Beoley’s Big Dig

- 24th February 2023

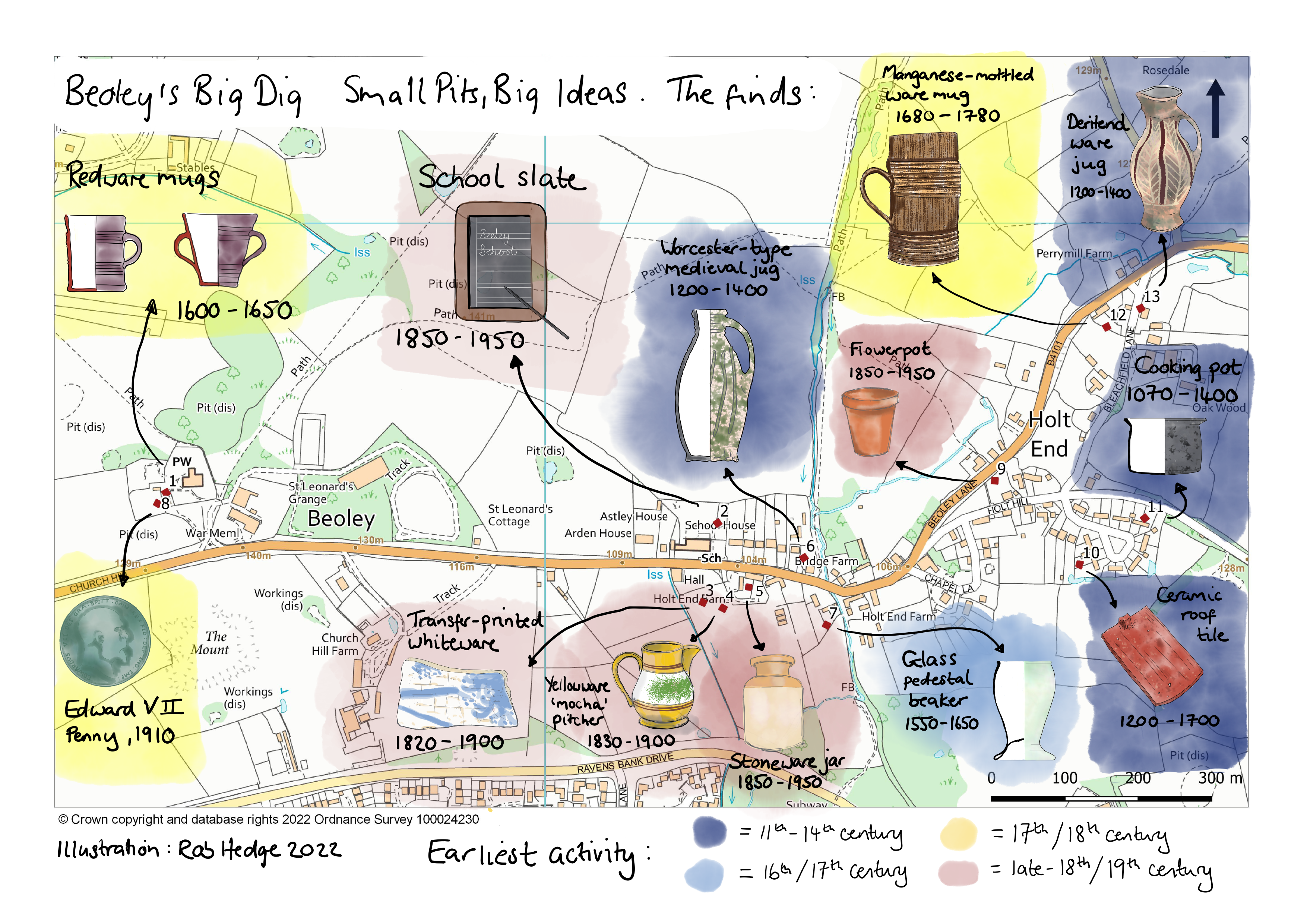

In autumn 2021, 13 test pits were excavated across Holt End village in Beoley, Worcestershire. This community excavation was part of a wider project – Small Pits, Big Ideas – researching rural medieval settlements across the county. Together, these test pits tell a broader story of the village over time.

Today our household rubbish is taken away regularly, but in the past rubbish was often thrown out the back of houses. This wasn’t just food waste, but broken pots, bits of building rubble and anything else that was old or broken. Back gardens are therefore an ideal place to look for clues. Pottery can be easily dated, as fashions for different styles changed over time. The amount of pottery found in a test pit can give us a rough idea of how nearby people lived at different times in the past.

Map of Beoley showing key finds and earliest settlement activity in each test pit

What is a test pit?

Test pits are mini excavation areas, just 1m by 1m. They are dug in 10cm layers (called ‘spits’) with the finds from each spit kept separately, so that it’s known how deep down they were found. Test pits were mostly excavated down to the ‘natural’, which is the point at which archaeology stops and undisturbed geology begins. The depth of the Bewdley test pits varied quite widely, ranging from 0.3m – 1.4m below ground level.

