Travels in Time and through Space with Arthur Henry Whinfield

- 6th March 2024

One of the great things about my job as an Archives Assistant is that I get to review a wide range of collections, whether it’s to assist researchers in the Searchroom, to undertake cataloguing and support digital preservation or deliver physical outreach and online campaigns such as Explore Your Archive. Recently I was given the opportunity to review the 2100 glass slide collections of Arthur Henry Whinfield which were conserved, catalogued and digitised as part of the Arthur Henry Whinfield centenary project completed in 2019. Funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, the aim was to preserve and improve digital accessibility of the slides donated to the Worcester Diocesan Church House Trust by Arthur Henry Whinfield’s widow, Laura Jane Curtler, in March 1918.

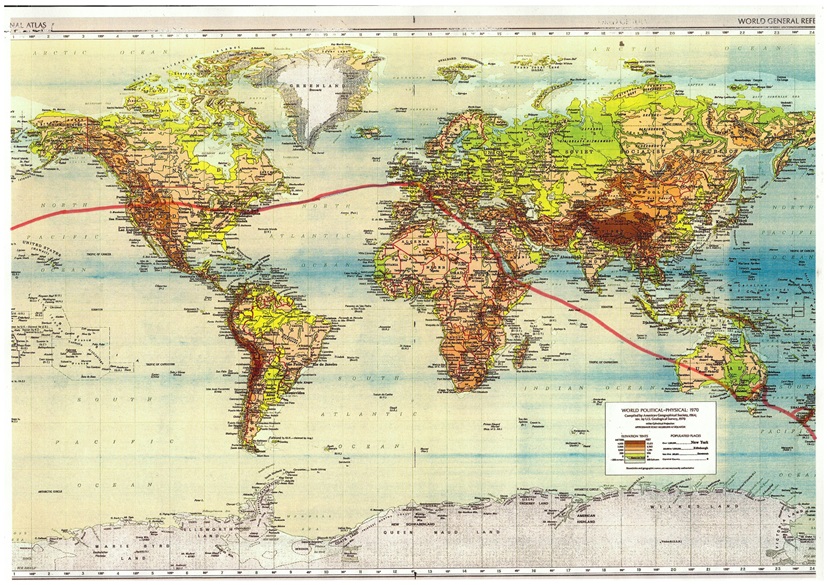

Map of Whinfield’s World Tour

Around the World in Eighty Minutes

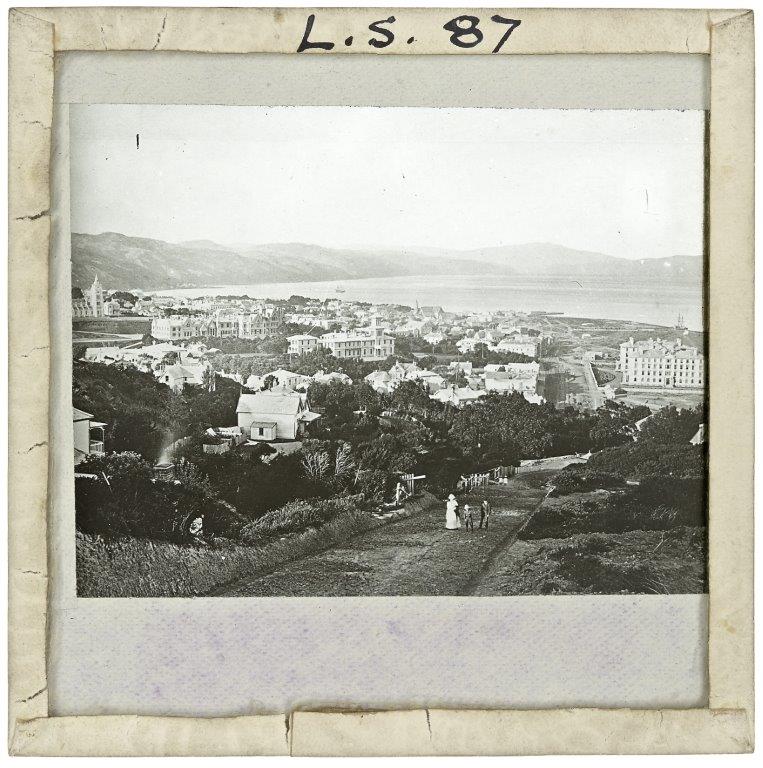

Arthur Whinfield did something truly remarkable: he travelled across the globe producing glass plate photographs of internationally important sites and landscapes during the 1880’s. Some of the places photographed no longer exist and it was a time when travel to far reaches of the world took months, was physically and mentally demanding and means of travel were pretty precarious to say the least. As I looked through various photographs of well-known sites such as New York and Niagra Falls, I stumbled upon an image that I thought I recognised – Wellington, New Zealand, but it looked so different and yet it was definitely the same place.

