‘Tom’ the Burlingham Bird

- 30th March 2022

This blog explores the story and conservation of a mummified Bird found in our Archive and the much larger story about the exploitation of birds and people in the 19th century.

Tom, our Trainee Archivist, had originally believed himself to have found a pair of leather gloves poking out from the top of a file, sandwiched between an itinerary for an agricultural tour of West Germany and concept art for a fertiliser advert. It was only after opening up the folder that it became clear there were no gloves – but the dehydrated carcass of a bird.

The Burlingham Company

The deposit in which we found the bird was one of a significant size and of notably varied content. It is one of several we hold which was formerly in the possession of the Burlingham family, and before that Henry Burlingham & Company (oftentimes “H Burlingham”, or later just “Burlingham”). Family and business alike were both based in Evesham.

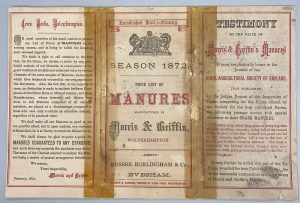

Patriarch, progenitor, and namesake of H Burlingham & Company, Henry Burlingham began business in the early Nineteenth Century as a merchant agent and merchant of a wide range of goods – predominantly coal and its related products. Running the business with, and eventually passing it down to his two sons, the company was granted LLC status in 1919. Though running a diverse portfolio, the range of Burlingham business interests narrowed throughout the 1900s until they were known primarily as sellers of construction materials, garden machinery, and fertiliser.

The company was sold to Norcros PLC in 1987, after which it’s tricky to say what happened to Burlingham & Co. Whilst Norcros exist today as a conglomerate supplier of bathroom and kitchen furnishings, Burlingham is not listed amongst their current subsidiaries. Otherwise, there is very little mention of the company anywhere.

The Deposit

What was extraordinary about discovering the bird was the unexpectedness of finding it amongst business records, of all things. The most baffling part, however, is the way in which the bird was seemingly filed by the company, and in such an ordinary and unceremonious manner.

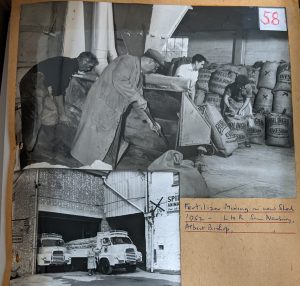

One element of the deposit consisted of five large lever arch folders, labelled only vaguely as ‘Old Records’. This specific series of records could be described as the company’s rendition of a formal archive – organised loosely by date and containing only records that relate directly to the business’ functioning: deeds, contracts, financial statements, invoices. Between them, these folders contained approximately 123 individual items, with dates of original production from as early as 1820 and ranging through to as late as 1987.

The bird, further, was evidently not there by mistake, as it can be found, fully itemised and described, on the inventory handlist which was provided alongside these folders;

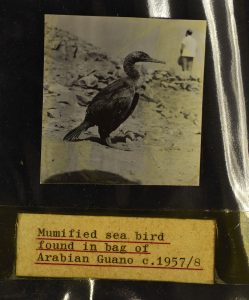

“63 – Mummified seabird found in bag of Arabian Guano 1959”.

Considering that all the folders were of the same brand and style, and that folder 5 contained records dated as late as 1987 – the year when the company was sold and seemingly concluded business – it is entirely possible that the records were compiled after this date. Whoever did so clearly deem the bird as a worthy record of the Burlingham Archives. Precisely why it was kept in the first place, preserved, or kept with the company records will likely remain a mystery, and we could not find any hints to illuminate us.

Further Investigation of the Burlingham Bird

It is fair to say that whilst we do have some objects held in our Worcestershire Archives, a mummified bird filed in a plastic pocket was hugely surprising all the same! The bird was ‘filed’ – its place as important as the other key events in the history of the business of Burlingham & Co., Evesham. Either side contains photographs of the premises charting it’s changing fortunes from the a catalogue of products sold, adverts and circulars sent out to clients and even papers related to the resignation of one of the Directors of the company from the 1930’s. I was immensely excited by the find, because I am passionate about nature, especially birds and insects.

