trying to re-unite small pieces of document when I have no idea which one it has come from!

The document had a cold wash followed by a hot wash, resulting in the water being turned from clear to yellow, which is always very satisfying to see! At this point, the question is always ‘Why doesn’t the ink run?’ It’s all to do with the composition of the inks. On documents of this age, the ink is made from varying recipes based on oak galls to produce what is known as iron gall ink- that characteristic brown-black ink of old documents, often associated with a ‘halo’ around the text and the occasional area of loss where acids in the ink have ‘burned’ through the paper support. Luckily for us Conservators, the ink isn’t soluble in water, as the damage caused by the acidity gives us enough to be dealing with.

The document then went back in the tray to soak in a solution of Calcium Hydroxide. This is an alkaline solution that introduces what is called an ‘alkaline reserve’ to the paper – a chemical buffer that acts like a sponge, mopping up any acidity the paper is faced with in the future, protecting the cellulose molecules that make up the structure of the paper. The cellulose molecules are attached together in long chains, but exposure to acid breaks the joins between these molecules resulting in paper that is brittle and easily damaged when handled. After these treatments, the paper is whiter, brighter and stronger, and as it was of high-quality in the first place, these time-intensive treatments are very worthwhile as the strength and integrity of the original paper are restored.

Once it had finished in the bath and whilst still wet, I carefully straightened out folds and creases and tears to get the document as flat as possible. I then had the challenge of lining up the text as seamlessly as possible- at times this can be a bit like trying to do a jigsaw puzzle without the picture on the box. At this stage the paper is very delicate and susceptible to tearing so the fabric it is supported on allows me to move and manipulate the pieces into place, hopefully without making any more work for myself in the process.

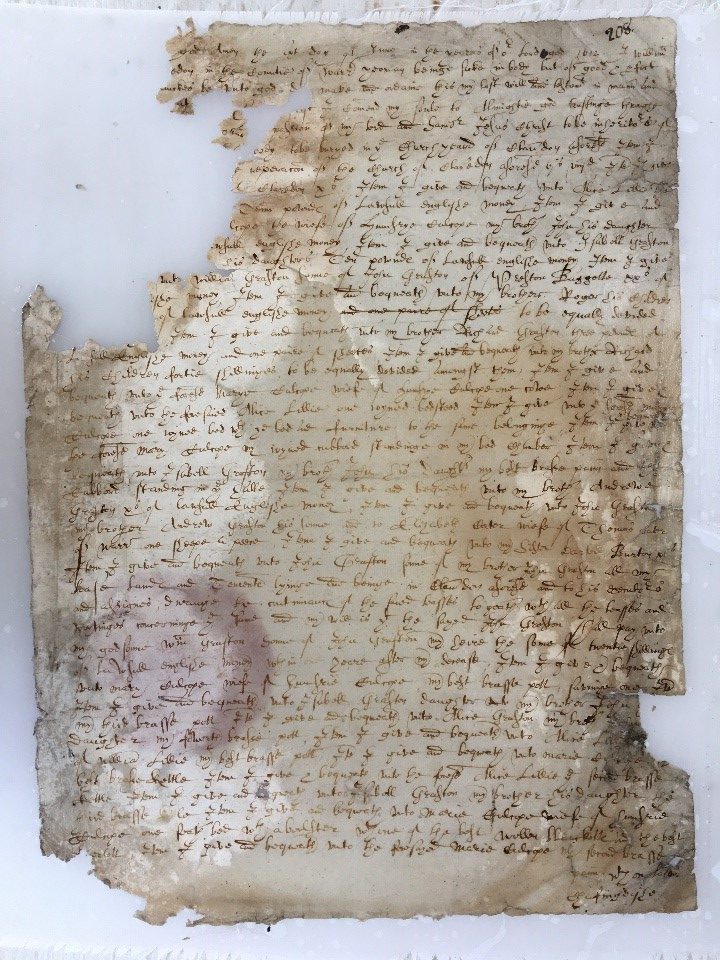

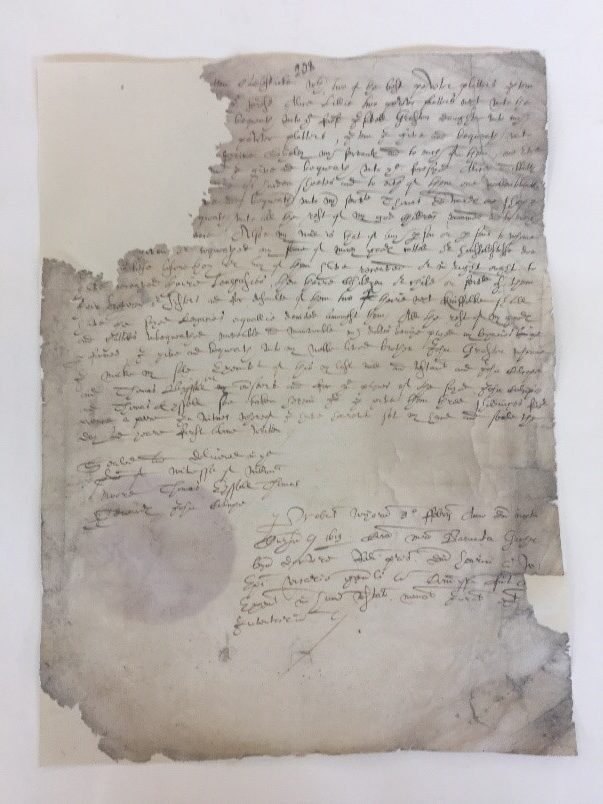

If the paper that remains is reasonably strong, I can trace around any areas of loss with the document on a light box which allows me to infill the missing area with handmade paper, with a slight overlap onto the original paper. The document was then sandwiched between a very fine layer of archival tissue which supports and protects it and then dried between sheets of blotting papers and stacked between boards over night to allow the document to dry flat.

If the document has suffered from mould damage, the remaining paper may be too weak and soft to support infilling. In this case, a layer of tissue front and back will protect the document from future damage, however there will be missing areas of paper with just the tissue filling the holes.

Once dried, the document was removed from boards, blotter and fabric support before any excess infilling paper was trimmed to size, and the document was then ready for its first outing in the searchroom for many years.

Even though I’ve done this many times in my years as a Conservator, I still find the process rather magical and love to be a small part in the life of something that has already been around longer than I ever will!

As well as working on our own archives Rhonda also does work for other archives and museums, and also for individuals. If you would like to discuss some work with us please contact Rhonda and she’ll be happy to talk to you about the work.

An example of Rhonda washing documents, similar to what she did with the wills, can be found on our Document Washing blog with a summary below below.

Fantastic work. Conservation work is time consuming but very rewarding.

I enjoyed reading this as I often look at wills in my research.