Body on the Bromyard Line 4 – The Research

- 17th May 2024

This is the fourth in a series of five posts exploring the story behind the human skeleton found buried within an embankment of the Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster railway line in 2021, close to Riverlands Farm in Leigh, to the west of Worcester.

Over this mini-series we explore the discovery, and what we have learnt through the archaeological excavation, scientific analyses and documentary research. Built in the 1860s, the line eventually closed in the 1960s, and by 2021 all that remained was the earthwork of the former embankment that took a narrow lane up and over the railway. Hidden within the bank was a single human skeleton (see Blog 1: The Discovery).

Initial archaeological and scientific analyses support the theory that this body could be someone who had died whilst working on the railway line. Local researcher Dave Bonnick therefore examined the archives here at The Hive in Worcestershire, and went down to Kew, to The National Archive (TNA), to view the railway archives there. The aim was to find out more information about the construction of the line, and the men who built it.

The Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster (WB&L) Railway received Royal Assent on the 1st August 1861. The men, known as navvies, were reported as having started work, finally, by 1st August 1864. Construction commenced at Bransford and the section between Bransford and Bromyard was completed by 1871. Archival research suggests that the stretch between Leigh and Bransford was likely completed by the late spring of 1866.

The Broad Dingle viaduct, just north of Alfrick, still stands on the parish boundary with Lulsley as a testament to the hard work of the navvies. Our man may have been involved in the construction in the months before his death.

It is harder to pin the date of the embankment down beyond the period August 1864 – May 1866. The line appears to have been constructed in several places at once, rather than starting in Bransford and working towards Bromyard in a linear fashion. There are references in the letters and accounts to progress in various places throughout 1864, ‘65 and ‘66. On the 30th September 1865, for example, there was a note that the three miles of construction from Bransford were in a “forward state”. This suggests that the navvies were still in the area of Leigh over a year after construction reportedly started at Bransford.

Around 350 men worked the line at its peak. On the 23rd November 1865 it was recorded:

“….and have since the 25th of October last (as requested) increased my staff by the addition of 66 men and 6 horses making a staff of about 350 men and 30 horses. ”

By 12th January 1866, Mr W B Lewis reported that he had gone over the line and that he found the works were not progressing satisfactorily. The number of men had been greatly reduced, the remainder had not been paid their wages and would if something was not done be starved. He also reported that six houses had been seized by the sheriff of Herefordshire for a debt. This seems to be typical of the national situation. Contractors were often incompetent or unscrupulous, and there are numerous records nationally of navvies regularly half-starved or in debt.