Wellington, New Zealand taken by A.H. Whinfield c.1880’s (looking left out into Wellington Bay) Finding No: 832 BA16072.143 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

Whinfield describes Wellington in his lecture notes from his world tour as having ‘a beautiful climate, rather warmer and rather drier than our own, and there is scenery of all kinds much like, if on a rather smaller scale, to Swiss or Italian scenery’.

Wellington, New Zealand c.2012 (view towards Lambton Quay and Wellington Bay) – Taken from the Botanic Gardens, close to the location of Whinfield’s photograph and reached by Wellington’s popular Cable Car © Anthony Roach

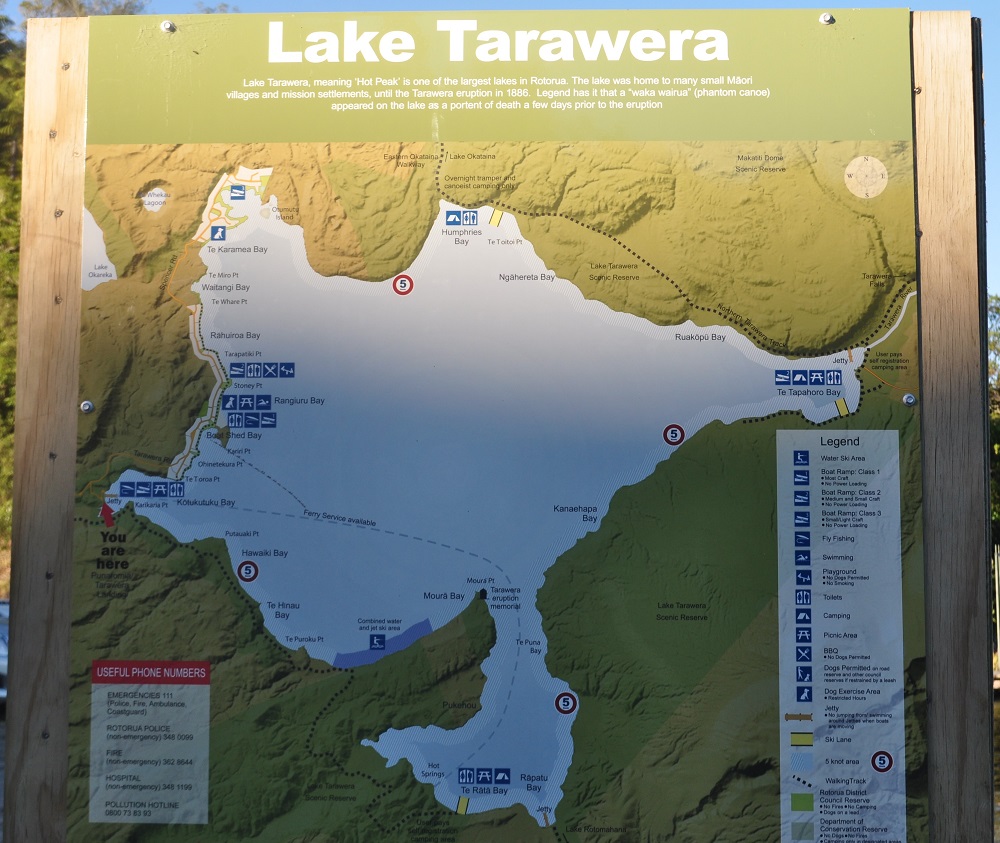

In 2012, I interned at both Auckland War Memorial Museum and Te Papa Tongarewa National Museums. Later I was fortunate to be offered a job as a Support Officer for the Forestry and Land Operations department. By chance, this involved a trip via Rotorua and Whakatane to Lake Tarawera, where Whinfield had set foot all those years ago.

