World Earthworm Day

- 21st October 2021

Today is World Earthworm Day and a member of our Archive team who is also a committee member of the Earthworm Society of Britain has been unearthing soil and earthworm related materials from the archives!

Whilst there is a greater awareness about the threats to insect life and the recognition that pollinating insects are responsible for at least 1/3rd of all the food we grow, the importance of earthworms and their role in maintaining healthy soils on land for growing and recycling nutrients has been largely over-looked, although gardeners and farmers have undoubtedly understood their value to soil fertility. Secondly, whilst the UK has a long history of recording wildlife, earthworms have been hugely under-recorded compared with other wildlife such as birds or butterflies until relatively recently. Today thanks to the efforts of a small number of scientists, enthusiasts, and the Earthworm Society of Britain there are at least 31 species of earthworm in the UK and Ireland.

The Earthworm Society of Britain is a voluntary organization that plays a part in supporting scientific research to improve the conservation of earthworms and their habitats and educates and inspires people to take action to help earthworms. The society also runs the National Earthworm Recording Scheme and training courses for those who are keen to identify and record earthworms. The Earthworm Society of Britain’s Recording Officer established World Earthworm Day on the 21st October every year to raise awareness of the importance of Earthworms in contrast to the numerous events about the furry, glamorous or charismatic species of British wildlife such as Big Garden Birdwatch, Big Butterfly Count, Bat Week etc as earthworms were somewhat poorly represented.

Frontispiece to The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on Their Habits available at Ref 595.146

The 21st October was chosen because naturalist Charles Darwin published his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, with Oservations on their Habits (snappy title eh?) on this day in 1881 (a distillation of his many observations of earthworm behaviour and their contribution to soil processes). Like many of his other books about life on Earth it is nothing short of remarkable. We have a copy at The Hive at Ref: 595.146 DAR should you wish to read it. Darwin observed earthworms and undertook numerous experiments in his garden at Down House, Downe, Kent. Darwin’s book was the result of a 40 year study of them, including a 29 year experiment measuring the rate that a stone is buried by the burrowing activities of earthworms.

Earthworm stone at Down House in Downe, Kent. Darwin and his son Horace used it to measure the action of earthworms © Anthony Roach

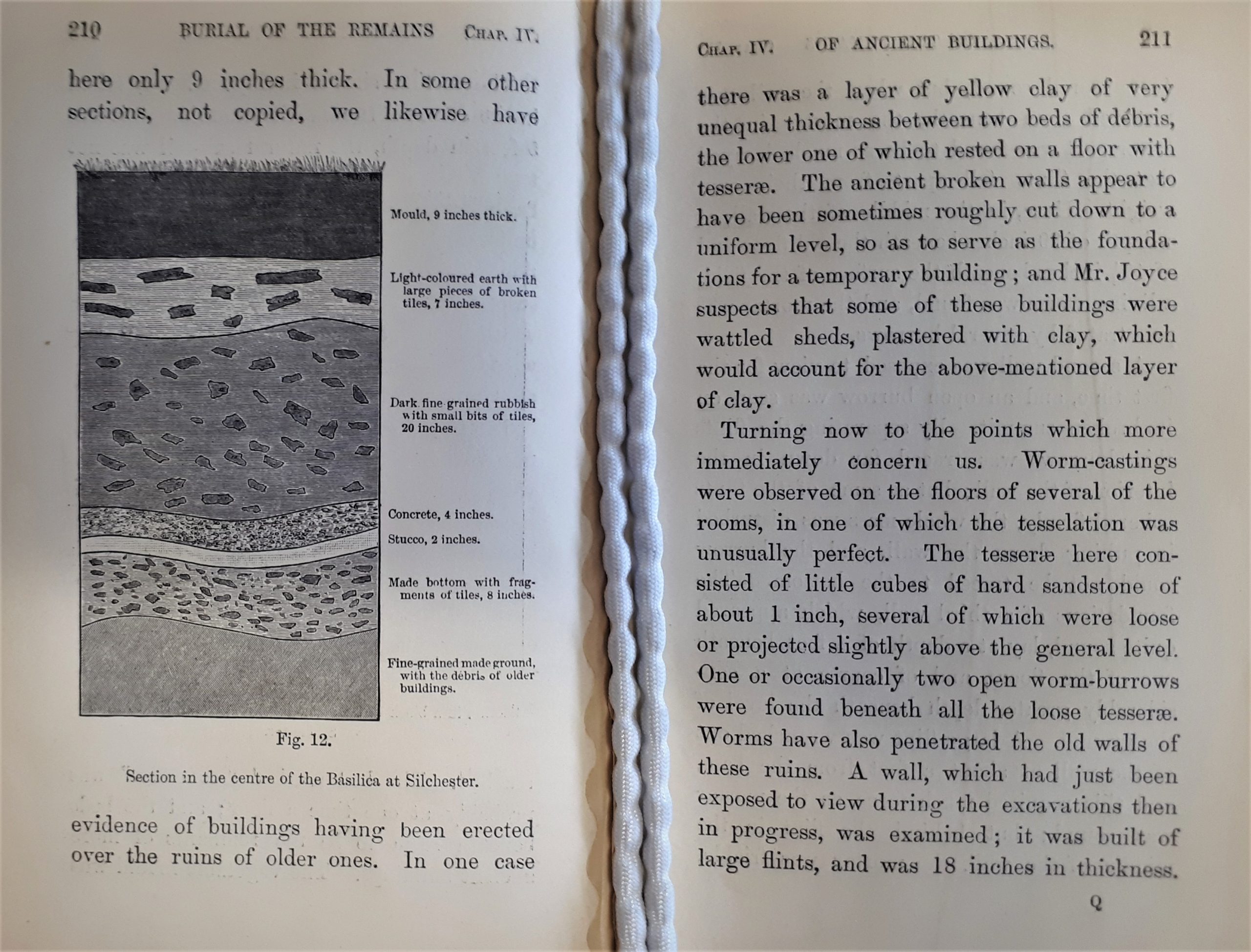

Darwin estimated that earthworms move 15 tons of soil per acre to the surface each year – a process we now call bioturbation which is well demonstrated in this video. Darwin also proved that through research of archaeological sites such as Silchester and Stonehenge that ancient buildings were slowly buried by the action of earthworms, along with other soil processes over time. In a bizarre coincidence, the author was once a student archaeologist at the Roman Silchester Town Life Project over several seasons! ‘Worms’ as it is affectionately known was very popular, initially outselling On the Origin of Species with 6,000 copies in the first year. It was Darwin’s last scientific book, published just six months before he died.

