Mayflower 400: Old Worcestershire & New Plymouth (Part II)

- 22nd September 2021

After Part 1, looking at Winslow family’s Worcestershire connections, Anthony looks at the Mayflower voyage and events over on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Journey to the New World

Unsurprisingly ‘The Pilgrims’ were “constant and very vocal in religious exercise, a demonstration that some of the sailors found irritating”. However, it wasn’t long before the passengers and crew faced “common peril” in the form of a storm in the mid-Atlantic which put differences aside. A westerly gale blew up and led to an unmerciful pounding of the ship. At the height of the storm, the main beam – the structural centre of the ship, gave way under the strain. If the rough weather continued, it would almost certainly lead to the disintegration of the ship.

A reconstruction of the outer hull of Mayflower in the Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy Exhibition © The Box, Plymouth

Whether it was Providence as some of the Leydeners believed, or not, they remembered “a great iron scrue” had been brought with them. The screw was as good as the ‘jack’ known to modern engineers. They used it to successfully straighten the cracked beam, shoring it up. A legend has grown up that it was part of the dismembered printing-press (brought as a wine press or for some other purpose) from Leyden – if so, then Printer Edward Winslow may have been credited as the man responsible for the good turn in events.

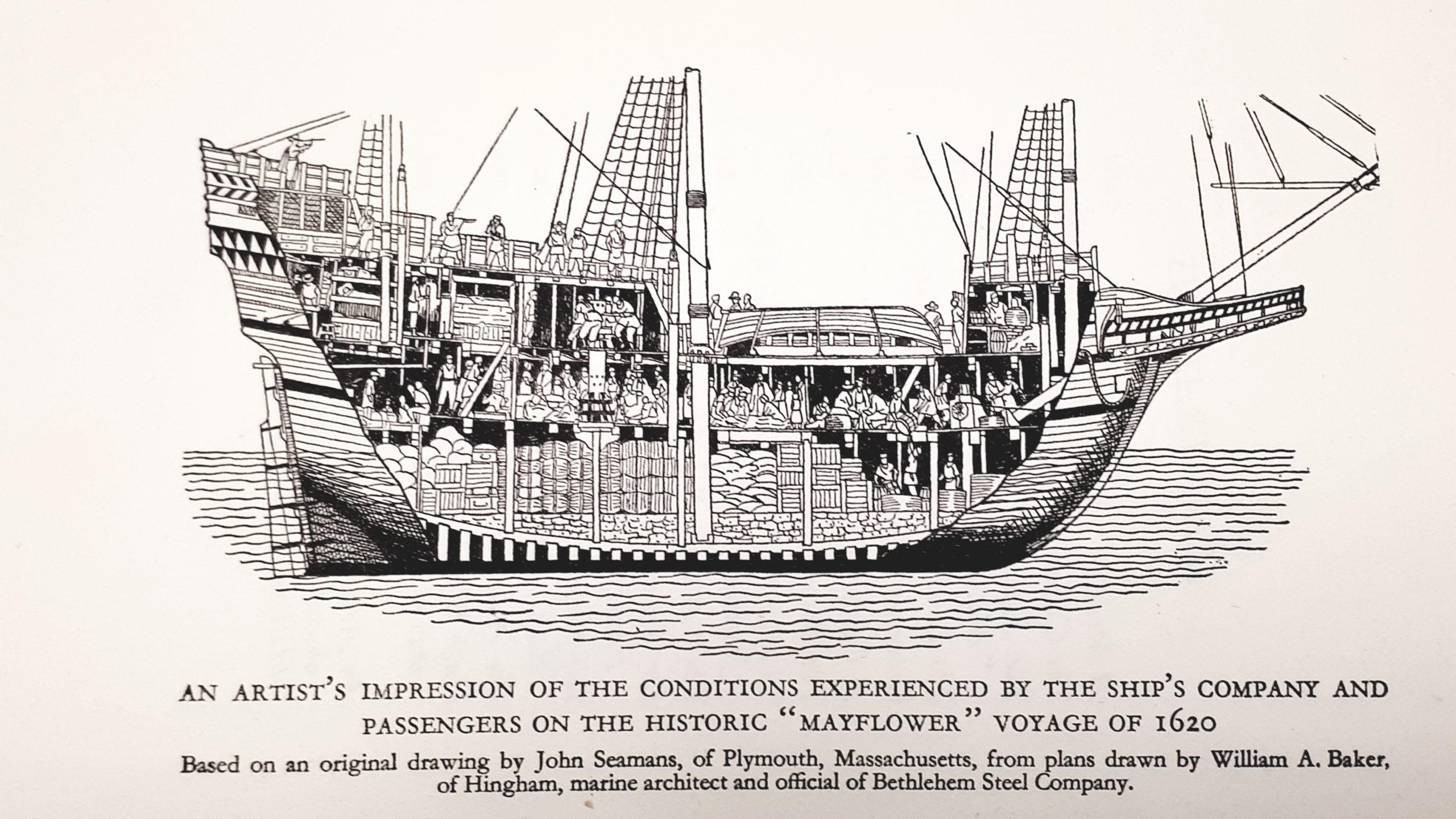

An artists’s impression of the conditions experienced by the ship’s company and passengers on the historic “Mayflower” Voyage of 1620 © D. Kenelm Winslow, 1957

Besides the cramped conditions, sea sickness and a “monotonous diet of hard tack, dried fish and other dull commodities which they washed down with beer”, there were those on-board who bullied ‘The Pilgrims’. The worst of which, along with a small boy from the Leyden group were buried at sea.

The Pilgrims ‘Compact’

Mayflower made landfall at Cape Cod on November 9th, when troubles began yet again. Amongst the crew, whilst Captain Jones was a “kindly enough man” who had been anxious for his passengers, there were those amongst The Pilgrim groups who saw the opportunity to live outside the law, these included a “malcontent who had previously visited New England”, and “others, servants and hired officers” who saw a “chance to escape from obedience to properly constituted authority”.

