The Diary of Eliza Jane Molineux

- 27th October 2021

The diary of a Victorian lady, discovered behind a cupboard in Bradford before being passed to us, was one of the first items to be catalogued by our new Trainee Archivist, Tom Poole. He wrote this blog to share about the diary, what we know about it, and what is still a mystery.

As the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service’s new Trainee Archivist, I was eager to get started with one of an archivist’s principal duties – the cataloguing of accessioned records. I thought I would share some of my experiences after cataloguing my first series. Along with learning the techniques and methodology of description and hierarchy, I learned even more how easy it is to become fascinated with any one item in particular, to want to uncover the story behind who created it, and how it came to end up in the archive’s hands.

My first item, then, was something which had slid across The Hive’s desk only a few years ago. The personal diary of an Eliza Jane Molineux; a hefty leatherbound book, beautifully preserved for a volume which is, at the very least, 160 years old.

Initially found stashed behind a cupboard in Bradford, Eliza’s diary covers entries ranging between 1st January, 1861, and 25th October, 1864. Whilst not exclusively, the volume’s content is mostly kept to the topic of travel; densely packed with recollections of an incredible array of trips across the UK, France, and Belgium. It provides a window into the daily life of the Victorian woman whose hand it is written in. Not only is the book incredibly well preserved, but Eliza’s diary is written in remarkably legible handwriting, in excellent English, and signposted clearly by her consistent use of dates in the margin, making her journal a brilliantly accessible piece of history.

How it ended up in Bradford is not clear, predominantly due to the fact that its author, Eliza, lived in Kempsey, here in Worcestershire. Whilst it had been discovered by relatives of the eventual depositors all the way back in the 1940s, it was Molineux’s locality to this county that led our depositors to donate the diary to us – closer to where its author had spent so much of her life. They had even taken the care to deposit with the book a dossier of their own research, including some photos of relevant locations that they thought might be of interest.

About the diary

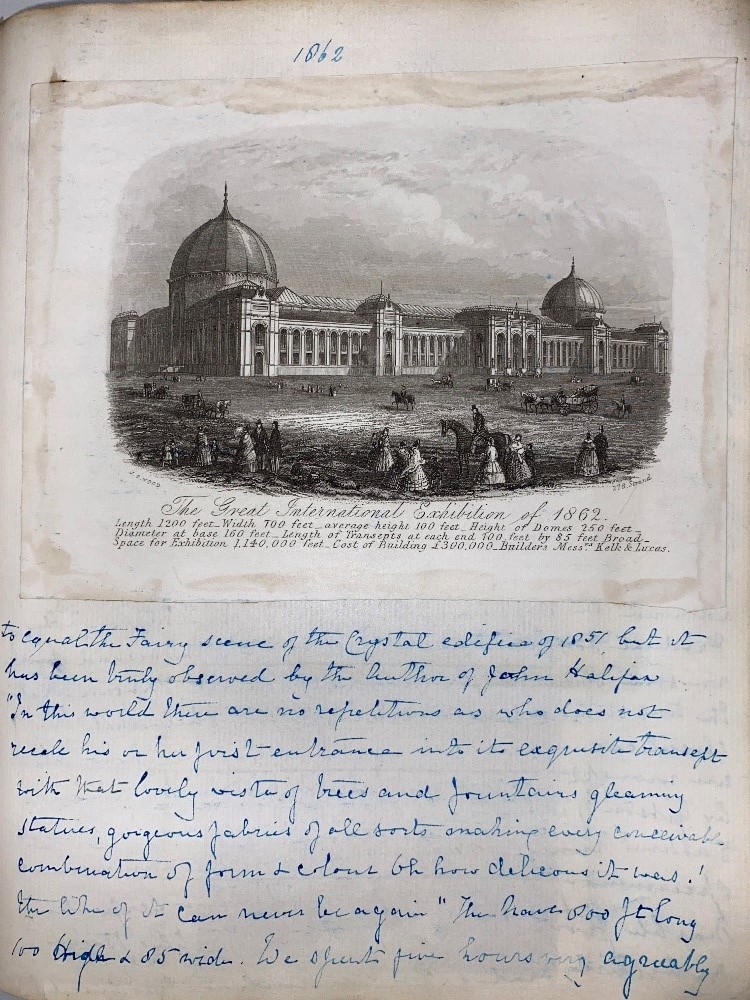

Eliza describes events which uniquely date the pages within time – such as her visiting to the Crystal Palace on a number of occasions, or her visit to The Great International Exhibition of 1862.