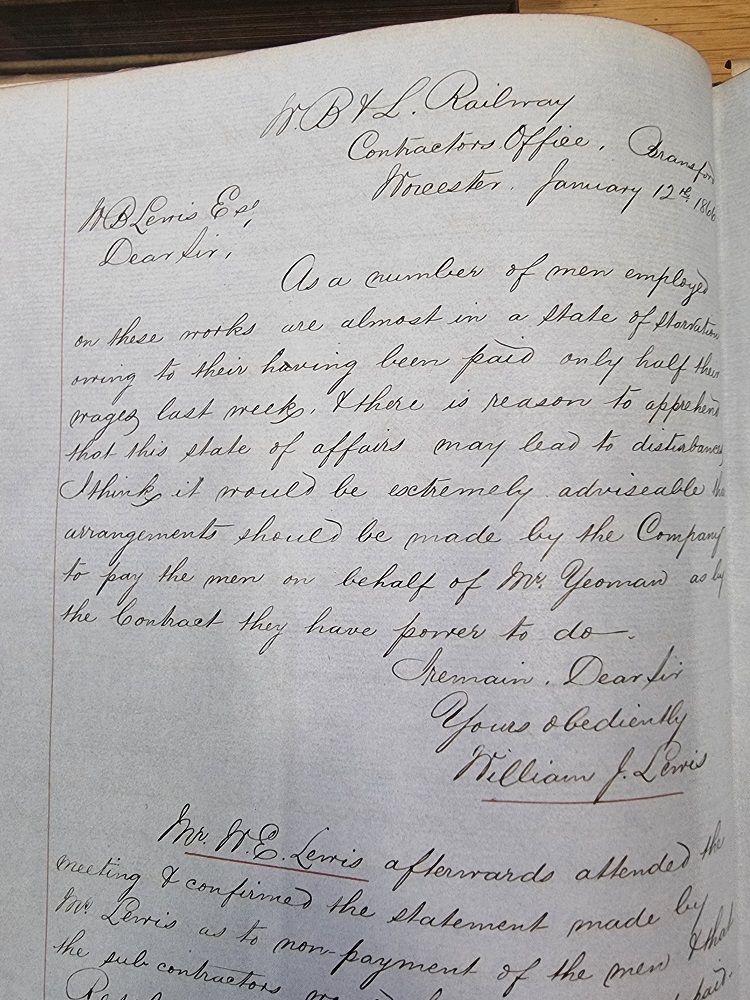

Extract from the letters at The National Archives.

“Dear Sir, As a number of men employed on these works are almost in a state of starvation owning to their having been paid only half their wages last week. There is reason to apprehend that this state of affairs may lead to disturbances. I think it would be extremely advisable that arrangements should be made by the Company to pay the men on behalf of Mr Yeoman as by the contract they have power to do. I remain dear sir, yours obediently William J Lewis.”

The history of the ‘navvies’ or ‘navigators’ dates to the 1760s and the building of the nation’s canals. Initially, canal building involved employing local men, as had been normal practice on other large construction projects, but this work quickly evolved to become a ‘profession’ with many thousands of men travelling the country from one contract to another, often with their families in tow. These men became known as navvies. Between 1760 and 1840 over 2000 miles of canals, including bridges, tunnels and locks were constructed, employing many thousands of men. From the early 19th century the navvies moved into railway construction, building around 20,000 miles of line by 1900.

Navvies came from across Britain and Ireland, and occasionally abroad. They were well known for the astonishing amount of work they could accomplish each day, but it was also a dangerous and unpleasant life. Consequently, they were well paid compared to other manual jobs. Partially this was due to the unpleasantness of the work, but also partially due to the fact that navvies were not tied to a contract. They could simply up and leave if another contractor was paying better wages.

It was dangerous and arduous work, and a challenging life, living in poorly constructed tents or huts alongside the bridges, tunnels and cuttings that they were building. Settlements were often without sanitation or clean water. Sometimes 15-20 men were recorded sharing one hut. Diseases like cholera were rife, and it must have been miserable in the winter to live in a tent, or a hut built of turf.

According to the National Railway Museum website, the death rate among the workers was higher than that of the soldiers who fought at the battle of Waterloo. Railway workers were being killed at the rate of nearly 500 a year by the 1880s and 1890s. There are anecdotal stories about workers dying on the job and being dumped alongside where they were working. Elizabeth Garnett, a missionary and founder of the Navvy Mission Society, recorded a navvy saying to her: “I went round Eston. We call it the slaughterhouse, you know, because every day nearly there’s an accident, and nigh every week, at the farthest, a death”.

There are no records of the number of injuries and deaths on many lines, but there are many contemporary accounts about the lack of provision when catastrophe occurred. In 1851 an author, John Francis, wrote “Robert Stephenson infused into the workmen so much of his own energy that when either of their companions were killed by their side, they merely threw the body out of sight and forgot his death in their own exertions”.

There were sadly no accounts in the local newspapers or railway archives that shed any light on who was living and working on the railway line between Worcester and Bromyard, but evidence from across the nation builds a pretty grim picture of navvy life, and death. Was this how our man finished his days? Find out future plans and research in the last instalment of this mini-series: Body on the Bromyard Line Blog 5

Information in this post is taken from:

Burton, A. 2012. History’s most dangerous jobs: Navvies. The History Press ISBN 978-0-7524-7961-3

Coleman, T. 1963. The railway navvies: A history of the men who made the railways. Hutchinson Press.

Railway Museum. 2018. Navvies – workers who built railways

Smiles, S. 1857. The life of George Stephenson. 2006 reprint Hesperides Press.

Smith, W. 1998 The Bromyard Branch: From Worcester to Leominster.

TNA 763/1. Letters to the board of the Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster Railway1864-1866. Accession number 763/1 The National Archive, Kew.

Post a Comment