Excavations at Hartlebury Castle

- 17th February 2023

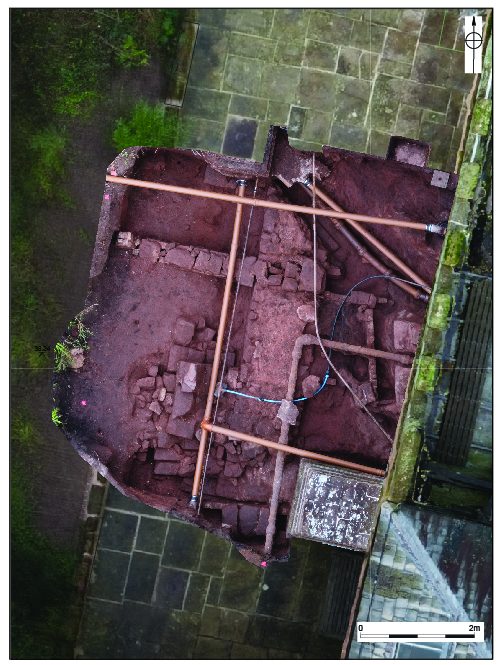

In 2022, after the identification of a possible Civil War bastion (read about this discovery in part 2 of the blog series), a small area was excavated on the west side of the castle. This was ahead of some routine maintenance work.

The area under excavation, looking east

The trench we excavated was about 6m square. When fully excavated, we cleaned up the trench as much as possible and undertook some photogrammetry – the process outlined within part 1 of this series. From this, we created the plan view and 3D model (see both below).

Photogrammetric plan of the excavation area

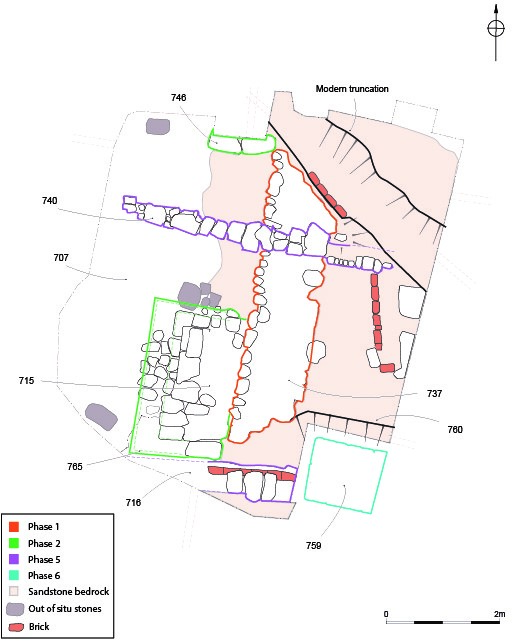

To the untrained eye, this probably looks like a confusion of walls and pipes that have accumulated over many years. But look closer and you start to see some patterns and key features, which we will highlight for you using the interpreted plan below.

Phased and interpreted plan of the excavation area

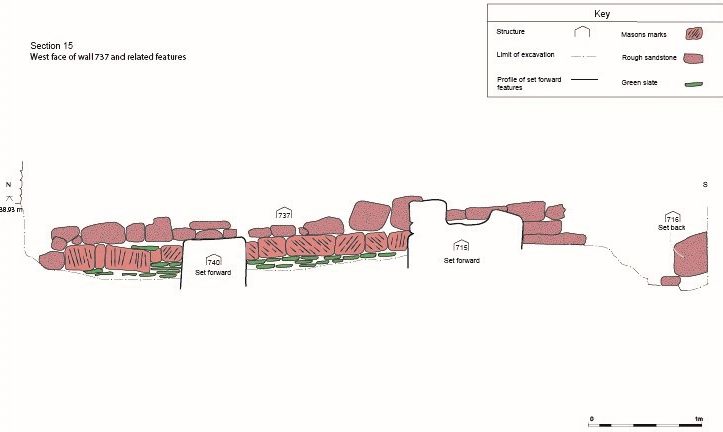

The main wall within the trench was aligned north to south, built of sandstone and at least 1.2m wide. It sat directly on top of the bedrock and had a neatly cut western face, but was much rougher and un-faced on the eastern side. Masons’ toolmarks were visible on the smoother face (see drawing below). These marks were mostly in a single direction, around 80 degrees, though there was some variation. At some point in time, two sandstone buttresses were added on the wall’s western side. These elements are the first phases (labelled 1 and 2 on the plan above) of activity seen within the excavation area.

