From petty crimes to ‘poor man’s bread’ – the surprising value of watercress revealed in the Worcestershire Petty Sessions

- 8th July 2024

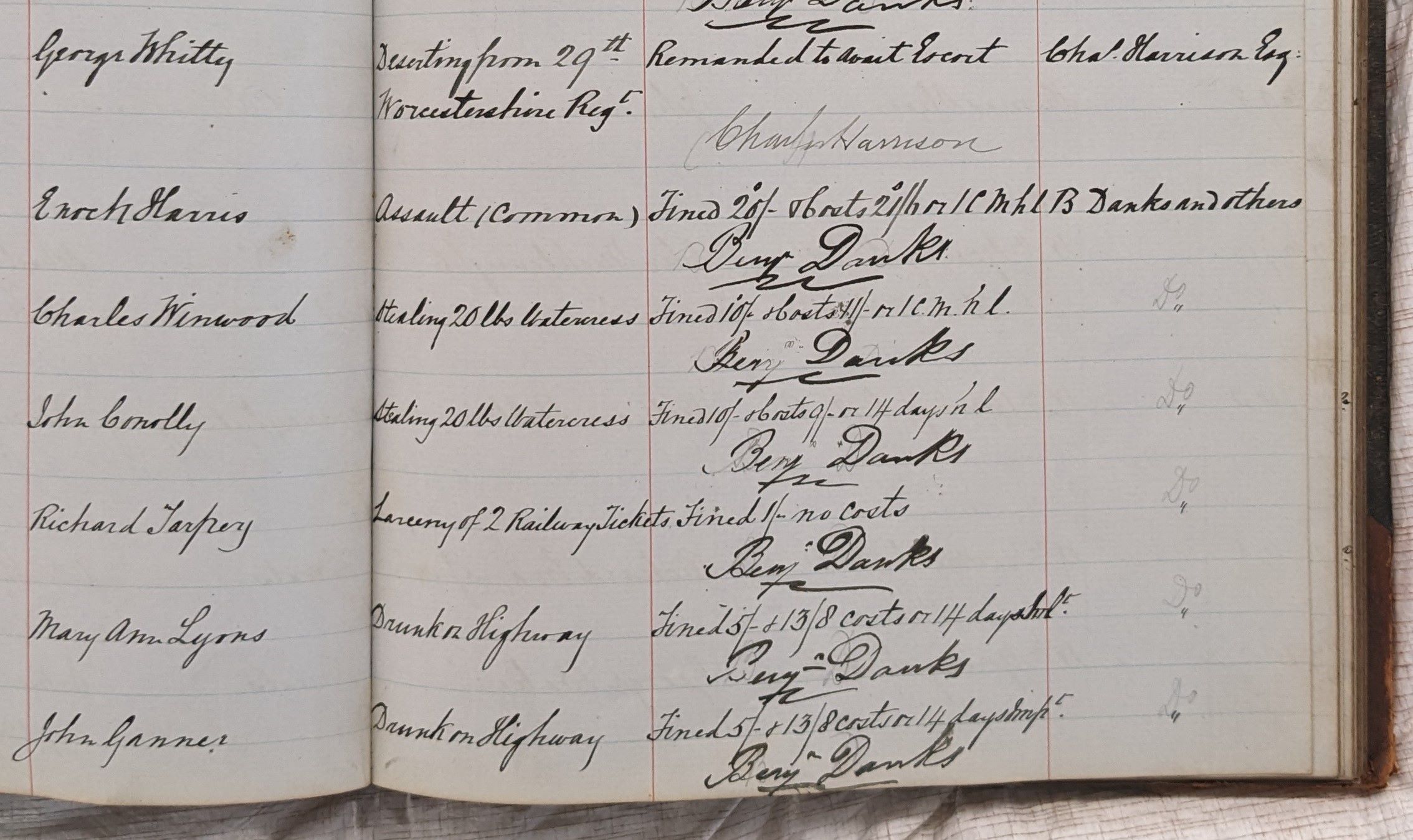

Stealing of watercress recorded in the Stourport on Severn-Petty sessions at Ref 499.1 BA8470/28 p.73

Petty Sessions and Magistrates Court records are amongst some of the huge variety of public records held with Worcestershire Archives on behalf of Worcestershire County Council as part of The Public Records Act. The Public Records act requires certain public bodies to transfer records of historical value for permanent preservation to their archive services appointed as ‘places of deposit.’ As part of New Burdens funding, we are undertaking the review and cataloguing of both Petty Sessions and Magistrates Court records, and Petty Sessions are the focus of today’s blog.