So, what did we find?

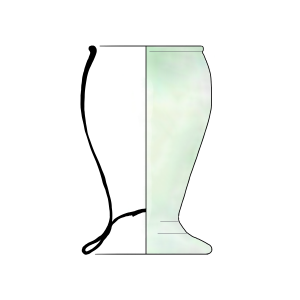

Firstly, it’s important to say that the majority of Beoley’s test pits reached the natural geology, meaning that all archaeological layers was excavated and the oldest clues weren’t missed. Finds were mostly typical of household waste and general building rubble. Notable exceptions include an early (1550 – 1650) glass goblet fragment, possible piece of burnt daub from a timber framed building and smithing waste from working metal. Whilst the glass is an unexpectedly high status and rare find, potentially from Beoley manor, the smithing waste is a reminder that rural settlements involved many more trades than farming.

Holding some finds

Where was the medieval village?

Surprisingly little medieval pottery was found. If Beoley village (also called Holt End) had been a medieval village centred around a green or spread along a road then more test pits would have been expected to produce medieval pottery. Instead, medieval activity was found in three spread out locations – alongside the brook and an old holloway (Test Pit 6), within the moated platform (Test Pits 10 and 11) and at the end of Bleachfield Lane (Test Pit 13). From this evidence, it appears that medieval Beoley was small clusters of houses and farms spread out over a wide area rather than a concentrated village. Dispersed medieval settlements are often, but not always, found in wooded areas – the early medieval Domesday survey records a large area of woodland within the parish, so it’s interesting that this may have also been the case in Beoley.

Checking carefully for finds

Why is the medieval church separate from the village?

Medieval churches were typically alongside villages, so where they stand alone today it is usually due to the settlement gradually shifting over time or being total abandoned. St Leonard’s church is just such an example, as it sits at the top of the hill whilst the modern village is further east.

However, no medieval pottery was found near to the church (Test Pits 1 and 8) and test pits at the base of Church Hill (Test Pits 2-5) don’t contain evidence of a medieval settlement shifting down the slope over time either. There may well have been medieval or earlier dwellings on top of Church Hill that were too far from the test pits to be detected. Yet regardless of whether or not there were houses on the hilltop, it seems likely that there wasn’t an obvious settlement centre by which to build the church. This raises the intriguing possibility that St Leonard’s church may be older than its 12th century masonry and have Saxon origins. Alternatively, in the absence of an early medieval village centre, other factors may have had a greater influence on the church’s location, including the medieval belief that being higher up could bring you closer to the heavens.

Glass goblet fragment from test pit 7 |

An illustration of what the complete goblet would have looked like. (Rob Hedge 2022) |

Where was the medieval manor?

Test Pits 10 and 11 both produced medieval pottery, which is the first – tentative – confirmation that the square earthwork under Moss Lane Close is a medieval moat and may have been the site of Beoley’s manor for a time.

Moats take considerable effort, and therefore money, to create so were generally only built around high status buildings, such as manor houses and hunting lodges. It is therefore likely that Beoley manor once stood on what is now Moss Lane Close, at least for some of its time. The 16th century writer Habington describes Beoley manor as “a Lordshyp in former ages, fortified with a Castell”, whilst the 18th century historian Nash claims that the Beauchamp’s seat at Beoley burnt down in 1303.

Several locations have been suggested for the site of Beoley’s medieval manor: The Mount earthworks south of St Leonard’s church, moat around Moss Lane Close and underneath Beoley Hall. The Mount has not been excavated and if a moat did exist at Beoley Hall it has been lost during construction of the 18th century hall. It is tempting to fit the medieval roof tiles, pottery and burnt daub found in Test Pits 10 and 11 to the tale of Beoley manor burning down in 1303. A fire many also have given the Beauchamp family the impetus to rebuild the manor elsewhere, perhaps at Beoley Hall where the manor was latterly located.

However, it’s possible that the moat at Moss Lane Close was instead a hunting lodge or other high status building. There is also mention in 1316 of a court with a grange in Beoley and it is unclear if and how The Mount fits into the history of Beoley manor. Clearly there is more of this story to be unravelled, but confirming the medieval origins of Moss Lane’s moat is a significant step forwards.

Two piece of medieval pot from test pit 11

When did the village first start to look as it does today?

There is unlikely to have been a sudden turning point when Beoley went from being dispersed clusters of houses to a nucleated village. However, from around the 17th century there was a gradual shift towards one concentrated centre. Besides an increase in pottery, several existing cottages as well as farms were built around this time. Evidence from both archaeological finds and historic buildings shows that the gaps between dwellings where slowly filled in during the 18th and 19th centuries as the village became less spread out.

Sitting in test pit 10!

Want to know more?

If you would like to find out more, check out the full report on Beoley’s Big Dig. You can also watch a talk below, which was given to the village in March 2022.

Post a Comment