So, what do we think this wall was part of? This is a difficult question to answer, given the limited excavation area and presence of the late 17th century wall of the castle building to the immediate east, which did not allow investigation in that direction. It may be that the eastern face of the buried wall was destroyed a long time ago and that it was used to form part of a building to the east. This seems unlikely though for a wall 1.2m wide – that’s much more substantial than needed for a building.

Perhaps the best interpretation is the simplest one: that this formed part of a wall around the boundary of the site – the original medieval curtain wall. This would certainly make sense in that the wall was located on the edge of high ground, which then dropped quickly down towards the moat to the west. This interpretation fits with the width of the wall too, which could have supported a significant height of masonry.

One issue, however, is that we do not know for sure that this wall was medieval, and we certainly cannot say (with further evidence) if it was part of the 13th century crenelations recorded to have been built by Bishop Godfrey Giffard. A key difference between this wall and other stonework at Hartlebury Castle is the toolmarks – many of the toolmarks visible elsewhere on the building are cut in two directions, as opposed to the single direction seen here. When you add in that much of the fabric of the castle buildings are 17th century in date, it does raise the probability that this wall is earlier.

West facing elevation of possible curtain wall

Further clues that this wall was the main boundary or curtain wall of the site come from surrounding deposits. Several archaeological layers butted up against or went over the wall and therefore must be later than the wall itself. These deposits contained a number of finds including tile, window glass and a clay pipe stem. Slightly frustratingly, most of the finds were not closely dateable, but one of the pipe stems had WH stamped on its base and was of a type made in Broseley, Shropshire between the years 1660 and 1680. This means that the wall predated the mid-17th century and puts us back towards the Civil War, which had ended by 1651.

As discussed in part 2 of this blog trio, we know from documentary evidence that the castle’s defences were pulled down after the Civil War, but we do not know when exactly. Certainly, a number of buildings that no longer exist were still present in a parliamentary survey of 1647, but the records beyond that are not clear. The site was garrisoned by the Parliamentarians during the later 1640s, so perhaps it was in their interest to keep some element of the defences, meaning that they were removed slightly later. It has been previously suggested that the owner of Hartlebury Castle after the Parliamentarians, Thomas Westrow, slowly dismantled the buildings and defences and sold off the materials to recoup costs. The site’s buildings largely remained in poor condition until Bishop James Fleetwood started a programme of rebuilding in the 1670s (Smith 2022), mostly leaving the building we know today.

With the continuing development of the building through the 18th century onwards, there became an increasing need for drainage and piping, which has gone a long way to visually confuse the intriguing sequence of – previously unseen – structures uncovered in 2022.

The possibilities outlined here appear to fit quite well with the known history of the site, as well as the architectural evidence of the standing building. As is often the case, small excavations like this raise tantalising possibilities and can appear to give solid conclusion. But it is wise to keep an open mind, as hard earnt archaeological knowledge tells us that that slightly shifting the location of a trench can draw surprisingly different conclusions.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to OHES Environmental Ltd for commissioning the project and to Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust for allowing access to the site for the purpose of excavation and permission for this blog.

References

Smith, D 2022 Most Poorly and Cowardly: Hartlebury Castle and North Worcestershire in the Civil Wars, Brewin Books

Missed the series?

Part 1: Explore a 3D model of the castle and read all about photogrammetry, how it works and the (not so new) ideas that underpin it in ‘A focus on photogrammetry: Hartlebury Castle’.

Part 2: Read about a possible Civil War bastion that’s remained undetected for centuries in Cropmarks, photogrammetry & the Civil War at Hartlebury Castle

Post a Comment