Since Medieval times until 1971, the hierarchy of the lower courts consisted of Petty Sessions being at the base of a structure, followed by Quarter Sessions and then the Assize courts, where the more serious of criminal trials took place at least twice a year. As the name suggests Petty Sessions dealt with petty crimes, which included drunkenness, stealing, larceny and bastardy. These, mostly minor, offences were dealt with by unpaid, non-professional judges known as Justices of the Peace. Also known as magistrates, these Justices came under greater scrutiny following a Royal Commission by the UK Parliament to improve regulation which led to the Justices of the Peace Act 1949.

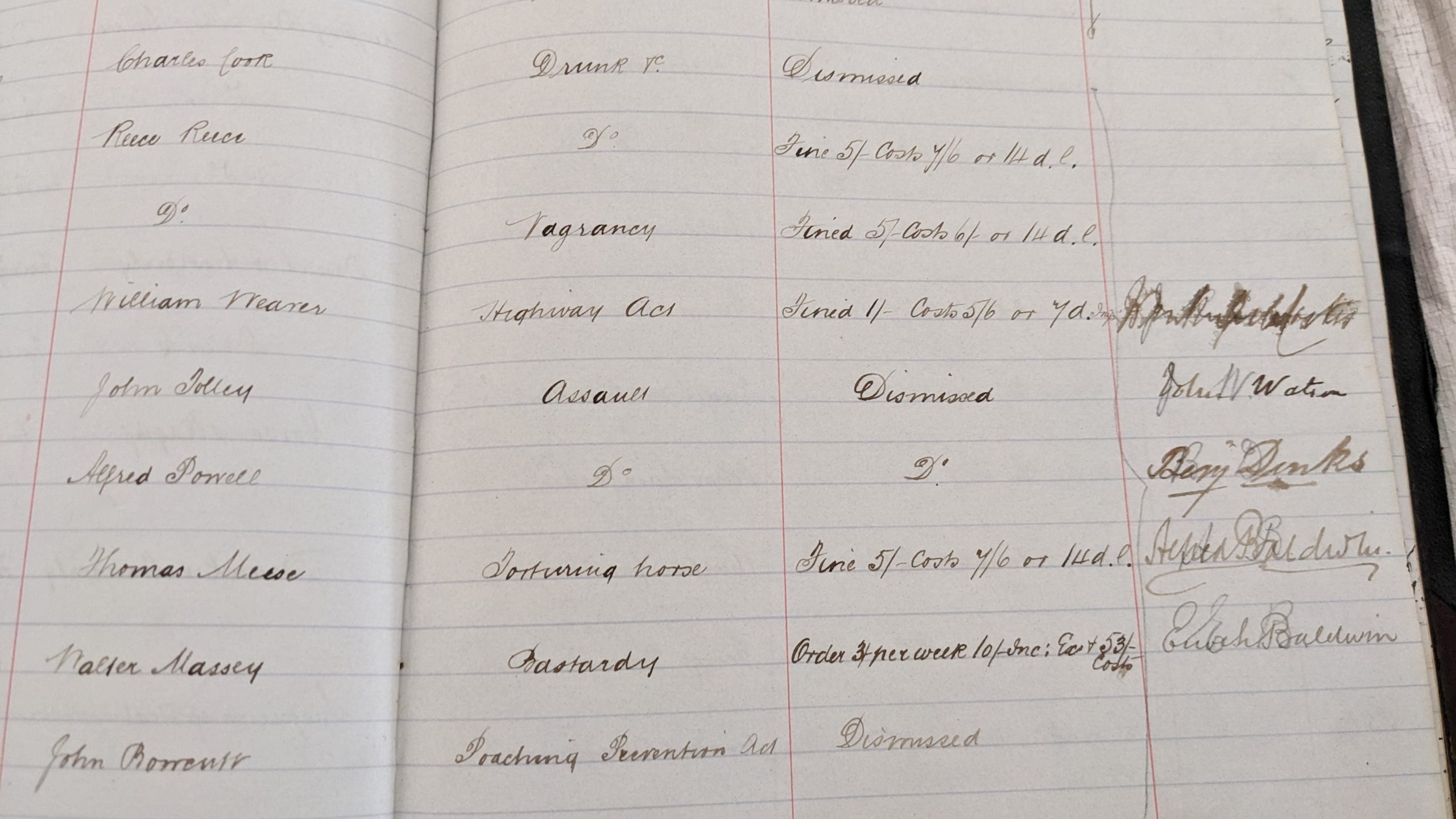

Stourport-on-Severn Petty Sessions Register at Finding No: 499:1 BA8470/28 p.22 dated 7th May 1889 featuring petty crimes including drunkenness, vagrancy, assault, bastardy, and torture of horse.