Prior to coming to the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service, I had trained in UK Biodiversity at the Angela Marmont Centre for UK Biodiversity and spent time working on curatorial projects and using Natural History specimens for outreach at the Natural History Museum, London working in the Science Education team. I was excited by the Burlingham bird find and wanted to learn more about what species it might be, but also, in conversation with the Collections team, how best to conserve and safely store the specimen in our archives.

The Mummy Bird

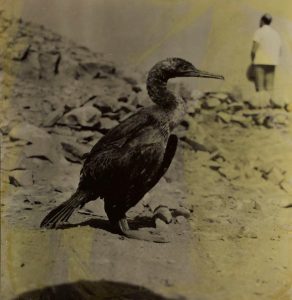

As you can see from the photo above it was described as ‘Mummified sea bird found in bag of Arabian Guano c.1957/8.’ When I first examined it, I thought it most resembled either a cormorant or a shag having been used to seeing both around the coasts and estuaries in Devon. Whilst the cormorant and shag look very similar, it is possible to tell them apart both by their colouration and breeding plumage, where found and by their behaviour (though of course not possible in this case). Shags are birds of the coast who occasionally can be found inland on rivers but are usually alone, whilst cormorants are more likely to be found by the coast inland, but often in groups, learn more by visiting how tell the difference between a cormorant and a shag.

Having reviewed the different species of cormorant and shag found in Arabia using the image supplied with the bird and the morphology of the mummified bird itself, it most closely resembles the Socotra cormorant (Phalacrocorax nigrogularis) – endemic to the Persian Gulf and the south-east coast of the Arabian Peninsula. Admittedly, there is no way of knowing that the image supplied is of the species discovered in Guano, however, with the word Velox on the back of the image, Tom proved it must be photographic paper and therefore an original photograph. Also given the effort gone to ‘file’ the bird away, the photograph may well depict the species accurately.

Fishing for Cormorants

My first impressions of the bird in the black and white photograph was that it more closely resembled a shag which are often described as slender bodied with a long slender bill, However, having compared the image to photographs of the Socotra cormorant, which is also described more rarely as a Socotra shag, the fact the photograph supplied appears to show white on the neck is consistent with many other images of Socotra cormorant based on the following description

‘The Socotra cormorant is an almost entirely blackish bird with a total length of about 80 centimetres (31 in). In breeding condition, its forecrown has a purplish gloss and its upperparts have a slaty-green tinge, there are a few white plumes around the eye and neck and a few white streaks at the rump. Its legs and feet are black and its gular skin blackish. The birds are highly gregarious, with roosting flocks of 250,000 having been reported, and flocks of up to 25,000 at sea.’

It was important for us to get a second opinion and I contacted a former colleague Hein Van Grouw, Senior Bird Curator at the Natural History Museum at Tring who could offer some expertise on both the species and its storage requirements. He was of the same opinion that based on the evidence it was in his words ‘Indeed, a cormorant of some sort’ and most definitely a juvenile bird (chick).

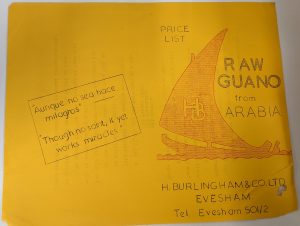

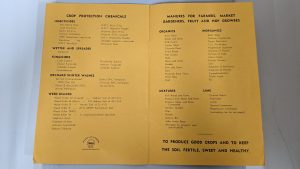

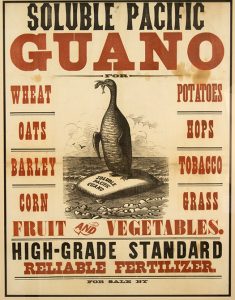

Advert for Bird Guano Burlingham & Co. 2nd October 1950 BA12963.6.68

He was of the opinion also that it must be a species that was breeding in the area where the Guano was collected and considering this was Arabia, the bird was probably already dead and was “harvested” together with the guano. Therefore a Socotra cormorant was very likely or alternatively the Great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo). In both cases, they are of the genus Phalacrocorax.

