An Eighteenth-Century Ghost Story

- 30th October 2021

Thomas Lyttelton, 2nd Baron Lyttelton by Richard Brompton. Used under Creative Commons

Within the Lyttelton Archive, which came here after being given to the nation, and which is being catalogued, is an intriguing story. There’s a story that Thomas, Lord Lyttelton, saw an apparition which foretold his death. The story has been told over the years and elaborated upon, but Maggie, one of our archivists, found an account written just the following year.

Thomas, Lord Lyttelton (1744-1779) lived a short but colourful life. However it’s the circumstances of his death that have continued to fascinate. The story included many elements akin to a gothic novel, an interesting thought given that Sir Horace Walpole, author of Castle of Otranto and contemporary of Thomas’s father, was one of many who have commented on Lord Lyttelton’s demise. Various versions of the curious events of November 1779 have been told and retold over the years. The Lyttelton archives here at the Hive contain their own near contemporary accounts and this blogpost seeks to use these archives to retell this mysterious story.

A woman in white gives a warning

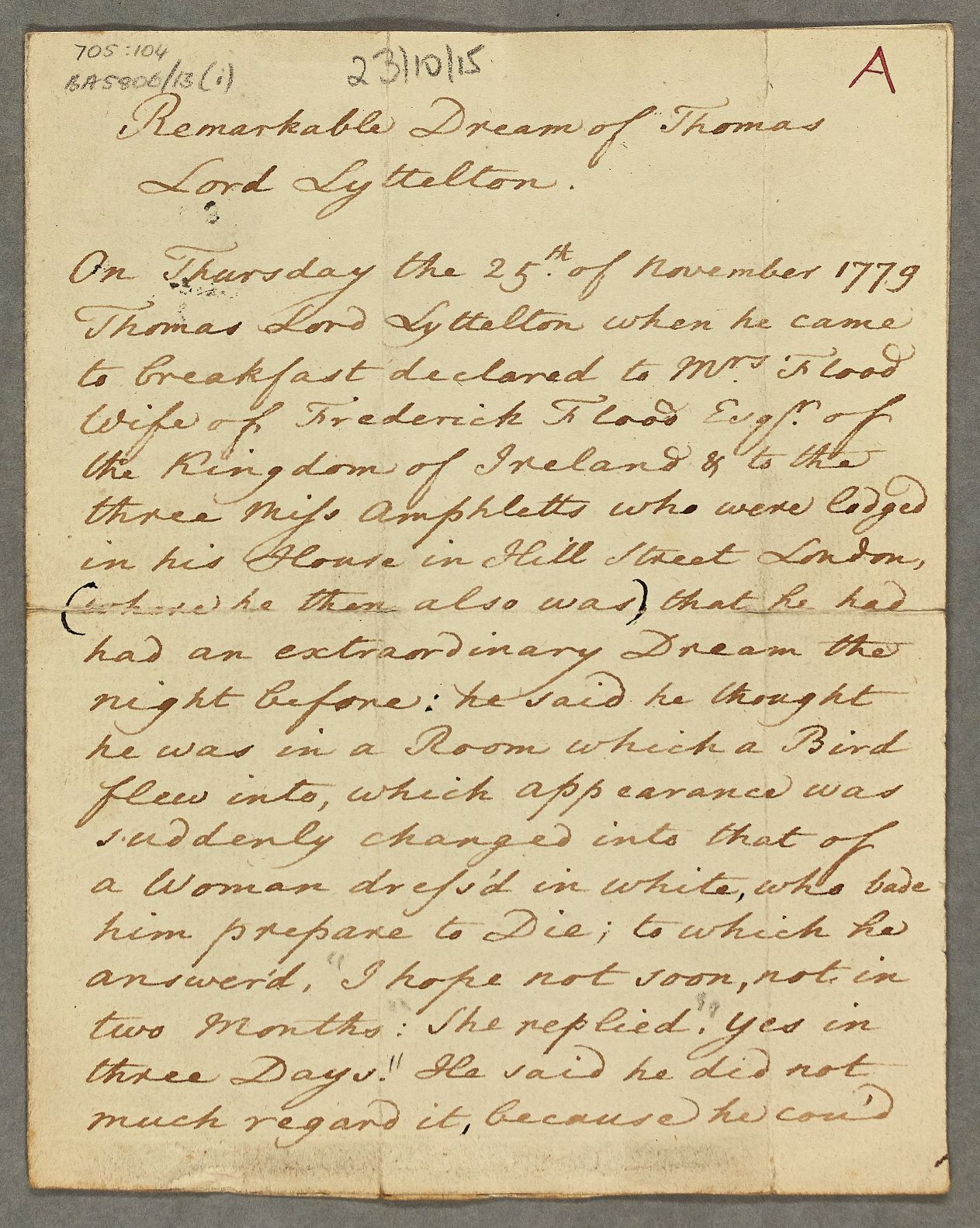

According to an account entitled ‘Remarkable Dream of Thomas Lord Lyttelton’ written by Lord Westcote our ghostly tale started on the morning of Thursday 25 November 1779 at Lord Lyttelton’s house in Hill Street, London. At breakfast Lord Lyttelton recounted to his companions the extraordinary dream he’d had the night before. He had dreamed that a bird flew into his room. It suddenly changed into a woman in white who told him to prepare to die. He said that he hoped that would not be too soon. The woman replied ‘Yes in three days’.

Lord Lyttelton said he did not put much store by the story as he felt it might have been influenced by the fact he had been with Mrs Dawson a few days before when a robin flew into her room. Over the next two days he made some speeches in the House of Lords and told the story to others. It became the talk of the town, even more so as events unfolded. Lord Lyttelton appeared to be in good spirits, stating that he did not look as if he was likely to die.