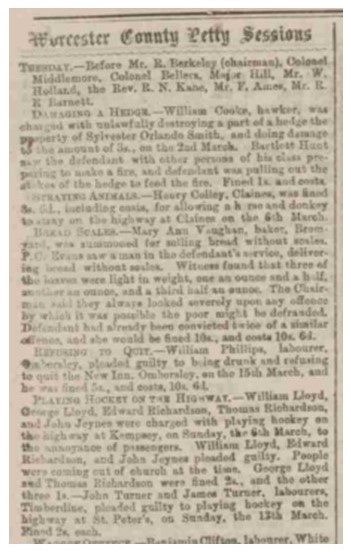

As we can see in Stourport and Worcester Petty Sessions records from the 1880’s, whilst stealing featured heavily in the records, assault and cruelty to animals was also not tolerated. Other crimes which led to fines in the Worcester and Stourport Petty Sessions were obstructions on the Highway and, as shown from The Worcestershire Chronicle on the 26th March 1887, a Henry Colley was fined 3s. 6d for allowing a horse and donkey to straying onto the highway. Similarly, George and Henry Lloyd and Edward and Thomas Richardson were fined 7s. for playing hockey on the Highway on Sunday 6th March, whilst parishioners were coming out of the church.

Worcester Petty Sessions reported in The Worcestershire Chronicle, 26th March 1887 referring to fines for obstructions to the highway.