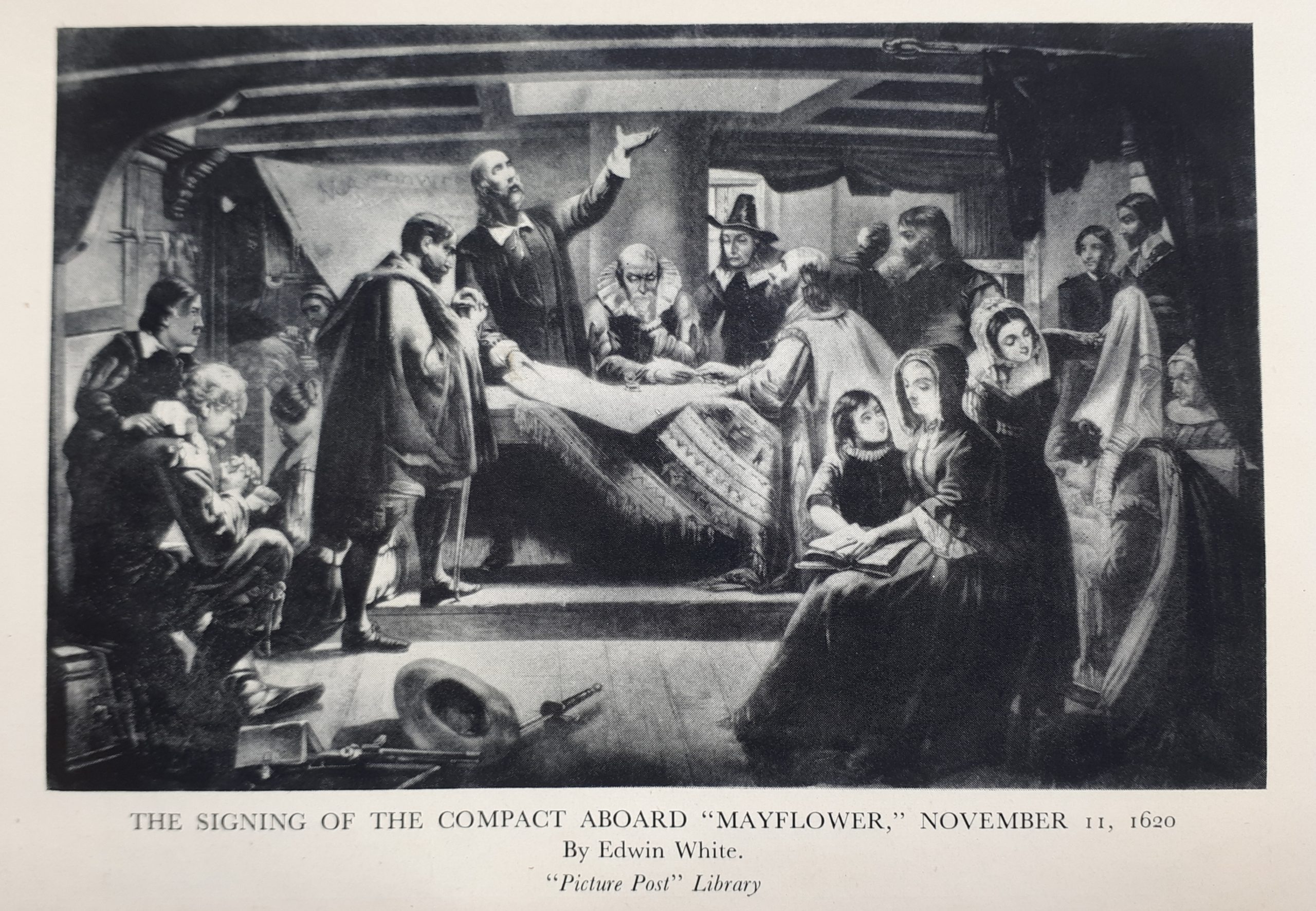

Faced with this clear and present threat amongst them and knowing that this would likely prejudice their relations with the “Salvages”, the leaders of The Pilgrims again acted with foresight in creating The Pilgrims’ Compact. Sterry-Cooper argues that 41 out of 65 male passengers signed The Compact in ‘Edward Winslow of the Mayflower’ (pg. 14) whilst the Mayflower 400 Exhibition mentions 41 out of 50 signing it. Carver was subscribed as first Governor, William Bradford the second Governor and Edward Winslow signed third on the list. There has been some speculation that Winslow himself was the clerk who wrote the Compact, though the original document appears to have disappeared.

The Signing of the Compact Aboard “Mayflower,” November 11, 1620 By Edwin White in Mayflower Heritage © D. Kenelm Winslow, 1957

With the absence of any formal laws, the Compact ensured that the community were bound by a set of principles and laws for the duration of their time in the colony and “formed the authority for the enforcement of such laws as might prove to be needed”. It has been debated whether the Compact is evidence of the bedrock of American civil liberties but what is clear is that it was drawn up without the authority of the English King and created a “Civil Body Politic”. This allowed the settlers to assume a measure of autonomy even before they landed in the New World. It was this measure of independence that arguably laid behind future disagreements with the Colonists and the Home Government until the English Revolution.

‘New Plimoth’ Harbour

After several excursions onto land, another on the 27th November was made by sea and led by Captain Jones (who like his officers and men, were anxious to return to England) and lasted three days whilst The Pilgrims hotly debated where to build their settlement. The patience of the Mayflower’s captain was further reduced when on December 5th, one of the Pilgrims’ Francis Billington fired a musket in a cabin full of gunpowder and explosives which thankfully did not lead to its destruction.

The next day ‘The First Encounter’ between the Native Americans and Carver, Bradford, Winslow and thirteen others took place as they put to shore after 18 miles (a description of the events by Edward Winslow is summarised in Edward Winslow of the “Mayflower”). They built a barricade and lit a campfire hearing hideous noises but after firing some shots the noise ceased. Arrows later flew from the Native Americans and according to Standish (and the actions of one other which may have been Winslow) the Colonists were ‘blooded’ in ‘Indian Warfare’ as one of their shots winged the leader.