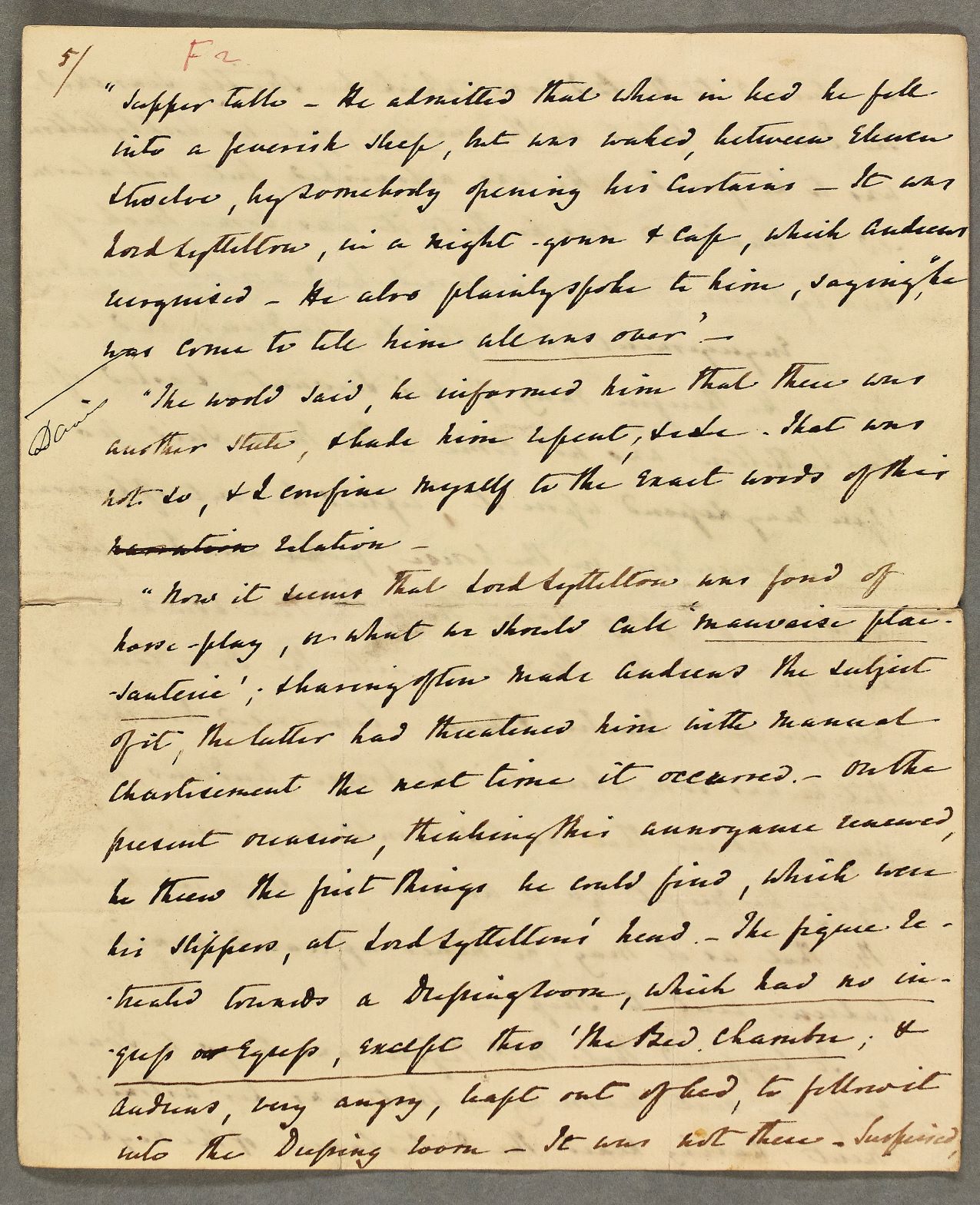

Page from Lord Westcote’s account describing the visit of the woman in white

Events at Pitt Place

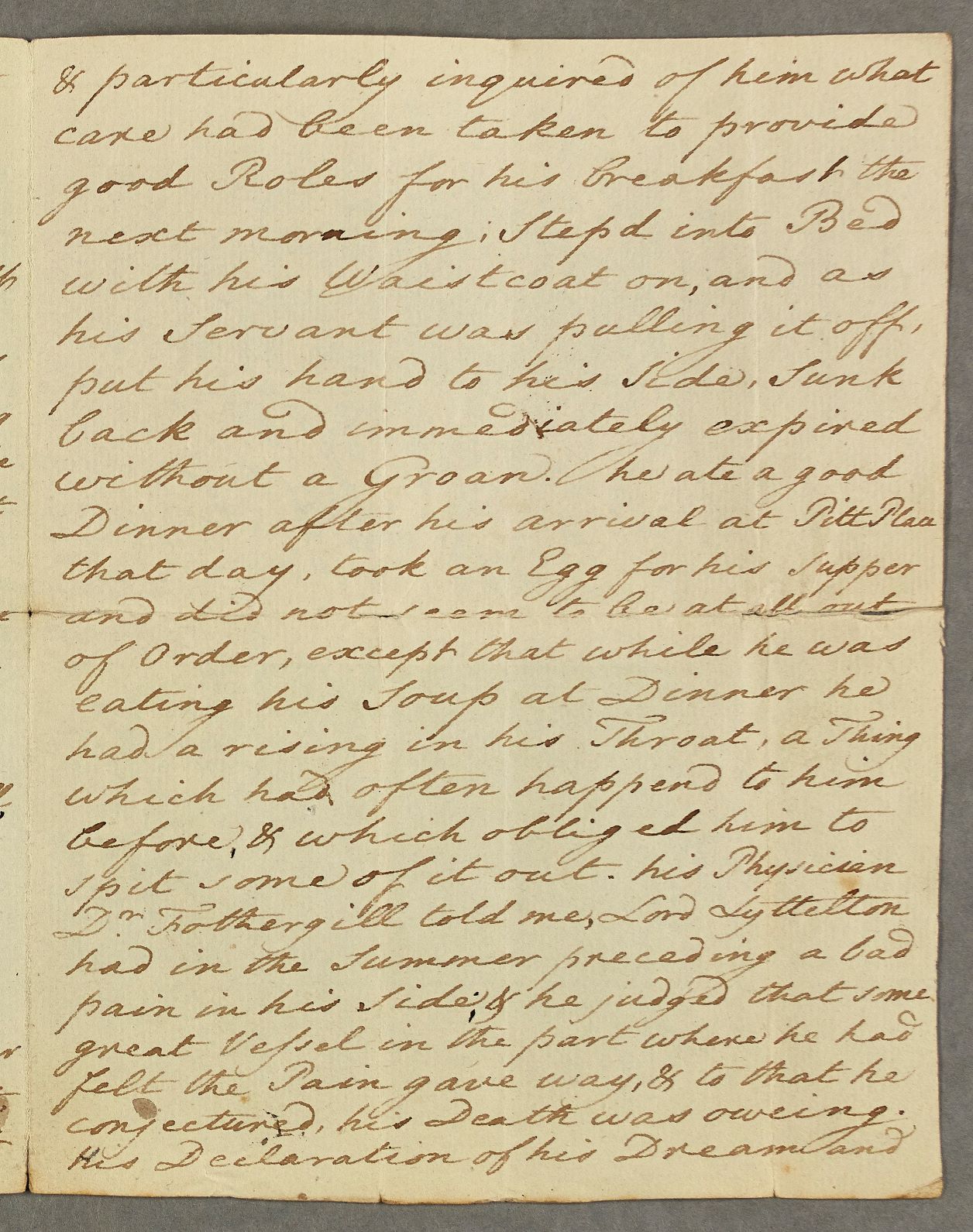

On morning of the third day after the dream Saturday 27 November Lord Lyttelton told his companions he was very well and believed he could ‘bilk the Ghost’ ie outfox her. Later that day he drove down to his country house, Pitt Place, Epsom with some friends where he dined and passed the evening in apparent good health, though Westcote’s version talks of him having had ‘a rising in his throat which had often happened to him before’. Upon retiring to bed soon after eleven o’clock, he talked cheerfully with his servant and in particular about provisions for the next day’s breakfast. Just as his servant was assisting him with his waistcoat, Lord Lyttelton put his hand to his side, sunk back and died on the third day, just as the woman in white had predicted.

Page from Lord Westcote’s account describing Lord Lyttelton’s demise

Pitt Place, Epsom, the house of Mr. Digby Neave, watercolour. Victoria & Albert Museum. Used under Creative Commons.