Apparently, whilst there isn’t much information on this species’ diet, like all cormorants its dives for its food, which is primarily fish. Older reports suggest that it can stay submerged for up to 3 minutes, which is high for a cormorant and suggests that it would be capable of deep diving.

Whilst the circumstances of the young chick’s death are very sad, populations of the species itself are not doing well. Since 2000, the Socotra cormorant has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, on the grounds of its small number of breeding localities and ongoing rapid decline. The decline is caused by coastal development, disturbance and marine pollution near its nesting colonies. In the northern part of its range alone, about 12 colonies are known to have disappeared since the 1960’s.

Cormorants of the World

As Mark Avery writes in Remarkable Birds, there are as many as 40 species of cormorant across the world occupying every continent. Cormorants catch their food by swallowing fish whole, however they need to make sure they position the fish correctly, as many have spiny fins that would make swallowing them painful or difficult to process the wrong way around! (Avery, M., 2016)

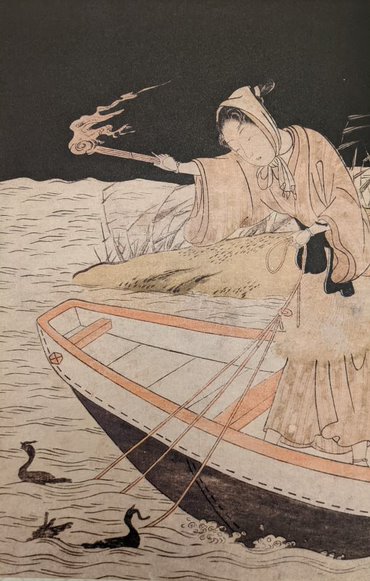

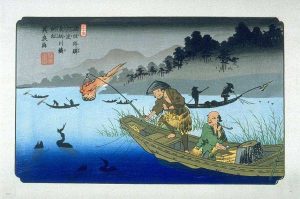

Unsurprisingly, their apparently gluttonous behaviour has led to them being an enmity of fishermen, however cormorants have been trained and employed by peoples in China and Japan to catch fish for thousands of years. The cormorants learn to bring captured fish back to their owners and are rewarded at the end of the fishing trip with a portion of their catch (Avery, M., 2016). This behaviour was shown in the BBC series Wild China.

The use of Japanese cormorants (Phalacrocorax capillatus) in a tradition called ukai (鵜飼) (literally meaning ‘raising a cormorant’) is well documented but amazingly the domestication of cormorants in this way wasn’t restricted to Asia. As Mark Cocker writes in Birds and People, it may have been practised by none other than Worcester’s well-known monarch Charles I. (Cocker, M., 2013 p.151)

Charles’ father James I (as well as Louis XIII of France) appear to have been keen to train cormorants for fishing and James invested a small fortune in cormorants until he died, keeping a large stock of birds in London and taking them on hunting expeditions to Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. James I also tried to export the art, sending birds to Venice, presumably as a gift to the doge, but the Duke of Savoy intercepted the king’s Master of the Royal Cormorants and stole them! It appears that Charles I kept the pastime alive as described in John Ray’s 1678 work Ornithology:

‘They are wont…in England to train up Cormorants to fishing. When they carry them out of the rooms where they are kept to the fish-pools, they hood-wink [place a hood over their heads] that they be not frightened by the way. When they are come to the Rivers they take off their hoods, and having tied a leather thong round the lower parts of their Necks that they may not swallow down the fish they catch, they throw into the River. They presently dive under water, and there for a long time with wonderful swiftness pursue the fish…[….] Then their Keepers call them to the fist, to which they readily fly, and little by little one after another vomit up all their fish….[…] …for their reward they throw them part of their prey they have caught…’ (Ray, J, 1678 in Cocker, M., 2013)

