Henry Usborne’s Prescription for World Peace: A Global Government

- 19th May 2022

Our archivists have recently completed the cataloguing of a large collection originally belonging to Henry Usborne, MP for Birmingham and activist for world peace. His records are fascinating for anyone interested in British post-war politics, international governments, or responses to the threat of Nuclear Armageddon.

Henry Charles Usborne [1909-1996] was a Birmingham MP, politician, lobbyist, and activist for the goal of world peace and international federation. Coming later in life to live and retire in Evesham, Usborne’s large accumulation of personal papers were deposited with the Worcestershire County Record Office in 1994. A fairly sizable collection, Henry Usborne’s records provide an excellent and rare insight into a political movement which has today faded from former prominence – the quest to found a world government, otherwise referred to as global federalism.

A fascinating character, we have written about Henry before here. With newly processed records, however, this blog reveals a little bit about who Henry Usborne was, what his ideas were, and the records he left behind.

“I am not really a politician but an engineer”, Henry Usborne declared to the House of Commons, in November of 1946. Long-standing managing director of Nu-Way heating equipment manufacturer, but also Member of Parliament for Acocks Green, Birmingham (in the Parliamentary Constituency now known as Yardley), Usborne described himself to be far more at comfort examining a blueprint than a white paper. He went on to the request from the House:

Might I make one plea to His Majesty’s Ministers? It would be this, that they should continue ceaselessly to stress on every possible occasion that it is their desire to see effective world government, elected by the people, ultimately created.

The world still reeling from the annihilation that was the Second World War, “just and lasting peace” could be secured, Henry believed, “if the Ministers who speak for Britain leave no doubt that they too believe world government can be and is being achieved”.

Henry Usborne was many things to many people, but the recently processed deposit 705:731 BA12246 is a testament to his ardent belief in global peace and implementing a world government or global federalism to achieve it.

Global federalism is a political ideology essentially rooted in the goal of achieving a global representative and democratic government which would preside over all the Earth’s nations. By common consent, and with elected representatives from each member nation, the world government would have precedence over any other national government or ruling body and would be the chief democratic institution the world over.

Though touted previously by British figures such as Lord Lothian and Lionel Curtis, the movement as Henry Usborne would immerse himself in had its roots in the late 1930s. Seen as a solution to World War Two and furthermore, as a preventative to all conflict, it became increasingly popular amongst politicians, bureaucrats and intelligentsia as the war dragged on and eventually ended.

The idea of world government as a tool of peace is explained relatively clearly by Usborne himself, in an essay entitled ‘My interests’ from July 1945, three weeks after Henry’s successful election as MP for his Birmingham constituency. In what was likely an appeal to his constituents, Usborne prefaced that:

For the last ten years I have read every book and pamphlet on international politics I could lay my hands on in an effort to discover the causes of war and what actions it is necessary for us to take to make peace permanent. I believe I know the answers, the essential ones.

In his essay, Usborne lays out his beliefs to the electorate and his proposals to achieve a global and lasting peace. The second of his points is the most pertinent, as it would seem to have remained a core tenet of his outlook for the duration of his life:

It must be recognised that the world will never enjoy permanent peace till it is governed by international law, made and can be alterable by an international legislature, supported by a judiciary and by force to interpret [sic] and to enforce its laws. The price of peace is, in fact, national sovereignty; the sooner we are ready to pay that price the better for mankind.

At this time Usborne believed in, or wished to construct, a “United Socialist States of Europe”, an idea which he would later roll back to predict only a United States of Europe.

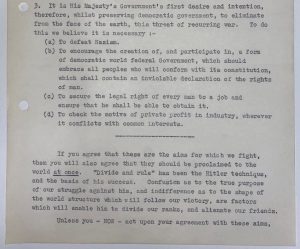

The ways with which Usborne entwined World Federalism with British socialism, however, are evident from his early material and not least from how he used his Labour Party platform to advance the objectives of global federalism. Works from as early as 1940 not only convey Usborne’s sincere belief in an eventual federation of nations, but reveal his dual prioritisation with the post-war British left’s objectives of such things as full employment and industrial regulation. In an unpublished 1940 essay, titled ‘What Price Victory?’ [sic], Usborne penned:

Usborne’s beliefs would only be entrenched in the aftermath of the Second World War, and in the wake of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Opening his Maiden Speech to Parliament in November 1945, Henry impressed upon the House the urgency with which his goals must be realised:

I believe that there is only one hope of permanent peace, and that it lies in world government. Until we have world government, as distinct from world leagues or confederations, we cannot guarantee world peace; but I do not believe that it will be easy to get world government in the compass of the time that is available to us before the atom bomb gets loose.

[…]

Is the proposal fantastic? Is it Utopian? Yes, it is both fantastic and Utopian. It is just as fantastic as the atomic age in which we now live; it is just as Utopian as the hope of world peace.

From his earlier writings, it is apparent that Henry initially perceived federalism and federal unionism as an inherently socialist objective and as part-and-parcel with a post-war socialist Britain. However, over the wide breadth of Usborne’s records, it would seem that it would be peace, or more specifically, the threat of nuclear annihilation, which would be the key guiding force of Usborne’s political objectives.

World Federalism is a political philosophy overall predicated on the notion that at all warfare and conflict is rooted in territorial and competitive nation states which vie against one another. Particularly in the emergent Cold War and the age of nuclear weapons, Usborne ultimately believed that only through a supranational and supreme global government could international peace be ensured. This extended even as far as the revocation of national sovereignty and military arsenals. In one 1956 letter to the Editor of the Manchester Guardian, Usborne wrote:

Nations rightly insist on their security. But no amount of disarmament can give that to them. Throughout these ten years of discussions have any of the governments ever proposed not disarmament, but transfer of armaments, existing or in future production, to a control organ or world instrument which would then have power effectively to guarantee security and national disarmament?