Mr Russel the music master’s tale

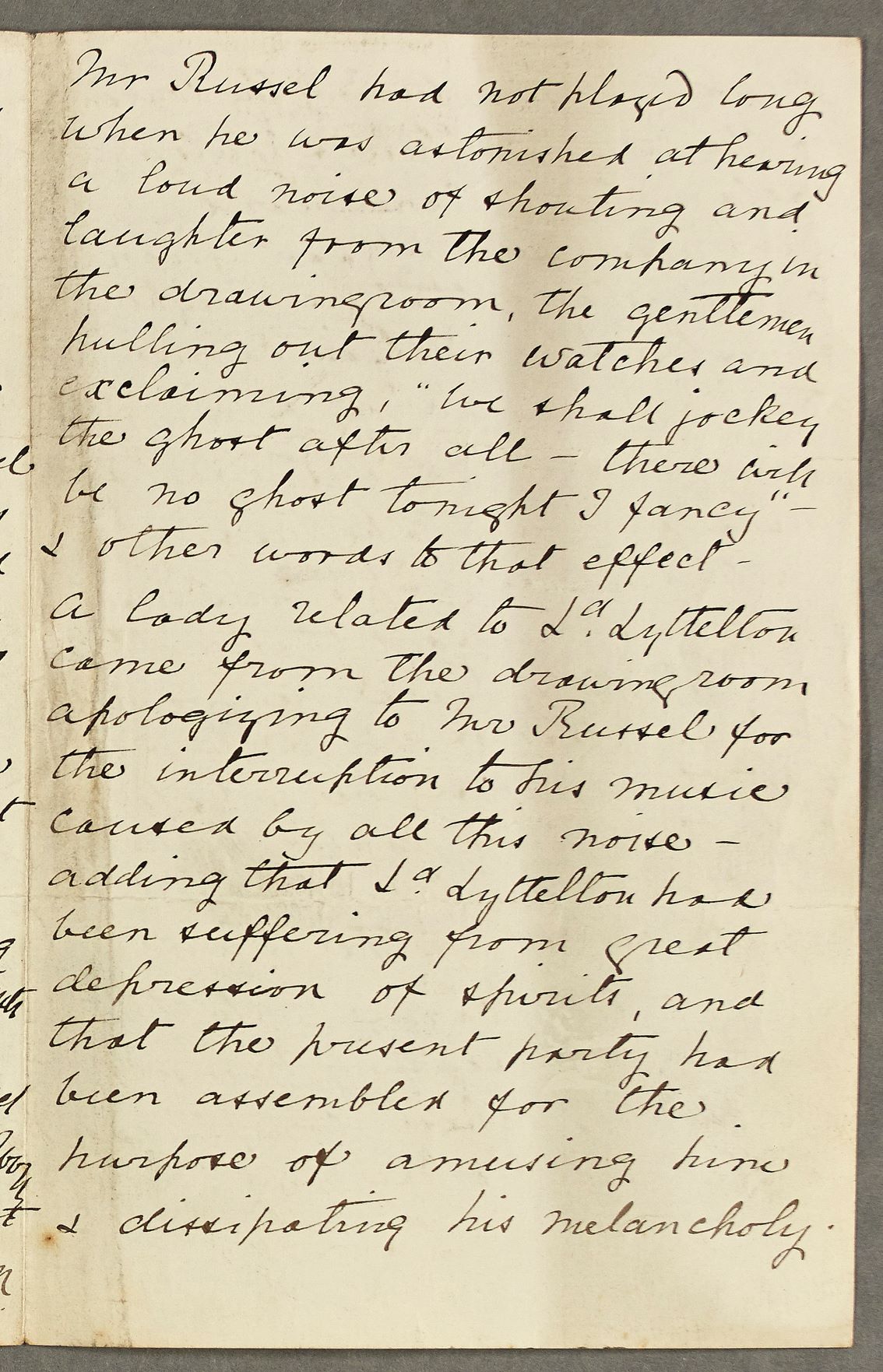

The Lyttelton archives also contain a slightly different version of the events at Pitt Place. Mr Russel, a music master, occasionally played pianoforte for Lord Lyttelton at his place in Epsom. On this particular occasion he recalled he played to a large party of people. As he was playing he was astonished to hear shouting and laughter from the drawing room as various people pulled out their watches and exclaimed variously ‘We shall jockey the ghost after all – there will be no ghost after all – there will be no ghost tonight I fancy.’ Another member of the company apologised for the interruption and explained the party was to amuse Lord Lyttelton and dissipate his melancholy.