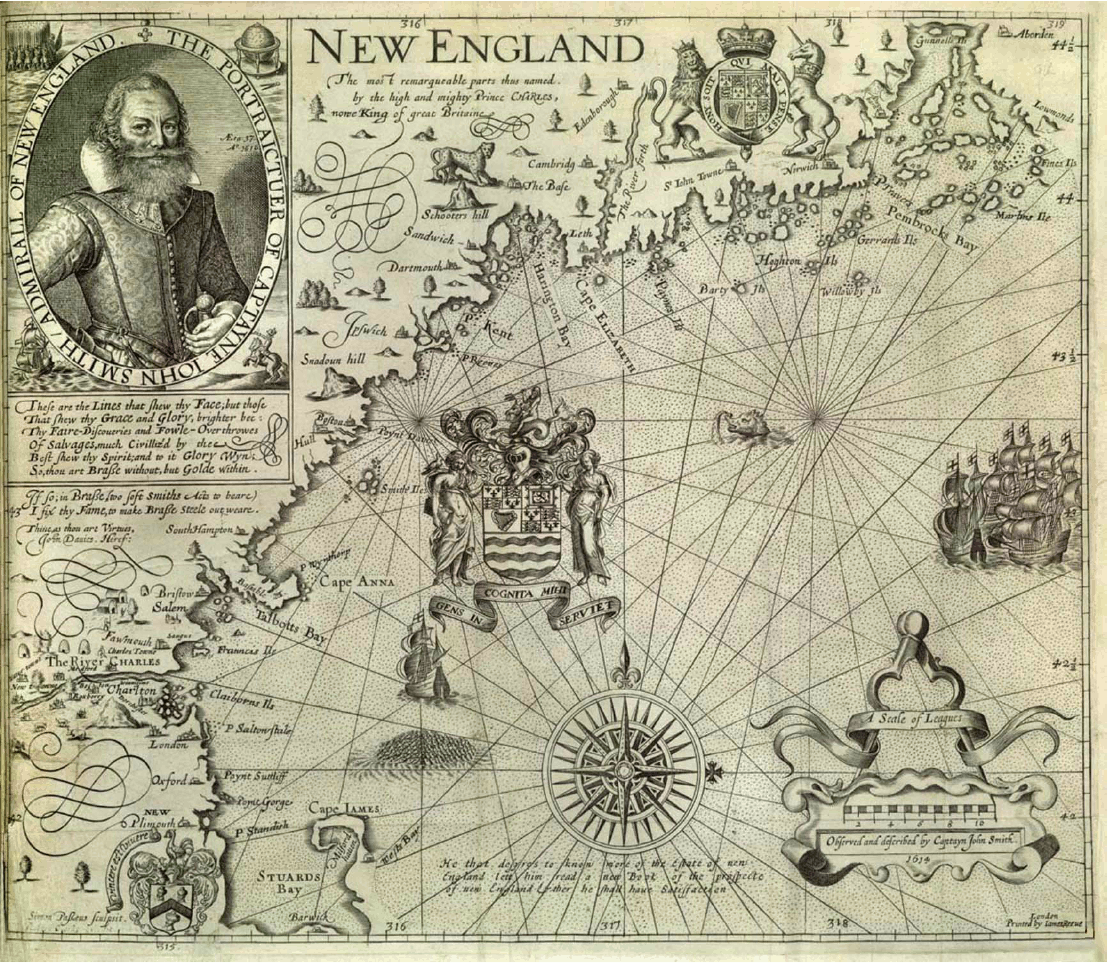

Map of New England by John Smith of Jamestown c.1616

The next time they made landing, they found the area to their liking with ‘streams of fresh water running to the sea. The soil promised well for their corn. The place was well wooded with oak, pine, walnut, beech, ash, cherry, plum trees and herbs of every sort abounded, as well as “Great Store of leek and onions”. There was also sand, gravel, and clay “excellent for pots”. The brooks “began to be full of fish.” With agreement from the Plymouth Company of Virginia that somewhere in this locality they could establish a settlement (but ignored the Wampanoag people living on the land already), they returned to the Mayflower with the excellent news. However, this was only the beginning of what would be a terribly hard winter for ‘The Pilgrims’. To begin with, William Bradford’s wife inexplicably was lost overboard whilst the party had been away.

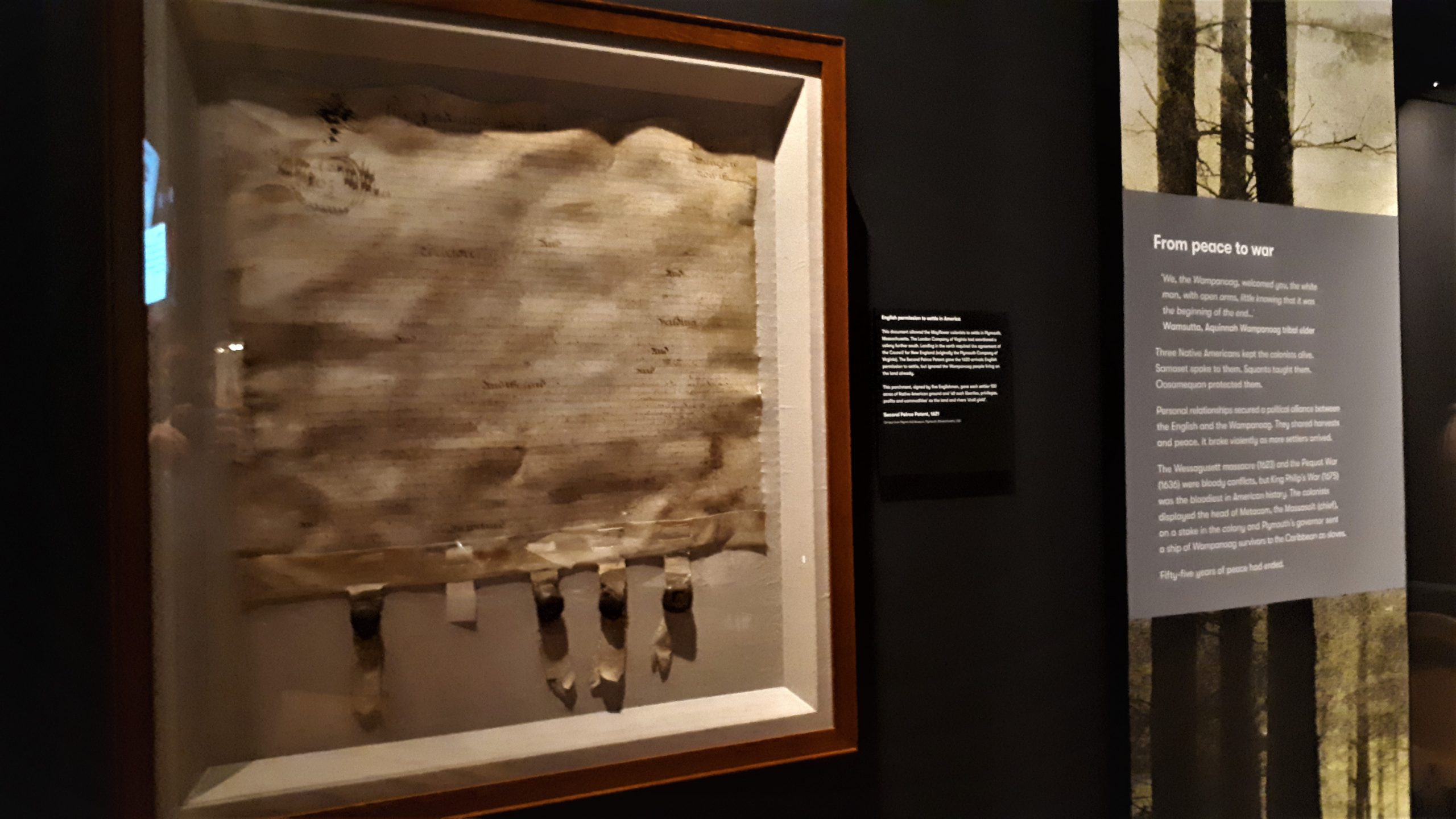

The Second Pierce Patent c.1621 – This document allowed ‘The Pilgrims’ to settle in New Plymouth, Massachusetts by the Plymouth Company of Virginia (later the Council of New England). It gave each settler 100 acres of native American ground and ‘all such liberties, privileges, profits and commodities’ as the land and rivers ‘shall yield’ © The Box, Plymouth

The majority of the Leiden community voted for a place that had been named “Thievish Harbour” by earlier visitors to the coast and became “New Plimoth”. With winter approaching ‘The Pilgrims’ faced the challenging task in the icy wind and rain of building living quarters and growing food in the ‘dripping trees and sodden earth’. All of the landing party were suffering from hacking coughs, the result of colds and the play of the wintry air on their bodies, weakened by the stresses of the voyage.

