Crop marks, photogrammetry & the Civil War at Hartlebury Castle

- 9th February 2023

Back in the hot weather of July 2022, with its parched brown crunchy grass, one of our Project Officers undertook a photogrammetric drone survey within the ground of Hartlebury Castle, with the kind permission of Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust. There were no particular expectations for this, beyond that parched grass can be ideal for showing cropmarks – and sometimes just having a look can really pay off.

Hartlebury Castle in July 2022

Cropmarks can occur where past features have been dug into the ground and backfilled with material that retains moisture better than the surrounding geology, resulting in comparatively lush grass in these areas. Alternatively, the opposite can happen where somebody has built a structure and reduced the ground’s moisture retention ability, leading to grass dying off more easily when stressed by heat. Both types of cropmarks can indicate the presence of archaeological features and, with the growth in heatwaves, have increasingly been in the news over the last few years.

So, it was with surprise and delight that one very noticeable cropmark appeared on high ground to the east side of the castle (above the present car park). The cropmark took the form of a very large triangle pointing east. It was at least 60m across east to west and 50m in width, north to south. Within the middle of this were areas of lighter scorched brown grass, suggesting the ground had not been dug there. To get a sense of its scale, see the images below.

Map of Hartlebury Castle with photogrammetric survey plans

Photogrammetric survey plan of the suggested bastion with red dotted line interpretation of the feature

What is this feature? How do we interpret it? A clue is perhaps in the history of Hartlebury Castle, which was occupied during the First Civil War by the Royalists. We don’t know for sure when the castle was first garrisoned, but it was likely held for a few years before falling to a Parliamentary force in May 1646. The Parliamentarians listed the provisions surrendered as: six pieces of ordinance (cannons), 200 arms, 15 barrels of powder, match and bullets proportional and “all manner of provisions for 200 men for six months at least”. History is often written by the winners and this tale is no different, as shown by Henry Townshend. He wrote that there were “provision and ammunition for 12 months” and that the surrender was “most poorly and cowardly” and occurred “without a shot” (Smith 2022). The inflation of provisions seems to confirm a substantial bias in the historical account.

Those of you who have visited were probably struck by how little the building looks like a castle and instead appears to be a large country house. This is a false impression. It is likely that a moat was dug all the way around the site with an interior wall in the 13th century. There is also record of a gate house tower, with a larger tower elsewhere on the site. The record of these buildings come from a Parliamentary survey of the site in 1647, after which it is thought they were pulled down, including the castle wall. By the end of the 17th century, little sense of the site’s military value remained with all the defences demolished and the moat largely infilled.

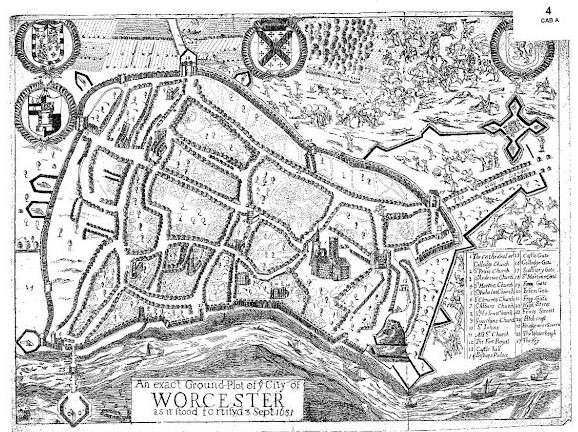

It is possible that the cropmark is a remnant of a Civil War period bastion for the placing of defensive cannon. This would turn the above account on its head. Certainly, its shape could not be much closer to the known form and size of these features – for example, see below the contemporary plan of Fort Royal on the high ground in Worcester, which had four such bastions that covered all angles. Defences of this period were earthen, to absorb cannon shot in a way that medieval stone walls simply couldn’t. For this reason, they were often constructed around the outside the existing walls, and in this case on the outside of the former moat. High ground was used wherever possible; again, this is the case here. This defensive format is known as an outworks.

Map of the city of Worcester, 3rd September 1651 (available at Worcestershire Archives reference b899:25 BA372/1)

If this feature was a bastion and part of an outworks, there will almost certainly have been at least one more. They were designed to be mutually defending, so defenders could fire back along flanking ditches at any attacking forces, with bastions in musket range of each other. It would seem most likely that any further defences would be on the south-east side of the moat garden, though this area is largely under modern tree cover, so visibility was poor when undertaking the survey. Whilst our first suggested bastion was on the high ground and dug in, it is probable that a further on the south-east corner would have had to be built up to see over the rise to the south. It is therefore possible that little remnant of this survived the post-Civil War destruction.

Do you think our eyes are being led to seeing a bastion in the cropmark? How do we find out more? Well, one of our Project Officers intends to undertake further investigations of the site, including geophysics undertaken by a local surveyor. This will hopefully verify the first bastion and shed some light on a possible second. We hope this is a start towards tying the archaeology and history together, and maybe archaeology could in the future even challenge the often repeated claim that Hartlebury Castle was surrendered “without a shot”.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust for allowing access to the site for the purposes of surveying and this blog.

References

Smith, D 2022 Most Poorly and Cowardly: Hartlebury Castle and North Worcestershire in the Civil Wars, Brewin Books

Missed part 1? Explore a 3D model of the castle and read all about photogrammetry, how it works and the (not so new) ideas that underpin it in ‘A focus on photogrammetry: Hartlebury Castle‘.

WOW ! I remember Hartlebury Castle and yes I agree it didn’t look much like a castle at the time. Thanks for sharing the history and I look forward to hearing more of your research.