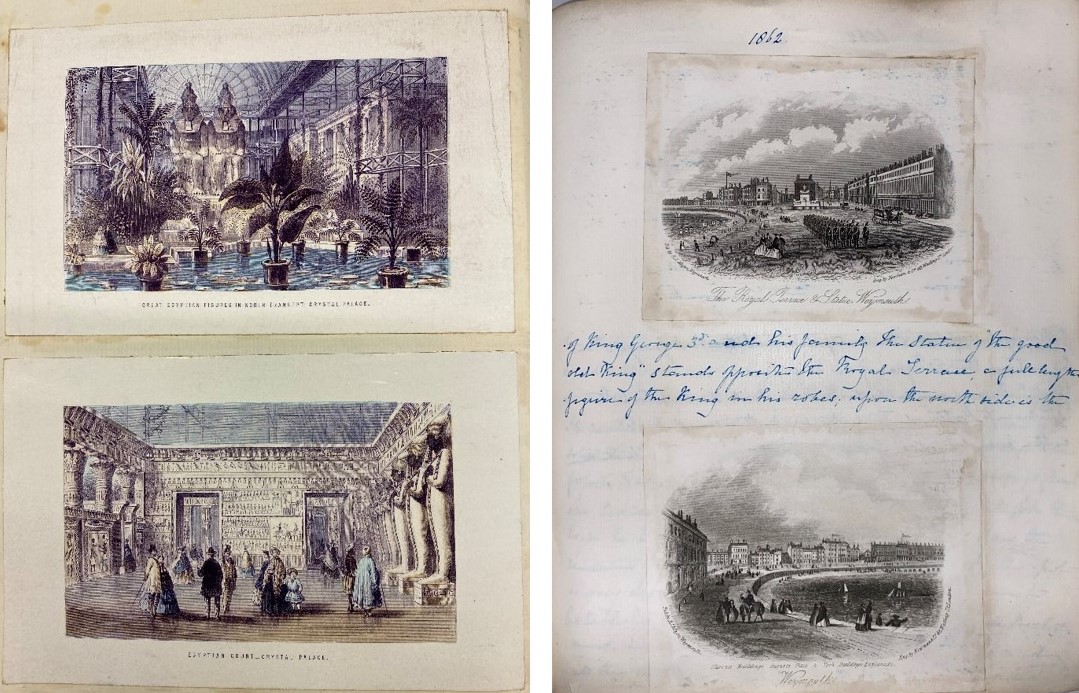

And, as most pages are considerately illustrated with contemporary prints, both in black and white and in colour, the reader is often provided with a rich sense of vision as to what Eliza could see.

Two coloured prints depicting rooms of The Crystal Palace, 1862; Two prints depicting Weymouth, 1862

Molineux’s journal contains little direct evidence to suggest that this was a volume ever intended for public view. Yet, her stylism was very much in keeping with the popular nineteenth century trend of travel writing, a genre pioneered and populated by the likes of Maria Graham or Mary Kingsley. Whilst this is only a speculatory conclusion, it would not be unwarranted to believe this item to be at least in keeping with that trend, if not directly inspired by it.