The winter of 1620-21 was so severe that nearly all the women among ‘The Pilgrims’ died, and many of the men too, as much as half of the company. Winslow is reported to have said “Some think it to be colder in Winter (than in England), but I cannot say out of experience so say”. Whilst Winslow, a man who appeared to have ‘tremendous energy and a tireless spirit” was making journeys of exploration with attempts to start trading stations with the Native Americans, his wife Elizabeth had died during that terrible winter. Susannah White, also heavily pregnant with child lost her husband. Due to the difficulties experienced, it was felt Susannah should have the protection of a man and so later married Edward.

First Contact with The Wampanoag

Massasoit statue looking out over Plymouth, MA © See Plymouth Massachusetts

‘The Pilgrims’ wished to make contact with the Native Americans but it was over three months after the settlement that they’, understandably fearful of the Englishman’s guns, had the courage to approach the plantation. The first to visit was Samoset, a Pemmaquid chief who spoke broken English. They gave Samoset food and drink who lodged for the night. He told them that, in general the Native Americans had not been favourably impressed by the arrival of white visitors to their shores. There had been killings. The Native Americans had been deceived and abducted into Slavery. Their attitude therefore ranged from one of Cautious reserve to downright hostility. He told them that New Plymouth was called Patuxet by the Native Americans and that following a great plague in 1617, nearly everyone had died, so the Pilgrims could take possession of this area.

Having stayed a few days, he later returned with beaver skins to barter and later brought the only surviving native of Patuxet, Squanto – a man who had been carried away captive by a ship’s captain called Hunt, and sold for £20.00. He had lived at Cornhill, London and could speak a little English. He was later bought by Spanish monks. They tried to convert him but ended up freeing him. Samoset promised the Pilgrims that he would introduce them to their nearest neighbours, the Wampanoags, a sub-tribe of the Pokanoket whose Sachem or Chief was called Massasoit.

The Wampanoag

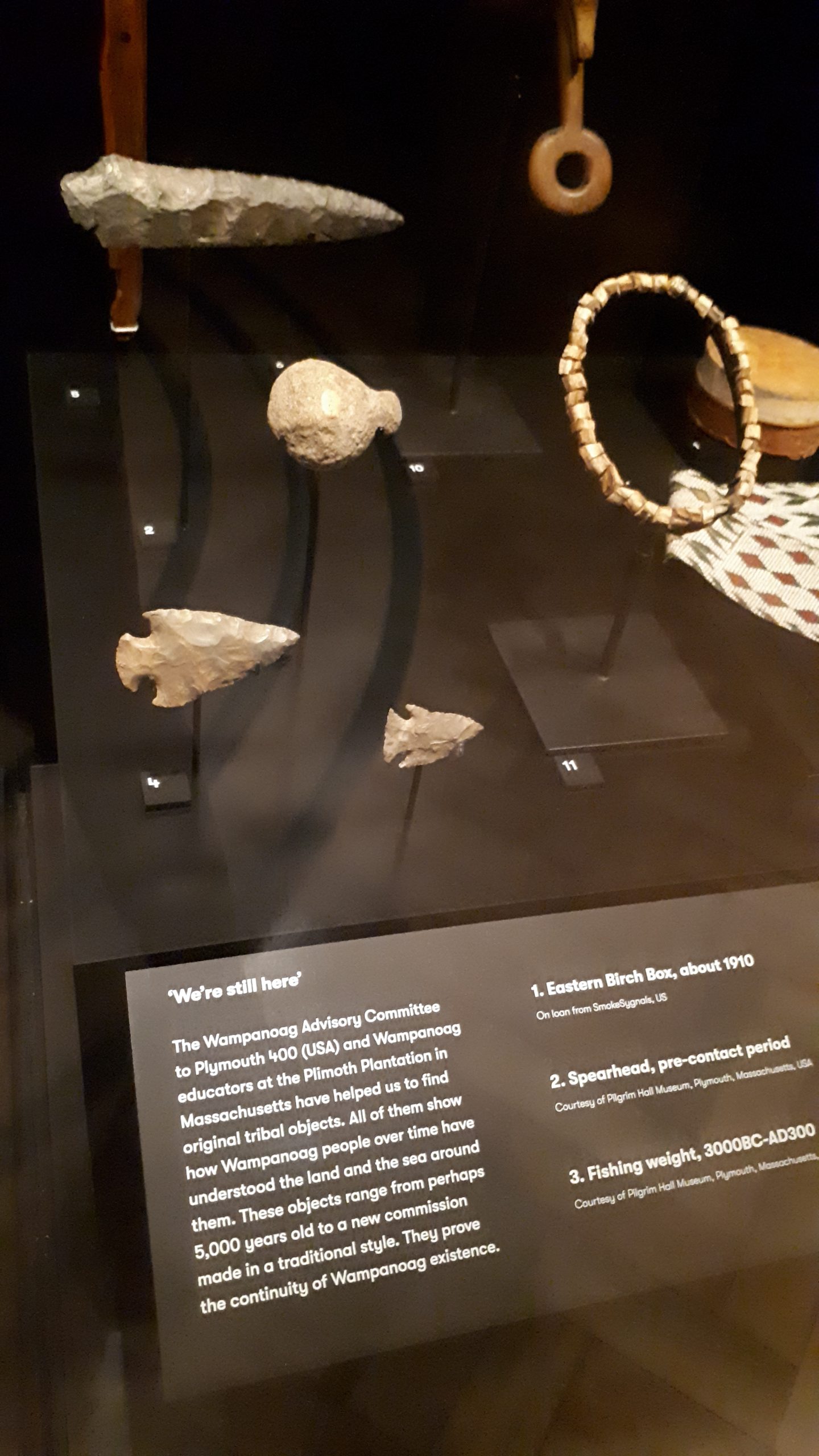

Examples of original Wampanoag tribal objects, some of which are as much as 5000 years old on display at Mayflower 400 at The Box, Plymouth. These included a fishing weight, spearhead, beaded sash and burden basket.

A cooking pot made by artist Ramona Peters and specially commissioned by The Wampanoag Advisory Committee & The Box, Plymouth for Mayflower 400 © The Box, Plymouth

Mayflower 400 highlights strongly the contribution of the Wampanoag people with artefacts and displays, along with a separate exhibition by a Wampanoag artist. It was, after all, Massasoit, leader of The Wampanoag whose actions, alongside Winslow’s proved to be the heart of the successful establishment of the colony at New Plymouth. Wampanoag means People of the First Light and prior to the early 17th century, the Wampanoag lived in 70 villages along the coast of modern-day Boston to Cape Cod and west into Central Massachusetts. However, the population was decimated between 1616 and 1619, nearly all dying from European diseases (Squanto’s great plague) which they had no immunity too. Those Wampanoag that were left, were, like the colonists, worryingly outnumbered (though by the nearby Narragansett people) and wary of Europeans.