Insula XI, Silchester – Between 1997 and 2014 this site was excavated by The University of Reading Archaeology Dept. © Anthony Roach

Chapter IV: Burial of the remains of ancient buildings p210-11 © Charles Darwin, 1881

Darwin’s other well-known discovery was that earthworms do not select items randomly. He provided them with different types of leaves and observed how they were pulled down, finding that 80% of the leaves had been drawn in by the tip. Darwin then experimented further by providing the earthworms with triangles of paper – some broad and others narrow – and as with leaves the narrower end was dragged down first. He writes ‘If, moreover, worms acted solely through instinct or an unvarying inherited impulse, they would draw all kinds of leaves into their burrows in the same manner. If they have no such definite instinct, we might expect that chance would determine whether the tip, base or middle was seized. If both these alternatives are excluded, intelligence alone is left;’ Thus providing evidence that earthworms are intelligent organisms (Darwin, 1881).

Earthworms in the Ecosystem (c) Rick Kollath (all rights reserved)

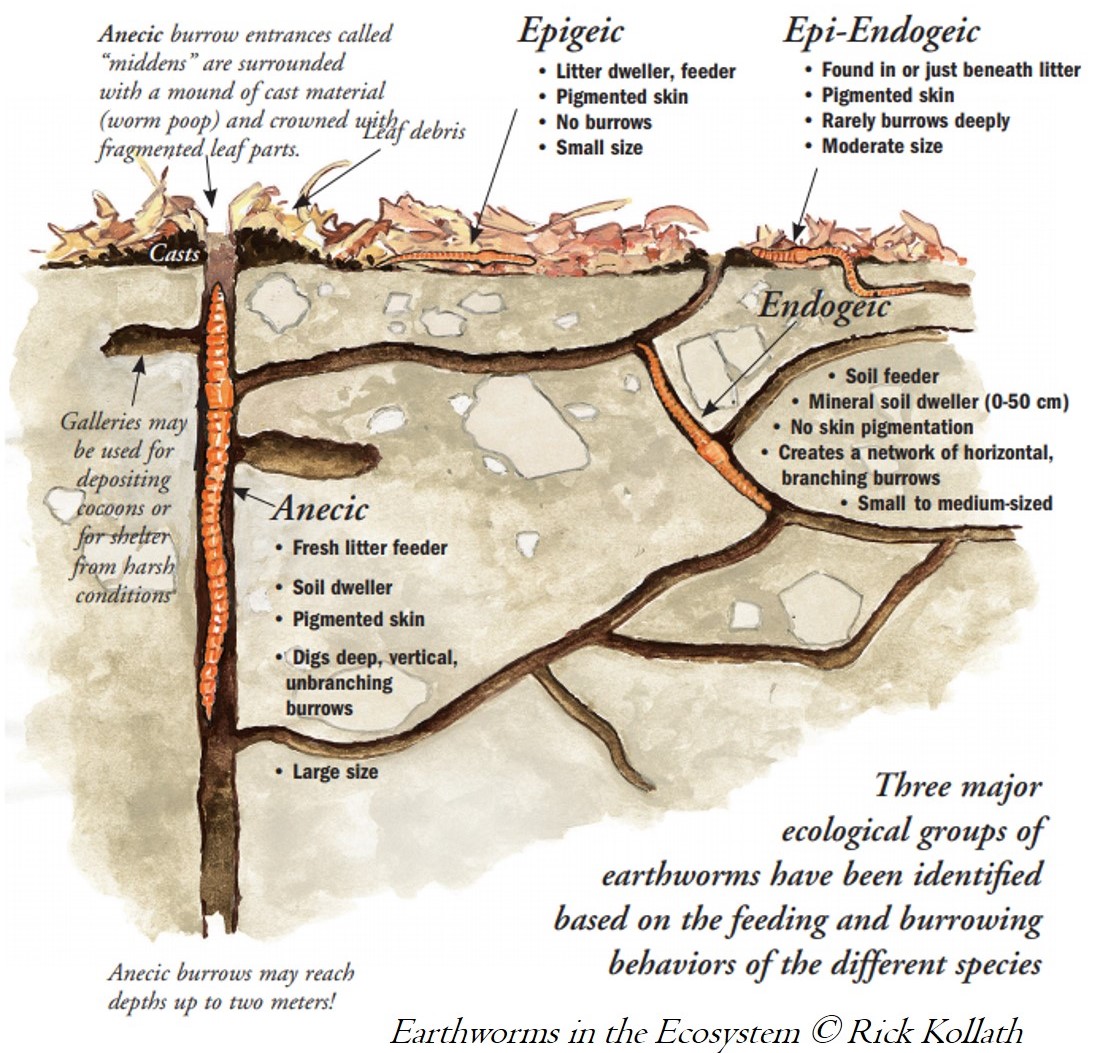

Today we know that there are three main types of earthworm groups or eco-types, as well as those that live within compost bins. The earthworms mentioned by Darwin that feed on and pull leaf-litter into their burrows such as Lumbricus terrestris from the soil surface are known as deep-living or Anecic earthworms and are among the largest species. They create a deep vertical burrow which often has an earthworm midden consisting of stones, leaves, twigs and other items pulled into the entrance – perhaps as protection against predators, rain, cold or drought. Meanwhile soil feeding or Endogeic earthworms are shorter, generally pale in colour and live within and feed on the soil directly living in small horizontal burrows. Surface feeding or Epigeic earthworms live within and feed on the decaying organic matter on the soil surface and are often reddish brown in colour.