The thing I remember most about the site of Lake Tarawera (spelt Tarewera by Whinfield) was the quiet serenity of the place. The lake was huge and clothed with forest and tree ferns, with a shingle shore. There were signs for a ‘buried village’ which of course immediately caught my attention. I asked colleagues what had happened and they revealed the story of a catastrophic volcanic eruption which buried a village in 1886 and one of the 8th Wonders of the World and New Zealand’s biggest tourist attraction.

White Terraces, near Rotorua, New Zealand. These were destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 1886 Charles Bloomfield (Source: Public Domain)

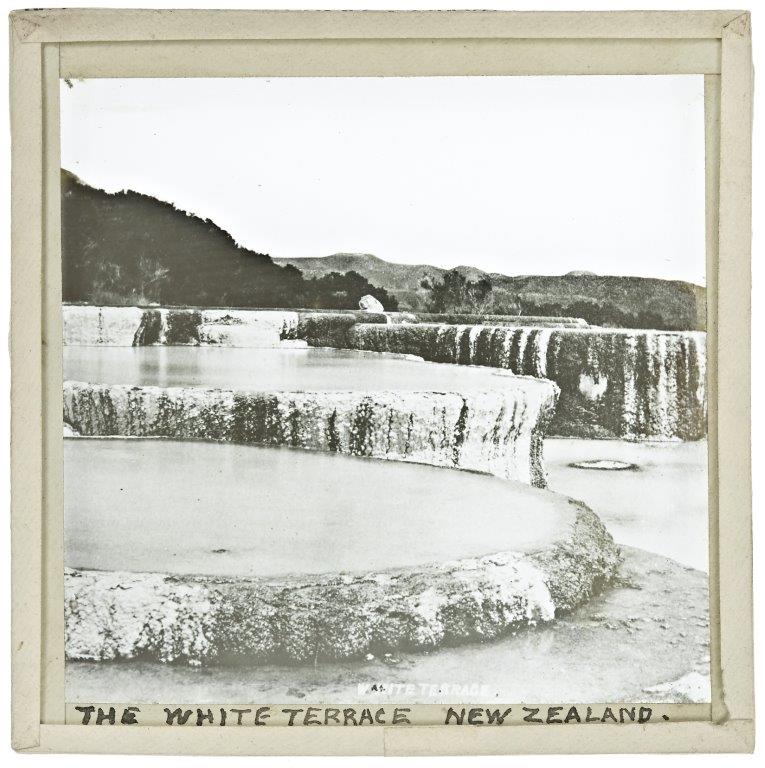

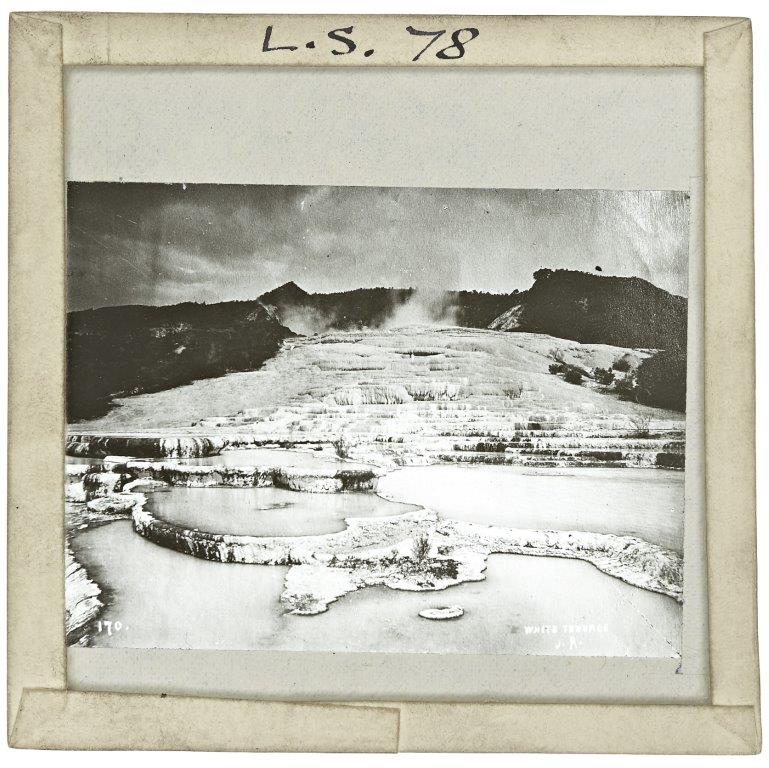

The Pink and White Terraces of Rotohamana

Whilst New Zealand in the 19th century wasn’t the easiest place to get to, one of its most celebrated wonders were The Pink and White Terraces which the Māori called Te Otukapuarangi, which means ‘the Fountain of the Clouded Sky’. The Pink and White Terraces were formed by upwelling geothermal springs. There are many geothermal sites across New Zealand and the most well-known are nearby Rotorua and Hanmer