The Wampanoag were an ancient and sophisticated people. They understood the rhythm of the seasons, land and the sea which had ensured their survival for thousands of years. They lived a self-sufficient hunter-gatherer lifestyle which endured, living in Wetus (houses) near the coast in Summer to take advantage of fresh seafood and in the Autumn moving inland to building new homes for protection from the weather and to fish and farm. They grew corn, squash and beans and the agriculture was managed by women, who passed farmland down the female line.

Examples of pottery on display at the Mayflower 400 exhibition that would have been used by the colonists © The Box, Plymouth

Amongst an example of a traditional Wampanoag Cooking Pot specially created for the exhibition in partnership with The Wampanoag Advisory Committee were a range of tribal objects, some of which are as much as 5000 years old. These included a fishing weight, spearhead, Beaded Sash and Burden Basket demonstrating their sophisticated relationship with and uses of the land and sea. Recent archaeological excavations at Burial Hill in the Plymouth Colony have found Wampanoag pottery and plates, alongside those wares traditionally used from England, changing our understanding of how these early settlers may have lived.

Exhibition display illustrating the Wampum bead drilling process © The Box, Plymouth

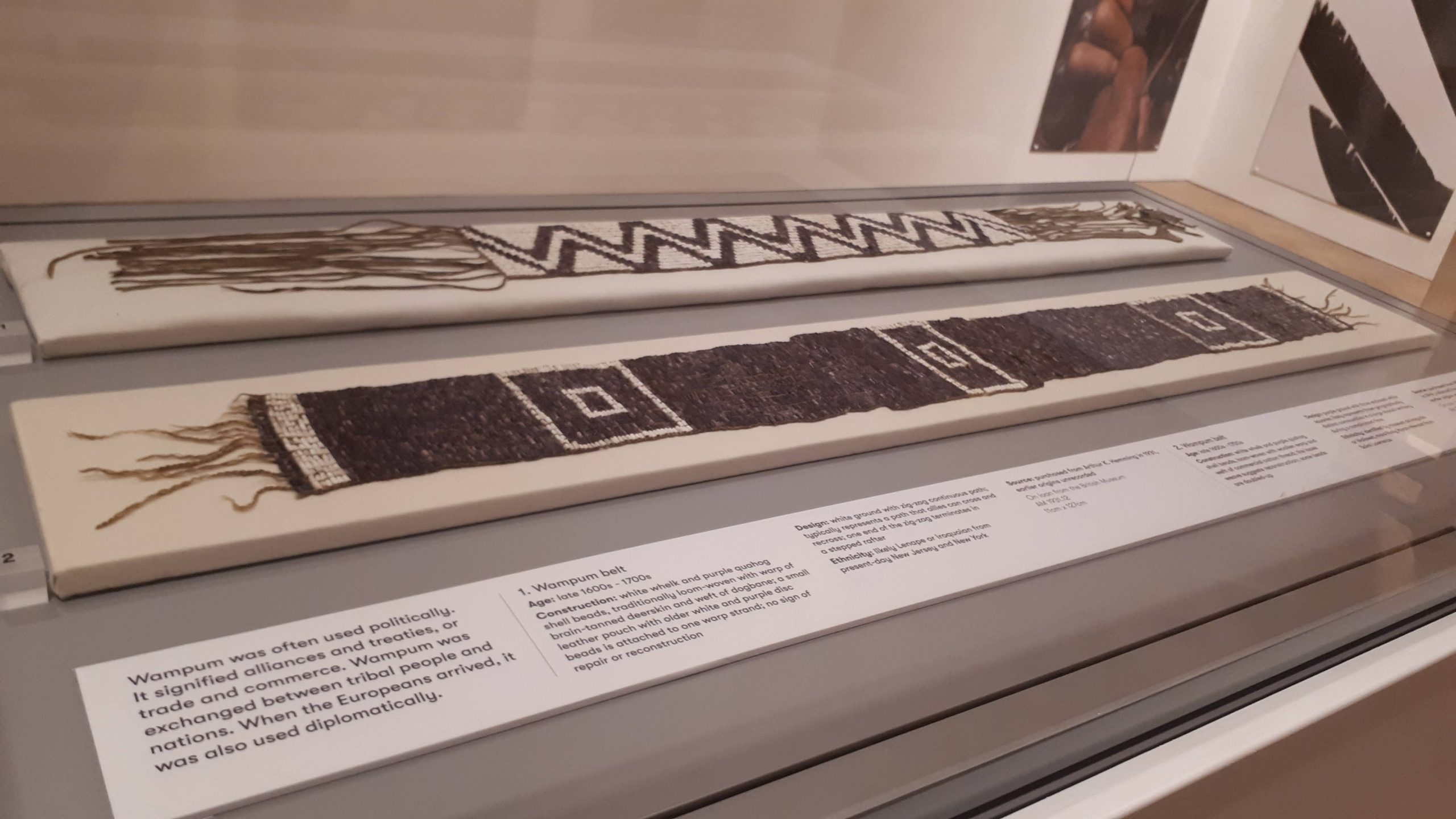

Whilst new discoveries have shed light on the relationship between the colonists and the Wampanoag, Wampum, a separate exhibition that can be viewed alongside Mayflower 400 at The Box offers incredible insight into the history, culture and importance of Wampum to the Wampanoag. Wampum are drilled beads which are used to create Wampum belts, these symbolise stories of peoples, places and are imbued with meaning and memory. Each belt is individual created with many beads which may represent a village, clan or sometimes an alliance. The beads themselves are skilfully crafted from drilled quahog and whelk shells, indigenous to the coastline. The exhibition highlights strongly that far from an archaic culture from the past, the Wampanoag are a living, breathing people in the 21st century.

Exhibition display of two Wampum belts © The Box, Plymouth

Edward Winslow, Massasoit and Watson’s Hill

The two Native Americans who had come as messengers returned to the Sachem and after an hour, the King came to the top of Watson’s Hill with 60 warriors. Both sides both cautiously kept their distance and Squanto parleyed with Massasoit, but to no avail. Massasoit would not come down from the hill and ‘The Pilgrims’ would not entrust their governor Carver to ‘the Salvages’. There was deadlock.

It was at this point that Edward Winslow’s actions have been celebrated ever since. Edward went up the hill to parley and ensure he knew the Governor’s will and mind, which was to have trading and peace with him. He collected a copper chain with a jewel set in it and two knives as gifts. He also took a knife and jewel for the King’s brother known as Quadequina along with a pot of ‘strong water’ (spirits), biscuit and butter. Winslow in armour and carrying a sword approached Massasoit and gave a speech ‘with words of love and peace and that King James did accept him as his friend and ally’ and that Carver desired peace with him as his nearest neighbour. Massasoit enjoyed the speech and they ate and drank together, and he gave some to the rest of his men.