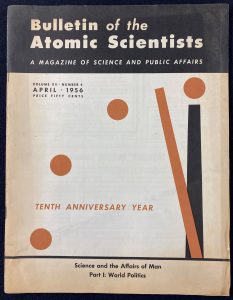

Usborne’s ideas were fixated on the topic of peace and war, from correspondence discussing atomic warfare to pamphlets on nuclear disarmament, and not least including an extensive run of editions from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – partly famous for their publication of the ‘Doomsday Clock’.

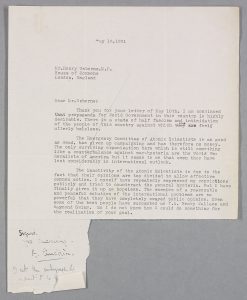

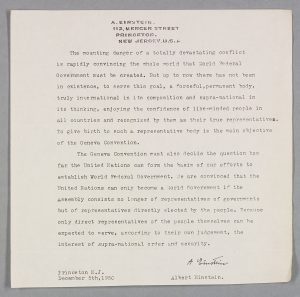

The subject was broached at least once in the correspondence WAAS holds between Henry Usborne and iconic German physicist Albert Einstein. In letters to Usborne dated May and November 1951, Einstein laments on the “mounting danger of a totally devastating conflict”, and shares his likeminded desire for a World Government as a means to prevent it. In the first of these, Einstein regrets the long demise of nuclear arsenal abolitionist group, The Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, whilst his second letter is only marginally more optimistic about the realism of his and Usborne’s shared goal.

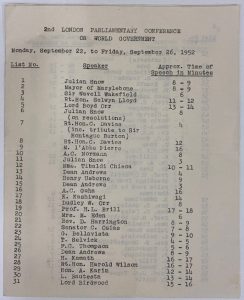

[Bottom reads: Signed, Yrs Sincerely, A. Einstein. I cut the autograph off & sent it to B[…]] Usborne’s political career – both in and out of parliament – was both extensive and international in nature, and so the correspondence and ephemera found in 705:731 BA12246 has roots from across the globe and spans five and a half decadesThe notion of world peace was certainly not an unpopular one in the immediate fallout of World War Two, and as one program of speeches from the 1952 London Parliamentary Conference on World Government demonstrates, the list of interested parties and politicians was long:

By the end of the 1950s the World Federalist Movement had reached a peak it would not return to, though Usborne would appear to have remained a key, if understated figure; passionate in its development and in continuing the cause. His records reveal an extraordinary sample of correspondence, busy maintaining an expansive network of federalist colleagues, pacifists, diplomats and politicians throughout the height of the movement and beyond.

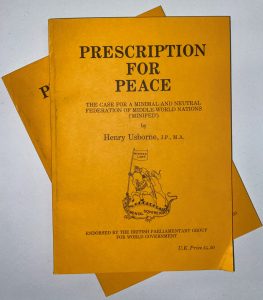

Usborne’s ardent belief in peace, and in some sort of supranational federal utility to achieve it, seems to have remained unshakeable. His parliamentary career concluded with the 1959 General Election, ousted by Conservative representative Leonard Cleaver. Finding Number: b705:731 BA12246/10/9 is full of condolences for his loss of seat. Yet his work towards world government continued with passion. By 1967 at the very least, Usborne was looking to a more pragmatic theory of international federation. In the midst of the Cold War, and believing that national sovereignty was unlikely to ever be sacrificed by the USA or the USSR, Usborne developed a new political theory which would remain his most consistently touted until his death. This was ‘Minifed’, or the “Minimal Federation of the Middle World.” In a letter from 1967, Usborne laid out his theory to a friend:

These last few years I have been working on a book in which I’m trying to explain what I now believe to be the right way to construct a system of world peace. It involves accepting the view that there are already in existence three partly completed world-states, viz (in chronological order of creation) China, USA and the USSR. For various historical reasons none of these three integral systems – they aren’t nation states – has been able to complete its destiny; that is, to become universal; and the competition between them to do so is the present cold-war.

I believe we have now to create yet another world-integrating system; to ‘federate’ all those nations that won’t or can’t be included in any of these existing systems. I call this the “Minimal Federation of the Middle World”: MiniFed for short. Then there will be four; China, Russia, America and MiniFed. These will then have to accept that they are the four governed regions of the world – and come to terms with one another.

A balancing of global power, rather than a disarming of it, Usborne saw a path to peace by creating states so powerful that a stalemate must occur and war would always be too costly an endeavour. Amongst a number of publications and articles over the years, Usborne would eventually publish Prescription for Peace: The Case for a Minimal and Neutral Federation of Middle-World Nations (‘Minifed’) in 1985, a 120-page treatise on his ideas.

Usborne’s collection makes for a fascinating insight into the mind of not only a man, but a post-war movement. So much Cold War social history is absorbed by nuclear anxieties and the fear of Mutually Assured Destruction. Henry Usborne’s papers – consisting of thousands of items of correspondence, and several hundred political pamphlets and publications – represent the efforts of some who believed they saw a path out; and above all else, show a man who was utterly committed to that end for a lifetime.

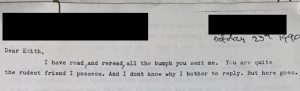

This deposit also contains what is possibly the best opening line to a letter I have ever read:

Deposit 705:731 BA12246 has now been catalogued and will shortly be available to view on our online catalogue. Please note some files have been restricted for data protection purposes.This blog was written by Tom Poole, Trainee Archivist

Post a Comment