White Ladies Aston Big Dig

- 10th March 2023

Unexplored earthworks that look suspiciously medieval: an exciting start for any excavation! During October 2021, 8 test pits were excavated across the village of White Ladies Aston, just east of Worcester, as part of the Small Pits, Big Ideas project. These, when combined with previous community test pits in the village, reveal a story of medieval division and decline.

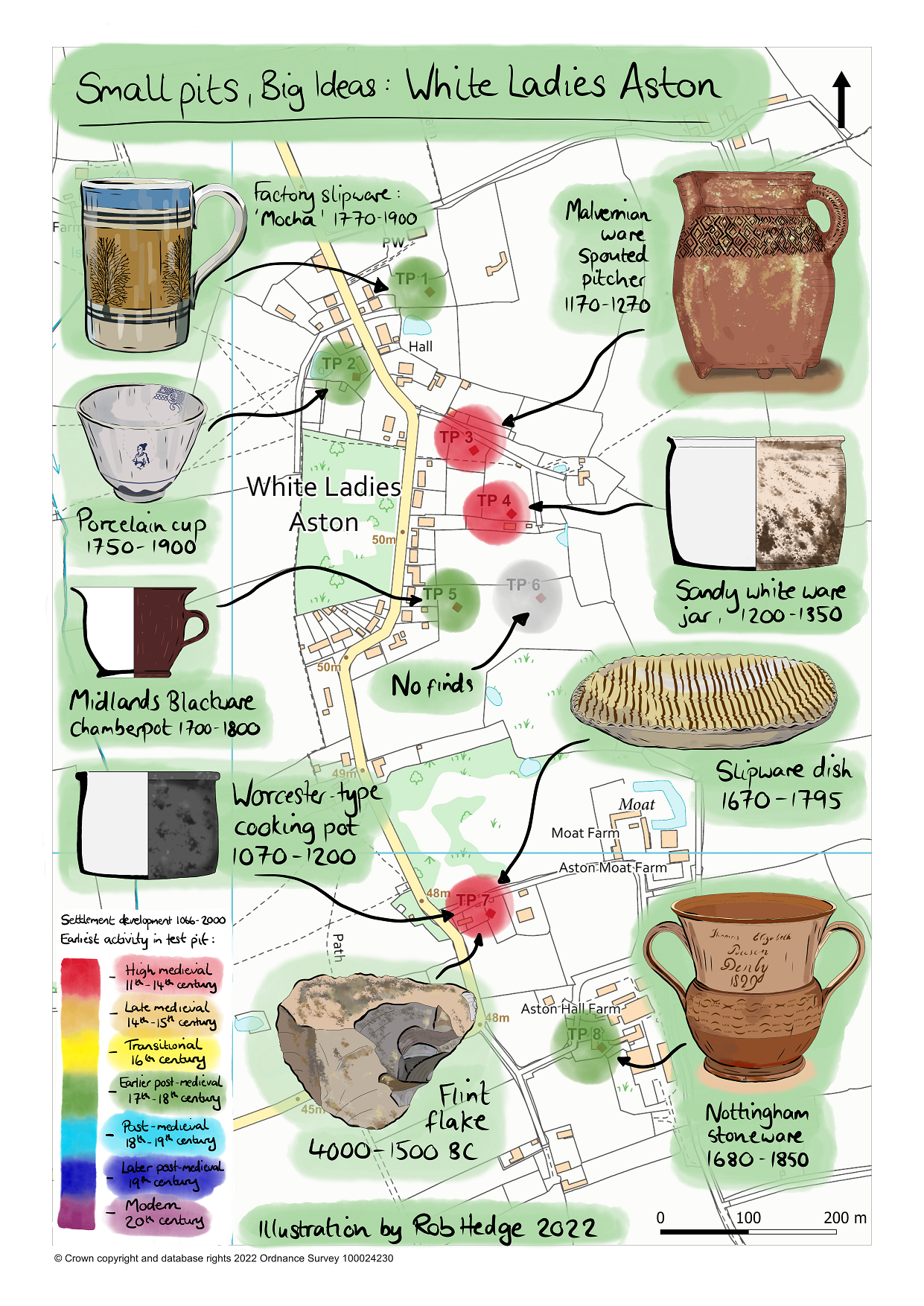

Summary of White Ladies Aston’s test pits, showing the earliest settlement activity found and a selection of finds (created by Rob Hedge)