After some discussion, the Chief was so well assured that he left Winslow in charge of Quadequina and with twenty Native Americans went to the Governor, leaving weapons behind them. After salutations the Governor kissed the Chief’s hand and Massasoit returned the kiss. Following a great draught of ‘strong water’, a Treaty of Peace, Alliance and Mutual Defence as drawn up. The outcome of these negotiations was significant as Massasoit held the status of paramount Chief in the region of the ‘New England States’. His example of concluding a treaty of friendship to regulate relations between his people and the Pilgrims was later followed by nine other tribal leaders.

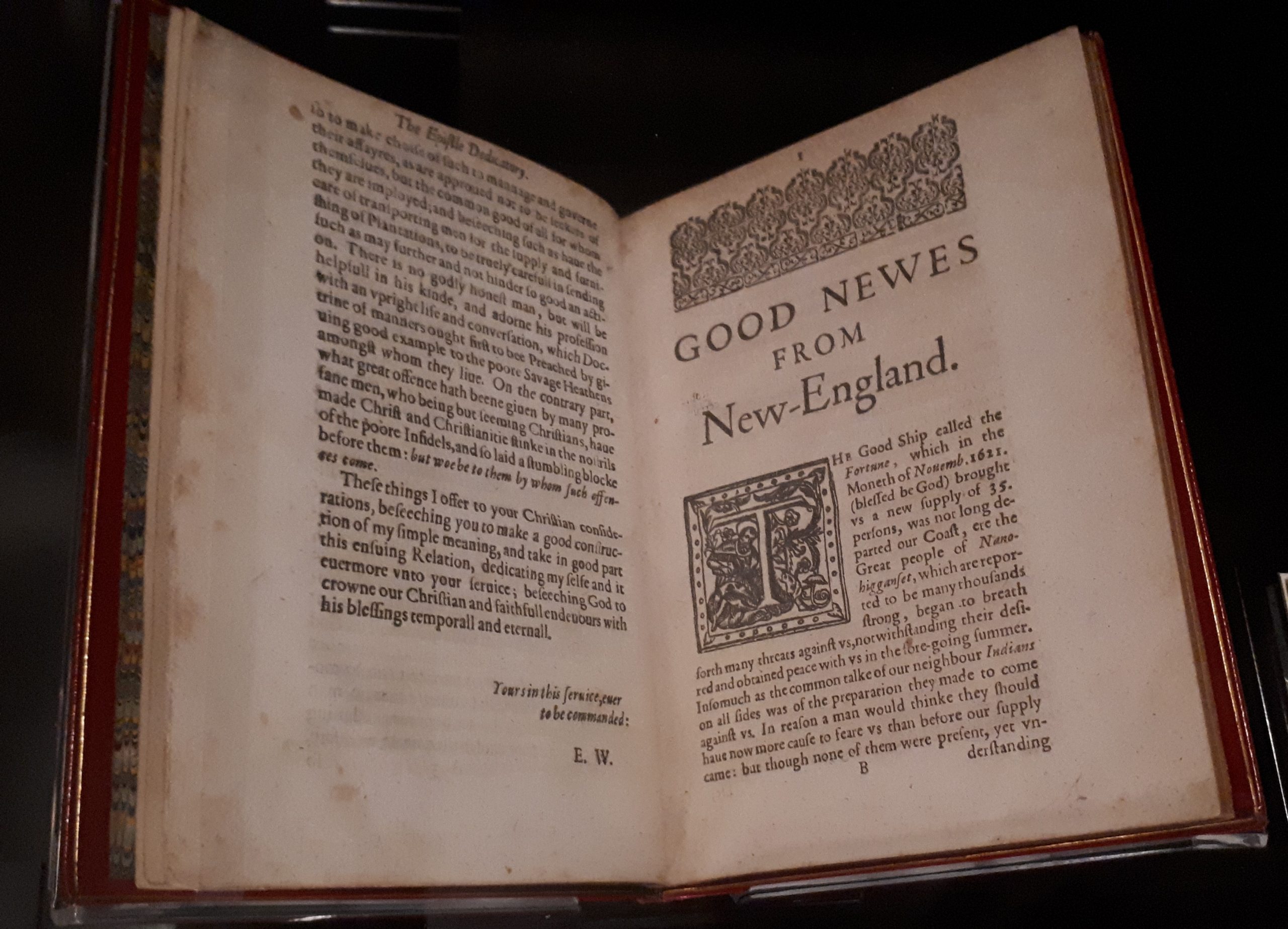

Edward Winslow’s Good Newes from New-England on display in Mayflower 400 at The Box, Plymouth © The Box, Plymouth

Little did Edward Winslow realise at the time, but his careful actions during that day would seal a lifetime of friendship between him and Massasoit and took the first essential step to securing peace that would preserve the New England colony for fifty years without serious troubles. Edward would go on to save the life of Massasoit of a deadly sickness, tending him for two days, with quite miraculous results and was reported in his Good Newes from New England. This sealed the loyalty and friendship of the Chief and his people for the lifetime of the King. With Mayflower acting as a deterrent all winter, she left for England on April 5th 1621, carrying mail home for the Pilgrims. In the Autumn, a sail was sighted on the horizon which turned out to be a brig called Fortune who carried 35 new recruits for the colony, including Edward and Gilbert Winslow’s brother John.

John Winslow reported that the Winslow’s were flourishing in Draycott, Kempsey. Edward’s father Edward Senior had retired to the hamlet of Clifton. Kenelm came out in 1634, and his brother Josias a year later. Gilbert was the only brother who did not stay in New England returning home in 1646.