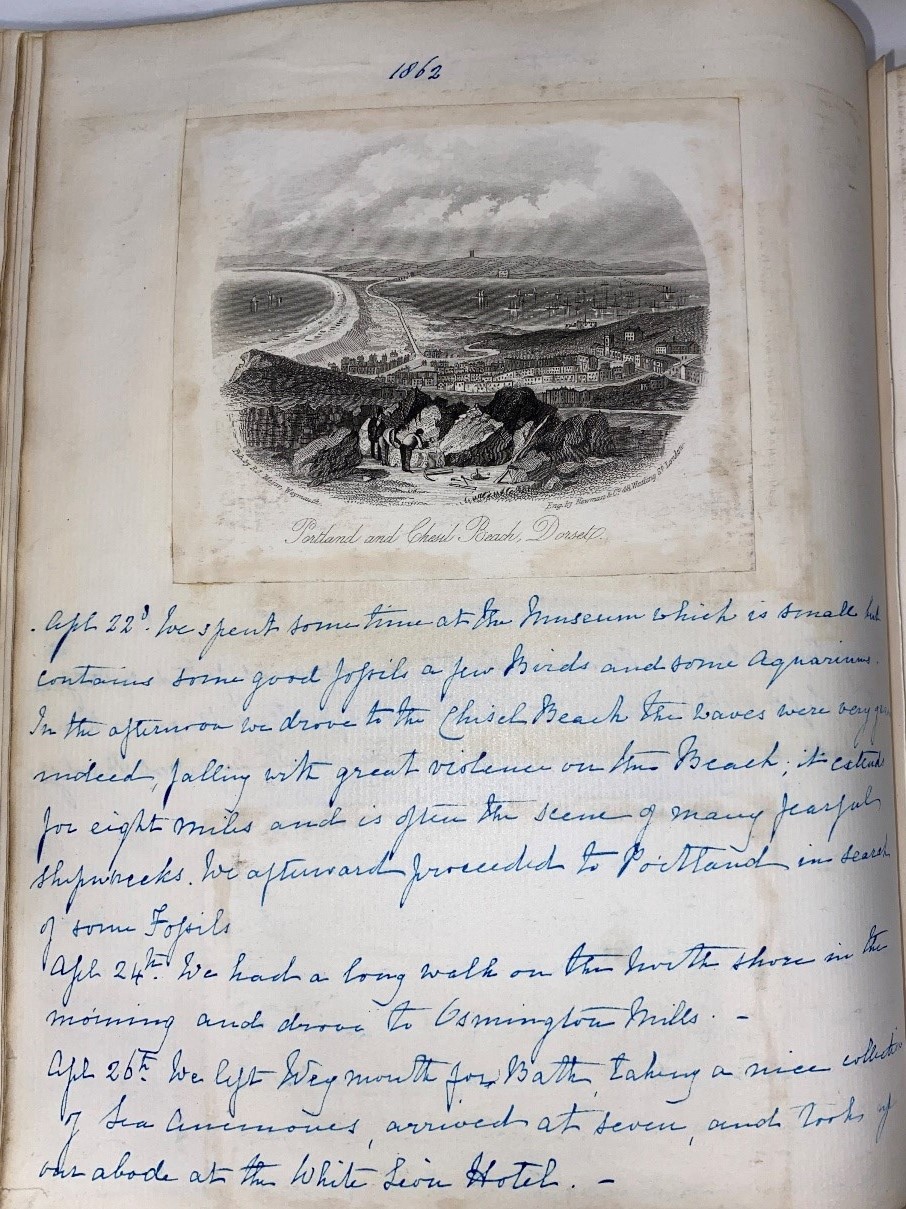

Certainly, her journal is laden with waxing prose and extended poeticisms. So enamoured by her visit to Bath Abbey, for instance, Molineux describes the architecture of that church for several pages, and pastes in no less than three illustrations to depict it. Otherwise, her visit to Portland and Chesil Beach in the April of 1862, for instance, clearly left her deeply inspired:

Page on which Molineux discusses Chesil Beach and includes a pasted image of such, 1862

“In the afternoon we drove to the Chisel [sic] Beach the waves were very grand indeed, falling with great violence on the Beach; it extends for eight miles and is often the scene of many fearful shipwrecks.”

Who was Eliza Jane Molineux?

As for our author, very little concrete information is known about Eliza herself, not being a particularly prominent figure of the area. Registry records suggest that she was born in 1819 and died in 1904, leaving behind no children or legal partner. This information is gathered from alternate registry and census records. But, for such a personal document, what does Eliza’s diary specifically tell us about the life of an unmarried woman in her 40s, during the height of Victorian Britain?

It would seem, disappointingly little – at the very least, not at first glance. As a travelogue, it avoids the more intimate details of Molineux’s life, instead focusing near entirely on the details of her journeys over the years, or the occasional spectacle she found worthy of note – such as Eliza’s amazement at the wonders of a microscope a friend had brought round, New Years Day 1862. We can, however, still make some inferences about our diarist’s life, from between the lines of the hefty volume.

Whilst it is immediately evident that our writer was educated to a decent level – as shown by her good English and fine penmanship – it is furthermore strikingly clear that Eliza was a wealthy woman. In the four years in which this travelogue spans, the sheer volume of time committed to travel and leisure was surely only the preserve of someone with access to a comfortable middle-class fortune. The variety and frequency of her trips, and even her mode of travel, which is often described as by carriage or even by steamer, alludes to a woman who could well afford a decently grand lifestyle.

Our book gives no obvious insight as to how Molineux funded this all. However, census records from the approximate time this diary was written list her profession simply as ‘shareholder’, later to become ‘annuitant’, and in 1891, ‘living on own means’. Eliza seemingly remained unmarried, and census records in fact describe Molineux as head of her household over her two sisters – Fanny and Emily – whom she lived with for most of her life.

This feeds into the next factor which we can infer about Molineux – she displayed a high degree of independence. With no prominent male caretakers obvious to us, it would seem that Eliza managed to retain considerable financial independence, at a time in British history when the law and society generally kept economic independence out of the hands of women. In this sense at the very least, Eliza would seem to have managed to eschew her expected gender role, during the height of their rigidity in Britain.

How did the diary end up in Bradford?

Considering how apparent it is that Eliza lived most of her life, including her latter years, in Kempsey, Worcestershire, the question remains as to precisely how the diary came to be found in Bradford by the relatives of our depositors. Those who donated this volume to us did not know themselves to be of any relation to Molineux. The complete story of how the family came to be in possession of the item is likely to remain, to some extent, a mystery.

We do know that following her passing in 1904, probate records reveal that Eliza’s effects – and therefore, most likely her diary too – were handed over to a George Henry Lomas, probably the child or grandchild of Molineux’s sister, Emily Lomas. George is described as having lived in London at that time; yet further from West Yorkshire. However, other records suggest that the Lomas family were, at some point, located in Lancashire; relatively speaking, only down the road from where the book came to be found.

As a partial result of the 100-year limitation on census records, the trail runs cold after that, leaving up in the air precisely when and how the diary made that journey into West Yorkshire, during the forty year gap between 1904 and the 1940s. We only know that at some point it did make that distance, to be sequestered behind someone’s cupboard – to eventually become something of a family keepsake for someone else entirely.

The diary can be found in the WAAS series, ‘Records relating to Eliza Jane Molineux of Kempsey, Worcestershire’. Donated with the book was a dossier of research done by the depositors, including some photographs they found relevant to their investigation.

Finding number: 899:1947 BA16106

What a fabulous find and interesting description of an independent woman in Victorian times. Thank you for sharing your passion.