Cartoon of Darwin and an earthworm, published in Punch c.1882.

Earthworm Senses

Darwin found that earthworms have no sense of hearing – being indifferent to being shouted at and various musical instruments including a piano, a bassoon and a tin whistle. However, earthworms in pots placed upon a piano retreated into their burrows when notes were played indicating they are sensitive to vibrations transmitted through the soil. Darwin also investigated earthworm’s sense of smell by blowing tobacco smoke and perfume to which they did not react. They did however respond to the smell of their favourite foods. Darwin experimented with giving captive earthworms many different foods and noted which they preferred. He found for instance that cabbages, horseradish, carrot and celery were also liked but herbs such as sage, thyme and mint were barely touched. We now know that earthworm bodies are covered with chemoreceptors. These are cells that allow the earthworm to taste things and are tiny sense organs which detect chemicals in the soil. The muscles make movements in response to touch and taste.

Earthworms and agriculture

Darwin understood, as we do today that the actions of earthworms in the soil, mix the soil horizons, incorporating organic matter into the soil. He calculated earthworms could produce up to 10 tons of humus (organic matter) per acre (Darwin, 1881) though Sir Albert Howard who incidentally has written an introduction to another copy of Darwin’s earthworm book available at The Hive who was an early pioneer and advocate of organic agriculture later thought this figure to reach 25 tons per acre (Howard, 1947). Darwin recognised the value of earthworms to maintaining agricultural systems as we do today for growing food and said that ‘It may be doubted whether there are many animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world as these lowly organised creatures’. Growing food in Worcestershire in the Vale of Evesham and Pershore has been an integral part of the landscape in the 19th and 20th centuries, shaping the people and the economy and which, as a way of life has been documented through our Market Gardening Heritage Project.

Onions grown during the war. Image copied after being lent by Ivy Smith as part of the Market Gardening Heritage Project.

Growing fruits and vegetables such as apples, asparagus and seasonable produce including hops and other arable crops continues to be vitally important to the regional economy. However, with the need to grow much more food during and after the Second World War which began with the establishment of the War Agricultural Executive Committee (who oversaw an increase of productive land of 1.7 million acres between 1939 and Spring of 1940) traditional Market Gardening growing of vegetables, fruit, herbs and cut flowers largely disappeared. Whilst there a few traditional Market Gardeners that operate today, the mechanisation of farming, changes in farming policy by the government, establishment of large-scale commercial horticulture and with it a need for more space and higher yields to cater for consumers changing tastes compared with foods traditionally grown in the UK in the past. New and exotic crops such as Pak Choi and micro herbs supplement Brassicas, field vegetables and abundant apples and plums today.