Edward Winslow and Massachusetts

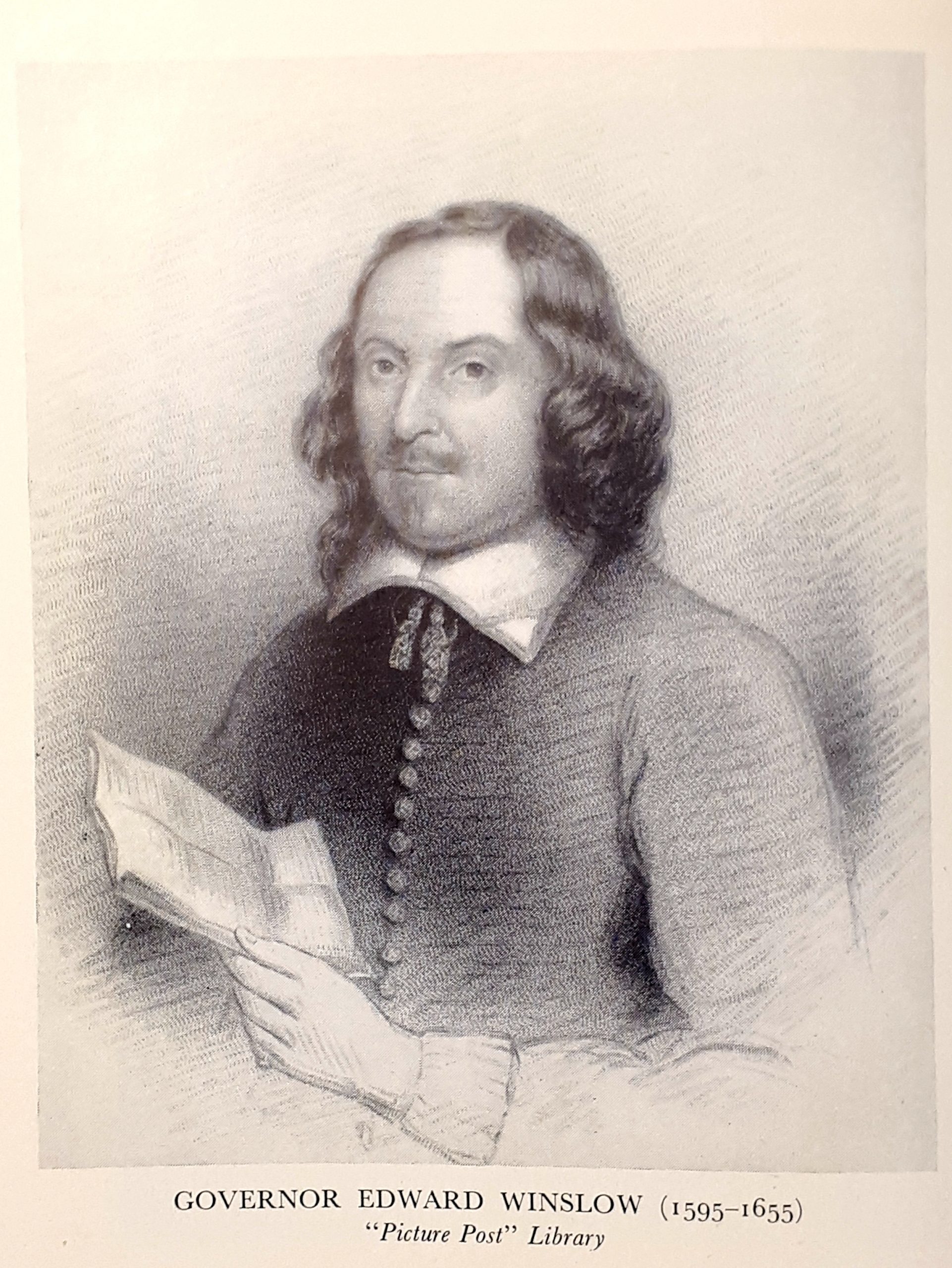

Governor Edward Winslow (1595-1655) ‘Picture Post’ Library in © D. Kenelm Winslow, 1957

By 1635, Edward had already been Governor and Assistant Governor of the Colony and had twice visited England to placate the Merchant Venturers who had put up the money for the Plymouth project. He managed to negotiate the release of the ‘New Plymouth’ settlement of their agreement which hadn’t worked well. By his third visit in 1635 to England to act as ‘Ambassador’ of Massachusetts, the Colony to the north of New Plymouth (following an enquiry by a newly created Commission investigating Colonial matters), it was clear that England was on the brink of revolution under King Charles I and the King was unhappy about the measure of autonomy that the colonies held. Winslow ably refuted the criticisms made regarding Massachusetts at the time, such as arguing that it was impossible to wait several months ‘for permission’ to take the requisite action against hostile or foreign interference.

Edward returned to New England in 1635 and in 1644 was once again elected as Governor. However, with Massachusetts once again in trouble, he returned to London once again. Saying farewell to his wife Susannah and children, Edward thought he would only be away a few months. He would never return to New England, being buried at sea as a Commissioner under Cromwell on his way to Jamaica on 9th May 1655. Whilst Edward himself never returned, his descendants and those of the other Winslow brothers of Worcestershire flourished in New England.