This community excavation was part of a wider project – Small Pits, Big Ideas – researching rural medieval settlements across the county. Together, these test pits tell a broader story of the village over time. Today our household rubbish is taken away regularly, but in the past rubbish was often thrown out the back of houses. This wasn’t just food waste, but broken pots, bits of building rubble and anything else that was old or broken. Back gardens are therefore an ideal place to look for clues. Pottery can be easily dated, as fashions for different styles changed over time. The amount of pottery found in a test pit can give us a rough idea of how nearby people lived at different times in the past.

What is a test pit?

Test pits are mini excavation areas, just 1m by 1m. They are dug in 10cm layers (called ‘spits’) with the finds from each spit kept separately, so that it’s known how deep down they were found. Test pits were mostly excavated down to the ‘natural’, which is the point at which archaeology stops and undisturbed geology begins. In general, this was 40-60cm below ground level in White Ladies Aston.

A village of two halves

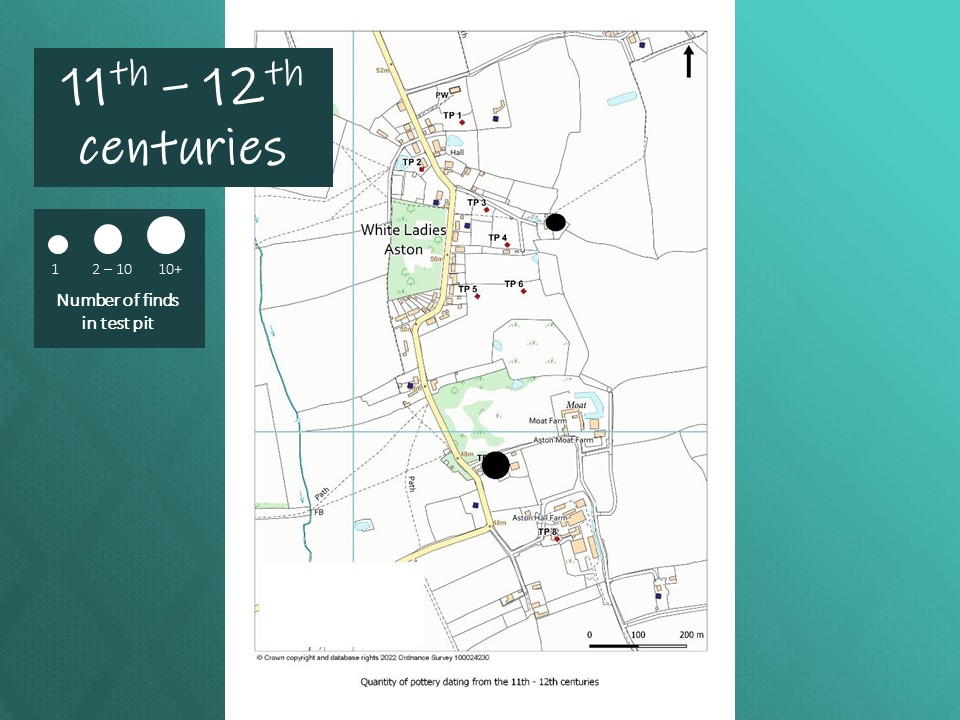

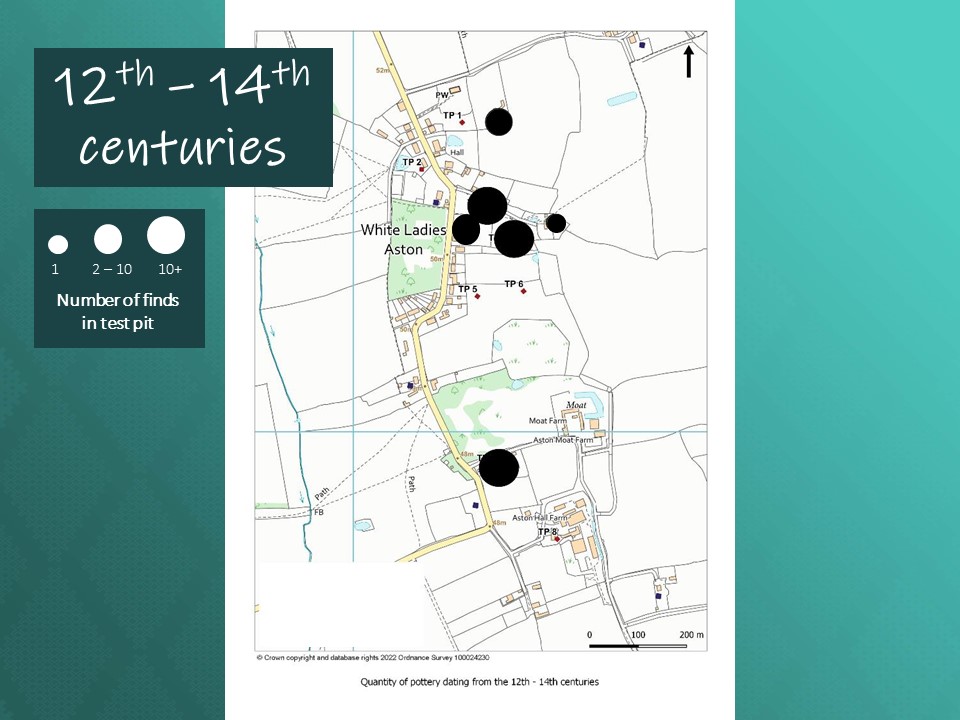

Throughout the medieval period White Ladies Aston was not a single concentrated village. Instead, there appears to have been two separate clusters of houses.

The northern settlement is likely to have formed around an older trackway, which runs southeast towards the Bow Brook. These dwellings may be a continuation of Roman and Saxon settlement slightly further to the east, although these older areas of occupation haven’t been confirmed by excavation. The earthworks across Polly’s Piece date from the 12th or 13th century and may be planned rather than ad hoc settlement. It is possible that the Bishop of Worcester – the chief landowner – was behind these changes, as the Church at this time were keen to increase rental income from their numerous manors.

Sieving through soil for finds at Test Pit 4 – Polly’s Piece

To the south, finds from the 10th – 11th century onwards have been found by Nordle Cottage in Moat Lane. This settlement cluster may have been smaller, as another test pit close by (at Aston Hall Farm) produced no medieval pottery.

Given that two clusters of settlement are emerging from the archaeological evidence, it is interesting to see that historic records also show divided land ownership. Medieval White Ladies Aston had an array of changing landlords, and as far back as the Domesday survey of 1086 two different tenant-lords held land under the Bishop of Worcester: Ordric of Croome and Urse the Sheriff.