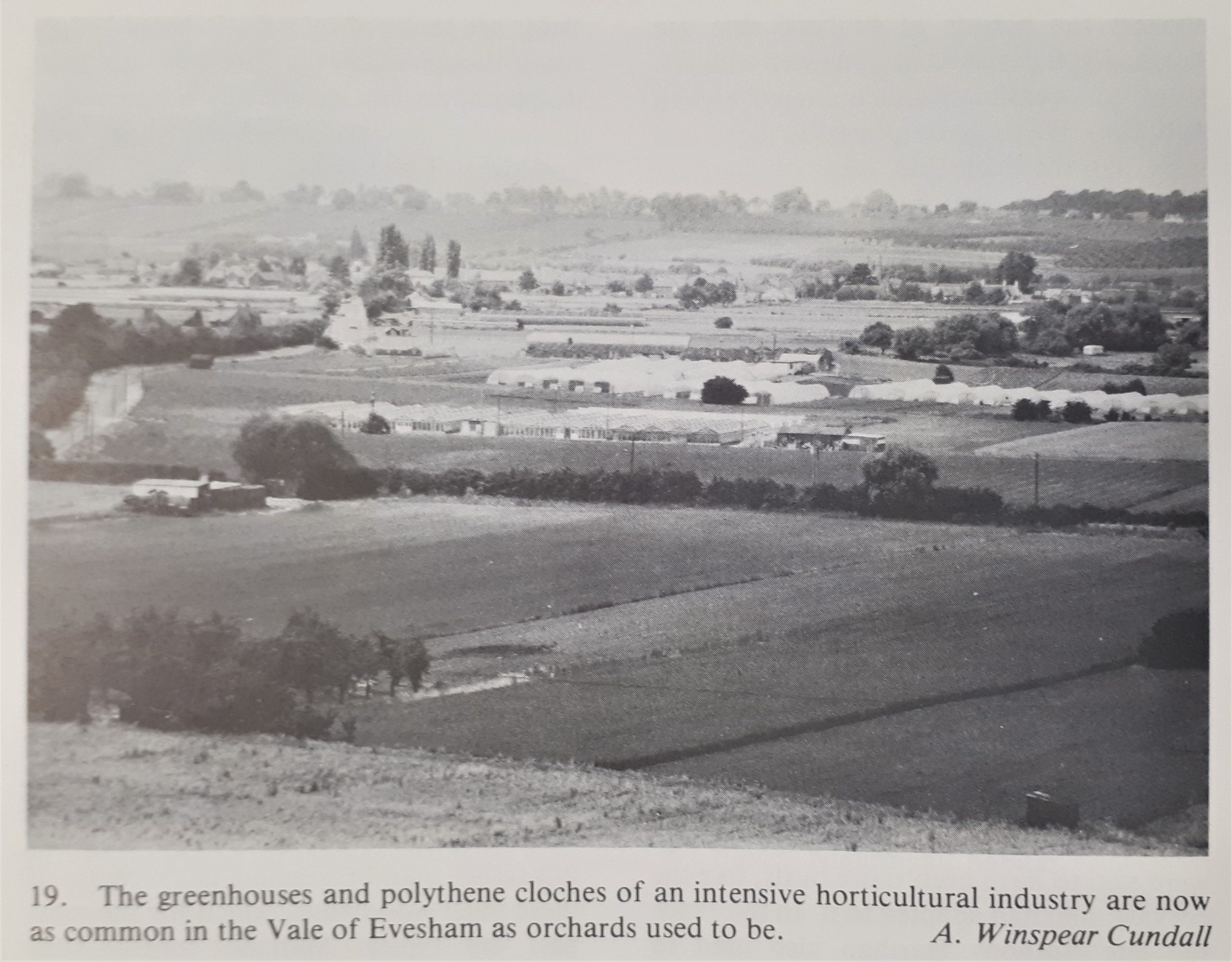

The greenhouses and polythene cloches of the Vale of Evesham in The Birds of West Midlands p91 © West Midlands Bird Club 1982

Whilst this has been good for ourselves and has led to some increase in self-sufficiency, the widespread impacts on wildlife have been dramatic, as reported by the UK State of Nature report in 2016. Based on the Biodiversity Intactness Index of 218 countries assessed, the UK was ranked 189th Due to changes in government policy since the 1970’s production-driven farming practices such as the loss of mixed systems, the change in sowing seasons and increased use of fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides, the loss of wildflower meadows and semi-natural habitats such as hedgerows, ponds and field margins has led to a catastrophic decline in farmland birds, insects and mammals. The recognition that the UK has become one of the most nature-depleted countries has again been recently reported as its level of biodiversity intactness is below the safe limit of 53% according to a new report by the Natural History Museum, London.

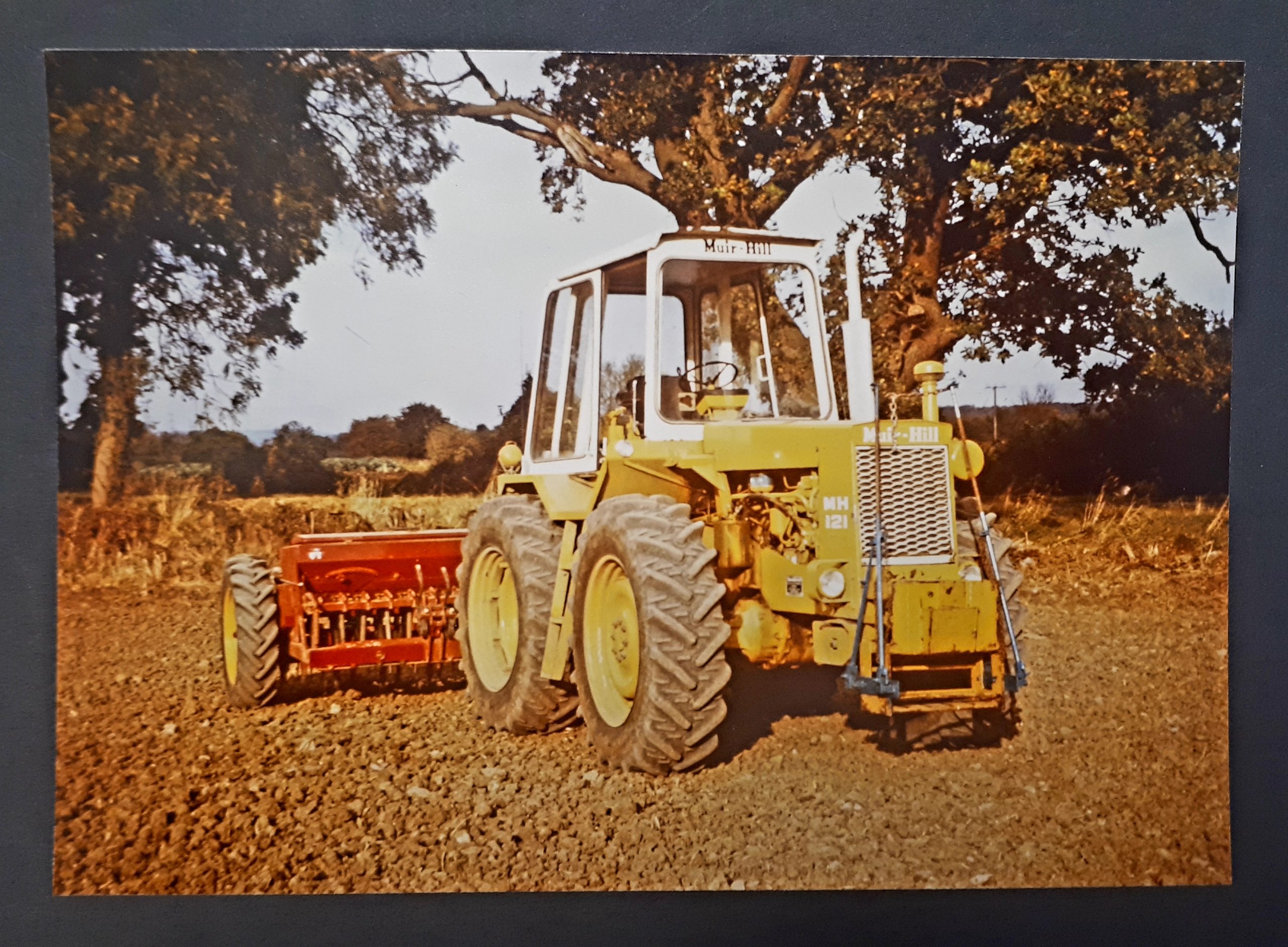

120 H.P. Tractor Ploughing Patchett’s Farm, Tardebigge Ref: 899.156 BA 1332 WPS 55320 © J. Wormington Esq.

80 H.P. Tractor and Cultivator, Patchett’s Farm, Tardebigge Ref: 899.156 BA 1332 WPS 55317 © J. Wormington Esq.

Held in our Archive at Ref: 899:156 as part of our Worcestershire Photographic Survey are some historic examples of mechanised farming in action from 1980 which include ploughing, cultivation, seed bed preparation and drilling at Patchetts farm in Tardebigge, Stoke Prior. These techniques haven’t changed radically since this time, though perhaps the scale in which they are undertaken in parts of the UK and around the world has.