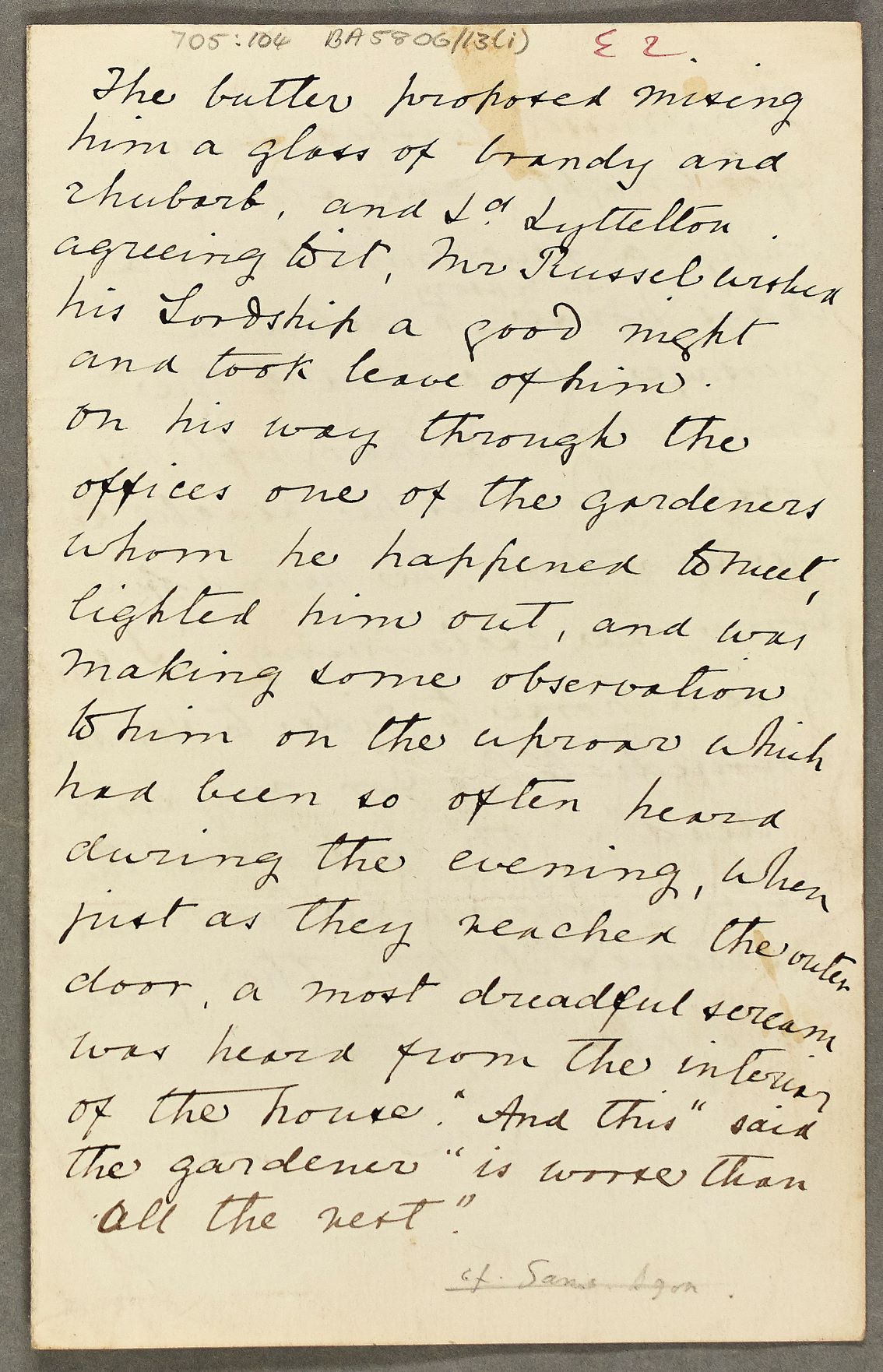

After he had finished playing Lord Lyttelton invited Mr Russel to join them for supper, but Mr Russel said he’d just take a glass of wine in the butler’s pantry on his way out. Lord Lyttelton came into the pantry, sat on the plate chest and complained to the butler he was feeling unwell and in pain. The butler proposed mixing up a glass of brandy and rhubarb. Mr Russel took his leave and as the gardener was lighting him out, a dreadful scream was heard. As he collected his horse from the local inn, Mr Russel encountered the gardener again who informed him that Lord Lyttelton had fallen off the plate chest speechless and died as he was being carried upstairs.

Pages from Mr Russel’s account of the evening at Pitt Place

Lord Lyttelton’s ghost?

A sequel to the story is given in an ‘Account of Lord Lyttelton’s appearance to Mr Miles Peter Andrews’ also to be found amongst the Lyttelton archives.

Mr Andrews, a close friend of Lord Lyttelton, had a place at Dartford where he was also entertaining friends and was expecting a visit from Lord Lyttelton over the weekend. On that same Saturday night Mr Andrews retired early to bed and fell into a feverish sleep. He was awoken when the curtains at the foot of the bed were drawn open to reveal his friend. At first he thought Lord Lyttelton had arrived after everyone else had retired to bed and asked his friend if he was playing some kind of practical joke, which he was well known for. The figure replied ‘It’s all over with me Andrews’. When Andrews got out of bed he could find no one in the room which was locked from the inside and a search failed to reveal Lord Lyttelton. Still convinced it was a trick of some kind, he ordered that no bed be offered to Lord Lyttelton. Instead he should spend the night in an inn or the stables.