Bird Guano and its ecological impact

Our juvenile mummy bird which we now call Tom, in honour of our Trainee Archivist who found him sadly tells us of a much darker story of exploitation of the natural world. Evesham by the middle of the 20th century was a centre of agricultural production and market gardening and had been since the 19th century, the need for minerals such as phosphorus (P), potassium (K) (also known as Potash), magnesium (Mg) and ammonia as fertilisers to produce ever higher-yields was essential. Flyers from Burlingham and Co which alongside a wide variety of agricultural sundries, describe the availability of organic and inorganic fertilisers for commercial growers and gardeners. Organic fertilisers which are familiar to us today including blood and bone whilst inorganic fertilisers include magnesium sulphate and potash.

However, prior to the widespread use of inorganic fertilisers such as sulphate of ammonia following the breakthrough of the Haber-Bosch process (which revolutionised the production of nitrogen-fixing fertilisers to produce ammonia) the use of Guano as a fertiliser had been established in the early 19th century due to exploration and the establishment of colonies, including the British Empire. As Mark Cocker describes in Birds and People, the exploitation of Guano by rich nations such as Britain, America and subsequently Australia it illuminates “a pattern of consumption without limit, and appetite without self-restraint, it appears now almost as a metaphor for the entire impact of capitalism upon the biosphere” (Cocker, M., 2013, p.147).

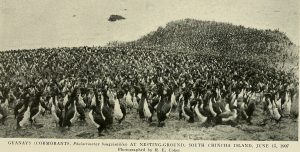

The origin of Guano production began in coastal South America with the Inca who long exploited a form of derived manure that they had named huana. The original word was modified and became known as guano. The Inca obtained their supply of this high-quality fertiliser, which is rich in phosphates and nitrates, from a series of islands close to the current Peruvian coast. These sites were thickly populated by a range of seabird species but dominated by three in particular, one of which was the Guanay Cormorant, the others are the Peruvian Booby and Pelican. The dung middens amassed by these Seabirds are uniquely fertile because of desert-like levels which minimise leaching of the precious nitrate content.

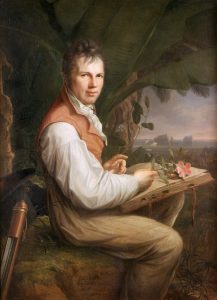

It is with some sense of irony that a German explorer, Alexander Von Humboldt who is today recognised as one of the greatest naturalists of all time through his observations, wrote of the use of guano for agricultural purposes and spurred both American and European merchants to undertake trials using guano. By 1841, 2000 tonnes were dispatched to Liverpool and within a decade the main centre of guano mining, the seabird colonies of the Chincha Islands, supported a small town of 3,000 inhabitants and an export industry involving half a million tonnes annually (Cocker, M. 2013).

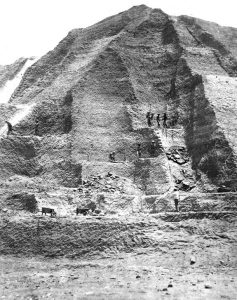

Whilst it was an excellent fertiliser the mining and conditions to extract rock-like cap deposits some 50m thick was hellish (Cocker, M. 2013). As described here guano extraction was dangerous and living conditions were poor. Most extraction was performed by indentured Chinese laborers who worked in slavery-like conditions, and who were economically bound to earn back their transport, board and lodging costs before making a profit. Before slavery was outlawed in Peru in 1854, guano was also extracted by some enslaved people, as well as convicts, conscripts and army deserters. The fine stinking powder was so noxious it caused the nose or lips to blister and burn. The poorest involved in extracting the material certainly were not those who benefited the most either, instead, it was rich industrialists.