Tractor preparing seed bed, Patchett’s Farm, Tardebigge Ref: 899.156 BA 1332 WPS 55319 © J. Wormington Esq.

4 Wheel Drive Tractor and Seed Drill, Patchett’s Farm, Tardebigge Ref: 899.156 BA 1332 WPS 55318 © J. Wormington Esq.

The question is, what have these farming practices meant for earthworms? Has intensive agriculture led to a reduction of species in the UK? Well, there isn’t simply enough data to conclusively show that all earthworms are in decline as a result of some farming practices. However, a recent study demonstrated some evidence that there was a decline in surface feeding earthworms compared with soil feeding and deep living earthworms based on a small number of farmland surveys. The average field had nine earthworms per spadesful, but the best fields with healthy soil had three times that number. It suggested that fields that had been overworked had fewer earthworms. More than half the farmers were so alarmed by the results they pledged to change their practices.

Soil feeding earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa © Victoria Burton

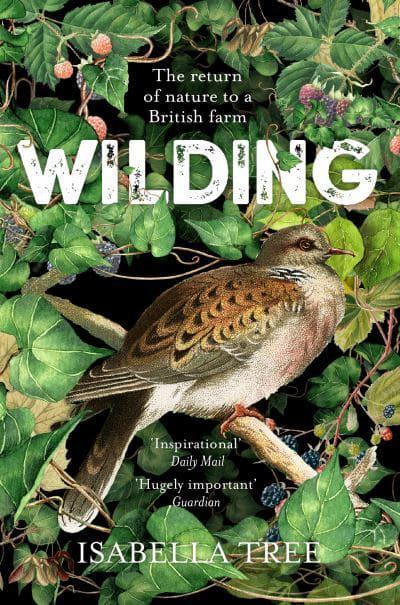

With increased concerns over the impact of farming methods what it clear is more data is needed but alarm bells have been rung over soil fertility as well as a need for farmers to balance growing food whilst also improving biodiversity. The concept of Re-Wilding Britain to increase biodiversity such as that taking place on The Knepp Estate (which has led to the successful re-introduction of Storks not seen for centuries) is one such example and the story is passionately told in Isabella Tree’s book Wilding who owns the farm with husband Charlie Burrell. The return of field margins, hedgerows and use of strip farming to increase habitats for wildlife and food for pollinating insects is another. However, there isn’t one solution for all farmers or growers and their survival is increasingly uncertain due to the impacts of Brexit and climate change. The challenges of growing enough food, whilst increasing biodiversity and reducing the impacts of climate change are huge problems requiring innovative solutions which has led to Prince William’s recent Earthshot Prize.

Wilding: the return of nature to a British Farm which tells the story of how The Knepp Estate farm was ‘Re-wilded’ to increase biodiversity © Isabella Tree

Whilst it may be unclear whether earthworms are declining, what is clear is that the services they provide (for free!) are vital to soil structure and fertility. Charles Darwin referred to earthworms as ‘nature’s ploughs’ because of this mixing of soil and organic matter. This mixing improves the fertility of the soil by allowing the organic matter to be dispersed through the soil and the nutrients held in it to become available to bacteria, fungi and plants. Earthworms also play an important role in decomposing organic matter which releases nutrients locked up in dead plants and animals and makes them available for use by living plants. Earthworms have also become known as ‘ecosystem engineers’ due to their burrowing actions which change the structure of environments. Their burrows create pores through which oxygen and water can enter and carbon dioxide leaves the soil.

With this in mind, reduced or no till farming and no dig systems as pioneered by Charles Dowding an organic grower and advocate of no dig gardening since 1983 can help to reduce the disturbance to earthworms and other soil organisms and other benefits include reduced soil compaction, erosion and loss of organic matter. Therefore our understanding of the soil and how we manage our soils in our garden, allotments and farms now and in the future sustainably will affect the biodiversity held within it and the success of soil organisms.