The next morning one of the guests of Mr Andrews travelled up to London and was astonished to hear Lord Lyttelton had died the night he was supposed to have been seen at the house in Dartford. She sent a message to Mr Andrews who was so shocked that he ‘was not his own man again for three years’.

Page from Mr Andrews’ account of his encounter with Lord Lyttelton

Lord Westcote’s opinion

Lord Westcote (Lord Lyttelton’s uncle) was told by Dr Fothergill, Lord Lyttelton’s physician, that he judged death was due to a vessel in the gut having given way, Lord Lyttelton having previously had some bad pain in his side. Certainly other accounts make reference to Lord Lyttelton’s ill health, headaches, fits and chronic indigestion which required various medicines and bedrest. As for the dream and other events Lord Westcote stated he had made ‘close inquiry’ of various people present at them and they were asserted to him to have been so.

Acknowledgements

Images of documents from the Lyttelton archives with kind permission of Lord Cobham.

Sources

For further information about Lord Lyttelton see The Life of Thomas Lord Lyttelton by Thomas Frost 1876 and Thomas Lord Lyttelton Portrait of a Rake by Reginald Blunt 1936

For an account of the history of Pitt Place see PittPlaceFULLVer3.pdf (eehe.org.uk)

Other websites such as First Impressions of England and its People (electricscotland.com) and November 27th (thebookofdays.com) give other versions of the story.

Post a Comment