Wolverley’s Big Dig

- 3rd March 2023

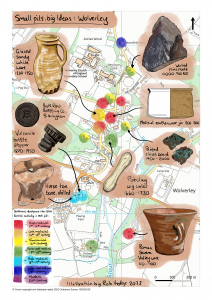

In June 2022, 15 test pits were excavated across Wolverley, Worcestershire. This community excavation was part of a wider project – Small Pits, Big Ideas – researching rural medieval settlements across the county. Together, these test pits tell a broader story of the village over time.

Today our household rubbish is taken away regularly, but in the past rubbish was often thrown out the back of houses. This wasn’t just food waste, but broken pots, bits of building rubble and anything else that was old or broken. Back gardens are therefore an ideal place to look for clues. Pottery can be easily dated, as fashions for different styles changed over time. The amount of pottery found in a test pit can give us a rough idea of how nearby people lived at different times in the past.

Map of Wolverley showing key finds and earliest settlement activity in each test pit

What is a test pit?

Test pits are mini excavation areas, just 1m by 1m. They are dug in 10cm layers (called ‘spits’) with the finds from each spit kept separately, so that it’s known how deep down they were found. Test pits were mostly excavated down to the ‘natural’, which is the point at which archaeology stops and undisturbed geology begins. In general, this was 30-70cm below ground level in Wolverley.

So, what did we find?

Several prehistoric worked flints and a sherd of Roman pottery were found. These are typical of rural landscapes in the region, reflecting a long history of settlement. Written records document a settlement at Wolverley from the 9th century onwards. Despite this, the first material evidence found within the test pits dates from the 12th century onwards. This is a similar picture to that of other Big Digs across Worcestershire, in Beoley, Wichenford, Badsey and the Bewdley area. It would seem that pottery was not widely used in rural Worcestershire households until the late 11th or 12th century, after the Norman Conquest.

Test pit 5 at Rock Hill – Photo Credit: Janet Oliver

What did the Medieval village look like?

From the 12th to 14th centuries (sometimes called the ‘high medieval’ period) there are relatively few test pit finds compared to later centuries, but they are nevertheless present. Medieval artefacts were found in a number of test pits across the village, but most significantly across a cluster of test pits close to the junction of Drakelow Lane and Blakeshall Lane.

Dating is hampered by an incomplete picture of the pottery industries and supply in the area, but there was evidently domestic settlement in parts of the parish by the 13th century. In Test Pit 5 at Rock Hill a wide range of medieval pottery was found, as well as glazed ridge tile of 13th to 16th century date. This suggests a substantial or specialised building, such a manor house, as tiled roofs in rural settlements at this time were unusual.

Medieval glazed ridge tile from Test Pit 5 |

Medieval pottery found in test pit 5 |

A notable quantity of locally produced medieval pottery was found, which has not been widely recorded or researched before. Medieval pottery from Test Pits 5 and 6 is also in markedly better condition that the pot found elsewhere and of later dates, suggesting that relatively undisturbed medieval deposits survive around Rock Hill and Frogmore House.

Interestingly, this cluster of medieval finds is along the edge of a slope and immediately east of a tithe barn, which was likely medieval in date, and a dwelling called the ‘Manor House’. It is possible that this medieval settlement was Woodhamcote – a name recorded in the Manor Court Rolls and speculated to be in this general area – although the name ‘Vroggemore’ (Frogmore) also appears in 14th century records.

The overall distribution of finds suggests that the settlement around Rock Hill is likely to have been the centre of medieval Wolverley, with smaller clusters of houses scattered across the parish, including at Wolverley Court. This sort of dispersed settlement was common in wooded areas, as Wolverley may have been. In addition to these settlement clusters, another might be expected around the church. Assuming that the present church was built directly over the medieval one, there is however little evidence of this, as no medieval activity was found south of the church around Rose Cottage.

From this small sample, the effects of the crises of the 14th century (including the Great Famine of 1315-17 and Black Death in 1348-49) are unclear, but the presence of later-medieval and transitional wares suggest settlement continuity into the late-15th/16th century and beyond.

Digging at Wolverley Court – Photo Credit: Janet Oliver

How did the village grow and change?

A large quantity of material dating to the 17th and 18th centuries was found; this is typical of rural settlements and reflects the increasing affordability of ceramic goods as much as the expansion of the settlement. By the 17th century, the village had taken on a linear layout, stretching north to south from Wolverley Church, past the brook and up the slope (along what is now Blakeshall Lane).

Across the majority of test pits, pot sherds were generally small, heavily worn and battered. This is typical of pottery that was discarded in rubbish heaps or middens, then later disturbed by gardens being dug over or field ploughed. Early 18th century white tablewares and porcelain were relatively uncommon in Wolverley compared to other Worcestershire villages, such as Wichenford. This may be due to the village’s distance from these pottery works and reduced availability of cheaper seconds. The opening of the canal through Wolverley in 1772 will undoubtedly have increased trading links and is perhaps why later 18th century ceramics were seen more widely across the test pits than pre-1760 tablewares.

The large quantities of ironworking slag across many of the test pits reflects the long heritage of industrial activity and rich natural resources of the area. It is likely that some of the material had been moved from its original production site and re-deposited. Although most was typical of smithing (iron working as opposed to production), the presence of small quantities of slag resembling that created during bloomery production could suggest nearby production sites.

Checking soil for finds – Photo Credit: Janet Oliver

Want to know more?

Keep an eye out for the full report on Wolverley’s Big Dig, which will be available to view on our website soon. You can also watch a talk below, which was given to the village in January 2023.

Wow this brings back memories of pot

washing and sorting all the sherds hoping to make up a complete pot from the sherds.