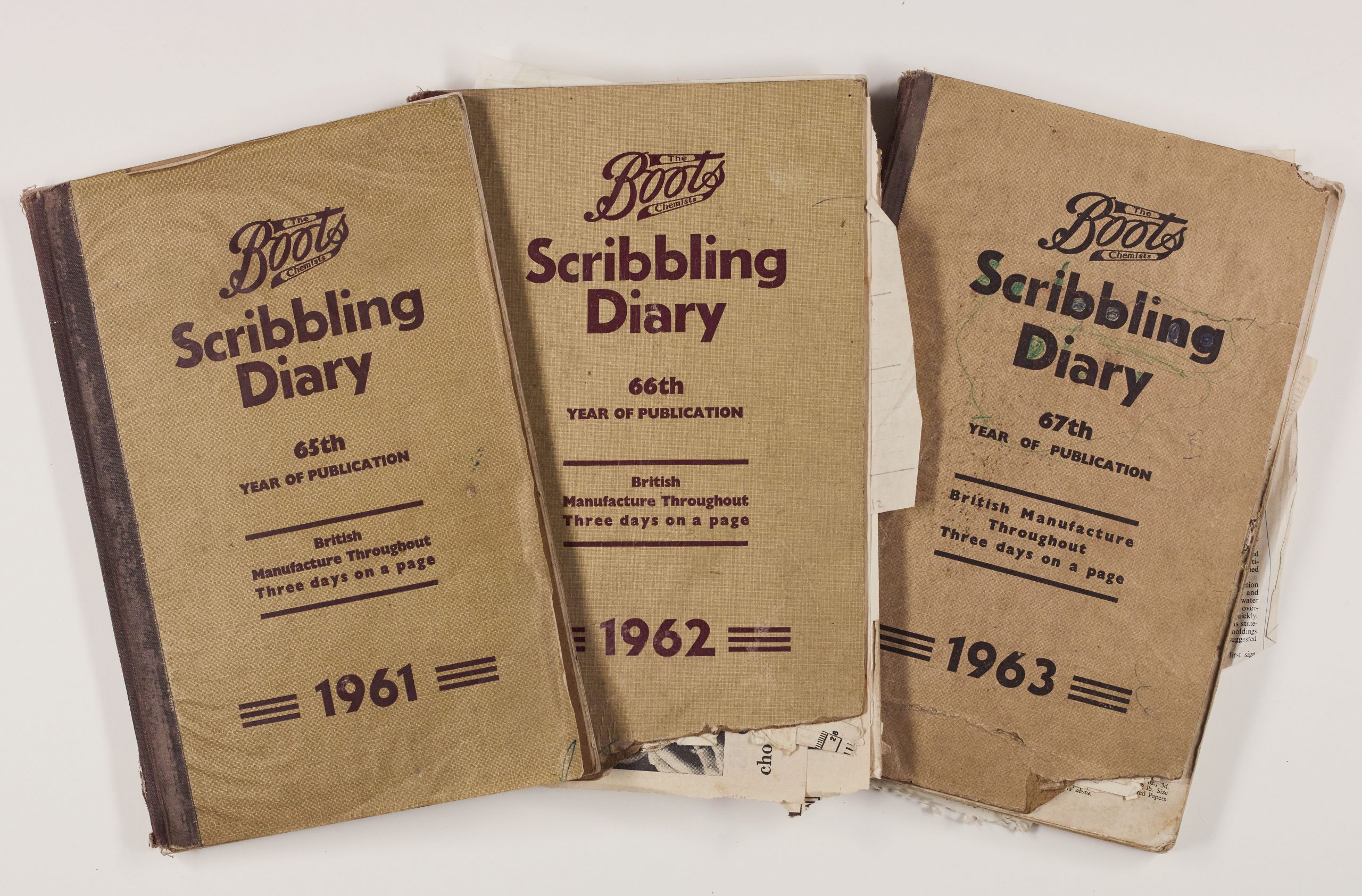

Wilfred George Cole’s Administrative Diaries at Sandilands Nursery, 1961-1963 Ref: 705.1739 BA16269.2 © WAAS