Springs. Whilst Whinfield took many of the photographs in his slide collection, he also bought commercially available slides and made copies from them or from publications – this seems to have been the case for several Pink and White Terraces images.

White Terrace, Circular Terraces by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/148 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

White Terrace, and Lake Rotomahana by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/150 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

The terraces are created by silica rich chloride water whilst the pink appearance is the result of antimony and arsenic sulphides. In Whinfield’s lecture notes he says of the terraces:

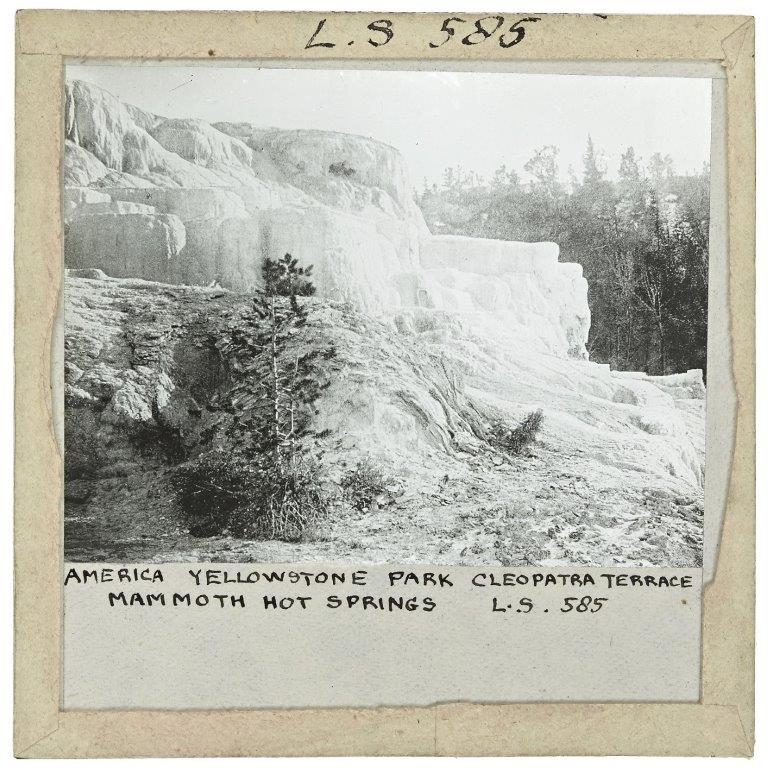

“Here we are at the famous terraces and this view of the pink terrace shows that the principle of these terraces is identical with those of the American example I showed you earlier” which was taken at Yellowstone National Park in North America.

Photograph of Cleopatra Terrace, Mammoth Hot Springs A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/137 Yellowstone Park courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