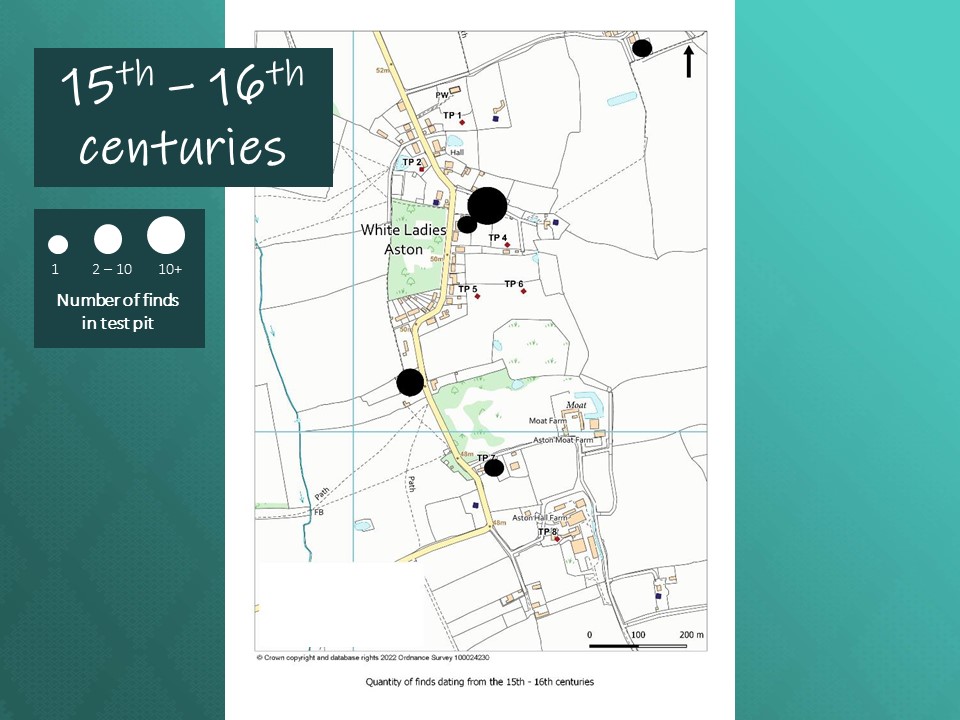

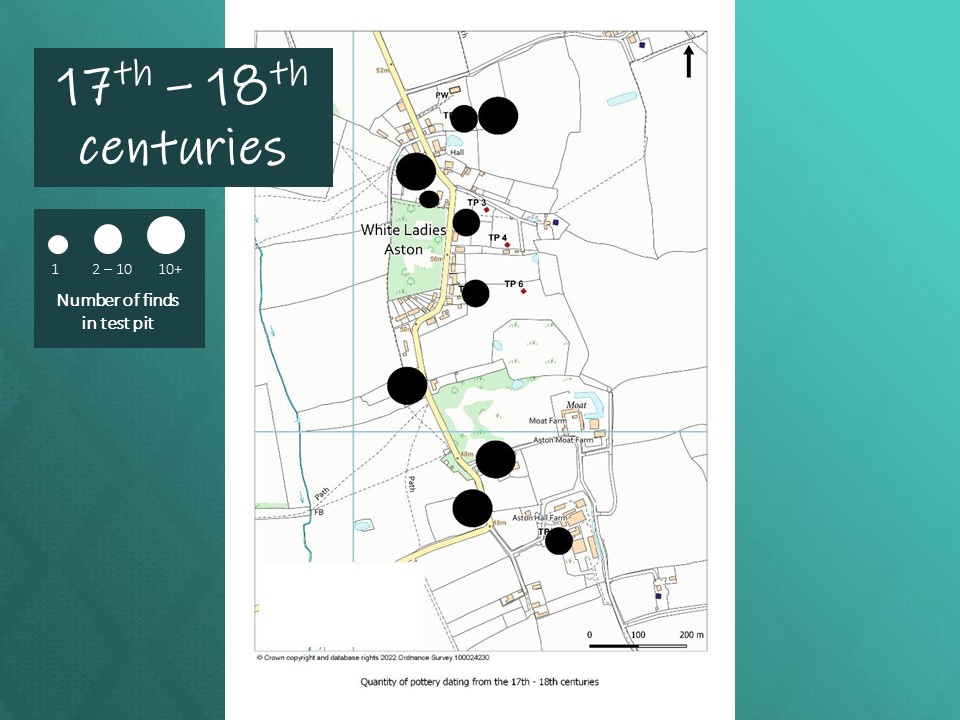

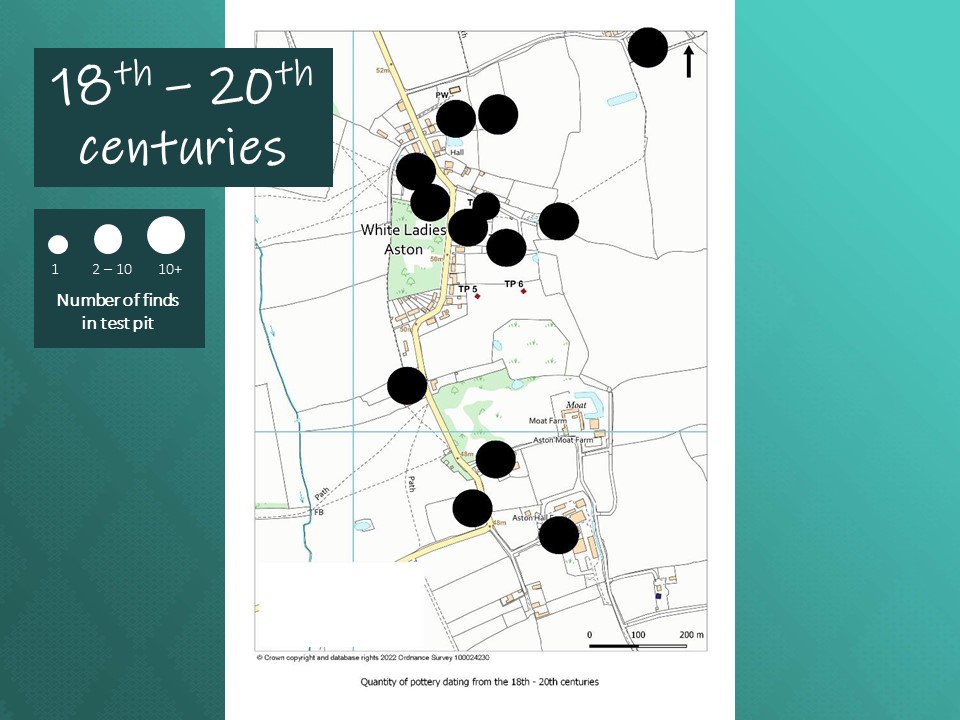

Quantity of finds by date – use the left and right arrows to scroll through the maps, or hover over the image to pause.

A tough time?

Historic documents suggest that a series of changes took place in White Ladies Aston during the 14th century. Firstly, fewer people are listed on the lay subsidies (tax lists of the day) compared to before. It is also possible that the number of major landholders in White Ladies Aston reduced during the 14th century. However, challenges with translating early records and the complex system of overlords and tenant lords makes this hard to untangle with certainty. At a national and European level, the 14th century also saw the Great Famine from 1315-17, Great Bovine Pestilence of 1319-20 and Black Death in 1348-49.

The widespread troubles of the early 14th century may account for the reduction in tax-eligible households within White Ladies Aston. The lay subsidies, which only list the heads of wealthy households, record 18 names in 1280 and only 9 in 1327. In 1332-3 it is also noted that the settlement as a whole paid under a quarter of the total tax due. Whilst the majority of Worcestershire parishes pay under half that year, only 20 of the 137 parishes pay less than a quarter. It is clear that White Ladies Aston experienced hard times before the arrival of the Black Death, although whether it shrinks in population or just prosperity is hard to tell from records alone.

Artefacts uncovered by test pitting seemingly mirror the recorded late medieval decline. Only two test pits yielded 15th – 16th century pottery and both in relatively small quantities. The majority of 12th – 14th century finds are ceramic cooking pots, which do become less available after the mid-14th century, due to households switching to longer-lasting metal versions. However, pottery does continue to be made around Malvern and only a handful of such sherds were found in the test pits, despite households having access to them.