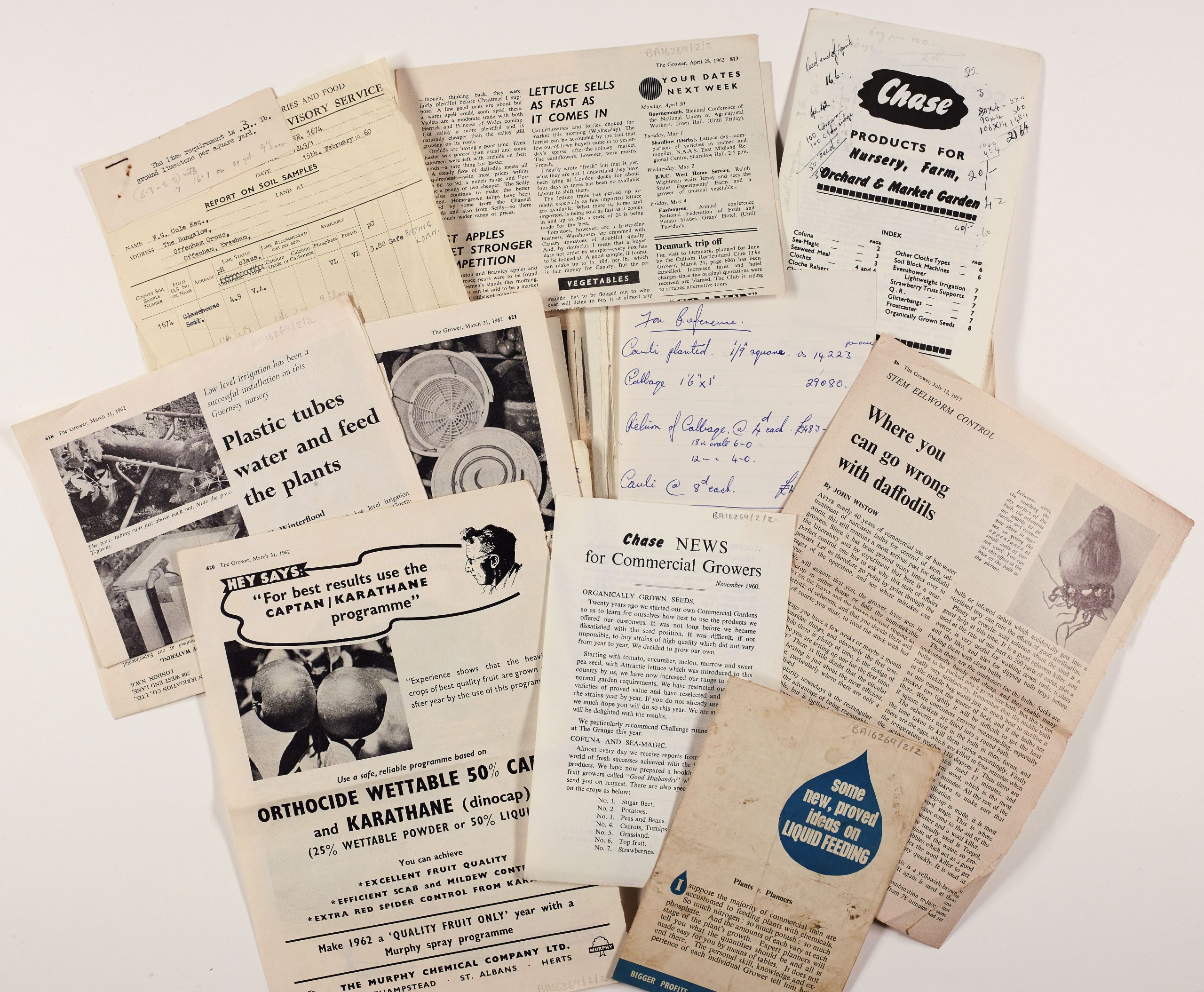

Someone who clearly recognised the importance of healthy soils was Wilfred George Cole of Sandilands Nursery whose administrative diary is held with us at Ref: 705:1739 BA16269/2/2 which covers the early 1960’s. Wilfred’s diary of his nursery which included running a large glasshouse (if not others, though difficult to confirm without further study!) records the weather; financial matters; maintenance and repairs of the estate; the distribution of labour; farming; organic growing; and crop cycles and his notes include correspondence; advertisement leaflets; handwritten administrative notes; envelopes.

Ephemera such as leaflets, growing advice and notes found in W.G. Cole’s 1962 Diary at Ref: 705.1739 BA16269.2

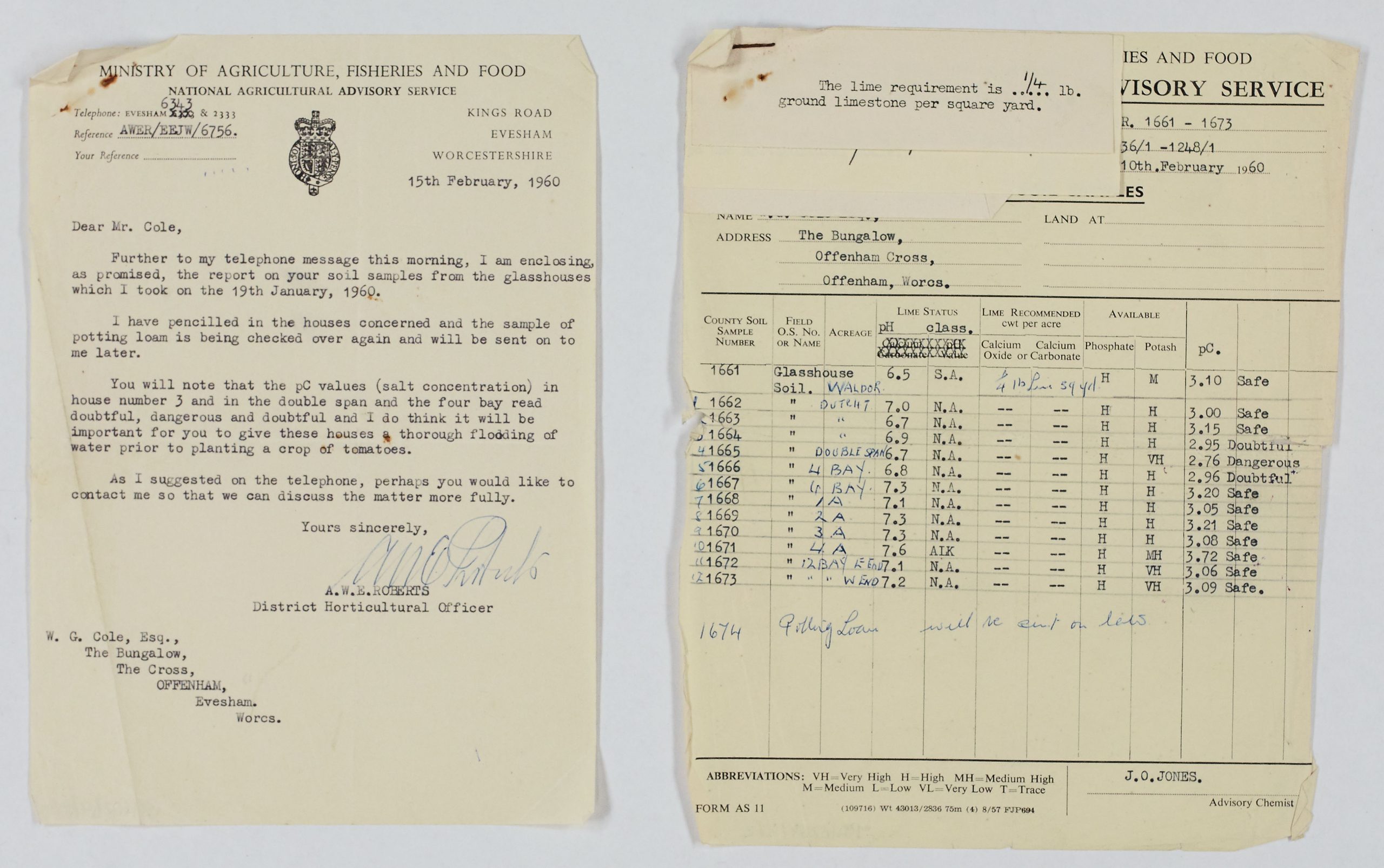

He was clearly passionate about his soil with several reports on soil samples from what was then the “Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food”. The sample records soil PH, Phosphate, Potash and the report confirms the Lime Requirement of ¼ lb ground limestone per square yard. Very similar to today a standard soil analysis package measures soil acidity (pH) and estimates the plant-available concentrations of the major nutrients, phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and magnesium (Mg) in the soil. Alongside this was recorded a p.C value, thankfully the letter describes this as salt concentrations which meant that some of the samples were dangerous or doubtful in terms of the growing medium and confirms that Wilfred Cole was intending to grow tomatoes, which we all know can be fussy to grow in any greenhouse!