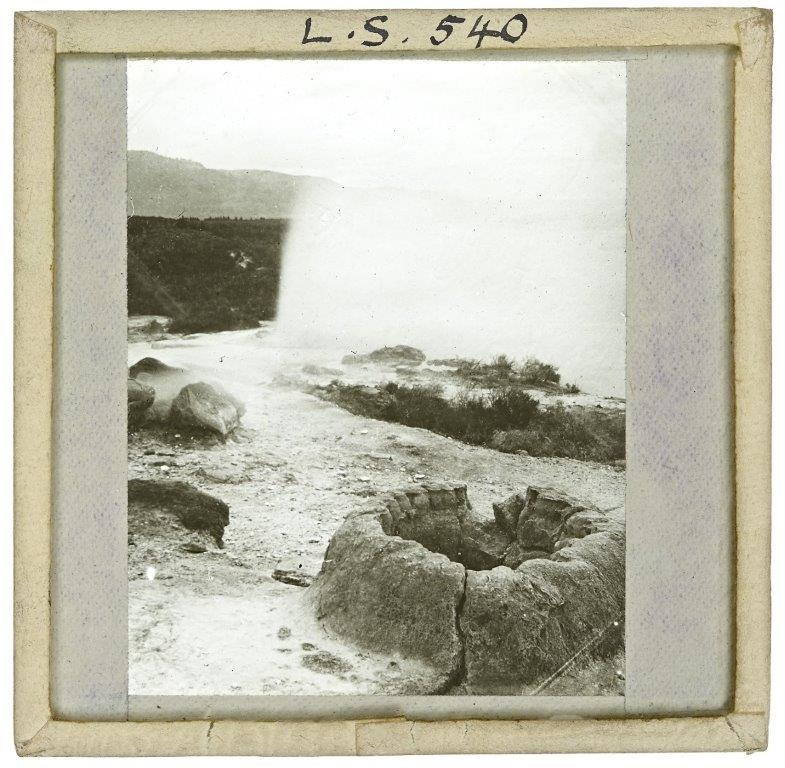

Whinfield in his notes refers to “two geysers or hot springs, one of which is active and the other quiescent” shown below. With Rotorua being an active geothermal hotspot, geysers were and still are a regular feature and the town itself has a characteristic rotten egg smell which residents just don’t seem to notice after a while, but visitors like me couldn’t really get used to it! One of the most well-known hot springs is WAI-O-TAPU, which includes the amazing Lady Knox Geyser.

Lady Knox Geyser, WAI-O-TAPU Thermal Wonderland, Rotorua © Anthony Roach

Extinct and Working Geysers by A.H. Whinfield Finding No 832 BA16072.156 The Diocesan Church Trust

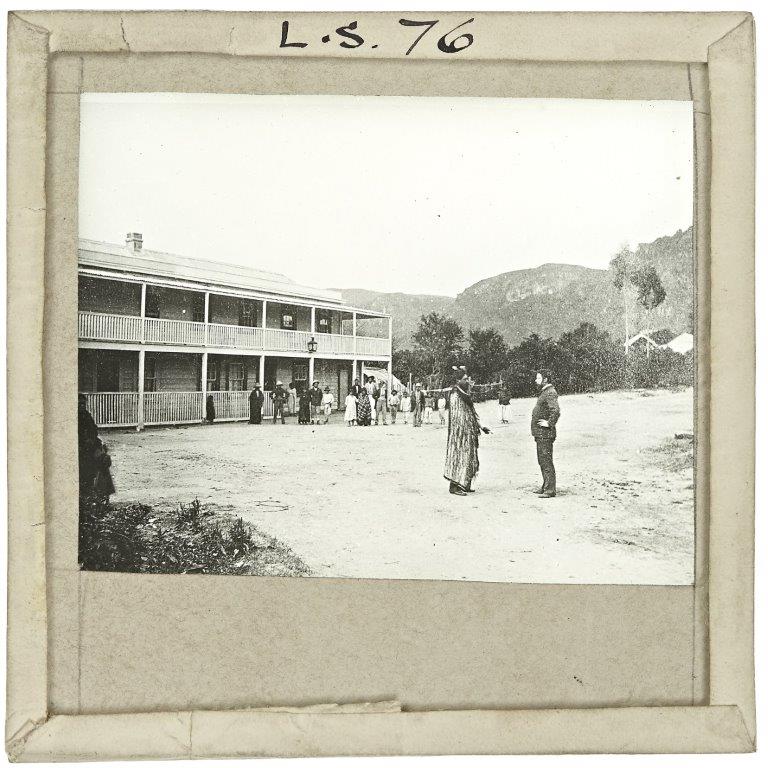

Whinfield then displays an image of the Rotomahana Hotel before the earthquake and discusses the devastation of the buried village by saying that: “We now come to the period when all this district of the terraces was devastated. Up to June 10th 1886 the country was a great resort for tourists who came to see the beautiful terraces. On that day a fearful earthquake took place.”