Sherds of medieval pottery from Test Pit 7 |

Fragments of medieval pottery from test pit 3 showing the colour of the original glaze in the printed pattern. Photo credit: Glynis Dray |

At Polly’s Piece, Test Pit 3 revealed ongoing – if dwindling – occupation until the 15th or 16th century. Yet the second test pit in Polly’s Piece didn’t implying that at least some medieval house plots were abandoned either during or shortly after the 14th century. Combined with a few 15th – 16th century finds from test pits that lacked medieval activity (Sandfield Cottage and Aston Court Farm), this tentatively points towards a settlement that reduced in prosperity during the 14th century and possibly a little in population size as well. White Ladies Aston appears to have taken a while to regain its strength, but as it re-grew during the 15th and 16th centuries houses began to be built on new plots.

Modern layout

The village today runs north to south along the Evesham Road, yet test pit evidence suggests that the medieval settlement had two separate centres. So, when did the village taken on its current layout?

The beginnings of today’s linear layout can be seen in the 15th or 16th century when activity appeared in previously unoccupied areas. However, given the small quantity of artefacts from this date and relative explosion of 17th – 18th century test pit finds, it’s likely that the village’s reorientation took place towards the end of this time period.

Digging in Test Pit 7

Want to know more?

Keep an eye out for the full report on White Ladies Aston’s Big Dig, which will be available from our website soon. You can also watch a talk below, which was given to the village in July 2022, and read the 2017-18 test pit report for White Ladies Aston.

Post a Comment