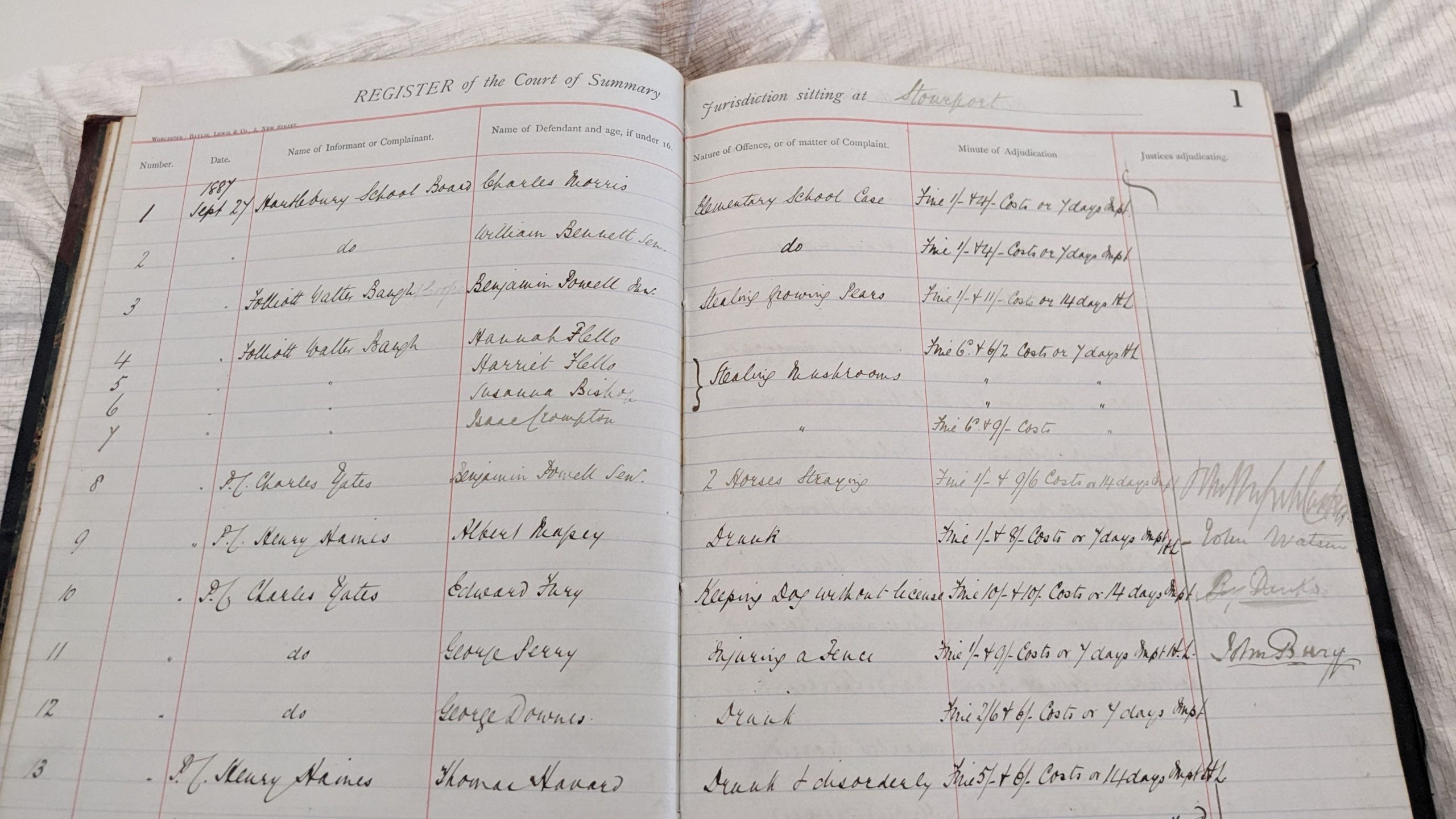

Stourport-on-Severn Petty Sessions at Finding No 499.1 BA8470.28 p.1 dated 27th September which makes references to stealing pears and mushrooms

However, amongst the charges for assault and stealing, with common items being pears, potatoes and coal, a surprising number of cases were to do with watercress theft – so much so that there is one case every few pages during the 1880’s records. This curious fact was reported by Murray Andrews and Francesca Llewellyn in the Spring 2023 Edition of the Worcestershire Recorder, were they noted that between 1850 and 1899 no fewer than 254 people were prosecuted at the Worcestershire Petty Sessions in 188 cases of watercress theft.

Image: Joseph Barnsley listed alongside Thomas Shuter in the Worcester Petty Sessions on the 22nd March 1887 for the stealing of watercress. He is mentioned multiple times in the records.

Amongst the crimes listed in the Worcester Petty Sessions on the 22nd March 1887 is the most notable watercress stealer of them all – one Joseph Barnsley, and his accomplice, Thomas Shuter for ‘stealing watercress growing in a field in Hallow’. Barnsley was also convicted for assault, with the punishment being hard labour and fines of 4s 6d each. ‘Watercress Joe’, as he became known, supplemented his income as a labourer and street hawker ‘with an underworld career in a ‘regular gang of thieves’’. Barnsley and Shuter, along with Abraham Golden, Albert Hedge and John Williams are all mentioned in the Recorder as being in and out of jail for pickpocketing, assault and watercress theft, with the largest amount being 40Ibs from a farm in Malvern. Barnsley is also mentioned later in 1887, on the 7th May, at the Stourport Petty Sessions for the same crime with John Williams. Both were sent straight to prison and hard labour.