Rotomahana Hotel, New Zealand before Earthquake by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/153 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

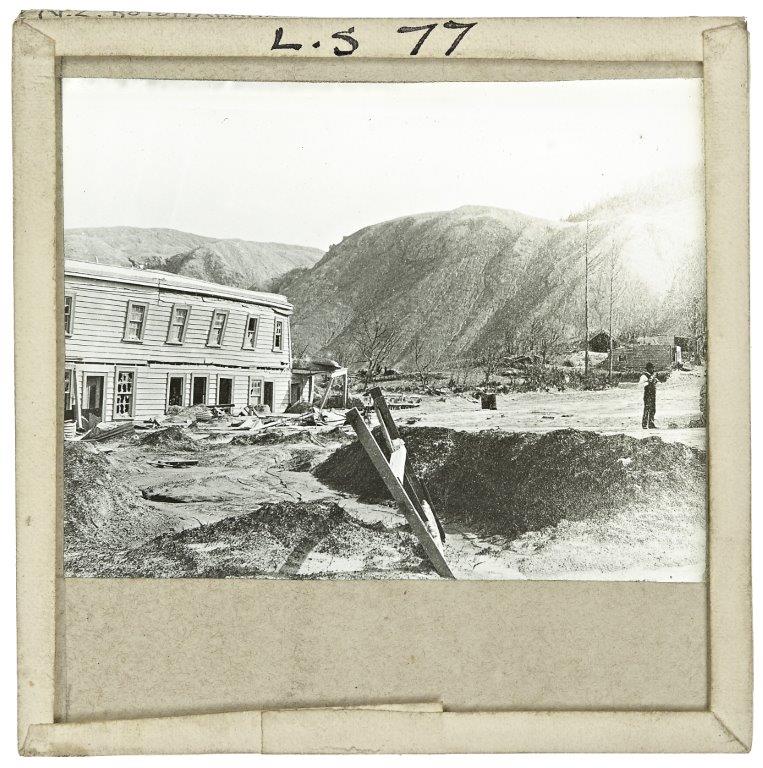

Whinfield’s next view shows the remains of the hotel, fractured, ruined and half-buried following the result of the devastation as he explains how the Lake Tarawera earthquake “threw up an enormous quantity of hot water and mud and buried the entire district including the terraces, to say nothing of a Maori village Te Wairoa of which most of the inhabitants perished. The countryside has been so entirely altered in appearance that it is by no means certain where the terraces are now, but it is some satisfaction to know that it is believed that new ones are coming into existence elsewhere…”

Rotomahana Hotel after Earthquake, New Zealand by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/151 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

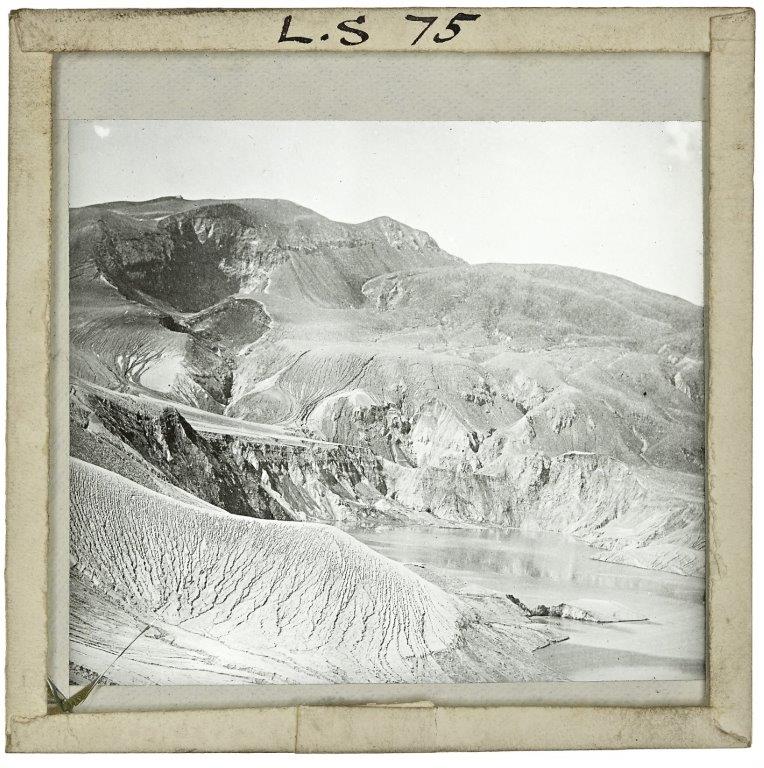

Mount Tarewera after Eruption, New Zealand by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/152 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