Soil Sample report on Glasshouse for W.G. Cole by Ministry for Agriculture Fisheries and Food at Ref: 705.1739 BA16269.2 © WAAS

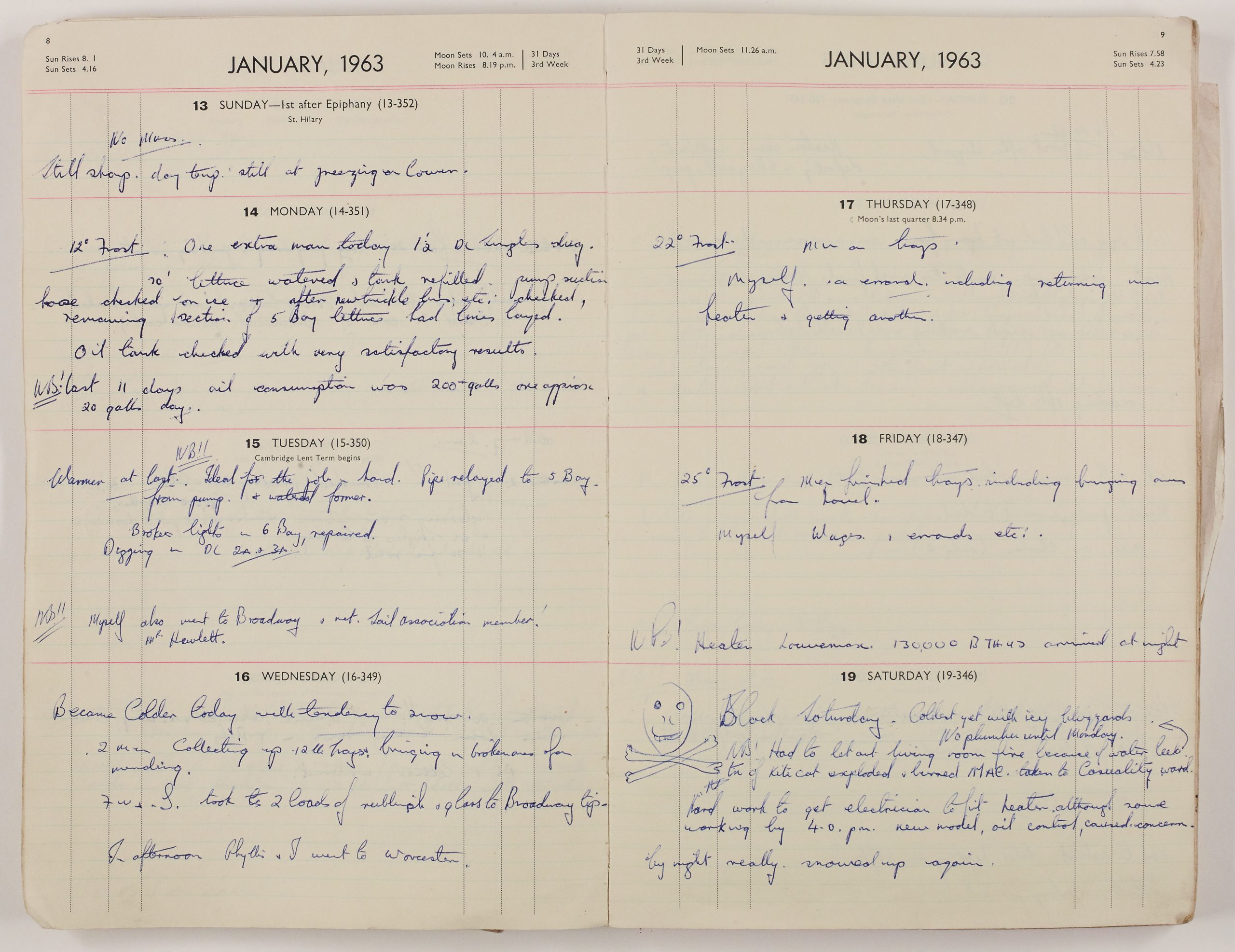

Some of Wilfred’s diary entries such as ‘Black Saturday’ are very amusing as they highlight the challenges we all face in trying to get a work-life balance and failing miserably and the challenges of the weather in a given growing season. He writes how on the 19th January which was ‘Coldest yet with icy blizzards’ there was a water leak, and with no chance of a Plumber for two days he had to get an electrician to fit a heater, later a can of Kitikat exploded and burned ‘MAC’ taken to casualty ward! Eeek! His diaries also record holidays and trips taken, whether they are successful or not and he seems to share in our woes when it comes to the August Bank Holiday weekend weather!

W.G. Cole’s diary for January 1963 describing ‘Black Saturday’ at Ref: 705.1739 BA16269.2 © WAAS

How can you help earthworms?

Soils in gardens, allotments and in the wider landscape are highly dynamic places, the depths of which I think we will never wholly understand, but we can but try. The topography (if there are areas that are very exposed, compacted, sandy with low organic material, there may be fewer earthworms). Understanding your Soil PH and type is also an important factor and the charity Garden Organic produce an excellent Soil Information Pack which can help.

Earthworms prefer slightly alkaline or neutral loam or clay soils. Sandy soils tend to leach more nutrients and earthworms do not thrive in large numbers in very acidic soils. Providing plenty of organic material through mulching beds or borders, using leaf-mould or peat-free compost, reducing how often you work the soil and providing wild areas with compost heaps are just some ways you can help improve habitats for earthworms in your garden.

Thank you for an absolutely fascinating post. I had no idea earthworms were so interesting and important and have learnt a great deal.