Nine Months as a Trainee Archivist

- 10th June 2022

This week marks the last of my archivist traineeship with Worcestershire Archive & Archaeology Service. For the last nine months, the archive team have taken me on as a Trainee Archivist – training me up in all the key aspects of what makes an archive function, and allowed me to discover why archives function, the world over.

I have catalogued, conserved, preserved, constructed, and considered a whole manner of things, courtesy of my employers, and the last nine months have been excellent. I will be going on to undertake a Masters postgraduate degree in Archives and Records Management with Aberystwyth University, part-time and via distance-learning, so that I can continue to work in the field, doing work that I love and refining my professional skills in a practical environment.

For those who are unaware, there are a handful of routes into the archival profession, but undergoing a traineeship with an institution is one of the more well-trodden, and one which I have learned some of my colleagues also walked. Trainees might undergo their initial training for a few months, or a year, and then those who want to continue will often enrol with one of the six universities in the British Isles (including University College Dublin) to offer an ARA-accredited postgraduate course. Currently, it is only after graduating from one of these courses can someone be considered, professionally, an ‘Archivist’, though there are other avenues opening up. Not unlike an apprenticeship, the purpose of traineeships in archives is to provide novices with hands-on experience and on-the-job training, able to develop professionally whilst (hopefully) benefitting the institution at the same time with their work.

For a young graduate like myself, it was also the perfect opportunity to dip my toe into the world of archives, records management, and professional heritage. It seemed incredibly interesting, something I thought I could be good at, I needn’t commit to a postgraduate course until I’d tried it first, it was offered as paid, and it was a commutable distance from home. My previous experience had been as a receptionist with the NHS, but I also graduated university with a degree in History and so naturally, the love for the past and for original sources was already there.

I applied, interviewed, and miraculously got the job, and spent my month’s notice reading Arlette Farge’s The Allure of the Archives and Carolyn Steedman’s Dust. I now know those books aren’t really about archives as much as they are about history and historians, but I would still wholeheartedly recommend them to anyone who would be reading this blog post.

Minute book used by the Coventry Charity of Droitwich, used all the way through from their conception in 1686

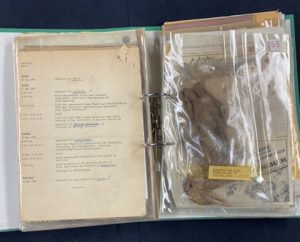

Letters, 1944, and posthumous material of Hedley Noel Beadle, WWII serviceman with 67th Field Regiment R.A. WAAS holds the last letter that Beadle is known to have sent home.

My first direct contact with an archivist before I ever worked in Worcestershire was meeting a friend of my project coordinator, when I was volunteering with Leeds Museums & Galleries at the end of 2020. She presented to our team on the skill of palaeography, something which any archivist will have to put to use at some stage, be it reading historic probate records or seventeenth century manuscripts. I have since completely forgotten her name ( – sorry!), but what I can vividly recall was the skills and the work she introduced me to, and the complete passion for her job with which she spoke. By the end of the seminar I remember I was still a little confused by what she actually did for work – was her entire job to just read old handwriting all day? I now know that is far from the truth but I was more than enamoured with it.

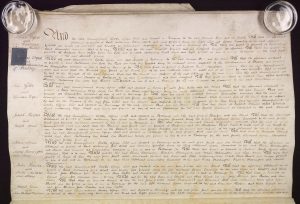

Award of Enclosure for land in Badsey. A (relatively easy) example of why being able to decipher historic handwriting can be a useful skill

“What does an archivist do?”, when family and friends ask, is a question I still struggle to answer in any succinct way without rambling on. This is because archive workers (Archivists, archive assistants, digital archivists, conservators, etc) can end up doing a lot. They focus not only on preserving the records of the past, but making those records as accessible as possible: be it making them strong enough to be touched by human hands, photographing them to reduce the risk of damaging them, constructing a legible method of finding them amongst hundreds of thousands of similar-looking pieces of paper, or fetching them from the strongrooms so that members of the public can view them.

What makes it difficult to explain, is one reason why I love it, because the long and short of the field is that archivists preserve public and private information, though the day-to-day of what that entails can be incredibly varied and can rapidly change.

Tom the Burlingham Bird, as he was found.

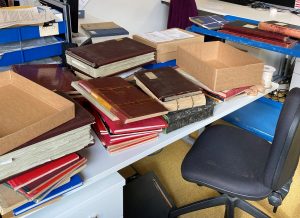

Since starting, the team has put me to work on a whole host of tasks, getting involved with what goes into the day-to-day running, as well as the wider strategy, of archival institutions. I’ve spent a lot of time working on the archive’s backlog, learning how to catalogue, and all the processes that go into the collecting, care, and organising of historic records. My first, and still incredibly memorable, catalogued accession was the travelogue of Worcestershire woman Eliza Jane Molineux. Since then, from mummified birds to machinegun instruction manuals, I’ve had the chance to examine, process, and care for a wide selection of WAAS’ records. I’ve had the chance to read, clean, catalogue and store the last letter known to have been sent by an artilleryman, handled maps that are hundreds of years older than me, and I’ve accidentally discovered letters from Albert Einstein.

I’ve also worked on the searchroom desk and behind our online enquiry system, resolving the typical and the atypical requests we might receive, or directing archive users to the next best thing. It’s been great getting to work in a busy searchroom in the fabulous Hive building, allowing me to understand what archive users want and what they might need.

In addition, it strikes me to mention that records in 2022 are no longer purely physical, but increasingly, and in the future, overwhelmingly, digital. Nine months ago I had never even considered that digital records needed to be preserved or that anyone would ever want to access them in the future. This ranges from considering the (surprisingly short) life-span of CDs to implications of blockchain technology for the records of tomorrow. The problems and opportunities presented by digital archives is one I’ve been entirely introduced to with WAAS, and one I now get to help tackle in some small part, aiding our digital strategy officer with the pre-ingest of digital records and the generation of metadata. This all is just some of the work that many archive professionals get involved with.

One of many of our 8” floppy disks, with a standard 3.5”. Readers for 8” have been out of manufacture for years.

The challenges have been numerous but rewarding. For one: Archives are vast. Receiving a tour of the wonderful Hive building on my first day, I thought: How much stuff can seven strongrooms really hold? It turns out the answer is a) a lot, b) immeasurably more than you think, and c), a tad more than that.

For two: Worcestershire is also vast. I’m from the West Midlands but I’m not a Worcestershire lad. Worcestershire may not be one of the larger counties of England, but with its network of civic and historic parishes, along with a deep, rich history, it felt coming in as though there was a impossible amount to learn about the geography and civic network of the county.

Nursing records, during the cataloguing process. Due to personal data contained within, some of these records are closed to public access until 2072.

My position here has been kindly funded by the Friends of Worcestershire Archives, to whom I am immensely grateful for the opportunity they have afforded me. They are currently looking for new members! My position has also been enriched by my colleagues who have assisted me, educated me, and been incredibly patient with my incessant questions.

Practical experience is highly valued in archives and heritage, but quality experience is hard to come by – and I can undoubtedly say that WAAS has provided me with the best experience. I would advise others who are thinking about joining the sector to just go for it and apply for traineeships that present themselves. My time with WAAS has given me a strong foundation from which I can hopefully spring a successful career in archives and records.

Tom Poole, Trainee Archivist

Post a Comment