An article describing the unique properties of watercress in The Berrow’s Worcester Journal article dated 13th August 1887

This begs the question, if watercress was so often stolen, what was it about the plant that made it such an important commodity in the late 19th century? The Berrow’s Worcester Journal of 13th August 1887 describes the unique properties of watercress which made it such a valuable food, particularly for the poorest people in society. It states that where watercress is grown in the right conditions in a stream, it absorbs five times the amount of iron of any other plant and is a great ‘blood purifier’, containing properties of garlic, sulphur, iodine and phosphates. The article also highlights how given the right conditions: ‘watercress is easily grown, for in favourable surroundings, a plant can be cut into pieces and thrown into the water, with the result that each of the severed portions produces a complete plant’.

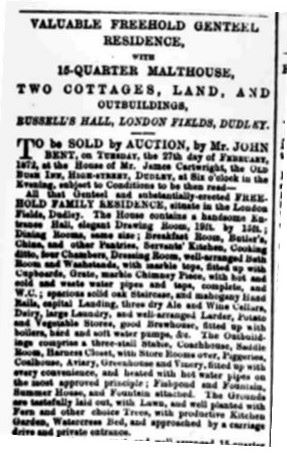

Property in Russell’s Hall, London Fields, Dudley that makes reference to a watercress bed taken from The Stourbridge Observer, 17th February 1872

This would have certainly been helpful to those people who had access to a stream or watercress bed, either privately or on common land, so that it could have been easily cultivated. Indeed, the sale of property at the end of the 19th century frequently refers to watercress beds, as unique selling points alongside orchards, greenhouses, allotments, piggeries and outbuildings. An example from the Stourbridge Observer advertising a ‘Valuable Freehold Genteel Residence, with 16-Quarter Malthouse, Two Cottages, Land and Outbuildings’ at Russell’s Hall, London Fields, Dudley describes how ‘the grounds are tastefully laid out, with Fern and other choice Trees, with productive Kitchen Garden’ and Watercress Bed.

