Body on the Bromyard Line 5 – The radiocarbon bombshell!

- 18th May 2024

This is the fifth and last in a series of five posts exploring the story behind the human skeleton found buried within an embankment of the Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster railway line in 2021, close to Riverlands Farm in Leigh, to the west of Worcester. Over this mini-series we explore the discovery, and what we have learnt through the archaeological excavation, scientific analyses and documentary research. Built in the 1860s, the line eventually closed in the 1960s, and by 2021 all that remained was the earthwork of the former embankment that took a narrow lane up and over the railway. Hidden within the bank was a single human skeleton (see Blog1: The Discovery).

Every good mystery needs a sudden plot twist, doesn’t it? The story of our body certainly gave us one. Given the disturbed state in which he was found, we wanted to make sure that our man was buried in the 1860s. We’d always known that there was a possibility that the bottom layer of the embankment would pre-date the 1860s, but we considered that unlikely.

Over the last few decades, a wide range of scientific techniques have been developed that can date artefacts and soils/layers, providing confirmation that stratigraphic relationships are valid, or dating archaeology that couldn’t otherwise be assigned an age. Radiocarbon dating is probably the best known of these techniques.

Radiocarbon dating (often abbreviated to C-14 dating) is a method that calculates the amount of carbon 14 (a radioactive isotope of carbon) found in organic remains like charcoal or bones. Animals and plants absorb C-14 into their bodies as they breathe it in. C-14 decays into nitrogen (N-14) at a known rate, which can be measured. Throughout life, an animal replaces the C-14 in their bodies, but as soon as they die this replenishment stops. There is only decay. Scientists can measure the amount of C-14 relative to N-14 in a sample and work out how much C-14 there must have been to start with and how long it has been decaying. This will tell them when the animal or plant died. As the amount of C-14 in the atmosphere varies over time, scientists refine the initial date to reflect the atmospheric carbon around the time of death. We know how much C-14 there was in the atmosphere of earlier periods through measuring the amount stored in ice cores. This process of refining the date based on known atmospheric carbon is called ‘calibration’.

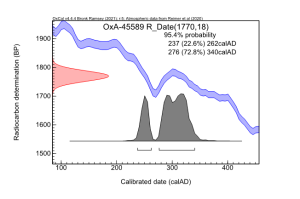

We sent a sample from our skeleton to the radiocarbon laboratory at Glasgow University (SUERC) for analysis. Much to everyone’s surprise, the results returned a date of 3rd or early 4th century AD – the ROMAN period! Consultation with SUERC and with Historic England’s science advisor indicated that the result was likely genuine and not a product of a contaminated sample. However, to be sure that there wasn’t a mistake, a second sample was taken and sent to the Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). This sample returned the same date.

The calibrated radiocarbon result from Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU)

Once we had got over the surprise, and initial disappointment, we realised that this could be an interesting piece in a different jigsaw puzzle. We know from the scientific analysis that our man did not grow up in Worcestershire, and that he was likely not a wealthy or high-status person. Perhaps, then he might be able to contribute to our understanding of how ordinary people moved around Britain and the Roman Empire during the Roman period?

There is a general understanding that the Roman Empire brought with it an unprecedented level of people-movement. This is evidenced through contemporary written accounts and inferred by the archaeological evidence of trade in the distribution of pottery, coins and foodstuff. It is also found in the people themselves, by isotopic and genetic analyses of people buried in cemeteries across the Empire. However, this genetic/isotopic research has largely focussed on military, high-status and slave cemeteries. We know that they moved around the Roman Empire. But what of ordinary people? Did they have opportunities or need to travel long distances? Was the mobility of the average farmer’s son or daughter any greater than it had been in Iron Age Britain?

Researchers at the University of York and Cardiff University are working on a three-year project investigating population movements around Roman Britain. The UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) has awarded £1.49m for The Roman Britannia: Mobility and Society project. This will be the largest combined archaeological, isotopic and ancient DNA study into a Roman population ever undertaken. This project will be focused on a wide range of people and sites, investigating not just movement into Britain, but also movement of people within the country. The Roman Britannia project is using data from cemetery sites to look at whole populations, so they won’t include data from our single individual. However, once completed their project will create a large dataset that we can compare our body’s results to.

We are also waiting on detailed DNA analysis. The Crick Institute was awarded a £1.7m Wellcome Trust grant to unearth new insights into human evolution and disease. The research is understanding how the genetics of people in Britain changed over thousands of years. By identifying the genetic changes that took place and matching these changes against key moments in history, the study will uncover new insights into the evolution of humans and disease. Over five years, researchers are sequencing the whole-genomes of several thousand ancient British people, using skeletal samples from the last 5,000 years. Our body will now be a part of that project. The initial results are back, confirming that his DNA has been successfully sequenced, and that he is biologically male.

Whether we will receive further insights into this person’s origins remains to be seen, but the data that we have gathered comes at an exciting point in the scientific research into Roman Britain. The data about each and every person, whether an isolated individual or from a large group, is building up a picture of how our ancestors lived and died in the Roman period. This result can add to growing body of evidence that shows people were highly mobile within Britain and across the Roman Empire.

Information in this post-series is taken from:

Burton, A. 2012. History’s most dangerous jobs: Navvies. The History Press ISBN 978-0-7524-7961-3

Coleman, T. 1963. The railway navvies: A history of the men who made the railways. Hutchinson Press.

Cornah, T. Vaughan, T 2022. Archaeological watching brief at River Lands Farm, Teme Lane, Leigh, Worcestershire. Worcestershire Archaeology unpublished report.

Moore. J. Montgomery, J. 2024. Specialist Report: Multi-isotope study of a 19th century skeleton recovered in Leigh, Worcestershire. AIPRL Report No. 179. Department of Archaeology, Durham University. Unpublished report.

Railway Museum. 2018. https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/navvies-workers-who-built-railways

Smiles, S. 1857. The life of George Stephenson. 2006 reprint Hesperides Press.

Smith, W. 1998 The Bromyard Branch: From Worcester to Leominster.

TNA 763/1. Letters to the board of the Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster Railway1864-1866. Accession number 763/1 The National Archive, Kew.

Western, G. 2023. Osteological Analysis of the Human Remains from River Lands Farm, Leigh, Worcestershire. Ossafreelance report no.OA1125

Post a Comment