Christchurch Cathedral and the 2011 Earthquake

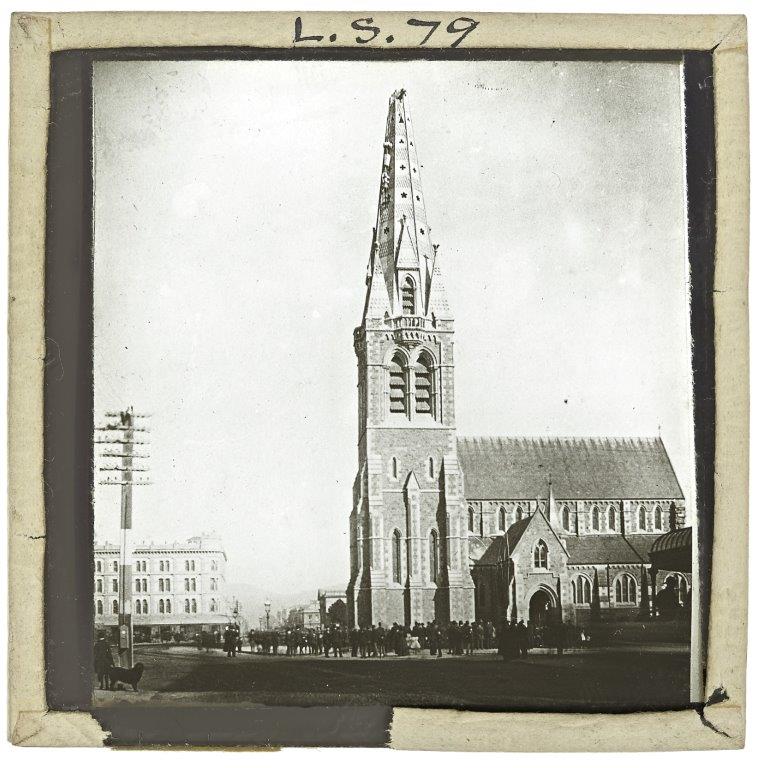

When I viewed Whinfield’s slide images the first time, besides the images of Wellington and Lake Tarawera, was Christchurch Cathedral without its spire, but from over 100 years ago!

View of Christchurch from the air, New Zealand February 2013 © Anthony Roach

At 12.51pm on 22 February 2011, a magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck the city of Christchurch, as reported by the New Zealand Defence Force. 185 people died and thousands were injured – the second worst natural disaster in New Zealand’s history. Buildings collapsed or were severely damaged and critical infrastructure including water, roads, sewerage, power and telecommunications went down. This was followed by hundreds of aftershocks which led to further misery for the people of Christchurch whose resilience was tested again and again. Here is a before and after set of images which illustrate the devastation throughout the city.

Christchurch Cathedral, New Zealand, After Earthquake by A.H. Whinfield Finding No: 832 BA16072/155 courtesy of The Diocesan Church Trust

Large parts of the Christchurch City centre were declared a Red Zone and cordoned off due to the infrastructure being unsafe or habitable. During a Red Zone tour I saw the shear devastation that the February earthquake had caused and the sad remains of the much beloved Cathedral whose spire had gone completely. With the Canterbury region so susceptible to earthquakes it shouldn’t be a surprise that the Cathedral has lost its spire more than once.

Whinfield’s slide shows the spire having toppled during the Earthquake of 1888, as reported by Lost Christchurch, a website devoted to Christchurch’s history. He writes in his lecture notes that: “Though some distance away the Cathedral of Christ Church suffered from the earthquake, and you will see that the top of the spire has broken away…”

Building remains of Christchurch Cathedral in 2013 © Anthony Roach

Whinfield was remarkable for journeying around the globe during the late 19th century when travel was incredibly hard. It remains a mystery how far he travelled (only a single letter exists from 1892 from his colleague W.A. Brooke concerning his slides and the text to accompany his next public lecture) but he returned home in 1897. His glass slides can be used by researchers to learn more about the world during the 1880’s and demonstrate how archive collections like these are internationally significant for the incredible insights they offer into people, places and world events.

You can view Whinfield’s slides for yourself via the Lucerna website.

A.H. Whinfield glass slide cabinet © WAAS

Further Sources:

‘Missing’ – A journey through the Arthur Henry Whinfield magic lantern slide collection by REDHAWK LOGISTICA

Post a Comment