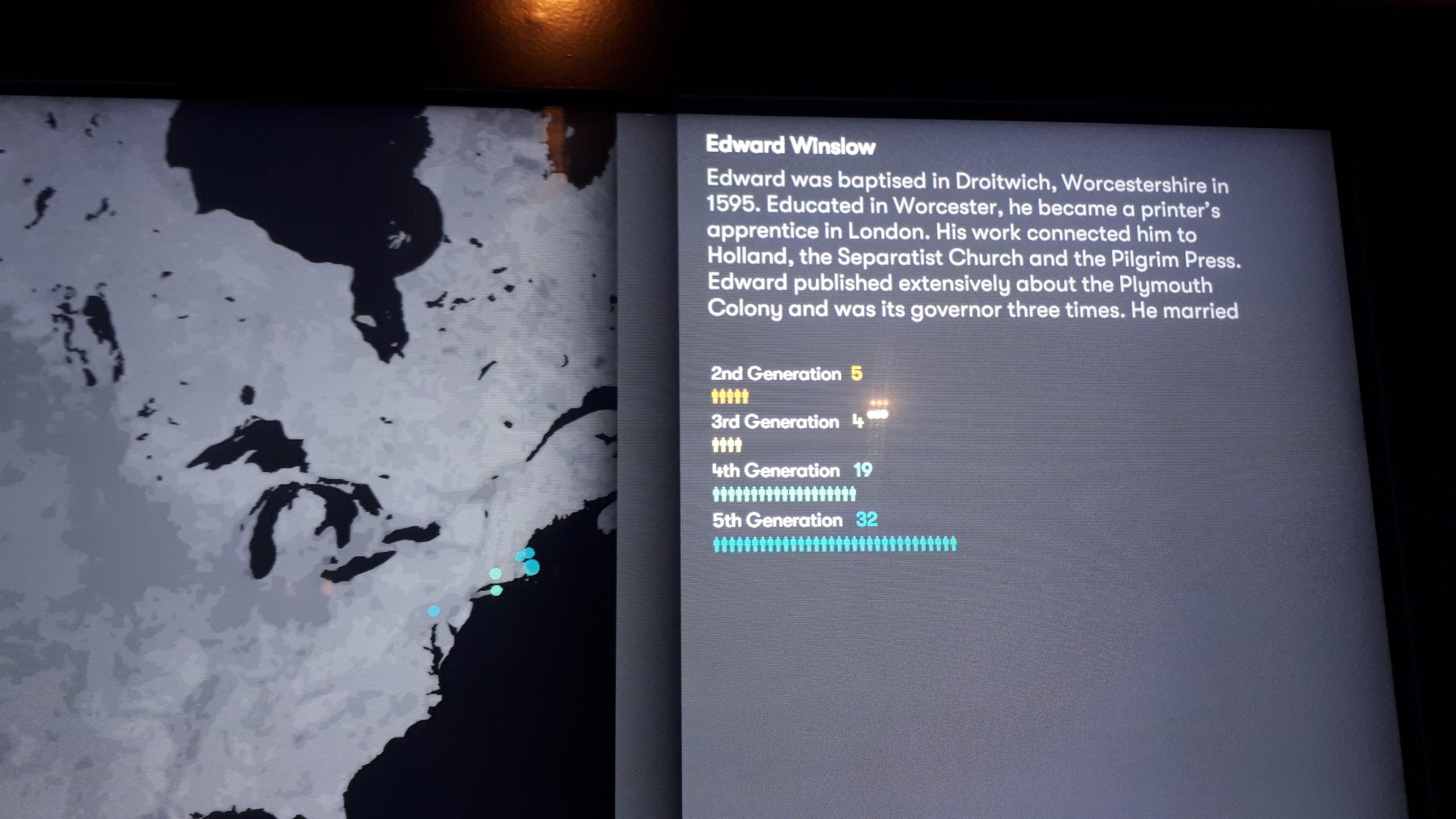

Edward Winslow’s descendants shown geographically in Mayflower 400 at The Box, Plymouth © The Box, Plymouth

The General Society of Mayflower Descendants, estimates that there could be as many as “35 million Mayflower descendants in the world” (though recent research has suggested the figure is likely nearer 3 million). Due to the partnership with the New England Historical Genealogical Society, the Mayflower 400 Exhibition at The Box, Plymouth presents the images of 1,000 Mayflower descendants of today. A brilliant computerised feature enables a visitor to highlight a particular colonist e.g. Edward Winslow and trace geographically, their descendants in New England today.

An image of some of the New England descendants of Mayflower shown in Mayflower 400 at The Box © The Box, Plymouth

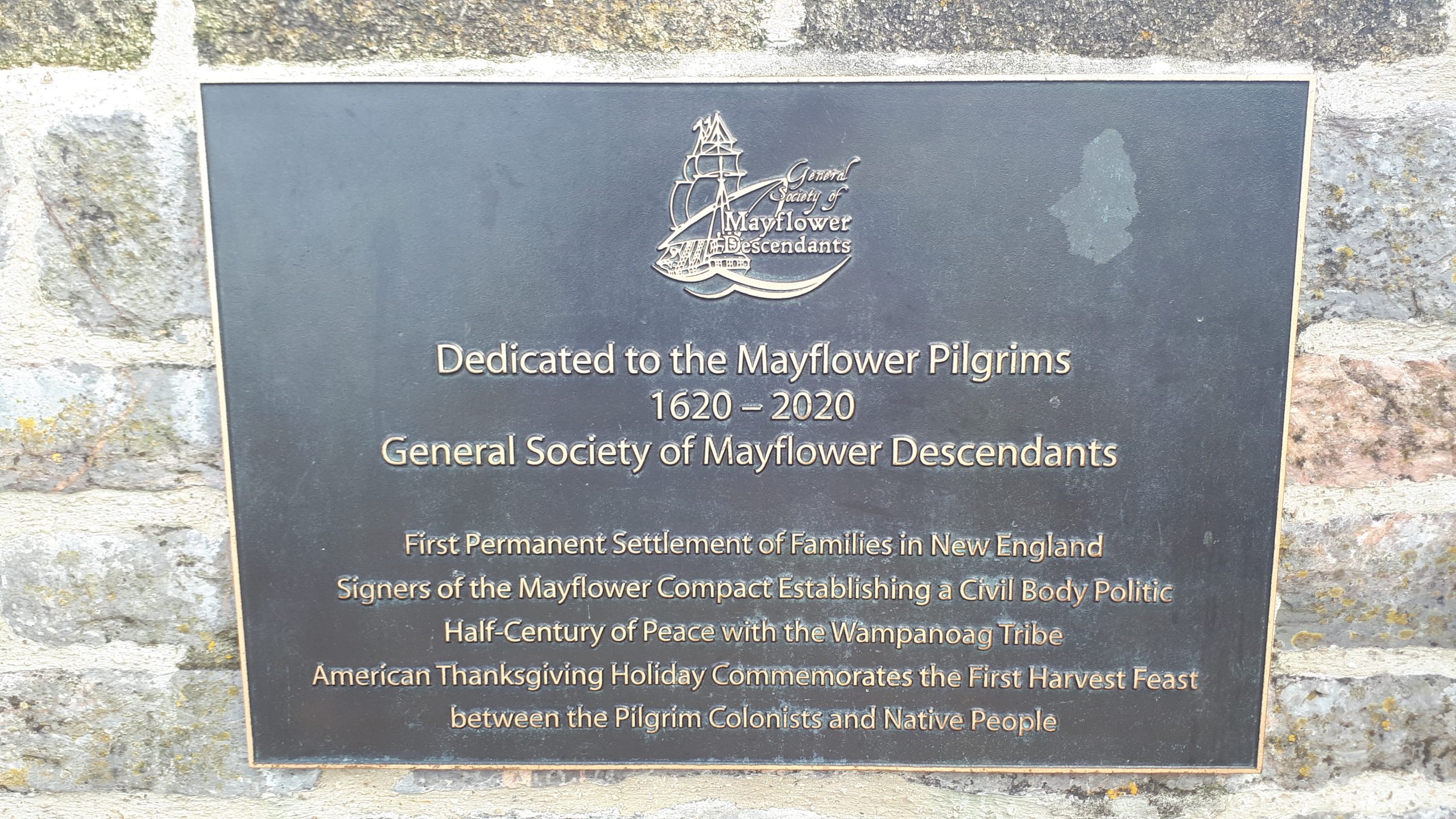

When I last visited Plymouth a few weeks ago, I once again walked The Mayflower Steps. This time I caught sight of a new plaque that had been placed to commemorate the 400th Anniversary of the establishment of the first permanent settlement in New England, the significant step of The Mayflower ‘Compact’ signed, prior to landing which created a ‘Civil Body Politic’ and the half-century of peace that existed between the colonists and the Wampanoag tribe. As an adult, I now understand more fully the hardships and challenges faced by the colonists and the Wampanoag. Most importantly Mayflower 400 restores and celebrates the central role of the Wampanoag as part of the cultural identity of New England, along with the legacy of Mayflower.

A plaque installed by the General Society of Mayflower Descendants at The Mayflower Steps, Plymouth for the 400th Anniversary

**Please note, all images shown of Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy Exhibition are the copyright of The Box, Plymouth.

Further Information: Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy

Books:

- Kenelm Winslow, Mayflower Heritage (1957)

- Sterry Cooper, Edward Winslow of the “Mayflower” (1953)

George G. Wolkins, Edward Winslow, King’s Scholar and Printer (1951)

All available at The Hive, Level 2: Local Studies – L 929.2 WIN

Very Interesting Paul, thank you for sharing.

Extremely informative and interesting