You don’t have to go far in the UK to find an example of this either. The beautiful National Trust run Tyntesfield near Bristol is built largely on the profits and subsequent wealth from the guano trade in Peru by A. Gibbs & Son a company established by Antony Gibbs. In 1842, the Peruvian government granted A. Gibbs & Sons a license to export guano (nitrate-rich seabird droppings) to Britain and by 1847, they had secured a monopoly for the British guano trade on the Chincha Islands. As industrial agriculture boomed in Europe, so too did the demand for guano, which at the height of their operation earned £100,000 a year – over £8,000,000 in today’s money.

Whilst their exploitation of guano was to have a profound impact on the bird colonies at Chincha, thanks to William Gibbs at least, during the time the guano business operated (1842 to 1861) workers’ conditions, including pay and medical care, improved under Gibbs’s control. In 1842 control of Antony Gibbs & Sons passed to sole partner William Gibbs. The profitability of the guano trade inspired a popular music hall ditty ‘William Gibbs made his dibs, Selling the turds of foreign birds.’

So what of the Chincha guano deposits themselves and their impact on seabirds? By the end of the 19th century, an estimated 20 million tonnes had been exported. Guano, which had accumulated over hundreds, if not, thousands of years scraped down to bare rock. The underpinning ecology itself subsequently suffered. The anchoveta, a fish that occurs in vast numbers off the coast of Peru (due to the upwelling of nutrients from the Humboldt Current) was and still is eaten by seabirds and the result was the vast guano mountains. Remove the anchoveta by overfishing and you also reduce the capacity for these guano mountains to return.

Nest of Peruvian Booby shown to be made almost of pure guano, taken at La Vieja Island, Paracas National Reserve, Peru

The nutrients fed by the Humboldt Current also feed many other species including Sea-lions and Humboldt penguins. Whilst the Peruvian government recognised the inherent destruction of these ecosystems following the methods of European and American merchants, some seabirds such as the Humboldt penguin and Peruvian diving petrol have not recovered. The guano caps created by the Guanay cormorant and Peruvian booby were nurseries where other species dug their nest chambers. The decline of the Humboldt penguin has been attributed to the guano harvest of the 1800s, which led to the destruction of breeding grounds and human disturbance.

Tom preserved for the future

With the decision to keep Tom, whom we believe is a young Socotra cormorant chick, the specimen has since been removed from his original plastic packaging because of the threat of insect pests such as Anthrenus verbasci (other species described in detail here). In consultation with Hein Van Grouw at the Natural History Museum, guidance set out by the National Archives under 5.7 Pests ‘Managing Mixed Collections’ and Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections (Carter, D. & Walker, A. K., 1999) it has been be conserved in an air tight container with acid free tissue, in a temperature and humidity controlled conditions separate to other collections to reduce likelihood of infestation.

As shown by the material we have on Burlingham & Co and as early as the 1950’s, we have been able to produce inorganic fertilisers, rather than wilfully exploiting the ecology of wildlife and their ecosystems, whose damage in some cases has been irreparable. We sadly know very little about the guano extraction from Arabia, but we can be certain that other case studies have demonstrated the detrimental impact on the seabird colonies due to phosphate mining and extraction.

As late as the 21st century, Australia has been extracting guano from Christmas Island to the detriment of Abbott’s Booby (Papasula abbotti) which had plans to recommence mining operations but thanks to lobbying as late as 2017 it now appears to be winding down operations. We will probably never know why Tom was kept, but it demonstrates the fascination, unpredictable nature and decisions that shape collecting. Tom also illustrates sharply how an object has the power to tell a much wider story about our own history and how we can learn lessons from it.

Anthony Roach & Tom Poole

Every effort has been made to trace and credit copyright of any published images where appropriate. If there are any images that have not been credited appropriately, please do not hesitate to contact us at WAAS and this will be rectified accordingly.

Other Sources used:

Birds and People Author: Cocker, M. (Author) (Illustrator) Tipling, D. 2013 – Ref: 598 COC

Remarkable Birds Author: Avery, M. 2016 – Ref: 598 AVE

What an amazing story! A great piece of detective work and research, well done!