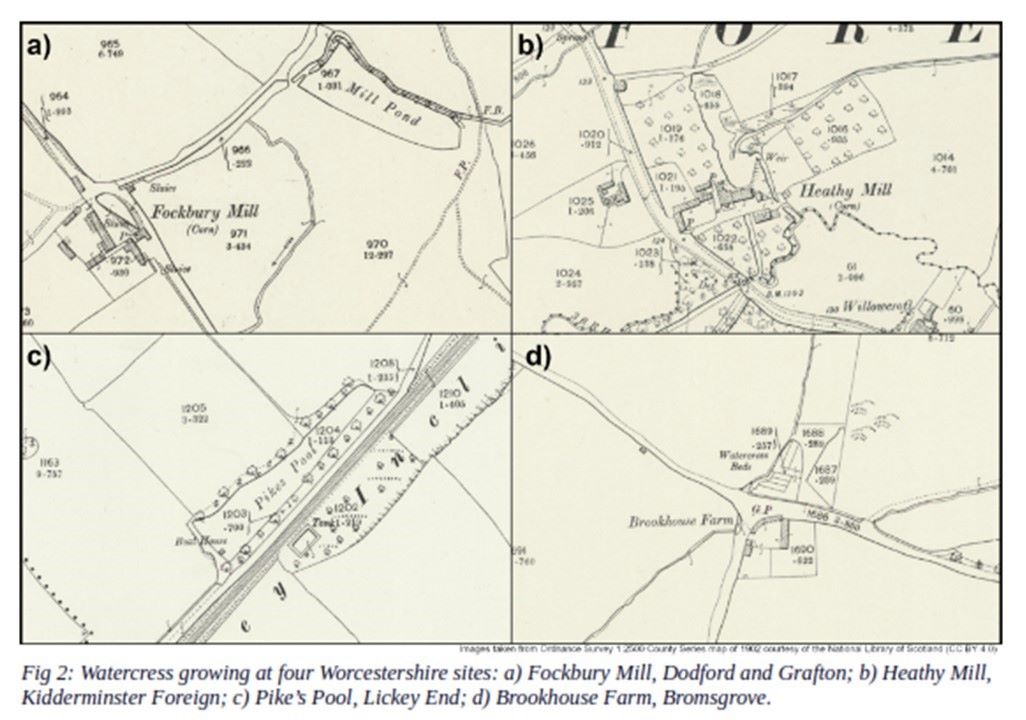

Whilst people did grow watercress within the vicinity of their properties, planting beds for watercress were typically lain in streams, brooks, or ponds. Through a variety of cartographic, documentary and archaeological sources, Andrews and Llewellyn have found examples of watercress growing at Fockbury Mill, Dodford and Grafton, Heathy Mill, Kidderminster Foreign, Pike’s Pool, Lickey End and Brookhouse Farm, Bromsgrove.

Examples of Watercress growing at a) Fockbury Mill, Dodford and Grafton, b) Heathy Mill, Kidderminster Foreign, c) Pike’s Pool, Lickey End and d) Brookhouse Farm, Bromsgrove reproduced from Andrews and Llewellyn, Worcestershire Recorder, Spring 2023

Watercress was grown commercially across England in the 19th century, starting in Kent and spreading across the south of the country from the 1820’s. This has been largely forgotten about, as well as its nickname ‘poor man’s bread’. It was eaten in large quantities (some 32,000 bunches a day) by England’s poorest in urban areas of Worcestershire such as Bromsgrove, Kidderminster, Droitwich and Worcester, where watercress could easily be sent in a day by horse and cart from where it was grown and picked. Those in urban areas were ripe for exploitation by gangs such as Joseph Barnsley’s. ‘Watercress hawkers’ bought and sold small quantities of low-grade produce in the streets and door-to-door.Some of this material was also stolen and traded in the slum areas of Worcester. Meanwhile, the poorest in the countryside were also fined and/or imprisoned for foraging for watercress in sheer desperation, due to starvation. This was described by Henry Grove and George Taylor who pleaded to the court, having stolen 20lbs of cress from Hartlebury, that ‘their children were ‘clamming’ and they were tempted to take the watercress to get them some food’.

It was also the poorest who were the first to suffer the consequences of poor-quality produce, such as watercress grown or refreshed prior to sale in contaminated water. There are numerous stories of untreated sewage entering our waterways and campaigns to improve rivers such as the Wye. Some researchers have suggested that certain typhoid outbreaks in 19th century London were partly caused by watercress hawkers vending sewage-grown produce or refreshing their wares in contaminated water. In Worcester, one victim of the city’s 1849 cholera outbreak was ‘a poor woman named Price, a vender of water-cress living in Hound’s-lane’ which suggests watercress was easily susceptible to contamination.

An article from The Worcestershire Chronicle, dated 3rd February 1877 entitled ‘Poisonous plants mistakenly gathered’ highlighting how poisonous plants were gathered in place of watercress

Furthermore, watercress (just like mushrooms) could easily be mistaken by the uneducated for poisonous plants. The fatal consequences of this were reported by Edwin Lees (founder member of Worcestershire Natural History Society, later Worcestershire Naturalists Club). Lees states in the Worcestershire Chronicle of February 1877 that ‘This is a seasonable warning, as the cry of “Spring water-cresses” will soon be made, and careless gatherers may pick the wrong foliage, which I have known done.’ He says in particular that the common shepherd’s purse looks like a cruciferous plant (the group that includes mustard and watercresses) but is in fact poisonous, along with the marshwort, and that ‘most umbelliferous plants are suspicious and some very poisonous’. It is therefore entirely possible that some sellers caused their own demise and those of their fellow customers, along with the dangers of carelessness or – just as likely – desperation, when foraging for watercress to curb their hunger.

| https://www.explorethepast.co.uk/2024/05/the-new-burdens-project/

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/laworder/court/overview/jps/ |

Post a Comment